|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

John Laming Aircraft and other stuff. |

||

|

Random memories of a Navigator. Caught up in World War II

Mike Bayon

We lived at King’s Farm, Little Shelford, four miles away was the RAF station at Duxford. My sisters were 19 and 17 and Canadian cousin Peggy, aged 18, was over on a long visit. Not surprisingly, the place soon became known as RAF King’s Farm. My mother was extremely involved in her daughters’ affairs of the heart. “Isn’t your niece, Peggy, pretty?” asked one innocent young pilot. “Oh yes charming” enthused my mother. “Isn’t it a pity she’s got worms?”

|

||

|

|

||

|

However, eventually my sisters married pilots and war was declared. Both my sisters became pregnant, Peggy went back to Canada and the phoney war creaked along. Then came Dunkirk and for a spell seven or eight exhausted soldiers were billeted with us; and James and Bill were flying for hours every day. I well remember both of them at dinner (we still had a white damask tablecloth and a huge silver soup tureen and a three course evening meal), falling asleep on the table between courses. Then suddenly the Battle of Britain was upon us.

It was a little before 8 o’clock on a clear, dewy Sunday morning. Eighty German

planes came winging over in tight formation, pretty high. Three Spitfires beamed

in to attack. I could hear the gunfire and see the absurdly pretty cotton wool

burst of the cannon shells. One of the Spitfires was hit (I was not to know it

was James, Zoë my niece’s father). He was pressing home an attack on a Dornier

when a Messerschmitt from behind completely removed his foot with a cannon

shell. Glycol from burst hydraulics was burning his face and hands and soon he

realised the plane was out of control.

He fell a few thousand feet and then realised that he was in danger of losing consciousness, so he pulled the ripcord. As the chute appeared and he began to swing down, he took off his flying helmet and with the intercom cords, he tied a tourniquet just above his knee. This undoubtedly saved his life. He landed in a field near Whittlesford and a seventeen-year-old farm hand ran up with a pitchfork, thinking he was taking a German prisoner. Some years later, by sheer chance, James found himself teaching this man to fly.

I finished feeding the chickens and came in from the field. Cynthia, seven months pregnant, was standing very straight and very tense in the hall, listening to the RAF doctor. He had decided to “break it gently”. He took an eternity, constantly urging her to be brave; and so, of course, she thought James was dead. He would have done better to say “your husband is alive and in no danger of dying; but he has been wounded” and take it from there. As the doctor finished talking, the baker’s wife ran in from next door to tell our cook the news in detail. We were never able to unravel how the village grapevine had been so quick and so accurate. James was given a tin leg, went on to become Churchill’s private plane spotter and then became a flying instructor. Bill was awarded the DFC for shooting down a number of German planes.

Of course, I would be a fighter pilot. Nothing else occurred to me as even a possibility and so I went to flying school. I took longer than the average to fly solo and on my first solo landing bounced so high, my instructor suggested that I should have switched on my oxygen again. At the end of the course I failed ignominiously. I was summoned to the selection committee “you will be a navigator” said the voice of authority. “I can’t” I replied. “Why not?”. “I can’t do maths” I explained. “You have a trained mind. You can do maths” intoned authority. “I just happen not to be able to do maths” I said. The reply was uncompromising. “You can do maths; that is an order”.

So, more tests. I couldn’t really see the letters with one eye; luckily they tested my good eye first and I memorised the letters. We stayed in huge blocks of flats in St. John’s Wood and heard the lions roaring at the night in the zoo. We went first to the Grand Hotel, then to the Hotel Metropole at Brighton. There a Messerschmitt came in low over the sea, machine guns blazing. We all dived for the floor. There was one casualty – a bloke was scalded as the tea urn was riddled with bullets.

We were in units of 44 blokes. One day, as we numbered off, it turned out that one guy, unfortunately named Belchamber, had got into the wrong unit; so there were 43 of us. “’ave we give berf?” asked the corporal witheringly. When we found Belchamber was to blame, his wrath knew no bounds. “Right there, dingdong pisspot” he bellowed. “Get fell out as you was”.

We were sent up to Manchester. I was put to swilling out the cookhouse with a slightly effete musical scholar from King’s College, Cambridge, John Sidgwick. Very politely he said to a brawny young WAAF from Birmingham “excuse me, have you a hose?” “Oo the fuckin’ ‘ell do yer fink I am? She demanded truculently “Errol fuckin’ Flynn?” “Oh dear” said John “What an exceedingly coarse young woman”.

