|

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||||||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||||||

|

My Story.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

MY SERVICE YEARS.

Jock Cassels. RAF - 1941-1966 RAAF - 1966-1979

The War Years.

I turned 18 on 11 August 1941 and a few days later went to the RAF recruiting office in Glasgow to offer my services for pilot training. My details were taken and I was given a railway travel voucher and told to report to the Recruiting Centre in Edinburgh on 8 September to be enlisted. I reported in my Air Training Corps uniform taking with me my personal documents from the Squadron. I’ve forgotten all the various aptitude tests I had to do but I remember that the medical examination was quite extensive. My attestation was to be done the following morning, so I stayed overnight in the Armed Forces Transit Dormitory located at the main railway station (Princes Street Station) and I think it was run by the Salvation Army.

This was a huge dormitory full of two tiered bunks arranged in groups of four. I didn’t get much sleep due to the noise of service men coming and going all night, also for another reason; during the night I became aware of a bearded sailor looking at me for a while then mumbling something about me moving over to join him. In spite of my lack of knowledge of the seamier side of life I knew instinctively that his intentions were less than respectable and told him I preferred my own company. Needless to say there was no more sleep for me that night and I was up early and first in the breakfast queue. An introduction to the hazards of life you might say. I completed the recruiting formalities and was duly enlisted on 9th September 1941 as 1560768 Aircraftsman 2nd Class (the lowest rank) and accepted for pilot training. The training schools were full, so I was told to return home and await my callup. In the meantime, I continued with my Air Training Corps training.

After 5 months my call up papers arrived and I left Scotland for the first time on 1st March 1942 travelling by overnight train to London where I reported to No 1 Aircrew Recruiting Centre (ACRC) on 2 March 1942.

ACRC Recruits were accommodated in a block of high rise flats in St Johns Wood which had been commandeered by the RAF. Messing facilities were provided in an adjacent building. The famous cricket ground at Lords had been taken over by the RAF and it was there that we underwent our initiation into the service i.e. Issue of kit, drill practice, medical inoculations and vaccinations and general service indoctrination. It was all very bewildering to me but my ATC training helped me adjust quickly. We were kept very busy “learning the ropes” and didn’t have much time off, however what time we did get I spent wandering around the sights of central London. Coming from a small country town, the hustle, bustle and sheer size of wartime London left me in complete awe.

Shortly after arriving at ACRC we were advised that we would be going overseas to do our pilot training, either Canada, South Africa or Southern Rhodesia. After completing our initial training (two weeks) I was given 7 days embarkation leave, which I spent at home saying my farewells. The next move was a troop train journey from London to No 7 Personnel Despatch Centre (PDC) at Blackpool on 1st April.

At the PDC In Blackpool, the very popular holiday resort in the North of England, we were accommodated in private houses leased by the RAF. In peacetime these private houses were rented by people on holiday and the landladies were only too pleased to provide accommodation and messing to the RAF. A wartime bonanza for them.

Apart from being issued with tropical kit, which ruled out Canada, we spent most of the time just hanging about waiting for the next move.

An amusing episode occurred at this time. We were advised that we were likely to be on a troopship for a long time and to get our hair cut short before embarking. One recruit, a tall good looking chap who fancied himself with the girls, decided to comply with this advice and had his head shaved. Unfortunately, he was taken off our Draft at the last minute, due to excess numbers and was left behind with no hair which no doubt cramped his style with the girls for some time.

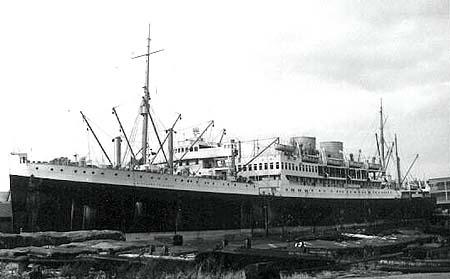

Another troop-train journey, this time from Blackpool to Avonmouth, a port near Bristol where we embarked on the “Highland Princess” a Royal Mail Line ship converted for troopship duties. This was the shipping line which I had tried to join in 1941 so I did eventually get to travel on one of their ships, not as crew but as a recruit pilot on Draft 4062. How ironic!

The Voyage.

Draft 4062 - UK to Rhodesia We sailed on 13 April 1942 and travelled up the Irish Sea to Scotland, anchoring just off Greenock in the Clyde estuary which was the assembly area for all the ships which were to form the convoy. The next day the convoy set sail into the North Atlantic with an escort of a number of warships. I can’t recall the number of ships in the convoy but it was a large number and included several troopships as well as numerous cargo ships. We had quite a large number of escorting warships, due no doubt to the presence of the troopships. As I found out later not all the ships were heading for the same destination for when we had been at sea for several days and well out into the Atlantic the convoy split, some ships continuing westward, presumably to America and Canada, while the remainder headed in a South West direction. I can’t remember if the convoy had any air cover but I’m sure we must have had, at least until short of the half way mark across the North Atlantic which was the limit of the range of the escorting aircraft.

After 3 weeks during which we must have travelled close to America and to the North of South America, we turned East for Africa and arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone. This was a refuelling and watering stop and convoy reassembly point for all convoys sailing in the North and South Atlantic. We didn’t get off the ship. I think we were there for just 24 hours then set sail again in convoy. Again we headed West and while no land was visible we must have travelled down the east coast of South America before turning East towards South Africa. Up to this point, as far as I am aware, there had been no submarine activity against our convoy but when we were south of Capetown the convoy was attacked at dusk and a couple of merchant ships were sunk. The troopships were always positioned in the centre of the convoy with the cargo ships located on the perimeter and I remember all being assembled on deck with lifejackets secure, watching the smoke from the sinking ship on the distant horizon and the warships rushing around dropping depth charges. Two days later, on 21st May 1942 we arrived at our destination which was Durban.

Before I narrate the last leg of the journey from Durban to Rhodesia a few words about the conditions on board a troopship in time of war would be of interest. We were accommodated below deck in a large mess hall with long tables and benches fixed to the deck. This is where we ate and slept. I think it was twelve men to a table and meals were collected in bulk from a central kitchen by whoever from the table was rostered for the task. At night we collected a hammock from a store at the end of the mess hall and slung the hammock from hooks located above our table. In the morning we had to roll up the hammock which had your number and return it to the store. Once all the hammocks had been slung there was not much room between them and people who snored or emitted other noises were not very popular.

After a few nights in this strange “bed” I found it quite comfortable to sleep in. Our kit bags containing our personal possessions, were located anywhere you could find a spot. Whenever we could, we spent as much time on the open decks as the weather allowed, particularly in the tropics as it was pretty hot down below. Generally the daily routine was pretty monotonous but we were given lectures on various topics suited to our situation, which helped. Apart from the attack on the convoy towards the end of the voyage it was an uneventful, somewhat boring, 6 weeks.

Durban to Rhodesia We didn’t spend much time in Durban, I think it was only one night, but it was marvellous to be back on dry land after nearly 6 weeks on the troopship. There was no blackout and it was strange to be walking down the street ablaze with light and the shops full of all the delightful food and confectionaries which we hadn’t seen for years. The following morning we were bundled onto a troop-train and set off for Rhodesia. The longest train journey I had previously undertaken was from Glasgow to London (9 hours) so it was an enlightening experience to spend the three days and two nights it took to reach Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia. On arrival we collected our kitbags and marched to the Initial Training Wing (ITW) which was located on the outskirts of Bulawayo.

Pilot Training.

Initial Training Wing – Bulawayo. The task of the ITW is to train cadet pilots in all the ground subjects required before they started their flying. The main subjects were Navigation, Theory of Flight, Meteorology, Aircraft Engines, Aircraft Recognition, Airmanship and other Service related subjects. We couldn’t start the course immediately as there was a logjam at the flying training schools, so we spent nearly 3 months in various time-filling activities such as drilling (of course), bush survival training, lectures etc. The bush training was interesting and consisted of being dropped off in an isolated area, provided with a compass and rations and told to find our way to a designated spot, several walking hours away, where our “rescuers” would be waiting. Much more interesting than drill. I should add that the areas involved were not the normal habitat of dangerous animals, eg lions.

