|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

My Story.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Contents.

|

||

|

|

||

|

I was born into a military family, but an Army one. My father was an artillery officer and I spent my childhood moving in the triangle of Sydney, Queenscliff, Brisbane, with Canberra thrown in for good measure. Seven schools in all, in four different States. I was once kept in over lunchtime by the nuns for not have the appropriate “loop” in the cursive letter “f”. The differences in education systems were so stark that I ended up finishing Year 12 at 16yrs old. With no concept of what I wanted to do with my life I decided a law degree sounded at least interesting and enrolled at the Australian National University in Canberra.

My entry to the Air Force happened almost by accident. I had been working as a law clerk during my study and discovered it was possibly going to be the most boring job ever. Then I found out that Air Force and Navy were offering undergraduate places where they would actually pay me to go to university! It seemed too good to pass up. I applied for both; Air Force was faster in the recruitment process and here I am!

The start was a bit rocky. I remember going to my ‘knife and fork’ course in my first year as an Officer Cadet. I had just got married and changed my last name. Because my marriage was so new, my name was wrong on the course roll. 1997 Air Force solution: I was to revert to my maiden name to make it easier for the staff! When I eventually got to Officers Training School at Point Cook two years later in 1999, they at least acknowledged my name! We were a course of 43, with 38 men and 5 women, so they put us in 5 sections with one female in each. I never was much of a runner, so my poor section was always in trouble in the sports challenges. However, we came to a pretty good arrangement – they spit polished my shoes and taught me sword drill, and I fixed all of their written assignments. And I blitzed the section vs section debating challenge. Teamwork.

After a year in Canberra, I was off to my first Base. Offered a choice of Tindal, Townsville or Wagga, I chose Tindal – figuring I would never get to see that part of the world otherwise. Travelling to my new posting with a six week old baby, my travel was booked by air to Darwin and then for some reason they booked me on a bug smasher from Darwin to Tindal. It was wet season and there was a thunderstorm in full force. The turbulence was phenomenal. The lady in front on me was popping Valium and the helpful conversation behind me went: “This is just like that movie 6 days, 7 nights” and his colleague, “Isn’t that the one where the plane crashes”……..

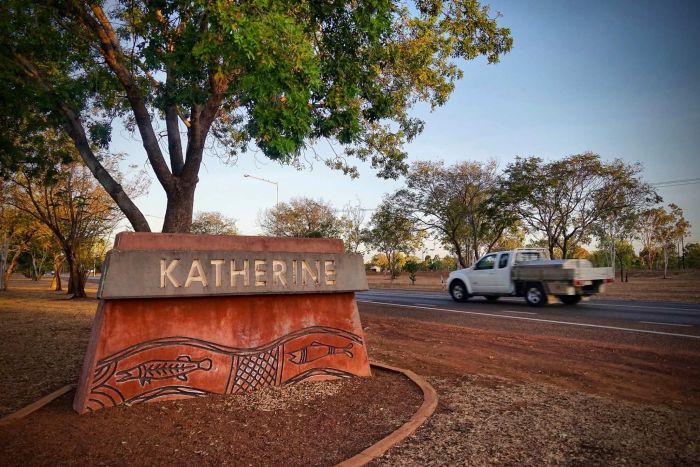

Arriving in Katherine, I had never seen such rain. All day and all night, and when it stopped people ran out of their married quarters, started up their lawn mowers and cut the grass before the next downpour. We had green frogs in the toilet, tiger snakes in the backyard and they had to stop people jogging on the fire trails around the base after someone was mauled by a buffalo. For this city girl it was a shock.

The posting itself was fantastic. A brand new FLTLT, with not a clue, the only legal officer on Base, paired up with an ex-Rhodesian Warrant Officer Disciplinary, Ray Woolnough (latter WOFF-AF), who helped me and messed with me in equal measure. Discovering that drill was not my forte, he quickly assigned me as FLTCDR for every Base Parade so that I could “practice” and he could laugh at me.

75 Squadron was led at that time by then WGCDR Mel Hupfeld (later Air Marshall). I will always be grateful for him allowing this baby legal officer to understand the workings of an operational squadron and set me up for the future.

Tindal by that stage was trying to shake off its frontier-town image in favour of the modern Air Force. We were doing a pretty good job at being family friendly. On mixed dining-in nights we would have a line-up of prams with sleeping babies in the corridor outside the room and I remember one night when the assigned reserve legal officer didn’t show up for after-hours legal aid appointments, so I did them with my seven month old son crawling around on the floor underneath the desk….