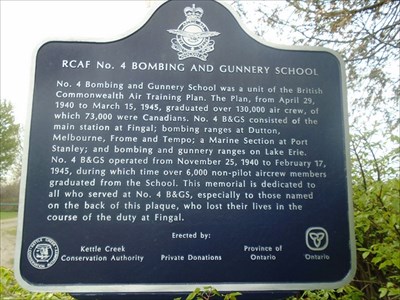

From there we went to Canada and I began to learn to navigate. If your pilot asked where you were, you put your thumb firmly down on the map, covering perhaps 100 square miles and said confidently “just there”. Then he felt secure and you could sweat it out in peace. I flew across Montreal and was told to photograph a bridge over the St. Lawrence but I pressed the wrong tit and dropped a bomb on it instead. I must have missed - I heard no more of it.

I went to bombing school; in Ontario and discovered that I was rather good at it. Quite a surprise. I went to Washington DC on a weekend’s leave and emboldened by half a dozen Old Fashioneds, I chased a delectable girl round and round the Lincoln Memorial till I caught her and made a heavy date for the next night. I turned up, stone cold sober, in best blue and shaved to the bone – and focused on her. In the cold light of day she looked subtly different. Buck teeth, pebble lenses a body like an unmade bed, an advanced case of galloping acne; and I’ve seen better hair on a rat’s back. This time she chased me round the Lincoln Memorial.

Back to camp. A twenty week course, 24 of us on it – well 25 but one was called Brian Murphy. Apart from the smelliest feet I have ever encountered, he was also as dim as can be and he not only slept through the lectures but did so stertorously. Yes, there were 24 of us on the course. I was petrified that I would pass out bottom of the course, so I never once went out of camp during those 20 weeks nor did I fail to work every evening. Eventually, I got my plane spotting, on unfamiliar photos, to the pitch that I got 100 planes right out of 100, an exposure of 1/100 of a second. When I think that now I don’t know the difference between Ernie and the Cabstar, I admit, I am impressed.

I could read all the stars in the heavens, I could do Morse code and I even took

longer steps to save leather “for the war effort” – I was a very earnest young

man. The others looked on me with a kind of bemused affection. They decided that

if we passed our navigation schooling, they would all stand me a drink. We did

pass, and I passed out top. So off we tootled to the Yacht Club, very smart. I

was shouted 23 drinks. I remember there were 4 or 5

I began to feel unusually intelligent. I got to the top of the 20 step flight of stairs to the road, tripped on the top one and went A overt T straight down into the road. I sat down solemnly on a heap of snow. “You’re smashed” they said. “Nonsense” I replied, “I am in full command of my faculties and I’ll prove it. There is Orion, there is the North Star, there is Aldebaran, and Betelgeuse has just ducked behind a cloud”. Horribly, later that night I was sick and next day I felt like death. I was a nasty bilious colour, and it was our passing out parade.

We all bulled ourselves up and lined up on parade. I could feel myself swaying. We had to march up to the Air Commodore, crash to attention and tear off a smart salute. He would then pin on our brevet; another salute, about turn and march back. I tottered up to the gold braided emissary of God Himself and crashed to attention. It was fatal. I closed my eyes and stood there swaying. Three times he aimed the brevet and missed. Then he committed and drove the pin firmly straight through my left nipple. “Ow” I said sharply. The whole parade was now suppressing laughter. I knew I had to retrieve the situation. “Sorry Sir” I mumbled “I meant ‘Ow Sir’”.

The rest of the course was sent to heavy bombers, to Coastal Command, to reconnaissance planes. I alone was sent to Mosquitoes, Pathfinders. The elite of bombing command. We were to be a brand new squadron, 3 Brits, one Canuck, the rest Aussies. For some reason, I was the only member of the flying crew on the whole unit who was not an officer. So, on the first evening, over drinks in the Mess, all the blokes teamed up. Next day we turned up for briefing and I was the only one without a pilot. I looked at the various pilots and thought “that’s the one I’d like as my pilot”. A tall raw bred blond Aussie called Douglas Hereward Swain from Toorak in Victoria. We all went along to the decompression chamber to test our ability to withstand low pressure. One navigator dipped out, Doug Swain’s. He got agonising bends, so in actual fact did I – but I decided not to say so. So Doug and I were now a partnership.