Our off duty hours were usually spent off camp in Bulawayo enjoying the hospitality of the local populace. We, a fellow Scot, named George Gellatly, and myself, were fortunate to get to know a nice couple who made us welcome in their home and we spent many enjoyable evenings with them. The husband arranged for us to spend our two weeks leave on a farm well out in the bush where the farmer showed us how to hunt local buck, (something like a Springbok), and what isolated life was like in the Rhodesian bush. I should mention that it was at ITW that I had my first taste of alcohol when my more worldly colleagues persuaded me to have a bottle of beer in the camp canteen.

I remember that it had a rather “silly” effect on me and it was many months later before I became a beer drinker.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Eventually the ITW course started and after 3 months and successfully passing the course I was posted to No. 25 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) in Salisbury which was the capital of S Rhodesia, about 300 miles north of Bulawayo.

Elementary Flying Training School.

December 14th, 1942 saw me get into the air for the first time when I had a flight of 1 hour with my instructor in a Tiger Moth aircraft. A great experience and one which I thoroughly enjoyed and will always remember. It was expected that most students would have their first solo flight after about 10 hours dual instruction and if they hadn’t gone solo by that time then their suitability to continue pilot training was examined. In my case after 9 hours my instructor, a rather grumpy Flight Lieutenant, obviously thought I wasn’t ready and handed me over to a young Pilot Officer and after a further 3 hours instruction I had my solo test by an independent instructor and on 23 December I flew solo for the first time. Looking back on it now I think the first instructor was a bit impatient at my progress and I became worried in case I made mistakes, which didn’t help. I was much more relaxed with the young Pilot Officer and he with me so I progressed very quickly when he took over.

My log book shows that I completed the course with 84 hours flying time and a Pilot rating of average. It also shows that I did not show any aptitude as a pilot navigator and this was the result of a silly error on my part during a pilot navigation test. Details of the trip, details such as compass heading, true heading, speed etc. is written down on a knee pad with the speed and heading columns being next to each other. When I was turning onto the second leg of the trip I put my speed (95) onto the compass instead of the heading (170). After a few minutes when my instructor asked why I was heading East instead of South I realised what I had done. A major error and the criticism I received was fully deserved, hence the poor rating. So ended 25 EFTS and on 20 Feb 1943 I was posted to 33 Course, No. 20 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) at Cranbourne (now called Harare), again an airfield just outside a major town, Salisbury. Service Flying Training School

Harvard - 20SFTS - 1943.

Advancing to a more powerful aircraft meant an advancement in rank and arrival at SFTS meant promotion to Acting Sergeant Unpaid (ASU) but it didn’t mean more pay or increased authority, just made us feel more important. We lived in the Sergeants Mess but being acting and unpaid we were treated as lesser mortals by the real Sergeants.

The course was divided into two phases, initial and advanced, each phase consisting of approx 80 flying hours. The aircraft was a Harvard, a low wing monoplane in which later I was to spend a large part of my flying career. I quickly adjusted to the more complicated cockpit controls and 3 days into the course and after 4 hours dual instruction I went solo. After 2 months and 77 hours flying I completed the initial phase and had a week’s leave before starting the advanced phase. Now was the time to apply our flying to learning the more warlike activities of formation flying and bombing and gunnery, while continuing to improve our basic flying skills, and after 2 months and 81 hours I completed the course with an average rating as a pilot and pilot navigator and recommended for single engine aircraft i.e. Fighters.

The long-awaited day had arrived and I received my pilots brevet (Wings) on the 10th July 1943 not as a Sergeant Pilot as had been my aim but as a newly commissioned Pilot Officer, for shortly before the course ended I had become an officer cadet and moved into the Officers Mess. My new designation now became 146889 Pilot Officer Cassels, General Duties Branch. Thinking back, I now realise that my training and conduct in the Air Training Corps must have resulted in my Squadron CO giving me an assessment as a likely candidate for commissioning.

I would like to digress for a moment to mention a non-service part of my time in Salisbury. My faith was still strong and every Sunday I went to the Presbyterian Church in town and eventually decided that I wanted to be confirmed. I attended confirmation classes in the evening, when not on duty, and was duly confirmed in March 1943. Through the church I got to know the Brown family who took me under their wing and I spent many happy days enjoying their generous hospitality.

Having successfully completed Elementary and Service flying training I was now ready to proceed to the next phase which was Operational training. This was carried out at Operational Training Units (OTU’s) and involved training on the aircraft on which a pilot would be flying against the enemy. In my case this was to be on single engined aircraft i.e. Fighters. There were three likely places to be sent - back to the UK, north to the Middle East or east to South East Asia . I and the other members of the course who were commissioned were posted to the Middle East while the majority of the course, the Sergeants, were posted back to the UK. I was quite pleased with my posting for it was another new part of the world for me to see but it was with a tinge of sadness that I was leaving Southern Rhodesia, a lovely country and the people who had been so kind and generous to me.

The Middle East! How was I going to get there - by air, by land or by sea. Well, much to my surprise it was to be by land, at least part of the way; I had assumed it would be by air. There was a contingent of African troops being moved to the north and we were to join them on the journey which was to start at Bulawayo. So on the 15th July 1943 we started our journey.

Rhodesia To Cairo.

These days people pay a lot of money to travel from Cape to Cairo but here I was travelling over roughly the same route and being paid to do it. Admittedly the comfort comparison is vastly different but there was a war on and we were on duty.

The journey started with train travel from Bulawayo-Victoria Falls into Northern Rhodesia, Lusaka, Broken Hill then into the Belgian Congo (now called Zaire). We detrained somewhere in the Belgian Congo (can’t remember where) and then travelled by truck over some shocking tracks, which no way could be called roads, the corrugations on which gave us a real bone shaking ride. Fortunately, it only lasted about 15 hours when we again had a train journey to Albertville on Lake Tanganyika. There a steamer awaited us and we set off to the northern reaches of the lake. After our train and road journeys the peace and quiet of the lake trip was heaven and the day and a bit it took us to get to our destination enabled up to recuperate somewhat, for we had been travelling non-stop for over a week. I can’t remember the name of the place at the northern end of the lake but it was in Tanganika and we again entrained for the 2 day journey to the southern end of Lake Victoria. Again onto a steamer at Mwanza for the “voyage” to Kisumu in Kenya which took about a day. So far we had been traveling nearly two weeks and imagine our delight when we were told that the rest of our journey to Cairo would be by BOAC Flying Boat. It was here that we left the troops - where their final destination was I have no idea.

On 29 July we left Kisumu on a flying boat called ”Caledonia” for a short flight to Port Victoria where we spent the night in a hotel - delightful - and on the 30th flew from Port Victoria to land on the river Nile at Khartoum in the Sudan, a flight of 8 hours. Next day, 31 July, after a 7 hour flight we reached our destination, landing on the river Nile in Cairo. An exhausting and at times uncomfortable 16 days of travel but an experience not to be missed.

The Middle East.

My first impressions of Cairo were of a crowded city of hustle and bustle Military and civilian vehicles all sounding their horns fighting for the right of way in the crowded streets, with the local Arab hawkers on their donkeys and carts going about their business adding to the traffic mayhem. And Servicemen by the thousands, mainly Army and Air Force, some on leave, some in transit and some based in the city. Add the typical Middle East smells, some pleasant some not so, and you have wartime Cairo.

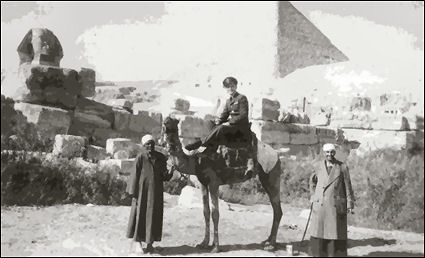

On arrival we were sent to No 22 PTC (Personnel Transit Centre) at Almaza which was a vast tented camp on the outskirts of Cairo. There we waited for 7 days and I took the opportunity to take in the sights of Cairo including a visit to the Pyramids where I had the customary photo taken, mounted on a camel, with the Pyramids in the background.

