|

|

|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 46 Page 16 |

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

|

|

|

Smokey Blue.

Ron Raymond has been tapping away at, what he calls, “a sort of autobiography” of his long and varied career. The story so far comprises some 20 parts totalling 54,000 words and he says he thinks he’s about 2/3rds finished. He’s sent us a small part of what’s done to now which he says we can share with you.

We first met Ron in 1968 when we were posted to 38 Sqn Det A in Port

Moresby wher

L-R: P/O Stu Cooper, P/O Max Goodsell, F/L Nick Watling, Sqn Ldr Ron Raymond, F/L Gary Kimberley.

He was a very keen "yachty" and the waters around Moresby were perfect for his second love and most weekends he would be on the water. Not far from Moresby is a small island called Daugo Island which also contains an alternate aerodrome. Ron was very keen to ensure this small airport was maintained in a condition suitable for his 3 caribous and would often beg a barge from the Army to take the troops over on an inspection tour.

I left the RAAF in 1971, joined DCA as a Flight Service Officer and in 1973 was posted to Madang in PNG. In 1976 I was posted down to Moresby and ran into Ron again, he had left the RAAF and was flying the B-707 with Air Niugini. We saw him frequently in the briefing office until I left PNG in 1980 and returned to Australia. Ron stayed on with Air Niugini until he retired then moved to New Zealand where he now instructs at Massey University’s School of Aviation in Palmerstone North. Ron had a joust with stomach cancer over a year ago and even though he's been assured they got it all, they continue to monitor things on a quarterly basis. As a very active 80 year old, he still does the final simulator checks on graduates at Massey and being a keen sailor, still sails his boat north of Auckland.

While in the RAAF, Ron was posted to RTFV in Vietnam on the 30 Sept

1964.

The RAAF

The flight’s remaining three aircraft arrived on 29 August; making Ron one of the early birds.

This is his story.

“Early in the piece, we flew night flares out of Saigon. We were rostered as Smokey Red airborne to a target, Smokey Blue airborne awaiting a target and Green on immediate standby in an air conditioned trailer at Than Son Nhut. When a fort came under attack we were vectored to the target where a fire arrow was set ablaze and pointed in the direction of the VC with fire pots behind to indicate the distance to the enemy. We also carried a VNAF navigator to talk to the forts on FM PRC10 FM sets although I usually called on VHF.

Chris

Sugden and I flew the first flare job, a Smokey Blue over Saigon. We

droned around the outskirts of the city where to my surprise we

inspired sporadic 30 calibre ground fire, not that it was very

accurate but it certainly was a cheeky gesture on the fringe of the

national capital. To add further complication, we almost ran over a

number of ARVN airfield guards during our pre-dawn return to Vung

Tau; the soldiers found the pierced steel runway matting ideal to

bed down and barely escaped a grizzly end as our darkened aeroplane

rolled down the runway avoiding gallant, if prostrate, defenders.

Still I assumed they would ‘rise unto to the breach’ when the

occasion arose – or so I hoped. My second night involved a target

that took offense at our presence overhead and occupied itself

shooting at us by moonlight, a development justifying a call to

Paris and a response that, “They are friendly,” which triggered my

counter, “Please tell them we’re friendly too,” followed by an

observation from the co-pilot that remains unprintable in a family

story. Of

I usually returned to the villa feeling quite weary after a night’s work; often removing my shoes to flop onto the bed in my flight suit until mid-morning when I rose to shower away the smell of the evening’s ops before walking to the BOQ for morning coffee; perhaps something more substantial in the village; or simply a stiff Scotch if the night had been exciting and I was not flying later that day. Nevertheless on one memorable occasion I failed to stir in an accepted fashion; rather, I was jolted awake by gunfire that seemed close enough to be in the next room - really heavy gunfire; artillery: a six inch cannon or perhaps something larger although I had never been close to anything like that let alone heard one fired. Fearing an attack, I leapt off the bed slipped on my shoes, snatched up my pistol and stumbled to the stairs to find out who or what was shooting at whom. I was aware of my isolation as the only European in the building at the time, alone and waving a .45 pistol around to counter a NVA (North Vietnamese Army) attack. I even wished for the Garand however that was safely stored at the airfield where it could not fall into the wrong hands. By the time I reached the courtyard and crept around the building patchy gun smoke, or whatever smoke sailors used to celebrate things, was drifting across the Delta in the light morning breeze.