Doug said “Right now my ambition is quite simple. I want us to be the best bloody aircrew in the RAF and that means in the world. As for you, you can make any bloody mistake you like (“that’s good of him” I thought contentedly) – “ONCE” he added menacingly. We went on our first flight together and Doug decided to feather one engine. What he did not know was that you could not restart an engine in mid-air, so our first ever landing together was a single engine landing.

We were briefed and ready to take off for our first bombing trip. Cologne. Quite a short trip. As we got over the target, I was amazed how vivid the scene was. Lots of searchlights raking the sky and occasionally a plane would get caught in a cone of searchlights and glow like a moth. Vivid cascades of target indicators in fluorescent red, yellow or green and decoy German indicators subtly different in colour. Bomb bursts, flaming buildings, tracer bullets, flak bursts. It was all very stimulating.

I crawled down into the nose pf the plane, to lie on my belly and guide Doug in on the target. I got a kink in the oxygen pipe so I became a bit drunk from Anoxia. “Port, port, port” I said. I felt the plane slew slightly. “Port, port, port. Now starboard”. I gave a little giggle. “Now back a bit”. Doug didn’t panic. He realised what was happening and began to drag me out by my legs. I protested. “It’s pretty out there” I said. He hauled me back, took off my oxygen mask and put his mask over my face. I recovered. Doug was now slumped over the steering column and we were plummeting down. I took off his mask and put it back on his face. Well, if you survive the idiocies of your first ten or twelve operations, you may well survive them all.

About now, I decided that if radar was the key to success, I would master it. We used to have two nights of operations and then one night off. On my nights off, I would go along to the radar unit where a thin dark radar aircraftsman and his plump jolly girlfriend would teach me all they knew. I became an expert, accurate at finding my position anywhere on the airfield to within six feet, sight unseen. This was to save our lives later on. At this time, a pretty little blond WAAF called Rose (I never took her out and I don’t think I ever learnt her surname) began to feel she was my lucky mascot. If she kissed me goodbye on every trip, I’d never be killed. So, even if take-off was at 3 a.m., she would be there to kiss me. She’d come back from leave to see me off. She never once missed out. I wonder what happened to her. She had a malformed nail on a finger of her left hand.

Now I’d like to find my logbook but I can’t. Perhaps it’s just as well. Only the most important things will stick in my memory.

I suppose I might just describe a typical day if you are flying at night. In the morning you would contact your ground crew and when they gave the plane the OK, it was ready for a test flight. We had a magnificent ground crew, they really were our friends and would work any hours to get things right for us. We’d fly for perhaps half an hour testing and testing. Or we might fly for maybe two hours, including a trip to the practice bombing range on the Wash. You would sort out your hours to fit in your meals. It might be a 5 p.m. take-off or at any time up to 3 a.m. Whatever the time, the kitchen staff would be on duty and if you didn’t feel like a proper meal, there was a huge cauldron of soup always simmering on the stove, a kind of huntsman’s stew.

Aircrew were allowed fresh oranges with any meal, while the Weathermen, Air Controllers and so on, looked on slavering. I simply knew I must not give the precious things away, so I hardly ever ate mine; some of the aircrew delighted to gloat!

Perhaps an hour or two before take-off you’d go along to the Briefing Room, sitting in pairs, each with his crew member. You’d learn the target, the route and back (Doug and I always came back in a straight line – never mind the subtle route worked out by control), the weather and above all, the winds expected, what load you’d carry and what trouble spots you might expect. A great deal to work out. The pilot was the captain of the plane but in fact his job was often surprisingly boring, not quite that I suppose; perhaps the word is “undemanding”. He would have three moments of high drama; take-off, with full bomb and petrol load; over the target; and landing when you were tired and although you might have heard the shrapnel hitting the plane, you had no real idea what damage had been done, what state the hydraulics might be in, whether the flaps would respond and so on. Of course, the target area was the high spot of the performance for both of you. But for the navigator, take-off and landing were comparatively relaxed. There wasn’t a thing you could do. All you had to do was to be supportive, by showing your complete faith in your pilot and in Doug I had an outstanding flier. He had all the qualities.

Obviously, there were mini-crises crossing the coast of Europe, or if you went

too close, to the islands of Heligoland, or if a night fighter picked you up.

