|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 45 Page 13 |

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

|

It's Elementary

Anthony Element.

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

|

|

|

There Ought to Be Another Word.

This edition I’m going to talk about something I’m pretty sure every

reader has done, is

Of course, I’m talking about retirement - What did you think was coming at ya?

‘Retire’ – it’s such an innocent sounding word, like something you

might do to your 4 Wheel Drive before setting off around Australia.

But it’s not innocent. It’s bloody sneaky in fact. It’s right there

before you know it, and no matter how prepared you think you are,

you haven’t got a clue what it’s really about.

People say that when you retire you have time to do the stuff you’ve always wanted to do. Yeah, right. But now you’re too old to be able to do it. And even if you do try doing it, people will think you’re just weird.

Fun fact: research has proven conclusively that the average life expectancy of retirees is much lower that of people going to high school. So, if you want to live longer go back to school!!

Actually retiring really sucks.

Turns out you just sit around waiting. And what you’re waiting for sucks even more than the waiting.

When I mentioned this to my mate Harvey, he didn’t speak for a bit. He just stared out the garage door at the horizon in that way he has, waiting for Jerry Garcia to finish a solo on the stereo, at a volume that had dogs howling in Toowoomba.

And we live in Brisbane.

He picked up a gleaming spanner, leaned over his Harley and made a microscopic adjustment to the carburettor. Then he wiped the spanner and put it back in its place on this immense shadow board he has.

He stood back, squinted, and then reached forward and adjusted the spanner so it was hanging perfectly vertically. Did I ever mention that I sometimes think Harvey is just a tad obsessive?

Anyway, he goes to his forty year old Kelvinator, which, by the way, runs quieter than my watch - and my watch is digital – and pulled out a can. He cracked it, took a huge slug, belched expansively and then murmured, “Retirement? If I’d known what retire bloody meant I’d never’ve gone near it.”

“Did I ever show you the flow chart I made, trying to figure out how to retire?”

“No,” I replied, surprised. I’d never have taken Harvey for the flowcharting type.

“Blood oath.” He reached up to his top shelf and pulled down a file, flipped it open and gave me a squiz.

“Now,” he said, “I’ve got nothing against cracking a tinny or six, but you gotta have something to have a crack at in between getting up and cracking one… if you get what I mean.”

I decided right there that old Harve had nailed the sucker. You’ve got to have a challenge in your life. Of course, there’ll come a time when just tucking your shirt in will be a challenge, but that’s usually a fair way off when we retire.

“Did you know,” Harvey said, interrupting my brilliant train of thought, “that an astonishing number of retirees get depressed?”

“I didn’t,” I replied, “but I’m not surprised. Getting old is, in itself, bloody depressing.”

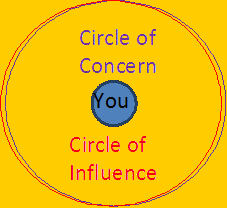

“Yeah, but that’s not what I meant. It’s all to do with your Circles of Influence and your Circles of Concern.” Every so often, Harvey really surprises me. It can be downright scary.

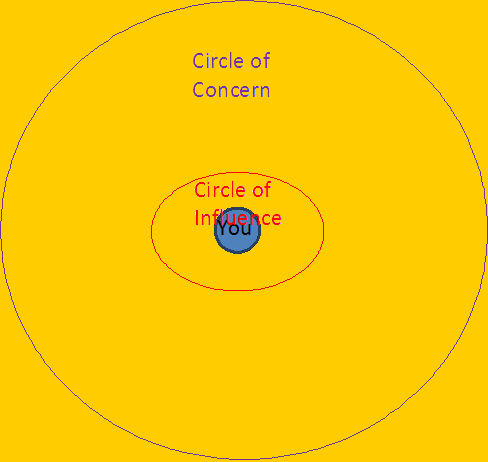

Harvey pulled a sheet of paper from a drawer under his immaculate work bench and drew a big dot in the middle. “Imagine,” he said, “That’s you.”