Next up was Amberley, where I was posted to Headquarters Combat Support Group.

It was late 2002 and the Air Force was gearing up for the longest deployment period in its history. In those early days it was all very uncertain. Amberley was a staging point and I was required to brief the departing squadron on the rules of engagement (ROE). The only problem was that the ROE were still compartmented, which meant I wasn’t permitted to see them. I literally received the document 10 minutes before the personnel were due to depart and delivered the brief on the tarmac. Luckily, I had taken a “best guess” of what the document might say and prepared that – so I just needed to confirm and make small changes.

We were working closely with the Americans, for the first time in many years and I was sent to the US to work on a project with the US Army, to capture legal lessons learned from Afghanistan and Iraq operations about working in a coalition. I was fortunate enough to do this work from the beautiful University of Virginia campus and my work was published that year. It was essentially about learning the legal and political limitations of each of our partners, so we could then conduct operations more smoothly.

The most memorable conversation I had during that time, was during a discussion with my US colleague about negligent discharge of a weapon. In the ADF then, as now, if you negligently fire a live round on operations you will be charged due to the seriousness of the event. The US Army charged only sometimes and I was enquiring as to their reasoning. The Captain solemnly explained, “Well one of the key things we look at is if they have ever been trained on the weapon….”

Back in Australia for 10 days, I then deployed to the Air Task Group in the Middle East. While the work I did there was important, I would never compare it to the danger and sacrifice of the guys on the ground in Iraq. But I felt the weight of my role as I answered questions from the guys driving the streets of Baghdad on their ability to engage, knowing that my advice was to protect them both physically and legally.

We were living in airconditioned tents at the time and one day there was a fire caused by the electrical system. The entire 20 man tent went up in flames in 18 secs. Luckily no one was asleep in there at the time. We immediately inspected all our tents, which were not Australian owned, and discovered that they were a death trap. Only one exit point, electricals configured with multiple converters on top of each other. The CO immediately moved us all. There was hard accommodation under construction, and it wasn’t quite ready, but none of us signed up to die in fire.

Baghdad International Airport 2004. The facility was run by Australian Air Traffic Controllers.

Back in Australia for 6 months, in April 2005 a Navy Sea King helicopter crashed on the tiny island of Nias in Indonesia, while providing humanitarian assistance after the Christmas 2004 tsunami and aftershocks.

Nine Australian service personnel were killed and two badly injured. As there were Air Force victims, I was appointed to the otherwise Navy legal team to inquire into the accident. It remains to this day what I feel was one of the most important jobs I have done in the Air Force. I travelled to Indonesia to interview the eyewitnesses, who had never seen a helicopter before this one; to Nowra to speak with maintainers, to Canberra to speak with the crash investigators, and finally the Board of Inquiry in Sydney. There is an intense sadness associated with this kind of work, combined with a deep need to find the truth and prevent another accident. Military facilities until very recently have had a lack of female toilets, and I would often find myself at the bathroom sink next to a family member of a victim. All I wanted was to take their pain away; all I could do was give them facts - none of which would achieve that.

These are the heroes of the Nias accident – local Indonesians who, despite never having seen a helicopter before one crashed in front of them, made every effort to pull people out. April 2005.

In 2005 I spent ANZAC Day on the island of Nias, at the Sea King Crash site. This memorial recognises the sacrifice of the nine Australians who died here 23 days earlier, while providing humanitarian assistance to our Indonesian neighbours,

Helicopter flight - 2005

Being awarded Commandants Prize.

This was awarded for my all-round performance on my Officers Training Course, Pt Cook, 1999. Presented by Commandant, RAAF College, GPCAPT Kelly.

I didn’t stay until the end of the BOI. After six months my boss wanted me back in Amberley and my two children – then 4 and 2, needed their mum. And I needed them.

So I went home.

To be continued next edition……..

|

||

|

|

||

|

Paddy asks, “Mick, how did you get on at the faith healer meeting last night. Mick replies, “He was absolute shite. Even the fella in the wheelchair got up and walked out !”

|

||

|

35 Squadron was formed at RAAF Base Pearce in Western Australia in February 1942 under the command of Flight Lieutenant Percival Burdeu and was initially equipped with a Fox Moth and a de Havilland Dragon aircraft. The Squadron commenced operations in March 1942 transporting cargo and passengers to Geraldton, Rottnest Island and Kalgoorlie. It relocated to Maylands Airfield in Perth on 6 April 1942. (Maylands was Perth’s first airport but was closed in 1963.)