Cairo, Egypt - 1943.

The next move was to No. 1 Middle East Aircrew Reception Centre at

Cassareep beside the Great Bitter Lake just south of Ismailia. This time

there were no tents but barrack type accommodation which, considering

the location and times, could be considered very comfortable. This was a

very

Operational Training No 73 OTU was located at Abu Suweir near Ismailia and was a pr-war RAF airfield. Training was conducted on two types of operational aircraft, the Spitfire and an American aircraft the Kittyhawk. I was posted to the Spitfire flight. There were Australians on our course and they went to the Kittyhawk flight as there was an Australian Kittyhawk squadron operating in the forward areas.

To refresh our previous training we did about 20 hours on Harvards

before converting onto the Spitfire. When on the ground and on the final

stages of landing the forward visibility of the Spitfire was limited due

to the long and wide engine, so some of our training in the Harvard had

to be flown from the

73 OTU Abu Suweir - 1943.

I had just become more acquainted with my new aircraft when a week later I was involved in a motor accident and landed in hospital. For some reason, I’ve forgotten what it was, the course had to visit the adjacent airfield at Ismailia, about 20 miles away. We were transported in a flat top lorry with side railings but an open top. On the return journey it started to drizzle, a most unusual event in that part of the world, and the lorry got into a skid and overturned. We, about 20 of us, were flung out and as far as I can remember I was the only casualty. Apparently, I went head first onto the road and was knocked unconscious. Anyway, I woke up in the RAF Abu Suweir hospital where I stayed for 2 weeks being treated for concussion. I was given 2 weeks sick leave then had a medical check before being passed fit to continue flying. This was a setback to my training as I was put back 2 courses and it was late November before I resumed flying. A quick check on the Harvard then I spent the rest of the course on the Spitfire learning how to apply the combat capabilities of the aircraft. This involved formation flying, air to air and air to ground gunnery and fighter tactics.

The air to ground gunnery was interesting for it involved two aircraft using the gunnery range, which was located in a remote part of the desert. The target aircraft would fly at about 1500 feet casting a shadow on the sand at which the other aircraft would fire. Of course, strict safety procedures had to be observed. It’s worthy of mention, but you could always tell when a pilot was having his first trip in a Spitfire, for the undercarriage lever was located on the right side of the cockpit and to raise the wheels after take-off you had to transfer the left hand from the throttle onto the control column and use the right hand to operate the undercarriage lever. This manoeuvre resulted in an unintended fore and aft movement of the control column which, because of the very sensitive elevators, caused the aircraft to pitch up and down.

I completed the course on 24 December 1944 with 23 hours on Harvards and 44 hours on Spitfires being assessed as average in the three categories - Fighter Tactics, Formation Flying and Pilot. Two days later I was posted to the Personnel Transit Centre at Almaza in Cairo, where I had been when I first arrived in Egypt. A week of hanging around then I was given my next posting, which was to another holding unit in Tunis Egypt to Italy.

On the 8th January 1944 I left Cairo in a South African Air Force Dakota and landed at Castel Benito near Tripoli. Here I stayed for 2 nights and it was here that I met my first Russians. They were a Russian Air Force crew flying a Dakota but why they were there I have no idea, but at this stage in the war they were on our side. I remember that their uniform was a dark shade of brown in colour and the next Russians I was to meet was under very different circumstances. My next stop was Tunis, again by SAAF Dakota, where I remained for 11 days awaiting my posting to what I hoped would be my final destination. Our accommodation this time was not in tents and was quite comfortable. I spent a lot of time in Tunis taking in the sights of this large N. African city. I took advantage of this stop to visit some historical sites which the Romans had built when, in days long ago, their empire included parts of North Africa. On 21 Jan I received my posting but to my disappointment it was not to a Squadron but to the Desert Air Force Communication Flight located at Capodichino airfield outside Naples. However, at last I was getting near the scene of action which at that time was just north of Naples. Tunis to Italy was by USAF Dakota with a refuelling stop in Sicily. Bari on the Adriatic side of Italy was where we landed and the next day I arrived at my destination, Naples.

Desert Air Force Communication Flight.

The flight was under the control of the Mediterranean Allied Tactical

Air Force (MATAF) the HQ of which was located in a previous Royal

palace, at Caserta just north of Naples. The task of the flight was to

provide air transport between base areas and the forward airfields in

the operational areas.

Farchild Argus DAF Communication Flight, Naples, Italy - 1944

I think we had 2 Fairchild Argus (four seat high wing monoplane), 1 Piper Cub, (two seat very light aircraft), we also had a Boston (Twin engined Light Bomber), 1 Hurricane and 1 Spitfire but these were not used for communication purposes but were used by Staff officers from HQ for various non-operational purposes. Our accommodation was a requisitioned villa about 10 minutes from the airfield. The airmen lived in the ground floor and the Officers and SNCO’s in the top floor.

I was to spend just over 2 months with the Communication Flight in the rather mundane job of flying a variety of passengers from the base areas to forward airfields, mainly in the Fairchild and Piper Cub aircraft. I did however manage to keep my hand in by the occasional trip in the Spitfire and managed to convince the CO that although I had never flown the Hurricane it would be quite safe in my hands and I had a go. Nice to fly but I preferred the Spitfire.

Although most of the flying was pretty routine there was one occasion when nature provided an event which involved me in a not so routine flight. This was the eruption of Vesuvius in March 1944.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

For a number of days, a lot of smoke had been coming from the mountain, with loud rumbling noises, before it finally erupted and large streams of lava began pouring down the mountain side. It was an awesome sight especially at night with the lave glowing red in the darkness. There was an American airfield at Cercola, near the base of the mountain, and great concern that the lava stream might reach and overrun the airfield, so HQ decided to survey the situation from the air. I was given the job to fly an American officer over the area and after this was done he asked me to land at the airfield as he wanted to view the situation from the ground. He invited me to accompany him and we drove up the mountainside in a Jeep to a village just below the advancing lava stream. It was an awesome sight to see this huge wave of lava, about 12 feet high, dull grey on top but molten red at ground level, rolling down the hill setting alight anything which could burn and crushing everything in its path, houses included. This village was one of several which were completely destroyed.

Another flight on a Fairfield aircraft which was memorable was one, just after I had joined the Flight, where I had to fly an RAF Wing Commander to a fighter airfield on the Adriatic coast. This was a PSP (Pierced Steel Plate) strip laid parallel to and near the beach which meant there was often a strong cross wind. This was the case on this occasion and I had difficulty in keeping the aircraft straight when we touched down. I ran off the strip into the soft edging and collided with a taxiway which tore off the wheels. While the strong cross wind was a factor I must confess that inexperience on my part was the primary cause of the accident. It was most embarrassing to find out later that the Wing Commander had been sent out from the UK to investigate the high number of flying accidents in Italy and I had provided him with a likely cause. The rest of my stay on the Flight went without drama and to my delight on 10 April I was posted to the Desert Training Flight at Madna on the East coast for refresher training on Spitfires prior to going to a Squadron.

DAF Training Flight.

The task of the DAF Training Flight was to provide refresher training for pilots who had been engaged in non-operational flying since leaving their Operational Training Unit. I was at this unit for 2 weeks and my log book shows that I flew 10 hours and these hours were concentrated on battle formation tactics. On 26 April I was posted to 43 Squadron which was based just north of Naples and while this involved a ride in the back of a 3 ton lorry acr

No 43 Fighter Squadron.