“I suppose,” I replied, “That if I were to squint…”

“Don’t be a smart arse,” Harvey said, as he drew a circle with the dot in the middle, using a blue pen. “Now, imagine that inside that circle are all the things you worry about. That’s your Circle of Concern.”

“Okay,” I said, cautiously.

Harvey then drew another circle about the same size as the first one, but in red. “Inside this circle are all the things you can actually do something about. This one is called your Circle of Influence.”

Now the diagram looked like this:

I stared at the diagram. Yep, I’d been there. “Okay, I said. “I’ve got that.”

“Right,” Harvey said. “Now let’s look at what happens when you rebloodytire.”

“One day you’re maybe a boss with lots of contacts and a fair bit of power and influence. People listen to you. Then Bam! The gold watch. Now, you’re the boss of no one, nobody listens to you, you don’t have a title and pretty soon all your old contacts are too busy to talk to you.”

“Well, that’s not good,” I opined.

“Not good at all,” Harvey said, vehemently. “But it gets worse. Now you’ve got this time on your hands. You start to read more. You listen to talk back radio more. You’ve got time to read the whole paper. And you discover something monumental.”

What’s that,” I asked.

“That,” Harvey said, solemnly, “the world is entirely R.S.”

“Really?”

“Really. So suddenly your Circle of Concern gets huge. And guess what.”

“What?”

“You can’t do a bloody thing about any of it.” Harvey quickly drew a

new diagram:

“So here you are, with all this time on your hands. And you’re discovering all this terrible stuff you never had time to worry about before.”

“Like what?”

“Like Global Warming, Iran might build a nuclear bomb, Justin Beiber’s got issues about driving, Rupert Murdock wants to own the ABC, and every day twenty six million plastic bags get put in the ocean. And that’s just for starters.” “And here’s the thing. You can’t do a thing about any of it. Actually, you never could, but now everybody and their brown dog make sure you know it.”

Harvey grabbed a couple more tinnies from the fridge and passed one over to me. As he cracked his, he said, “Now you know why so many retirees get seriously depressed. So you just watch yourself, alright?”

And so, boys and girls, here are Harvey’s tricks for surviving that bit of your life after you quit working for someone else:

· Find yourself something challenging to do; and · Don’t sweat over what you can’t do anything about.

Oh, and it helps to have an old Kelvinator full of the amber fluid.

But I still think there should be another name for it – that bit of your life, I mean, after all, I’m quite happy for beer to be called amber fluid.

Anthony V Element OAM Observation Point (Founder and Editor)

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is a true story of 20 year old Bruce Carr.

Bruce was a fighter pilot who was shot down behind enemy lines in World War Two.

The dead chicken was starting to smell. After carrying it for several days, 20-year-old Bruce Carr still hadn't decided how to cook it without the Germans catching him. But as hungry as he was, he couldn't bring himself to eat it raw. In his mind, no meat was better than raw chicken meat, so he threw it away.

Resigning himself to what appeared to be his unavoidable fate, he turned in the direction of the nearest German airfield. Even POW's get to eat sometimes. And aren't they constantly dodging from tree to tree, ditch to culvert? He was exhausted!

He was tired of trying to find cover where there was none. Carr hadn't realized that Czechoslovakian forests had no underbrush until, at the edge of the farm field, he struggled out of his parachute and dragged it into the woods.

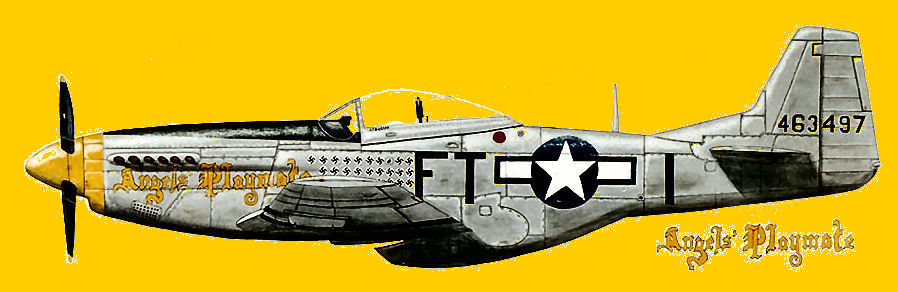

During the times he had been screaming along at treetop level in his P-51 'Angels Playmate' the forests and fields had been nothing more than a green blur behind the Messerchmitts, Focke-Wulfs, trains and trucks he had in his sights. He never expected to find himself a pedestrian far behind enemy lines.