The de Havilland Dragon made a forced landing into the sea south of Dongara (350 miles NW of Perth) reducing the squadron down to its lonely Fox Moth. A Moth Minor, a twin seat trainer, was acquired shortly later, though was not that suitable for transport operations.

Two Fairey Battles joined the squadron in September 1942, again not that suitable for transport operations. A second Moth Minor and an Avro Anson joined the squadron in October 1942 followed by a Dragon Rapide (right) in November 1942. Six Tiger Moths and a Northrup Delta joined during December 1942 through to January 1943.

35 Squadron relocated back to Pearce on 5 August 1943 and eventually replaced their strange collection of aircraft with Dakotas on 18 December 1943. The strange collection of aircraft was then inherited by 7 Communications Unit RAAF. The Dakotas based in Pearce commenced freight and passenger operations to as far as Broome in Western Australia, and Essendon in Melbourne. The Squadron moved to Guildford (now Perth’s main airport) in Western Australia on 11 August 1944. A Detachment of 35 Squadron was established in Brisbane in August 1944 for special duties in eastern and northern Australia.

Three Dakotas from 35 Squadron flew to Higgins Airfield on Cape York (right) on 17 October 1944 to fly a special ferry service to Aitape on the north coast of New Guinea. A Detachment of the Squadron began operation from Townsville and staged through Iron Range, Merauke, Hollandia, Tadji and Noemfoor. Another Detachment was based in Darwin in the Northern Territory.

On 31 January 1945 an advance party left Guildford for Townsville, arriving there on 3 February 1945. The rest of the Squadron arrived in Townsville in February and March 1945.

35Sqn Officers’ Mess, Townsville. 1944

They started scheduled operations to bases in eastern Australia and New Guinea on 1 April 1945. A Detachment was based at Morotai in late April 1945.

The Detachment at Morotai closed in April 1946 and scheduled services from Townsville ceased in March 1946. 35 Squadron was disbanded at Townsville in June 1946.

|

||

|

|

||

|

My wife has these days when she wants "us to talk about things". We were discussing aspects of our future so when it was my turn I asked her "What will you do if I die before you do?” After some thought, she said that she'd probably look for a house-sharing situation with three other single or widowed women who might be a little younger than herself, since she is so active for her age. Then she asked me, "What will you do if I die first?” I replied, "Probably the same thing."

|

||

|

35 Squadron is a completely different affair to what it was all those years ago. Today it is a very technological organisation, flying state of the art aircraft, using state of the art maintenance equipment and housed in state of the art buildings at Amberley.

Today it operates 10 of the Spartan C-27J aircraft. The Spartan is not a straight replacement for the RAAF's much-loved Caribou, but nor is it a mini Hercules even though it looks a bit like one.

While it shares some systems with the Herc, it's definitely a different beast. Because it's from a smaller production line, it's a handmade sort of aircraft. Its publications have a very different philosophy, which has been interesting for the Sqn’s maintenance team to learn and to think about things in a different way than perhaps with Lockheed Martin maintenance publications.

It is now three years since the first of 10 Leonardo/L3 C-27J Spartans entered service with the RAAF's 35 Squadron at Richmond.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Since then, the unit has been building its fleet and personnel and has conducted operations in Papua New Guinea and has taken part in major exercises in New Caledonia, Guam, New Zealand and in Australia.

An initial operational capability (IOC) for the aircraft was achieved in December 2016 and final operational capability (FOC) is expected to be achieved in late 2019 and it has filled all its personnel slots.

The man tasked with bringing the C-27J to FOC is 35SQN Commanding Officer Wing Commander Ben Poxon, who came to the aircraft with more than 3,000 hours on the C-130J Hercules. A veteran of seven tours of the Middle East on the C-130J, he completed a philosophy master's degree at the US Air Force's School of Advanced Aerospace Studies in 2014.

Ben said "From there, I wanted to command 35SQN. I saw the C-27J capability pretty much at the same stages where I found the C-130J capability in 2005. It is an immature capability with plenty of room to grow and now I've been flying it for 12 months, I'm glad that I did."