There in splendid array was a lone gunboat close inshore bedecked with signal flags and flying the yellow of the South with its three horizontal red bands, firing salutes to the world as it existed on the Mekong River. Quite an august performance that quickly developed into a display of loyalty to General Nguyen Khan who had just seized power from Big Minh (General Duong Van Minh) during a bloodless coup in Saigon. Curiously General Minh continued as Head of State despite being placed under indefinite house arrest: If all that is hard to grasp be assured it verged on unintelligible in the context of the time and remoteness of the Mekong; so confusing I called Saigon on our airfield link to ask the TMC people what was going on ‘up there’. Not that the call was much help for Chuck Case had an ARVN tank outside with its gun trained on the entrance to the building compounding a situation where the unexpected was undoubtedly next item on the agenda, all of which led to his abrupt apology and a deafening silence when he hung up. Obviously Ton Son Nhut had already gone to hell in a handcart.

As

the day developed it became obvious that air support out of Saigon

was out of the question until the national leaders sorted their

differences; there would be no C123s (right) out of Ton Son Nhut, no

VNAF navigator, no flare ‘kickers’ for RTFV, no fighters and little,

if any, artillery support for the forts we were supposed to defend.

Nevertheless I believed we had to do something more than just sit on

our hands and wait for the VC to overrun the place. We were still a

going concern with serviceable aeroplanes, fuel, flares,

flare-boxes,

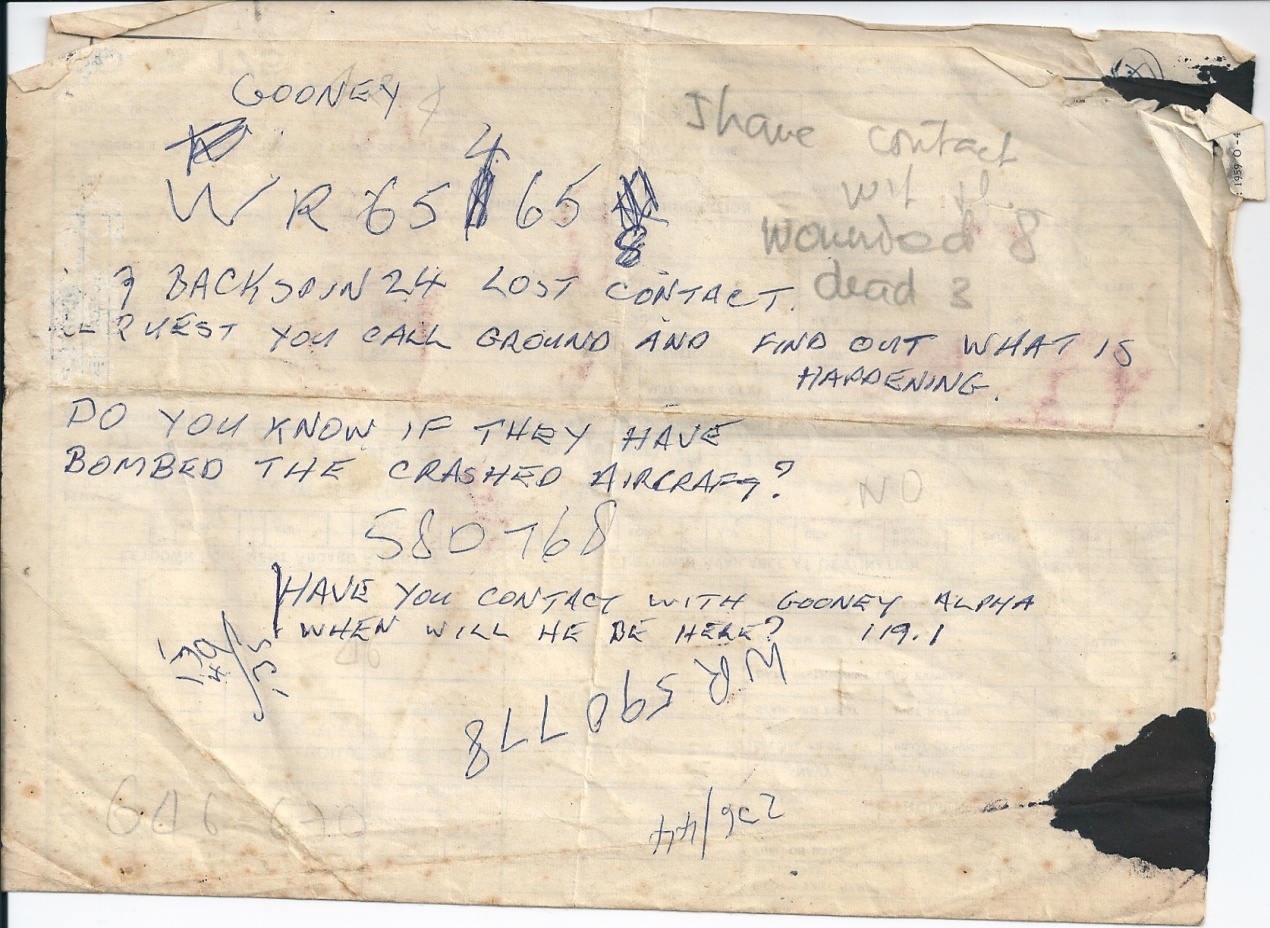

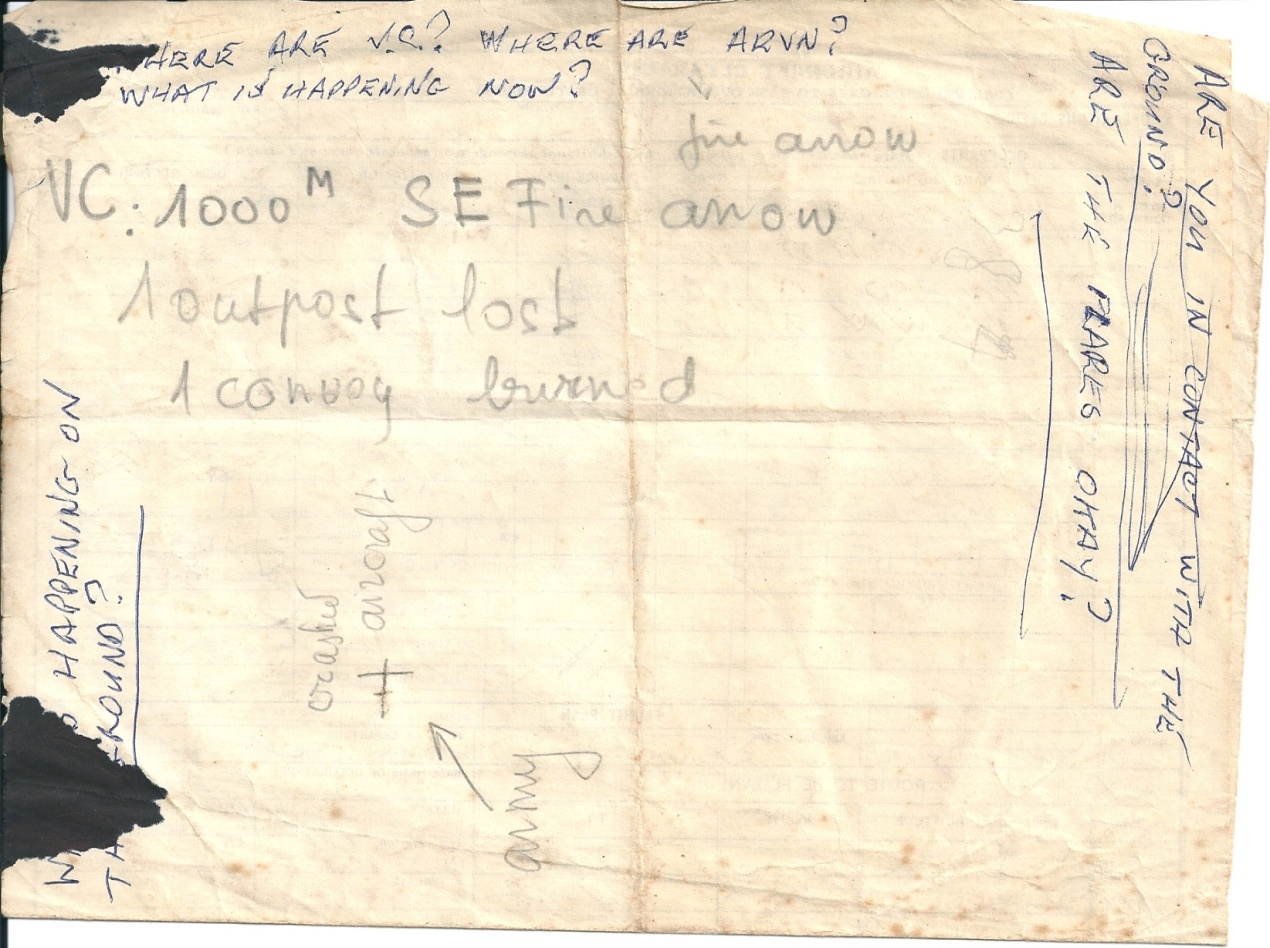

Our first call came with the night and radar vectors to a delta fort that triggered the Warrant Officer’s refusal to become part of any action outside his province; a fact relayed to me by the Interpreter when the soldier refused to call the friendlies as we approached the outpost in IV Corps (Mekong Delta). The Interpreter had tried