|

|

|

|

The instant antiaircraft shrapnel ripped into the engine, he knew he was in trouble. Serious trouble. Clouds of coolant steam hissing through jagged holes in the cowling told Carr he was about to ride the silk elevator down to a long walk back to his squadron. A very long walk.

This had not been part of the mission plan. Several years before, when 18-year-old Bruce Carr enlisted in the Army, in no way could he have imagined himself taking a walking tour of rural Czechoslovakia with Germans everywhere around him. When he enlisted, all he could think about was flying fighters.

By the time he had

joined the military, Carr already knew how to fly. He had been

flying as

"In 1942, after I enlisted”; as Bruce Carr remembers it, "we went to meet our instructors. I was the last cadet left in the assignment room and was nervous. Then the door opened and out stepped the man who was to be my military flight instructor. It was Johnny Bruns! "We took a Stearman to an outlying field, doing aerobatics all the way; then he got out and soloed me. That was my first flight in the military.

"The guy I had in advanced training in the AT-6 had just graduated himself and didn't know a damned bit more than I did." Carr can't help but smile, as he remembers: "which meant neither one of us knew anything. Zilch!

"After three or four hours in the AT-6, they took me and a few others aside, told us we were going to fly P-40s and we left for Tipton, Georgia. We got to Tipton, and a lieutenant just back from North Africa kneeled on the P-40s wing, showed me where all the levers were, made sure I knew how everything worked, then said, 'If you can get it started .. . go flying,' just like that!

"I was 19 years old and thought I knew everything. I didn't know enough to be scared. They didn't tell us what to do. They just said: 'Go fly!' so I buzzed every cow in that part of the state. Nineteen years old and 1,100 horsepower, what did they expect? Then we went overseas."

|

|

|

|

By today's standards, Carr and that first contingent of pilots shipped to England were painfully short of experience. They had so little flight time that today; they would barely have their civilian pilot's license. Flight training eventually became more formal. But in those early days it had a hint of fatalistic Darwinism: if they learned fast enough to survive, they were ready to move on to the next step.

Including his 40 hours in the P-40 terrorizing Georgia , Carr had less than 160 hours flight time when he arrived in England .

His group in England was to be the pioneering group that would take the P-51 Mustang into combat, and he clearly remembers his introduction to the airplane.

"I thought I was an old P-40 pilot and the P-51B would be no big deal. But I was wrong. I was truly impressed with the airplane. I mean REALLY impressed! It flew like an airplane. I just flew the P-40, but in the P-51 I was part of the airplane. And it was part of me! There was a world of difference."

When he first arrived in England, the instructions just said, 'This is a P-51. Go fly it. Soon, we'll have to form a unit, so go fly.' A lot of English cows were buzzed.

"On my first long-range mission, we just kept climbing, and I'd never had an airplane above 10,000 feet before. Then we were at 30,000 feet with Angels Playmate, and I couldn't believe it! I'd gone to church as a kid, and I knew that's where the angels were and that's when I named my airplane Angels Playmate.'

"Then a bunch of Germans roared down through us, and my leader immediately dropped tanks and turned hard for home. But I'm not that smart. I'm 19 years old and this SOB shoots at me. And I'm not going to let him get away with it

"We went round and round. And I'm really mad because he shot at me. Childish emotions, in retrospect. He couldn't shake me, but I couldn't get on his tail to get any hits either.

"Before long, we're right down in the trees. I'm shooting, but I'm not hitting. I am, however, scaring the hell out of him. But I'm at least as excited as he is. Then I tell myself to calm down.