"35SQN's mission is to prepare the C-27J for operations. The first step along the way that we've accomplished was when we reached IOC in 2016. This needed us to have a capability to move passengers and cargo to conduct air-land or airdrop. It mainly focused on the humanitarian assistance disaster relief (HADR) or aeromedical evacuation (AME) missions."

Ben describes the path to FOC as a 3 layer crawl-walk-run approach to capability generation, and defined the squadron's current status as being in the walk stage about to break into a run.

"From an air-land point of view, the lower layer is airlift support which is moving people and cargo in a peacetime role such as HADR, the middle layer is airborne operations that introduces operations in a threat environment, and the top layer is special operations or specialised role environment. "The middle layer, what we're really focusing on now is the airborne operations environment where we have a threat," he added. "We'll build on the crews' experience in airlift support, and then introduce more complex environments where we have to think about a threat akin to the Middle East."

In such an environment, 35SQN crews would be wearing body armour and carrying weapons, and would have the aircraft's self-defence systems enabled so they can conduct airdrop or air-land operations anywhere in the world. To this end, the squadron will participate in two major exercises this year, Hamel and Pitch Black, where it will develop and practice the skill-sets required to operate in a tactical threat environment.

For Exercise Hamel the Sqn’s objectives will be to provide a reliable and repeatable resupply of ammunition, food, and medical supplies into the field. The C-27 is the truck in the sky. It provides options to land manoeuvreable forces on the battlefield. This will allow commanders to consider the C-27 to insert or extract personnel and cargo rather than typical land manoeuvre.

"At Pitch Black the Sqn will assess its ability to integrate into a fifth-generation air force, whilst supporting the special operations community. They will train in areas such as precision airdrop using GPS-guided chutes and dropping from quite high altitudes. The special operations support mission will be a key focus in 2019 in the lead-up to FOC and will continue to be developed throughout the aircraft's life of type.

|

||

|

I hate it when a couple argue in public and I miss the beginning and don’t know whose side I’m on.

|

||

|

FOC will get the Sqn into a semi-permissive environment, akin to what exists in Iraq or Afghanistan. But with various avionics upgrades coming in the next two years, it would certainly be able to move into a higher threat environment in the coming years.

Ben says "The type of aircraft and the capability each Air Mobility Group (AMG) aircraft brings adds a different slice to each capability set. If we talk about C-27, specifically 'how' we will employ it is where it's best capability is. If we employ it the same way as a C-130 or a C-17, we'd be doing it a disservice. This aircraft is more for intra-lift on the battlefield and our focus is in air-land integration closely aligned to the employment of the Chinook in a capability sense."

C-130 or C-17 missions will typically sit on an air tasking order (ATO) generated by an air operations centre (AOC) that runs on a 72-hour cycle. This represents centralised command and decentralised execution but because the battlefield is a dynamic environment, the C-27 will operate in direct support of Army units alongside helicopters from a forward location so they can be quickly re-tasked if necessary. The C-271 has the ability to operate on a reduced battle rhythm of less than 24-hours so crews will plan with the people that actually conduct the tasking. This will provide more responsive, reactive tasking.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Where the C-27 would take the mission instead of a Chinook, depends on the range from the base and what's at the other end. The C-27 can go at least three to four times further, faster, and can carry more, but obviously it needs a landing strip or something to land on. It provides a unique niche of capability between the C-130 and Chinook in this sense.

With the C-27 sitting between the CH-47 and the C-130, the wider ADF is also conscious of the need to support this hub-and-spoke concept and has planned the building of cargo pallets so they can be offloaded from a larger aircraft to a smaller one without having to be broken down and re-built. While this may sometimes see the larger aircraft under-filled, the time-saving advantages in getting equipment to the forward bases and onwards into the field cannot be understated.

Part of integrating the C-27J into service has been the process of educating the aircraft's customer base. One problem they have is that the C-27 was sold as a Caribou replacement and to a certain extent that's correct. It is a twin-engined, smaller, light tactical transporter but the battlefield of today has changed.

The C-27J is almost twice as heavy as the Caribou. What it does gain in the extra weight is range, it gets speed, it gets flexibility, but it also has defensive systems and comms that allow it to integrate on the modem battlefield.

While the C-27J doesn't have that much of a shorter landing roll or takeoff run than a C-130J, where it excels is in its ability to land on strips with a much lower pavement classification number (PCN), a rating used to indicate the strength of a runway, taxiway or ramp.