to explain the desperate situation to the man, that one aircraft had already been lost in the action and that a relief convoy was at risk. I handed control to the co-pilot, climbed out of my seat (no small feat wearing a parachute in the confines of the cockpit) and tried to reason with the Warrant Officer who continued his refusal to make the call. The Interpreter joined me in an effort to convince the man; to appeal to his decency; his compassion for the villagers; his loyalty to his country and his duty as a soldier. I felt myself reaching an emotional limit at one stage, actually trembling as I struggled to contain my frustration. Finally I returned to the cockpit, resumed control of the aeroplane and had the co-pilot call Paris to request a Gooney flare ship, a Dakota from Bien Hoa or anywhere else, to take over the mission. I really didn’t care where it came from just as long as it had a VNAF person prepared to talk to the fort. In the event we found the fire arrow while all this was going on and set about establishing a race track flare pattern at 3,000ft while we waited.

The actual drop was done by eye, upwind so that the flares drifted to silhouette the VC, something that invariably irritated the communists and, if done correctly, triggered quite an aggressive response - in this case 0.50 calibre that came up in the most convincing demonstration of deflection shooting I had seen. Obviously there were professionals aiming the guns that night - or practiced irregulars who knew what they were about. The trick on encountering tracer was to evaluate its relative speed, if it soared towards us seemingly slowly, the aim was accurate; if it was random, moving fast in our general direction, it would miss: It was that simple - a tenet applicable in any collision situation for that matter. Not that the bullets actually travelled slowly but they did take a little time to reach 3,000 or 4,000 foot and appeared slower than those bound to miss. On this particular occasion, the gunner’s accuracy prompted me to douse our lights and climb an extra 1,000 foot, not that I thought we would out-fox the VC, but perhaps we might make their task as difficult as ours was becoming for us.