"We're roaring around within a few feet of the ground, and he pulls up to go over some trees, so I just pull the trigger and keep it down. The gun barrels burned out and one bullet, a tracer, came tumbling out and made a great huge arc. It came down and hit him on the left wing about where the aileron is. He pulled up, off came the canopy, and he jumped out, but too low for the chute to open and the airplane crashed. I didn't shoot him down, I scared him to death with one bullet hole in his left wing. My first victory wasn't a kill; it was more of a suicide."

The rest of his 14 victories were much more conclusive. Being a red-hot fighter pilot, however, was absolutely no use to him as he lay shivering in the Czechoslovakian forest. He knew he would die if he didn't get some food and shelter soon.

"I knew where the German field was because I'd flown over it, so I headed in that direction to surrender. I intended to walk in the main gate, but it was late afternoon and, for some reason, I had second thoughts and decided to wait in the woods until morning.

"While I was lying there, I saw a crew working on an FW 190 right at the edge of the woods. When they were done, I assumed, just like you assume in America, that the thing was all finished. The cowling's on. The engine has been run. The fuel truck has been there. It's ready to go. Maybe a dumb assumption for a young fellow, but I assumed so. So, I got in the airplane and spent the night all hunkered down in the cockpit. |

|

|

|

"Before dawn, it got light and I started studying the cockpit. I can't read German, so I couldn't decipher dials and I couldn't find the normal switches like there were in American airplanes. I kept looking, and on the right side was a smooth panel. Under this was a compartment with something I would classify as circuit breakers. They didn't look like ours, but they weren't regular switches either.

"I began to think that the Germans were probably no different from the Americans in that they would turn off all the switches when finished with the airplane. I had no earthly idea what those circuit breakers or switches did, but I reversed every one of them. If they were off, that would turn them on. When I did that, the gauges showed there was electricity on the airplane.

"I'd seen this metal T-handle on the right side of the cockpit that had a word on it that looked enough like 'starter' for me to think that's what it was. But when I pulled it, nothing happened. Nothing.

"But if pulling doesn't work . . . you push. And when I did, an inertia starter started winding up. I let it go for a while, then pulled on the handle and the engine started!"

The sun had yet to make it over the far trees and the air base was just waking up, getting ready to go to war. The FW 190 was one of many dispersed through-out the woods, and at that time of the morning, the sound of the engine must have been heard by many Germans not far away on the main base.

|

|

|

|

|

|

But even if they heard it, there was no reason for alarm. The last thing they expected was one of their fighters taxiing out with a weary Mustang pilot at the controls. Carr, however, wanted to take no chances.

"The taxiway came out of the woods and turned right towards where I knew the airfield was because I'd watched them land and take off while I was in the trees.

"On the left side of the taxiway, there was a shallow ditch and a space where there had been two hangars. The slabs were there, but the hangars were gone, and the area around them had been cleaned of all debris.

"I didn't want to go to the airfield, so I plowed down through the ditch and then the airplane started up the other side.

When the airplane started up . . . I shoved the throttle forward and took off right between where the two hangars had been."

At that point, Bruce Carr had no time to look around to see what effect the sight of a Focke-Wulf erupting from the trees had on the Germans. Undoubtedly, they were confused, but not unduly concerned. After all, it was probably just one of their maverick pilots doing something against the rules They didn't know it was one of OUR maverick pilots doing something against the rules.

Carr had problems more immediate than a bunch of confused Germans. He had just pulled off the perfect plane-jacking; but he knew nothing about the airplane, couldn't read the placards and had 200 miles of enemy territory to cross. At home, there would be hundreds of his friends and fellow warriors, all of whom were, at that moment, preparing their guns to shoot at airplanes marked with swastikas and crosses, airplanes identical to the one Bruce Carr was at that moment flying. But Carr wasn't thinking that far ahead.