As a consequence, while the C-27 carries a lot less than the Hercules, the RAAF claims it can access up to 1,900 airfields in Australia compared to about 500 for the C-130J. That's why when you look at this capability, special operations are very excited about it. Overall, AMG has increased the access to airlift with 35Sqn’s 10 aircraft, but also, the C-27 is an aircraft that can go a long way with small teams and their gear.

|

||

|

When I say “The other day” I could be referring to any time between yesterday and 15 years ago.

|

||

|

The RAAF C-27s are to receive a mode 5 IFF upgrade and Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast (ADS-B) from later this year which will allow them to operate without restriction in international airspace. The first upgraded RAAF aircraft is currently in Italy being modified, and the rest of the fleet will be modified in Australia by RAAF and Leonardo technicians. ADS-B is the new transponder format being used by civilian and military air traffic control services. Similarly, Mode 5 IFF is the latest version of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s friend-or-foe identification system.

The C-27J airframe also features numerous currently blank antennae and apertures in anticipation of these being used for possible future communications and sensor additions.

The C-27’s commonality with the larger C-130J was already paying dividends for the RAAF. One of the best decisions that was made was to have an aircraft with a similar engine. It's been a proven engine over many years and everything from the logistics to the contracts, to even the guys working on it has been a very simple transition. Another key advantage is the ability for 35SQN to borrow maintenance people from 37Sqn to assist in supporting and training the C-27 maintenance workforce. Similarly, due to the similar cockpit layouts and mission planning systems, the training for a pilot transferring from the Herc to the Spartan can focus more on the aircraft's different handling characteristics and capabilities, rather than having to start from scratch.

The avionics architecture is very similar as well. The Communications, Navigation and Identification system (CNI) or the Flying Management System (FMS) is almost identical to a C-130J, so the Squadron can bring a pilot from 37Sqn over to convert on the C-27J in six weeks, whereas it probably takes a good five months to train someone from the start or from another aircraft type. The roles are also very similar. Everything from intelligence products, to briefings, to how 35Sqn conducts business for loadmasters down the back is almost identical. It's a very good purchase from that point of view.

With his C-130J background, Ben Poxon said he felt at home straightaway in the cockpit of the C- 27J. "Most of the systems avionics architecture, head-up displays, head-down displays, are all taken from the C-130J. I passed a simple day-night check on the second simulator ride. In addition, I passed an instrument rating test after about seven sims.” Being a smaller and lighter aircraft, the C-27J handles quite differently to the C-130J. In the tactical environment, pilots can stay lower for longer as the nimbler C-27J will get them into and out of valleys and over ridgelines much quicker, but the C-27J is more difficult to land as it sits on a narrower main undercarriage track and can dip on the nose and gets light on the mains when braking.

|

||

|

Never ask a woman who is eating ice cream straight from the container how she’s doing!

|

||

|

|

||

|

It is challenging on the runway and in higher crosswinds, but it's just something that you have to get used to. Unlike the C-130J which is very solid during the landing ground roll, you've got to continue to fly this aircraft until you have stopped.

The C-27J also has a higher thrust to weight rating, so it climbs very quickly. It's got a lot of power behind it. Where a pilot would typically put a C-130's nose up to 10 degrees for take-off, you can put the C-27’s nose up around 17 or 18 degrees for take-off. Even with a load, it's still a bit of a rocket, but on one engine it's challenging like any twin-engine aircraft on one would be. Whereas if you lose on engine on a C-130J you barely notice it. But in this aircraft, losing one engine is almost like losing two engines in a C-130 at the same time - it feels very slow to climb and it requires quite adept handling skills.

|

||

|

|

||

|

While most of 35SQN's pilots had come from other multi-engined types, the Squadron is now getting more straight from 2FTS. Up to now, as well as from 38Sqn’s King Air, some have come from 37Sqn’s C-130J and a few from the 10 Sqn’s P-3 transition, but now they are starting to get 2FTS graduates. They need the 2FTS graduates to come through and do a typical co-pilot to captaincy tour. Until now 35Sqn has focused quite heavily on the flying supervision side, but if you have too much experience, then you have a top-heavy squadron and risk progressing at a rate unachievable for 2FTS students.