‘Gooney Alpha’, was being readied to take over the operation; a heartening gesture even though the aircraft never actually arrived; despite that it provided a morsel of hope that revitalised both the paratrooper NCO and me. I hastily scribbled a note on the back of our flight plan asking if he was in contact with the ground and if the flares were satisfactory? To my delight he responded, leading to the scribbled exchange I have retained over the years and pasted here as part of my story.

Sadly

the action ended when the Vietcong overran the fort, another win for

the VC when

The Controller called as we taxied into dispersal, it seemed his main generator had failed, the battery bank had been exhausted and the only way he could power up the flare path was to crank the generator over on the starter motor with his emergency battery. American professionals I met in Vietnam were invariably good men, ‘top troops’ and here was yet another: I thanked him for his help before we wished each other good luck and good night.

It

was not that we lost every engagement. Viet Cong and even the NVA

were reluctant to meet the combined American / ARVN forces in open

combat at that time and when they did they were invariably defeated

by technology and bombardment from land, sea and air.

We evacuated the aircraft to Butterworth next day. It was an uncomfortable ride through the fringe of the storm without benefit of either weather radar or navigation aids across the Gulf of Thailand. Nevertheless it was only a four hour flight and we were prepared for rough stuff anyway. Not that I care to sound blasé about it all, however I had developed an attitude towards our operations that left me indifferent to most exigencies, indifferent to anything short of structural failure or fire - two possibilities that defied contemplation. However when it came to a simple matter of crew and aeroplane versus wind and weather, that was a piece of cake.