The Squadron was located at a place called Lago about 30 miles North of Naples. It was a prepared metal strip of PSP and situated close to the coastline. Like all forward airfields there were few or no buildings available so we operated from tented accommodation for all activities. The nearby coastline had previously been mined by the Germans, presumably to prevent or hinder a landing by the Allies, and at that time had not been totally cleared but the army had cleared a small area of the beach so access for safe swimming was available. Apart from a limited amount of local produce, catering was the usual monotonous service rations with no variety, however someone in the cookhouse had established contact with “someone” who could supply eggs and vino for a modest price, but the problem was that this “someone” was in Bari which was a port on the Adriatic coast about 150 miles away. The problem was solved by using a Spitfire (20 minutes each way), the eggs were carried in the ammunition bays and in a small locker behind the cockpit and the vino in an external overload fuel tank. This tank, called a slipper tank was attached to the underside of the fuselage when making long flights; needless to say, a new tank was used and kept solely for the vino run. The vino run was made once a week and from memory tasted OK, not metallic in any way.

Operations.

The squadron was equipped with the Spitfire Mk9 a much-improved version

of the Mark 1 and 5 on which I had done my training. Apart from a more

powerful engine, the handling qualities were similar to previous models

and I had no difficulty converting. I had a couple of trips getting to

know the aircraft and the local area and went on my first operational

sortie on 6 May. This task was providing an escort to the aircraft of

General Mark Clark

The next two weeks involved routine patrols over and behind the front line mainly in the Mount Cassino area and providing escort to our bombers on their missions in enemy territory. These escorting missions sometime involved long flights and necessitated our aircraft being fitted with long range fuel tanks, the slipper tanks I mentioned previously. On one mission we were providing close cover while another Squadron of Spitfires which was providing top cover became engaged in a fight with 10 Focke-Wulf 190 German aircraft attempting to attack the bombers. Slipper tanks reduce the performance of the aircraft and as we were likely to become involved in the fight our leader ordered us to jettison the tanks. I had difficulty in jettisoning my tank and when I did succeed we had moved back over the top of the bombers so the tank must have dropped through the bomber formation. Fortunately it missed. We eventually did not become involved with the enemy aircraft but the other Squadron (No 92) certainly did, claiming one aircraft destroyed and seven damaged.

By the middle of May the bridgehead at Anzio had become more secure and it was decided to establish a Squadron on the bridgehead and 43 Squadron was selected. This required all the ground equipment and personnel to be moved onto the bridgehead by sea. The trucks moved to Naples on the 19th and embarked on several Landing Craft and the convoy sailed in the afternoon of the 20th May for the overnight trip. The pilots who were not flying the aircraft travelled with the ground party and I was one of them. The vessels had no accommodation so we all slept where we could, mostly on top of the equipment in the lorries. I had a rather frightening experience, for in my sleep I dreamt I was in the back of a lorry and travelling along a white dusty road, I woke up to find myself standing at the stern of the boat staring at the white wake. Needless to say, after that sleepwalk I remained awake for the rest of the night.

We arrived at Anzio the following afternoon and by evening everything was ashore and our tents set up with an obligatory slit trench alongside. The trench was necessary as the harbour was still receiving attention from the German long-range artillery and I did use it on two occasions.

Spitfire Mk IX, 43 SQN, Italy - 1944

Operations from Anzio.

Squadron activity from Nettunio strip at Anzio was similar to that when operating from our previous location at Lago i.e. Routine patrols over the battle areas in the Anzio area and over Rome. Enemy aircraft activity was slight and mainly involved attacking our bomber formations and an occasional patrol over the battle areas. On 23 May I was on an Anzio patrol when after 20 minutes my engine had a sudden drop in oil pressure and I had to return to base. Shorty after that the patrol saw one of our bomber formations being attacked by 6 enemy FW109 fighters with one bomber on fire. On sighting the Spitfires the enemy aircraft broke off their attack on the bombers and retreated North. Three of our aircraft got close enough to open fire but did not make any claim. On 29 May I was on a Rome patrol flying No 2 to the Squadron CO when, on returning to base and still over enemy territory he decided to go down to ground level to see if there was anything to shoot at. We came across a convoy of trucks and strafed them with cannon but didn’t hang around to assess the result. This was the one and only time I fired my guns as 3 patrols later my operational activities came to a halt. This happened on the 31st May.

My last Patrol

The 31st May 1944 was a beautiful Italian summer day - sunshine, blue skies and warm. I was not rostered for any flying but was on cockpit readiness at 1500 hours. I was wearing a pair of shorts and shirt under my flying overalls and a pair of ankle boots. Readiness meant sitting in the cockpit for about an hour, strapped in and ready for immediate take-off if necessary. The aircraft I was in was scheduled to be used for the 1630 afternoon patrol and just before my readiness period was completed someone advised me that the pilot rostered for the patrol was not available and I was to take his place and fly as No. 2 to the patrol leader. We took off at 1630 hours to patrol the Rome-Anzio area in a patrol of 6 aircraft but one aircraft developed an engine problem and returned to base in company with another aircraft. The remaining 4 aircraft continued with the patrol.

We were patrolling at 17,000 feet when our ground control reported that there were unidentified aircraft at 25,000 feet in our vicinity. We immediately started to climb and had reached 20,000 feet when ground control reported that the aircraft had now been identified as enemy aircraft. Another Spitfire squadron patrolling in an adjacent area called and asked if we wanted assistance and our leader asked them to stand by. We had just completed a turn to Starboard and I was on the left side of the formation flying line abreast which enables each pilot to have a view of the other pilot’s blind spot, his tail area. I’ll stop my narrative at this point and show what was written in the Squadron Operation Record Book about the patrol:

My observation on this entry in Squadron records is that I have no recollection of another Spitfire squadron bouncing our patrol, so it must have occurred after I was shot down. I’ll return to what happened to me.

After completing our turn, I was momentarily distracted by a bright flash on the ground, far below, then I looked over my right shoulder and there was a Messerschmitt 109G at very close range with his guns firing, as I saw the flashes from the tracer ammunition. I immediately took evasive action by turning into the attack (the recommended action) by applying full aileron and pulling back hard on the control column. The turn was so tight that I momentarily lost my vision because of the G force and when I regained my sight the aircraft was inverted and in a dive. I think that what had happened was that the turn was so tight that it caused a high-speed stall causing the aircraft to flick roll. I can’t remember if I was aware of the cannon and bullet shells hitting the aircraft but when I looked at the Starboard wing there was a huge hole just forward of the aileron. What other damage had been done I don’t know but the aircraft was in a spin and I was having difficulty in regaining control, possibly because of other damage. I remember thinking that the enemy aircraft was still on my tail but now, on calm reflection, as my aircraft was in a spin this was an irrational thought. However at this stage self-preservation instincts became paramount and I decided to bale out. I pulled back the cockpit canopy and stupidly pulled the locking pin of my cockpit harness before disconnecting the radio and oxygen leads to my helmet and mask.

From that moment on I don’t know what happened, but it was sudden mayhem. I was conscious of tremendous noise and being thrown around for what seemed a long time before there was sudden calm and I remember thinking that I was dead and amazed that there had been no pain involved. I don’t know how long the period of calm lasted but the next thing I remember was being aware that I was free of the aircraft and falling. I remember grasping the ripcord of my parachute but don’t remember pulling it. I obviously did for above me was my opened parachute and all was quiet once more. I had no helmet and had lost my right boot but was otherwise intact, or so I thought. Now to explain what I think happened.

When you have control of the aircraft and in reasonably level flight the recommended method of bailing out from a Spitfire is to disconnect helmet leads, undo the harness and dive over the side onto the wing. Another method is to trim the aircraft nose heavy, keeping level by holding back the control column, then undo your harness and leads and release the control column, the aircraft will then dive sharply and you will be catapulted out of the cockpit. However, in my case the aircraft was in a spin and when I released the harness locking pin I must have been partially or fully thrown out of the cockpit, In the process my helmet, with attached mask was dragged from my head cutting off my oxygen supply. The sudden loss of oxygen must have caused a short period of unconsciousness, hence the period of calm. How long it lasted I don’t know but it must have been only a short period for by this time I was probably below 20,000 feet and getting sufficient oxygen from the surrounding air, enough for me to regain consciousness and resort to my parachute.