First, he had to get there, and that meant learning how to fly the airplane. "There were two buttons behind the throttle and three buttons behind those two. I wasn't sure what to push, so I pushed one button and nothing happened I pushed the other and the gear started up. As soon as I felt it coming up and I cleared the fence at the edge of the German field, I took it down a little lower and headed for home.

"All I wanted to do was clear the ground by about six inches, and there was only one throttle position for me . . . full forward!

"As I headed for home, I pushed one of the other three buttons, and the flaps came part way down. I pushed the button next to it, and they came up again. So I knew how to get the flaps down. But that was all I knew.

"I can't make heads or tails out of any of the instruments. None. I can't even figure how to change the prop pitch. But I don't sweat that, because props are full forward when you shut down anyway and it was running fine."

This time, it was German cows that were buzzed, although, as he streaked across fields and through the trees only a few feet off the ground, that was not the intent. At something over 350 miles an hour below tree-top level, he was trying to be a difficult target as he crossed the lines. But he wasn't difficult enough.

"There was no doubt when I crossed the lines because every SOB and his brother who had a .50-caliber machine gun shot at me. It was all over the place, and I had no idea which way to go. I didn't do much dodging because I was just as likely to fly into bullets as around them."

When he hopped over the last row of trees and found himself crossing his own airfield, he pulled up hard to set up for landing. His mind was on flying the airplane. "I pitched up, pulled the throttle back and punched the buttons I knew would put the gear and flaps down. I felt the flaps come down but the gear wasn't doing anything. I came around and pitched up again, still punching the button. Nothing was happening and I was really frustrated." He had been so intent on figuring out his airplane problems, he forgot he was putting on a very tempting show for the ground crew.

"As I started up the last time, I saw our air defence guys ripping the tarps off the quad .50s that ringed our field. I hadn't noticed the machine guns before. But I was sure noticing them right then.

"I roared around in as tight a pattern as I could fly and chopped the throttle. I slid to a halt on the runway and it was a nice belly job, if I say so myself."

|

|

|

|

His antics over the runway had drawn quite a crowd, and the airplane had barely stopped sliding before there were MPs up on the wings trying to drag him out of the airplane by his arms. They didn't realize he was still strapped in.

"I started throwing some good Anglo-Saxon swear words at them, and they let loose while I tried to get the seat belt undone, but my hands wouldn't work and I couldn't do it. Then they started pulling on me again because they still weren't convinced I was an American.

"I was yelling and hollering. Then, suddenly, they let go, and a face drops down into the cockpit in front of mine. It was my Group Commander: George R. Bickel.

"Bickel said, 'Carr, where in the hell have you been, and what have you been doing now?

Bruce Carr was home and entered the record books as the only pilot known to leave on a mission flying a Mustang and return flying a Focke-Wulf. For several days after the ordeal, he had trouble eating and sleeping, but when things again fell into place, he took some of the other pilots out to show them the airplane and how it worked. One of them pointed out a small handle under the glare shield that he hadn't noticed before. When he pulled it, the landing gear unlocked and fell out. The handle was a separate, mechanical uplock. At least, he had figured out the important things.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carr finished the war with 14 aerial victories on 172 missions, including three bailouts because of ground fire. He stayed in the service, eventually flying 51 missions in Korea in F-86s and 286 in Viet Nam, flying F-100s. That's an amazing 509 combat missions and doesn't include many others during Viet Nam in other aircraft types. There is a profile into which almost every one of the breed fits, and it is the charter within that profile that makes the pilot a fighter pilot . . not the other way around. And make no mistake about it; Colonel Bruce Carr was definitely a fighter pilot.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

a private pilot since 1939, soloing in a $25 Piper Cub his

father had bought from a disgusted pilot who had left it lodged

securely in the top of a tree. His instructor had been an Auburn,

New York native by the name of 'Johnny' Bruns.

a private pilot since 1939, soloing in a $25 Piper Cub his

father had bought from a disgusted pilot who had left it lodged

securely in the top of a tree. His instructor had been an Auburn,

New York native by the name of 'Johnny' Bruns.