Our arrival at Butterworth coincided with the Officer’s Mess opening. We arrived at 5PM and settled around the bar with chilled Tiger Beer; a vast improvement on our watering hole in Vietnam where we cooled our tipple with ice helicoptered in from Saigon, chopped into manageable blocks with an axe, secured in plastic bags and battered with a blunt instrument to be added in smaller lumps to glasses of warm Beer33. Something akin to a horror story for the connoisseur but God’s gift to beer starved grunts and dehydrated flight crew.

Saturday night was the big night of the week, a high point of life

in the village and a time when the bars, tarts and touts lay in wait

for lustful and unwary soldiers. There we

Apart from that, the passage of the night was generally peaceful enough. I met any number of Vietnamese during my tour and although contact was fleeting I found better class women in their national dress (the Au Dai) delicate, elegant, and wise enough to remain distant from foreigners who were ‘saving’ their country on one hand while infecting it with virulent strains of STD on the other – all of which begged the question: just what was it all about? Was it a battle against communism or a struggle for independence that brought the whole ghastly experience on them? Unfortunately so much has been said and written about the war to no real avail that there is little point in amplification here. Most affluent women were gracious and extremely conscious of skin texture and colour – I never saw one in a swim suit either out of or in the water on Vung Tau’s ‘Back Beach,’ South Vietnam’s answer to the Rivera. In the days of French colonialism the village had been seen as the genteel holiday destination of choice for the Saigon glitterati. Sadly in pursuing the political aim to save the nation; the attrition of husbands, fathers and siblings reduced many middle and lower class women to a level of poverty and prostitution. But then such has been a by-product of military intervention for time immemorial.

Not

that the male of the species should be denigrated as contemporary

life in the region produced demands foreign to a European mind. I

still believe reluctance to pursue an enemy into a maze of punji

stakes, booby traps, ambushes and often overwhelming odds showed

tactical sense rather than cowardice or reluctance to fight. The

persistent sacrifice of young men by General Giap and his henchmen

later in the war exceeded any definition

An early experience of Vietnamese dedication involved a medical doctor and a search for supplies destined for Ban Don – an airstrip with the thought provoking arrival sign:

“WELCOME TO BAN DON “ WATCH OUT FOR ELEPHANTS.

On the day, the medic approached me concerning a consignment that had not been included on the aircraft’s manifest, a discrepancy that concerned us both to the point of harassing the air movements and stores people until we made sufficient impact to initiate a search. Something that seemed trivial – just one item of cargo out of all the freight carried that day - but important enough for the doctor to become deeply concerned. At one stage we were in a Da Nang cargo shed actually looking into freight containers with the shed supervisor before we checked the loaders on the ramp and staff in Air Movements. The search lasted over an hour but finally we were successful and the doctor marched triumphantly to the aircraft with his 24 inch plywood box of treasure. I left the doctor at Ban Don, clutching his supplies in case they evaporated before his eyes: “God bless you Dai Uy,” he said offering his hand and exuding gratitude from just about every pore, “You will remember me?” I smiled at his simple request, “Yes Doctor, I will certainly do that,” I replied. I have remembered him to this day although God alone knows his ultimate fate.

After two nights and a day the Typhoon Report was downgraded to Tropical Storm status and we could no longer justify a leisurely life in Malaysia. Accordingly, we planned back across the Gulf of Thailand; obtained a weather confirming the storm’s decreasing intensity over Vietnam and, although the actual rain observation was still moderate to heavy, it became a simple matter of ‘kick the tyres, light the fires – first one in the air is the leader.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alien Intelligence.

Bob Webster.

There

are a lot of stars in the sky. About 9,000 are visible with the

naked eye, 200,000

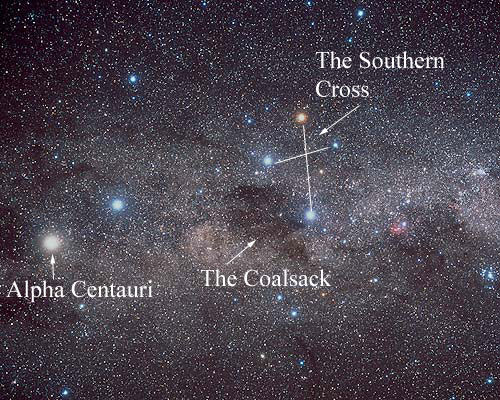

But with high powered telescopes and a little math, we can estimate 400,000,000,000 stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way. With around 170 billion galaxies, give or take a dozen, there may be about 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,003 stars in the universe. (See HERE)

The law of probability says some of those would have planets and some of those planets would have environments similar to earth. It seems likely that some of those planets might have life and some of those with life would have intelligent life.