What height I was at when I opened my ‘chute is only a guess but I think it would have been about 12,000 feet and looking down I saw my aircraft hurtling to the ground trailing smoke, so the engine had probably been hit during the attack. I realised that the aircraft was heading for a large lake and shortly after saw it hit the water with a large splash. It dawned on me that I was also above the lake and that was where I was heading.

I remembered being told during my training days that you could control

your direction in a limited way by pulling on the rigging lines. I tried

to move to the right by pulling the rigging lines but this only

increased the rate of descent and started an oscillating swing. I gave

this up and prepared for the

On stepping ashore, I found that I couldn't stand on my left leg and had

to be helped by the old man. Just then a small group of German soldiers

burst out of the bushes, led by a burly Sergeant who stuck a machine

pistol in my stomach and shouted something which I didn't understand but

presumed to be "hands up". I was standing on one leg, dripping wet, had

no weapon and not feeling very heroic, so I complied. With the old man

still helping me I was escorted to the nearby road and put into the

sidecar of one of several motor bikes and taken to a small town at the

North end of the lake. I was put into a room and all my clothes removed.

The room had no furniture but there was a pile of grass or straw in one

corner which I lay on for a while until the Germans returned with my now

dry shorts and shirt but no flying overalls. I was then taken somewhere

and a doctor examined my leg, encased it in a splint and indicated that

it was broken just above my ankle. This must have occurred during my

exit from the cockpit but I was unaware

Later that night, under the cover of darkness, I was taken to a large hospital in the town of Tivoli, east of Rome. The move took place at night because during the day the Allied aircraft strafed anything that moved. I was in a large ward with all the German wounded and one of the staff members spoke English. When he realised that I was a pilot he mentioned that there was another prisoner, also a pilot, in the ward below mine. On the pretext of going to the toilet I managed to hop down the stairs and located this unknown pilot. To my great surprise it was Warrant Office Saville a New Zealander from my Squadron who had been on the same patrol as myself. He was badly wounded, with his head covered in bandages, but he related his story. He had been jumped by the same flight of German aircraft that got me and had been hit in the engine. He couldn't make it back to our lines and crash landed in a field. The aircraft burst into flames on landing and he was quite badly burned. He was rescued by some Italian civilians and taken to their farmhouse. However, the Italians could not treat his burns and sought the help of the Germans. He was put into a kind of ambulance and on the way to a hospital the vehicle was strafed and he got a bullet wound in the head. I only had time to give him a brief outline of my situation before I was taken back to my ward.

The following day the Germans began evacuating the hospital and all the walking wounded and the less seriously wounded were assembled and loaded on to an assortment of vehicles. I was placed in a small bus along with a number of Germans and the convoy set off late at night under the cover of darkness, heading north. We had been travelling for a few hours when the convoy was attacked by an Allied aircraft which had dropped a parachute flare. There was great confusion and my fellow travellers evacuated the bus in great haste or as fast as their wounds allowed, I followed. I hopped into a roadside ditch and watched as the aircraft dropped another flare and attacked vehicles near the head of the convoy. The attack was over in about 10 minutes and as far as I was aware only one vehicle was destroyed. In the confusion and darkness, I felt sure that my presence would not be missed if I remained in the ditch when the Germans got back on the bus and I seriously considered doing so. However, being far from mobile the risk of recapture was high, so I decided to stay with my captors, become more mobile and hope that the future might present another opportunity.

The convoy destination turned out to be a hospital In Perugia and after a night stop there I ended up in a hospital in Florence for two days. By this time, I had been joined by several Army prisoners who were also semi mobile. We were all confined to a large room and among the Army prisoners was an Indian Army Sikh who still had his head covered in the Hindu fashion. I felt sorry for him for when we were given food, delivered in a large wooden tub and consisting of a kind of soup with vegetables and meat, he refused to eat it. The poor chap was starving but because of the meat content he refused to eat. I well remember my stay in this hospital for the day we left was the 6th June and we heard that the Allies had landed in Normandy. This was great news but I remember the German guards indicating to us that the Allied forces would soon be trapped and eventually thrown back into the sea.

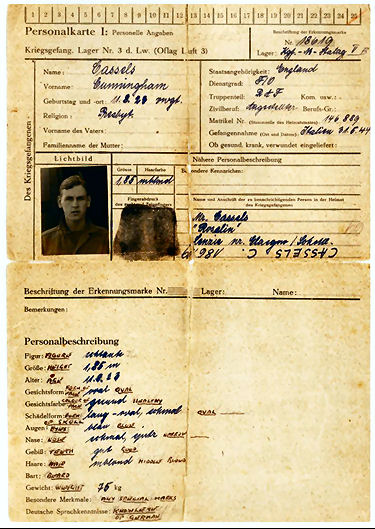

Another lorry journey 100 miles north and I arrived at a large hospital at Mantua in Northern Italy where I stayed for 10 days. Here the conditions were more civilised with a comfortable bed in a large ward. It was here that I was interrogated by a member of the Luftwaffe. He spoke very good English and told me he had lived in England for a few years before the war. He asked me the usual questions - what aircraft I was flying, what Squadron I came from, where the Squadron was located and other military matters. He then went on to ask details of my family – mother’s maiden name, where I was born, my civilian job and other personal details. I refused to answer these questions and told him that I was only obliged to give my service number, rank and name. He then said that some POW's were more co-operative and showed me a form signed by an American bomber pilot which gave details of his target, bomb load and squadron details.

I remember thinking at the time that that USAF pilot was a little too co-operative. A little later he produced a form with a large red cross and said that he had to fill in this form so that the Red Cross would notify my parents of my capture. Against the questions on the form, some of which had no connection with the Red Cross activities, he wrote "declined to answer" but it listed my number, rank and name. He showed me the form and said I had to sign it. Stupidly I did. He then pointed to my personal Rolex watch and said that he would have to take it from me. His friendly attitude suddenly changed and became quite aggressive. Not knowing whether he had that right and not being in a position to argue I gave it to him. He then said that he knew quite a bit about me and proceeded to tell me that I had been flying a Spitfire belonging to the "Black Falcon" squadron (the squadron mascot was a fighting cock), the name of the Commanding Officer and that we were based on Anzio. He may have had other information but he didn't disclose it. When the interrogation was over and I had returned to the ward I suddenly realised that the information he had about me would be transferred to another form with my signature and shown to other air force prisoners and they would brand me as a big mouth. I take comfort in knowing that he got nothing from me that he didn't already know, but kick myself for signing.

To Germany.

On 18th June I was loaded onto a hospital train bound for Germany. There was a separate carriage for the POW wounded some of whom were like me, walking wounded. The carriage was like a dining car with beds replacing the table and chairs. One chap, I think he was RAF, whose wounds were in his upper body but who was quite mobile, decided to make a break when the train was near the Swiss/Italian border. In the middle of the night when the train had slowed down to a near walking pace and the guard was either absent or asleep, with the help of a colleague he got the door open and disappeared. I'll never know whether or not he made it; I hope he did. We crossed the Brenner Pass and arrived in Munich on 20th June and the same day travelled to Rottenmunster Hospital in Rottweil Germany.

Rottweil is located in South West Germany, approx. 130 miles west of Munich, 50 miles south of Stuttgart and only 40 miles north of the Swiss border. Rottenmunster was a large hospital with several floors and part of one floor was allocated to hospitalised POW's. I was in a room with six other officers - 3 British Army, 1 Australian Army l American Air Force and 1 Rhodesian Air Force. We were all in the convalesce stage and were not confined to bed. The inactivity was quite boring and only two events come to mind worthy of recalling. The Australian (Bob) had been captured in Egypt in 1941 and had been in a POW camp in another part of Germany. He was sent to Rottenmunster to have an operation for haemorrhoids which was performed by a British doctor, also a POW. When he came back to the room he was not his usual jovial wisecracking self and that night I was awakened by him shouting "Jock Jock get the doctor". Apparently he had had a tube inserted in his rectum acting as a drain and in his sleep he had pulled it out. I went along the corridor and woke up the doctor who in a somewhat irritated voice said that he was to put it back. I won't repeat his exact words but you can imagine what they were. Anyway, I relayed the message and went back to bed leaving Bob moaning about medical incompetence. The following day when things had calmed down and the matter was being discussed Bob told me that he had been dreaming that he was escaping and had just reached the barbed wire when a guard armed with a bow and arrow shot him in the bum. Naturally he pulled it out but unfortunately it wasn't an arrow.