At the moment 35Sqn is short on pilots This is not due to the availability of pilots, but more to do with getting the pilots through the training system to the C-27. Pilots new to the C-27 who have come from a type other than a C-130 do a six-month initial qualification course at the end of which they are able to conduct airborne operations missions competently.

|

||

|

Why is it if you lose a sock in the washing machine, it comes back as a Tupperware lid that doesn’t fit any of your containers.

|

||

|

At least six weeks of that course is currently conducted at Pisa in Italy, but this will transition to Australia from 2024 when a C-27J simulator is installed and certified at Amberley.

|

||

|

One 'bograt' pilot new to the C-27 was Pilot Officer Katherine Mitchell who has come straight to the aircraft in 2018 after being awarded her wings at 2FTS. After finishing the ground school phase, she went over to Italy for five weeks for the simulator phase where she completed her basic instrument flying tests after which she returned to Australia and started her first flying phase on an around Australia 'Aus-trainer’.

From there she will progress initially as a trainee co-pilot under the guidance of an experienced pilot, before being rated as a C-Cat co-pilot. From there she should be able to achieve her captaincy on the aircraft later this year.

As with all RAAF flying operations, C-27 pilots are given category ratings based on their proficiency. "D-Cat is safe operation of the aircraft, and a C-Cat is proficient, so you can employ that aircraft proficiently in a mission. A B-Cat pilot is highly proficient so therefore your chances of mission success are increased, and that also aligns with a captaincy. Then A-Cat is 'select'.

No less important than the pilots are the C-27J's loadmasters and like the pilots, the 'loadies' have a mix of experience and backgrounds. 35Sqn has received their first direct entry off-the-street loadmaster. Whereas, traditionally it was a re-muster role, Air Force has identified that it needs to reach out further without taking a lot of the resources and corporate experience, and actually develop more.

|

||

|

|

||

|

35Sqn has eight “off the street” loadies in training, one of which is an Army private who made the lateral transfer across and who, when he graduates, will be a corporal loadmaster. 35Sqn dropped the rank from sergeants down to corporals so they can tum that top-heavy, warrant officer-centric workforce into one that is more merit-based.

Ben Poxon thinks the best thing about this aircraft is the Sqn can adapt and use innovation on the aircraft cable and cargo handling systems. They switched to the Brooks & Perkins cargo handling system on the Heres, but through the nature of the missions and the complexity and the weight saving they wanted to achieve, 35Sqn ended up removing it. On the C-27 they can install it as required per mission. That gives an extra half a ton of cargo or fuel or whatever else.

The Squadron’s Senior Engineering Officer is SqnLdr Amanda Gosling who came from 37Sqn. She says: “35SQN conducts all of the maintenance on the aircraft. The men and women who work on the aircraft are learning all the baseline skills that you would need to repair a battlefield airlifter in the field. 35SQN looks after the C-27J with the support of Northrop Grumman, which last November was announced as having been awarded a performance-based contract to maintain the aircraft, but unlike most industry-led sustainment contracts, Northrop Grumman doesn't actually lay a finger on the aircraft itself. They provide the engineering services. They're the platform steward for the aircraft, so they look after our documentation suites, configuration control, structural integrity and the logistics pipeline."

There is also a small team of Leonardo field service representatives who work through the Northrop Grumman contract, while engine maintenance is performed by Standard Aero, which also looks after the C-130J's engines.

It's been quite a journey for the maintenance team which has been with the Sqn since it got the first aircraft, right up until now. They were here for the first wheel change, the first time we did everything. The first time we opened those publications to go through a procedure.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The squadron is also being more efficient with its workforce, by crosstraining maintenance personnel across multiple trades. There have been a lot of things that they don't do on other air force platforms, because 35 Sqn does the deeper maintenance level servicings as well as the operational servicings. The squadron has been established with a 'grey trader' initiative in mind, so for any task that they can cross-trade or cross-train people. They’ve got 'black handers' pulling out avionics boxes and avionics guys helping on brake changes. As you go up in complexity of the task, they just make sure that there's a core trained person as the maintenance manager.

The C-27J has a phased maintenance approach, where every part of the aircraft is serviced over a fouryear cycle. It's also based on hours and landings but that does allow the Sqn to increase the amount of time they’ve got the aircraft online. As a consequence, the longest a C-27 will be out of service is about eight weeks, whereas a C-130 can be down for six or more months during a major service.

One of 35Sqn's strengths in introducing the C-27J is the diversity of experience of its personnel. They’ve got such a diversity of backgrounds through the organisation and there's been some really innovative ideas coming from those people.

|

||

|

I finally got 8 hours sleep. It took me three days – but whatever. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|