Sure, you say. Why would there be intelligent life elsewhere when there is none on earth? The fact is, not everybody is as dumb as me. Some people have a brain, and a few actually put them to use and they work out stuff like this.

Let's say, for the purposes of discussion, that there are people (or something similar, such as politicians) on other planets. Why haven't we met any?

The answer is simple, they are too far away, there is a speed limit and it takes a long time and a lot of energy to get to another habitable planet.

If we could travel at the speed of light, the ultimate speed limit, it would still take over a million years to get to 99.9999999999% of the stars flying around the universe. OK, how about traveling to one of the closer stars? There are 50 stars within about 16 light years of earth. Let's pick the closest, Alpha Centauri, about 4 light years away.

We'll build a nuclear pulse rocket. We'll just send the Alpha Centaurians an ipod with some music on it. That way we won't need to worry about food, water, air, radiation shielding, or a piano for human passengers.

Making a one-way trip in a reasonable time frame (130 years) will require a spaceship of about 100,000 tons, just to deliver our ipod to Alpha Centauri. At the moment, that's a little heavier than we can lift into earth orbit in one launch. So let's give up on interstellar travel. We'd need better technology so let's just send a radio message to the 50 nearest stars. The problem is, even if they get the message, we won't "hear" the reply with our current technology. It would be far too weak.

If there is intelligent life on other planets, why don't we receive radio transmissions from them? They should be communicating somehow on the electromagnetic spectrum, and we would notice non-random modulations.

There's an organization called SETI that listens for extra-terrestrial life. They have not found any but there's a good reason. If they were sitting on Alpha Centauri listening to earth, they wouldn't hear anything either.

What about aliens detecting our radio transmissions? There has been radio on earth for about 100 years. Marconi's signals have only now reached the nearest 10,000 stars.

If there is intelligent life on other planets, why haven't they come here? It's not likely a civilization would or could send probes to the nearest 1000 planets because it's too expensive and it takes too long. If alien civilizations did explore other star systems, the odds are strongly against any of them coming to ours because of the number of other stars and the time and energy required for interstellar travel. Even with technology much more advanced than ours, the energy and time requirements would be huge.

The conclusion is that if there is intelligent life on other star systems, it would be very unlikely for us to know about them or them about us.

You might have noticed that I have not mentioned warp drive, jump drive, wormholes, or other modes of faster than light travel you can read about in science fiction novels. If they exist (and it’s a big IF), that could change everything.

You can read further info HERE.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nurses.

Chrissy Martin sent us this.

A list of rules for nurses. from 1887

Whether you’re a new nurse or a seasoned nurse, it’s always intriguing to take a look back at the history of the nursing profession. This list illuminates the day-to-day tasks and regulations pertaining to the life of a nurse in 1887—before routine charting was even invented.

1887 Nursing Job Description

In addition to caring for your 50 patients, each bedside nurse will follow these regulations:

1. Daily sweep and mop the floors of your ward, dust the patient’s furniture and window sills. 2. Maintain an even temperature in your ward by bringing in a scuttle of coal for the day’s business. 3. Light is important to observe the patient’s condition. Therefore, each day fill kerosene lamps, clean chimneys and trim wicks. 4. The nurses’ notes are important in aiding your physician’s work. Make your pens carefully; you may whittle nibs to your individual taste. 5. Each nurse on day duty will report every day at 7 a.m. and leave at 8 p.m. except on the Sabbath on which day she will be off from 12 noon to 2 p.m.

6.

Graduate nurses in good standing with the director of

nurses will be given an evening off each week for courting purposes,

or two evenings a week if you go regularly to church.