The next event of significance in this hospital was my 21st birthday on

the 11th August. Bob, the Aussie, decided that it was an

event to be celebrated. Without my knowledge he got the others to

contribute some elements of their Red Cross parcel and somehow contacted

the hospital

It was now well into August, my leg had healed and as I had been mobile for some time I was awaiting transfer to a POW camp. This happened on 25 August when my escort, two German soldiers, arrived and took me to the local railway station. Our destination was Stalag Luft 3 which was located several hundred miles to the East on the German Polish border, a considerable distance away. At this stage my only clothing was still the shorts and shirt I had been wearing when I was shot down but before leaving I was given a British Army Khaki uniform (provided by the Red Cross). I was thankful for this uniform for when we travelled through the city of Stuttgart, which had been bombed 2 days earlier, the German passengers in the carriage were obviously questioning my escort about their prisoner. I'm sure my escort thought I was a soldier and I was glad I wasn't in an Air Force uniform for German civilians weren't kindly disposed to "Terror Fleigers", as the Bomber crews were called. It was a tedious journey involving a night stop at Leipzeg where I was put into the station jail which I had to share with rats. My request to be moved somewhere else was refused. On the 27th August I arrived at Stalag Luft 3 to join several thousand other Air Force prisoners.

Stalag Luft 3 - Sagan

POW Identity Card Stalag Luft 3 - 1944

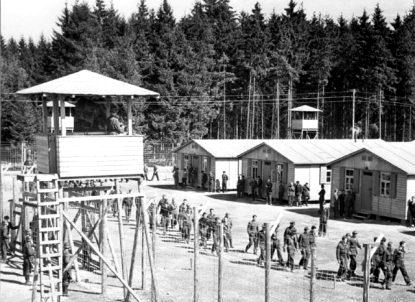

Luft 3 was a huge camp consisting of 5 compounds named North, South, East, West and Centre. The South, West and Centre compounds housed American airmen and the North and East housed British airmen. There was another overload compound a few miles away from the main camp named Belaria which had a mixture of inmates.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The main camp was located in a pine forest near the town of Sagan. The camp was the venue for several escapes but the major one was "The Great Escape" from the North compound which resulted in the murder by the Germans of 50 prisoners. But that is another well documented story.

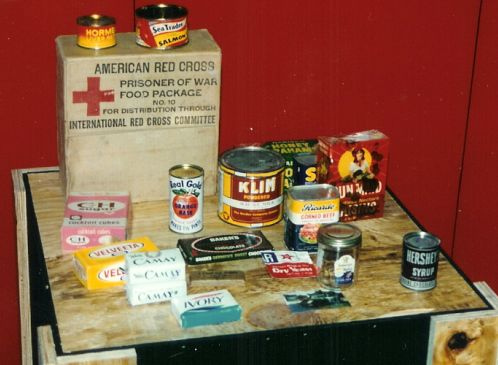

I was sent to East compound which had six huts with 12 rooms in each hut. My address was Room 5 Hut 69. There were 11 officers in the room, 7 RAF and 4 RCAF. We slept in 2 tier bunks with wooden boards and a straw paillasse as mattress. The room was 16 x 24 feet with a stove in one corner for heating. A corridor ran down the middle of the hut with a night toilet at one end and a small kitchen at the other. The room organisation was that each man had a domestic duty to perform, some internal and some external. My job was to get up early and go to the kitchen and cut our German black loaf of bread into eleven equal slices. Sounds easy but the loaves sloped at the ends so the end slices had to be a little bit thicker so everyone got an equal portion. As prisoners we were entitled to the same rations as a German soldier but it never worked that way, usually much less. Each man was entitled to be issued with a weekly Red Cross food parcel but in my time the issue was down to one parcel to two men and later this was reduced further. This was because the Germans had difficulty in transporting the parcels from the main Red Cross depot in the North to the various camps throughout the country. The reason for this was the disruption caused to the railway system at that stage of the war by the Allied bomber and fighter aircraft.

In East Compound there were around 800 prisoners from a huge variety of peacetime civilian occupations so there was a vast amount of skills available for camp activities and these skills were put to good use in alleviating the boredom of prison life. For example, debates, lectures, study, theatrical plays, handiwork classes, sporting activities, to name a few. A lot of the necessary equipment for these pursuits was provided by the Red Cross, all of course vetted by the Germans. The prisoners made a 9 hole chip and putt golf course in the sandy soil around the inside perimeter of the compound. A few clubs were provided by the Red Cross but shortage of balls was a problem so they were made from pieces of rubber inside a leather skin. No greens of course!

Generally the authority of rank was never used in the camp as prisoners considered themselves as just prisoners, however the senior ranking officer assumed responsibility for all prisoners when dealing with the Germans. He had the title of Senior British Officer (SBO) and performed the role of a Commanding Officer for the prisoners. He would co-ordinate the activities of selected officers who had the task of organising various camp activities. One of the more important responsibilities was that of security, and he and his committee would interview and interrogate all new arrivals to ensure that they were not impersonators planted by the Germans. Any plans to escape had to be vetted by both the SBO and the escape committee and help and assistance would only be provided if the plan was considered viable. Apart from the guards manning the towers on the perimeter with their guns and searchlights the compound was patrolled by Germans in overalls whose job was to roam the compound looking for any signs of escape activities. They were named "ferrets" as they would often hide and crawl under the huts, keeping a close watch on the prisoners’ movements. Every morning and evening we were paraded for the daily roll call. We formed up by hut numbers in rows 5 deep which facilitated the counting process. In addition to the daily counting we were occasionally subject to a "picture" parade when our identity was compared to the photo taken when we arrived in the camp.

Naturally we were constantly wondering how the war was progressing, particularly as at that time the Russians were making advances on the Eastern front and the Allies had landed in France. The German papers we managed to obtain did give us an inkling that the Germans were on the back foot. However, unknown to the Germans we had our own source of information. This was a radio which was cleverly concealed in a false compartment on the underside of a table. More about that table later. I don't know how the radio was made but the ingenuity of our expert prisoners knew no bounds and by bribing and eventually threatening the "ferrets" the key components such as valves and other necessary bits and pieces were obtained. The method was to cultivate a few "ferrets" who had a liking for the chocolate and cigarettes in our Red Cross parcels and persuade them to brings in a few innocuous items in exchange. Once this had been done the threat of exposure to their superiors was such that the necessary key components were obtained.

Our news was obtained via BBC radio broadcasts and the person who manned the receiver would visit the huts the next day and verbally pass on the information. One day, during a picture roll call, the Germans did not have their portable table with them so they went to a room and brought out a table. The roll call was completed without incident but little did the Germans know that it was the special table and that our radio was within inches of their hands. I believe there was another source of information; this was a coded link to some authority in the UK, I think it was the Air Ministry, and this was done through letters to prisoners but I am unaware of any details - it was not general knowledge. It was through this means that after the Great Escape in March and the favourable progress of the war that escape attempts were discouraged. Just after the Great Escape and the murder of 50 prisoners, the Germans had issued a pamphlet headed "Escaping is no longer a Sport" - briefly is said that any prisoner caught after escaping would be considered a saboteur and shot. At this stage there was general optimism that the Allies were winning and as far as I am aware there were no more attempts to escape.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

As Christmas 1944 was approaching most rooms managed to save a few items of food so that we were able to celebrate Christmas with a few extras on the table while thinking of our loved ones having their Christmas dinner thinking of us. Our Christmas present was the air of optimism in the camp that the New Year would bring release and our return home. While inside the huts didn't look very seasonal the weather outside certainly did. with the camp covered in snow. By mid January 1945 we could sense that something was about to happen and we could only guess that it had something to do with the Russian breakthrough on the Eastern front. On 27th January we found out, when the Germans announced that the camp was being evacuated and we had to prepare for an immediate march.