7. Each nurse should lay aside from each payday. a goodly sum of her earnings for her benefits during her declining years, so that she will not become a burden. For example, if you earn $30 a month, you should set aside $15. 8. Any nurse who smokes, uses liquor in any form, gets her hair done at a beauty shop or frequents dance halls will give the director of nurses good reason to suspect her worth, intentions and integrity. 9. The nurse who performs her labours [and] serves her patients and doctors faithfully and without fault for a period of five years will be given an increase by the hospital administration of five cents per day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

e Ron was the very popular Sqn Ldr CO.

e Ron was the very popular Sqn Ldr CO.

course they really weren’t friendly at all for the ground

fire emanated from the Viet Cong force that had overrun the outpost

shortly before our arrival. At this stage it seemed that ‘flying

flares’ was just the ticket to liven up an otherwise dull evening in

Indo China.

course they really weren’t friendly at all for the ground

fire emanated from the Viet Cong force that had overrun the outpost

shortly before our arrival. At this stage it seemed that ‘flying

flares’ was just the ticket to liven up an otherwise dull evening in

Indo China.  flare chute and nucleus of a crew. I turned to our

friends, the local Parachute Battalion, who offered a brace of

kickers and a Warrant Officer to fly with us; I prevailed on our

Interpreter to come along as backup. I called TMC where the mood was

merely tense, rather than grim defeatism experienced earlier, and

received grateful agreement to mount a Smokey Green standby out of

Vung Tau under the auspices of Paris Control. I began to feel we

were becoming operational again so I moved my kit to our

Headquarters on the airfield where I had access to a telephone, a

radio, direct contact with air traffic control and our engineers.

Not that the airfield accommodation was anything to write home about

for although it exceeded whatever the grunts might have in the

boonies, it lacked about every basic ingredient normal people

consider essential, even providing mosquitoes, malaria and monsoon

driven sand over everything. I cannot recall Chris in Vung Tau

during all that: I imagine he must have been north on TDY.

flare chute and nucleus of a crew. I turned to our

friends, the local Parachute Battalion, who offered a brace of

kickers and a Warrant Officer to fly with us; I prevailed on our

Interpreter to come along as backup. I called TMC where the mood was

merely tense, rather than grim defeatism experienced earlier, and

received grateful agreement to mount a Smokey Green standby out of

Vung Tau under the auspices of Paris Control. I began to feel we

were becoming operational again so I moved my kit to our

Headquarters on the airfield where I had access to a telephone, a

radio, direct contact with air traffic control and our engineers.

Not that the airfield accommodation was anything to write home about

for although it exceeded whatever the grunts might have in the

boonies, it lacked about every basic ingredient normal people

consider essential, even providing mosquitoes, malaria and monsoon

driven sand over everything. I cannot recall Chris in Vung Tau

during all that: I imagine he must have been north on TDY.

I

I thought the ‘good’ guys always won. I could have wept.

We tried so bloody hard to win that one, an action that lasted over

six exhausting hours; hand flying; stinking of cordite and smoke

from the fort; blinded by the flames and smoke from the village; the

glare of the flares; sweat soaked flak vests; sweat soaked flight

suits; sweat running over our faces from our helmets; sickened by a

vision of the ghastly end on the ground; awed at the ground fire

coming our way once the outpost fell. I climbed another 1,000ft,

called Paris and turned for ‘home’. Even then the night was not done

with us; Home Plate (Vung Tau airfield) could only muster the

faintest glimmer of what was once a glowing flare path; something we

might lose at any moment. We swept into the circuit and descended

onto final approach, hardly daring to take our eyes from the apology

of a flare path; the co-pilot calling height and airspeed as I lined

up on the flickering lights - down, down, across the threshold, into

the landing flare. Thankfully there were no aerodrome guards asleep

on the runway.

I

I thought the ‘good’ guys always won. I could have wept.