The March

On being informed early on the 27th January of the evacuation, the camp

became a hive of activity, with prisoners making rucksacks and sledges

from whatever materials they could find. The Germans surprisingly

produced enough RedCross parcels for an issue of one per man and what

food

There were a few horse drawn wagons in the column loaded with the guards equipment and rations. We had to make do with what food we took with us from the camp. From a high point on the march the column looked like a black snake stretching from horizon to horizon against the snow covered landscape, not surprising as there were several thousand prisoners in the column. We marched all day and stopped at a place called Halbau where we were accommodated in a school for 2 nights sleeping wherever we could find a space - on desks, chairs but mainly on the floor.

Another all day march on the 30th Jan and another night accommodated in

a school at Liebe. The next day the march ended in a factory at a place

called Muskau. It was here that we managed to get reasonably warm, for

the factory furnaces had only recently been shut down and there was

plenty

Stalag 111a – Luckenwald.

On 4th February, 1944 we marched the short distance from the station to the camp where we were herded into a large building containing communal showers - and did we ever need a shower. The water wasn't very hot but it was heaven to be clean again. By late evening we were located in our accommodation which, compared to that at Stalag Luft 3, was very basic. Our living quarters were in large huts, not divided into rooms but with the open space filled with three tiered wooden bunks and brick flooring. I don't know who the previous occupants were but the huts were not very clean. It was a big camp with a large population including a lot of Polish and Russian prisoners. Food became a problem, or lack of it did. There were no Red Cross parcels and the food we got from the Germans was very basic - potatoes and soups made of cabbage and other unidentified things were the main items of sustenance. We were constantly hungry and I remember making a habit of eating the potato skins discarded by the others, to assuage my hunger. It wasn't much help but it was something to chew on. Life was very different from that in Stalag Luft 3, no activities to stimulate the mind and keep the body active, just dull and monotonous living. The only bright spot was the thought of release which now appeared a distinct possibility - but when?

On 12th April we were again marched to the local railway where a long line of covered wagons (cattle trucks) awaited. We were loaded into the wagons as before but after a few hours with no movement we detrained and waited beside the wagons. It soon became obvious that we weren't going anywhere for there was no locomotive to pull the train. We were told that an engine would be arriving later that day. In the meantime we asked the Germans to paint a large Red Cross emblem on the top of the train to prevent a possible strafing attack by Allied aircraft. This wasn't done.

We remained at the station until the next day when, as no engine had arrived, we were marched back to the camp. By now it was obvious from the behaviour of the guards who were, in the main, quite old men that something was about to happen. One night an aircraft, presumably Russian, strafed some target near the camp and had us all ducking for cover. A few days later on the 21st April we woke up to find that the guards had vanished during the night and the camp was now unguarded. But not for long, for next day on the 22nd April several Russian tanks arrived, one tank demolishing part of the barbed wire fence to the cheers of the POW's. As they were part of the Russian forces attacking Berlin and we were in the midst of a battle area we were told to stay put and await further instructions. A couple of days later the follow up troops arrived and this time we were guarded by the Russians who were under instructions to keep us secure. We all had our opinions as to how and when the Russians would transfer us to the Americans who had stopped their advance Eastwards at the river Elbe which was about 30 miles to the West of the camp. All we knew for certain was that the Russians intended to keep us in their hands until they decided on our future.

On the morning of the 7th May an American officer arrived in a Jeep, presumably to discuss with the Russians our evacuation, but the Russians told him that they were not prepared to release us as the decision would have to be referred to higher authority. The American officer left, but before he did he mentioned to one of our senior officers that he had brought with him six American trucks which were waiting in a wood near the camp. When I heard this news I spoke with a colleague and we decided to try and get to the trucks. We got through a hole in the wire at the back of the camp and made our way, along with many others, to the wood which was about a mile from the camp. When some distance from the camp we heard rifle fire and later found out that the Russian guards were shooting over the heads of escaping POW's to try and deter them. However, we were out and eventually found the trucks and a large African American Sergeant who greeted us with words which I will never forget "Come on you guys, get your arse into gear we wanna to get outta here". Of course so did we.

The first two trucks were already full and had left and we got on the third truck and soon were on our way to the River Elbe. We arrived at the river where a pontoon bridge had been erected at a place called Wittenberg, with the Russians on the East side and the Americans on the West. The Russian soldiers waved at us as we drove onto the pontoon bridge and the American soldiers did likewise when we drove off. It was mid-afternoon on the 7th May 1945 and I was FREE. However, only three trucks got across. When the Russians at the camp realised what was happening they communicated with the soldiers at the bridge to stop the trucks crossing. The last three trucks were stopped and their load of POW'S returned to the camp. It was to be another 3 weeks before the Allies managed to negotiate with the Russians to release the many thousands of POW's in the camp and I understand politics at a high level was involved.

When we got over the river the trucks continued for about 30 miles on to Schonebeg where a large camp had been set up to process released POW's. Our first meal was a bit of a surprise for while we had dreamed of this moment and of the huge amount of food we would consume we were served very small portions. Apparently, this was for medical reasons, as having had little food, both in quantity and quality, for several months a large nutritious meal would have been detrimental to our health. While in the Dining Hall I heard, for the first time, the loudspeakers playing a popular Bing Crosby song “Don't Fence Me In”. How timely!!

However, that was really of no importance for the next day on the 8th May 1945 it was announced worldwide that Germany had capitulated and the war in Europe was over. The next move, on the 11 May, was another lorry trip of 60 miles to Hildesheim where after a night’s stop we were flown to Brussels. It was during this flight that we saw the result of the Allied bombing of the industrial cities of the Rhur - city after city absolutely devastated. A night stop in Brussels then onto an RAF aircraft which took us to RAF Wing, an airfield North West of London where, immediately on landing, we were lined up and deloused before showering. This was 13th May 1945 and 3 years and 1 month had elapsed since departing from the UK on the troopship from the Clyde on 16 April 1942. The next 2 days involved Administrative details, issue of new uniforms and getting settled back into Service life. We were also interrogated regarding our period in captivity, particularly in regard to aircrew who were still listed as missing and of whom the RAF and the Red Cross had no information. I also managed to 'phone home and let my family know that I was back in Britain. I was given indefinite leave and a night journey in a very crowded train saw me arrive in Glasgow on 16 May to be met by my father and brother Jim who had just returned from 4 years’ service with the Army in the Middle East. A large gathering of family at my grandmother’s house greeted me and I knew I was home. After a few days, while I was delighted to be home, I had a strange feeling of being unsettled and would often seek solitude in the garden. I can't really describe what the feeling was but it lasted for a few weeks before I really got round to accepting my new situation and change of lifestyle. It was a period of strange personal emotions.

Jock’s story will continue next issue.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A sign used in Australia indicating that slow drivers are about to increase their speed. |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Click here to go to part 2 of Jock's story:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

frustrating period for we had nothing to do but wait for the next

move i.e. to an Operational Training Unit (OTU). I spent this time

hitching lifts to Ismailia, about 20 miles distant to alleviate the

boredom and keep in touch with civilisation. Part of the road to Ismailia ran beside a canal known as the Sweet Water Canal but I’m sure

that wasn’t the proper name but was one given to it by the occupying

British forces for it stank to high heaven. Fortunately, the camp was

located near the Cassareep airfield which had a cinema so we made good

use of that facility. Nevertheless, it was a trying period of two months

of idleness which I could have done without. However, it did come to an

end when I was posted to No. 73 OTU on 2nd October 1943.

frustrating period for we had nothing to do but wait for the next

move i.e. to an Operational Training Unit (OTU). I spent this time

hitching lifts to Ismailia, about 20 miles distant to alleviate the

boredom and keep in touch with civilisation. Part of the road to Ismailia ran beside a canal known as the Sweet Water Canal but I’m sure

that wasn’t the proper name but was one given to it by the occupying

British forces for it stank to high heaven. Fortunately, the camp was

located near the Cassareep airfield which had a cinema so we made good

use of that facility. Nevertheless, it was a trying period of two months

of idleness which I could have done without. However, it did come to an

end when I was posted to No. 73 OTU on 2nd October 1943. rear seat to simulate this reduced visibility. It

didn’t take long to advance to the stage when I was ready to fly the

famous Battle of Britain fighter, the Spitfire. After my back-seat test

in the Harvard by the Chief Flying Instructor, Squadron Leader Neville

Duke, himself a Battle of Britain ace, I had my first Spitfire flight on

October 18.

rear seat to simulate this reduced visibility. It

didn’t take long to advance to the stage when I was ready to fly the

famous Battle of Britain fighter, the Spitfire. After my back-seat test

in the Harvard by the Chief Flying Instructor, Squadron Leader Neville

Duke, himself a Battle of Britain ace, I had my first Spitfire flight on

October 18.

As the distances weren’t great and the forward

airfields were usually the small airstrips used by tactical fighters,

the flight was equipped mainly with small single engined aircraft.

As the distances weren’t great and the forward

airfields were usually the small airstrips used by tactical fighters,

the flight was equipped mainly with small single engined aircraft.

the Commander of the Allied forces who was visiting his forces on Anzio

bridgehead. In January 1944 the Allies had made a landing on the coast

at Anzio just 40 miles SW of Rome and had established a bridgehead

extending a few miles inland before being contained by the Germans.

After the bridgehead had been made secure a landing strip was

constructed at a place called Nettuno and by April was used by fighter

aircraft as an advanced airfield. However, being so close to the enemy

front line and subject to their artillery fire it was only used during

daylight hours, aircraft withdrawing to their main base at night.

the Commander of the Allied forces who was visiting his forces on Anzio

bridgehead. In January 1944 the Allies had made a landing on the coast

at Anzio just 40 miles SW of Rome and had established a bridgehead

extending a few miles inland before being contained by the Germans.

After the bridgehead had been made secure a landing strip was

constructed at a place called Nettuno and by April was used by fighter

aircraft as an advanced airfield. However, being so close to the enemy

front line and subject to their artillery fire it was only used during

daylight hours, aircraft withdrawing to their main base at night.

inevitable. The procedure for entering the water in a parachute is to

release yourself from the parachute a few feet above the water so that

you don’t go under with the “chute” still attached. It was a calm day

and the surface of the lake was like glass so I had difficulty in

judging my height. When I decided it was time I hit my harness release

but I obviously didn’t hit it hard enough and went into the lake still

attached to the chute. My life jacket (Mae West) brought me back to the

surface and I managed to free myself from the harness but the rigging

lines had fallen on top of me and I was having difficulty in freeing

myself. It was then that I noticed a small rowing boat with 2 people

heading towards me. They grabbed the floating parachute and pulled me,

still attached to the rigging lines, towards the boat. I got rid of the

lines and with difficulty managed to climb aboard. My rescuers were an

elderly couple, man and wife, and in my pidgin Italian I asked them if

there were any Germans in the area. They replied in the negative but as

I was shortly to find out, what they thought I had asked them was

whether they were Germans.

inevitable. The procedure for entering the water in a parachute is to

release yourself from the parachute a few feet above the water so that

you don’t go under with the “chute” still attached. It was a calm day

and the surface of the lake was like glass so I had difficulty in

judging my height. When I decided it was time I hit my harness release

but I obviously didn’t hit it hard enough and went into the lake still

attached to the chute. My life jacket (Mae West) brought me back to the

surface and I managed to free myself from the harness but the rigging

lines had fallen on top of me and I was having difficulty in freeing

myself. It was then that I noticed a small rowing boat with 2 people

heading towards me. They grabbed the floating parachute and pulled me,

still attached to the rigging lines, towards the boat. I got rid of the

lines and with difficulty managed to climb aboard. My rescuers were an

elderly couple, man and wife, and in my pidgin Italian I asked them if

there were any Germans in the area. They replied in the negative but as

I was shortly to find out, what they thought I had asked them was

whether they were Germans. of it happening because of the mayhem of the situation. Later that

afternoon I was moved to a large country mansion which had been

converted to a sort of convalescent home for recovering wounded

soldiers. I had 5 German paratroopers for company in the room and

although I couldn't understand what they were saying I gather they were

expressing a certain amount of sympathy. A little later I heard the

noise of aircraft and hopped to the window to have a look. It was a

flight of aircraft at great height and was obviously from my Squadron,

carrying out the last patrol of the day. Observing this the Germans

laughed and from their gestures and the use of the word "Kamerad"

pointed out that I would not be returning home with my "Comrades" that

night. As if I needed reminding.

of it happening because of the mayhem of the situation. Later that

afternoon I was moved to a large country mansion which had been

converted to a sort of convalescent home for recovering wounded

soldiers. I had 5 German paratroopers for company in the room and

although I couldn't understand what they were saying I gather they were

expressing a certain amount of sympathy. A little later I heard the

noise of aircraft and hopped to the window to have a look. It was a

flight of aircraft at great height and was obviously from my Squadron,

carrying out the last patrol of the day. Observing this the Germans

laughed and from their gestures and the use of the word "Kamerad"

pointed out that I would not be returning home with my "Comrades" that

night. As if I needed reminding.

kitchen to put the ingredients together in the shape of a cake. On the

afternoon of my birthday he produced a cake of somewhat small

proportions, approx 5 inches in diameter, covered in some sort of white

stuff like icing. There was no decoration, only 2 chocolate coloured

balls on top. There was a little accompanying note which read "Happy

Birthday Jock - they drop today" The cake was divided into 6 slices and

we all agreed that it was a great treat under the circumstances. It was

a simple little party but one which left an everlasting impression in my

mind. That wasn't the finish, for he somehow conveyed to the kitchen

labourers (Russian POW's) that a little gift would be appropriate. They

produced, from scrap wood, a little wooden duck suitably painted, with

wheels connected to wings which moved up and down when pushed along the

ground. There was a long stick attached and later that day I did several

circuits of the small exercise yard pushing the duck, cheered on by my

roommates and to the merriment of several of the Russians. I'll never

forget my 21st birthday nor the kindness, generosity and thoughtfulness

of my fellow prisoners of war.

kitchen to put the ingredients together in the shape of a cake. On the

afternoon of my birthday he produced a cake of somewhat small

proportions, approx 5 inches in diameter, covered in some sort of white

stuff like icing. There was no decoration, only 2 chocolate coloured

balls on top. There was a little accompanying note which read "Happy

Birthday Jock - they drop today" The cake was divided into 6 slices and

we all agreed that it was a great treat under the circumstances. It was

a simple little party but one which left an everlasting impression in my

mind. That wasn't the finish, for he somehow conveyed to the kitchen

labourers (Russian POW's) that a little gift would be appropriate. They

produced, from scrap wood, a little wooden duck suitably painted, with

wheels connected to wings which moved up and down when pushed along the

ground. There was a long stick attached and later that day I did several

circuits of the small exercise yard pushing the duck, cheered on by my

roommates and to the merriment of several of the Russians. I'll never

forget my 21st birthday nor the kindness, generosity and thoughtfulness

of my fellow prisoners of war.

there was in each rooms’ cupboard was shared among the occupants. The

bitterly cold weather was a problem and prisoners donned as many items

of clothing they could. I managed to make a sort of rucksack to carry

what little possessions I had but for warm clothing I only had an RAF

airman’s greatcoat (issued by the RedCross) and my Army battledress

which proved insufficient for the conditions, consequently my march was

a very cold one. We left the camp in the early hours of the 28th January

with the guards spaced at intervals on either side of the column walking

with us and feeling the cold as much as we were.

there was in each rooms’ cupboard was shared among the occupants. The

bitterly cold weather was a problem and prisoners donned as many items

of clothing they could. I managed to make a sort of rucksack to carry

what little possessions I had but for warm clothing I only had an RAF