We tried so bloody hard to win that one, an action that lasted over

six exhausting hours; hand flying; stinking of cordite and smoke

from the fort; blinded by the flames and smoke from the village; the

glare of the flares; sweat soaked flak vests; sweat soaked flight

suits; sweat running over our faces from our helmets; sickened by a

vision of the ghastly end on the ground; awed at the ground fire

coming our way once the outpost fell. I climbed another 1,000ft,

called Paris and turned for ‘home’. Even then the night was not done

with us; Home Plate (Vung Tau airfield) could only muster the

faintest glimmer of what was once a glowing flare path; something we

might lose at any moment. We swept into the circuit and descended

onto final approach, hardly daring to take our eyes from the apology

of a flare path; the co-pilot calling height and airspeed as I lined

up on the flickering lights - down, down, across the threshold, into

the landing flare. Thankfully there were no aerodrome guards asleep

on the runway. However our

night operations remained a simple matter of being shot at while we

orbited the scene dropping flares. In this regard we were diverted

from a Smokey Blue to support a delta outpost one dark and dismal

evening; an occasion when weather would normally protect the VC from

flare ships. That night the weather was certainly an inconvenience,

forcing us below a scrappy overcast at 2,300ft in an effort to

orientate a drop pattern on the fire arrow with the flares set to

ignite below 2,000 – leaving us silhouetted against the overcast by

our own flares. To further complicate things the lower altitude

meant the flares ignited shortly after launch and were still burning

when they hit the ground – a situation requiring a tighter circuit

and more frequent flare despatch to maintain illumination over the

enemy. To my surprise there was no tracer fire however the fort

warned the navigator that the VC was shooting at us. While there was

not a lot we could do about that, the lack of tracer probably meant

absence of heavy automatic weapons, so we just ‘carried on’ in the

words of the sage. A reaction that proved appropriate when the fort

advised that the VC had withdrawn and thanked us for our help. As a

reward for our efforts Paris passed a typhoon warning valid for the

next 48 hours.

However our

night operations remained a simple matter of being shot at while we

orbited the scene dropping flares. In this regard we were diverted

from a Smokey Blue to support a delta outpost one dark and dismal

evening; an occasion when weather would normally protect the VC from

flare ships. That night the weather was certainly an inconvenience,

forcing us below a scrappy overcast at 2,300ft in an effort to

orientate a drop pattern on the fire arrow with the flares set to

ignite below 2,000 – leaving us silhouetted against the overcast by

our own flares. To further complicate things the lower altitude

meant the flares ignited shortly after launch and were still burning

when they hit the ground – a situation requiring a tighter circuit

and more frequent flare despatch to maintain illumination over the

enemy. To my surprise there was no tracer fire however the fort

warned the navigator that the VC was shooting at us. While there was

not a lot we could do about that, the lack of tracer probably meant

absence of heavy automatic weapons, so we just ‘carried on’ in the

words of the sage. A reaction that proved appropriate when the fort

advised that the VC had withdrawn and thanked us for our help. As a

reward for our efforts Paris passed a typhoon warning valid for the

next 48 hours. re unspoken rules

forbidding the presence of firearms but acceptance of ‘bar girl’

overtures to likely clients; approaches involving salacious

greetings that were about as subtle as a train crash - something

like, “You cherry boy, me number one – you buy Saigon tea?” Saigon

tea was a cheap mix of cordial sold at exorbitant prices to line the

pocket of spivs and charlatans who infected the place. It was not

that Vietnamese women were immoral for like their gender worldwide

they were, and are, the strength of the race.

re unspoken rules

forbidding the presence of firearms but acceptance of ‘bar girl’

overtures to likely clients; approaches involving salacious

greetings that were about as subtle as a train crash - something

like, “You cherry boy, me number one – you buy Saigon tea?” Saigon

tea was a cheap mix of cordial sold at exorbitant prices to line the

pocket of spivs and charlatans who infected the place. It was not

that Vietnamese women were immoral for like their gender worldwide

they were, and are, the strength of the race.  of callous disregard. The NVA consistently lost to American technology and methodology yet

continued sending men into combat in ever increasing numbers: I

suppose that was one way to win a war.

of callous disregard. The NVA consistently lost to American technology and methodology yet

continued sending men into combat in ever increasing numbers: I

suppose that was one way to win a war.

with a good pair of binoculars, and a couple hundred thousand stars

can be seen with a small telescope. That's a lot of stars.

with a good pair of binoculars, and a couple hundred thousand stars

can be seen with a small telescope. That's a lot of stars. The

best SETI experiments to date could detect earth-strength signals at

a maximum distance of one light year. They'll have to be a couple of

hundred times more sensitive to detect signals from the nearest 50

star systems (or the other radio transmissions will have to be a

couple hundred times more powerful.)

The

best SETI experiments to date could detect earth-strength signals at

a maximum distance of one light year. They'll have to be a couple of

hundred times more sensitive to detect signals from the nearest 50

star systems (or the other radio transmissions will have to be a

couple hundred times more powerful.)