You had a device (called rather endearingly, ‘Boozer’) which told you by a dull

red light when you were being tracked by German Wurzburg gun-laying

Right, so Boozer glowed dull red. Then it would shine bright red. This meant they were training their guns on you. On you, not on the next plane. Here the navigator, however busy he was (and often you would work at an intensity to make you sweat) had to take over. If you merely swerved about like a headless chicken, the Germans marked down your track as perhaps half a mile wide and automatically cut down on your airspeed. Then up would come the box barrage and, I suppose, down you’d go. Though I did not mind the thought of death, I did hope I would not be burned to death.

No, what you had to do was turn a full 600 to port (the light would fade as they lost you); then as it glowed bright red again, give it 20 seconds for them to lay the guns and the flak to travel up, after all we were 5 miles up, and then turn 600 to starboard. It used to make Doug and me laugh delightedly to see the box barrage wasted where they hoped we’d be. Of course, over the target, the Boozer would be bright red almost continuously.

However, there was another little light on the Boozer which did not come on often. This was a little white light that meant an enemy night fighter was on your tail, tracking you with radar. If you had a cat’s eye fighter, the first warning you’d get would be the tracers going past; but both of you had a seat back of heavy armour plate. If the white light went on, it was like being on a bucking bronco, or in a dinghy on a rough sea. Your pilot would go mad and chuck the plane all over the sky. It was all rather exhilarating.

The Aussie pilot with the Canuck navigator seemed to be particularly unlucky. Nearly every night he’d have a German on his tail. One night I prised the secret out of Canadian Mac (his pilot was also a Mac – they were known as Mac ‘n Mac). He used to divert his pilot’s attention and then surreptitiously lift the red cover off the left hand Boozer so that the light shone white. He said it was a ploy to stop his pilot from becoming bored and sleepy. Both the Macs were great bean eaters and as you climbed to altitude the pressure dropped in the plane. The result was inevitable. You used to sit on your parachute as a cushion – the parachute packers used to draw lots to escape from servicing Mac parachutes!

I digress; the operational flight. You go along to Briefing. In those days, I used to wear pyjamas and although of course you were meant to wear full uniform to fly as if you were captured you might be treated as a guerrilla and shot out of hand – I always wore my pyjamas under my uniform. When you got back at 5 o’clock in the morning you were tired and cold and the last thing you wanted was to clamber into cold pyjamas.

At Briefing, the pilots were almost spectators (bus drivers we’d call them). Doug was rather an exception. He wanted to know and understand everything that went on. The navigator would have to work fast, working out the flight plan, sorting out the charts, preparing the logs. Each in his individual style. Like preparing for a party, really rather fun. Then into the crew bus and out to the various dispersal points; each crew was dropped at their own plane, greeted by their ground crew (statutory kiss from Rose). We were then called out in order, taxied to the end of the runway, took off, set course followed by two or more solid hours of intensive work by the navigator (with your pilot telling you that your pinpoint of light to work by is a beacon for night fighters; and do you think you’re Piccadilly Circus on Christmas Eve? You dim it down and furtively turn it up again). You take a radar fix, then another exactly 3 minutes later and then another 3 minutes after that. This gives you how far you have travelled over the ground in 6 minutes. Multiply by ten, compare air and ground position and you know what the wind is. Apply this to the predicted wind and you have a vague idea of how things will be. The normal wind at that height would be about 60mph – so if you ignored it, you’d be bombing about 120 miles from where you wanted to be.

When you were inexperienced, you did carry target indicators –but they might be yellow; and the main force was told to bomb as primary targets perhaps the red; as secondary targets the green; and if all else failed the yellows. What made your pilot smile was if you said “the first indicators should go down in about another fifty seconds” and then dead ahead, suddenly the indicators were there. What did not make him smile, was if they appeared behind us. We would then have to do a U turn (slightly like the same manoeuvre on the M1) and fly back through perhaps 600 planes. This sort of thing made pilots inexplicably tetchy – and for years cured me of being early for an appointment!

This is getting technical. Let’s switch to individual flights.

On one flight, as we left target, my nose started to bleed. Nothing I could do with my oxygen mask on, so it contentedly bled on until I had lost between half a pint and a pint of blood; then it stopped of its own accord. When I got out of the plane, the front of my uniform was sodden red with blood. “Mike’s wounded – get the blood wagon” said one of the ground crew. I took off my oxygen mask to say that it was only a nose bleed. The blood had clotted and congealed. “Christ they’ve shot his face off” said the young fitter and fainted. Not a nice cushiony sort of stage faint with the legs buckling – no, he fell straight back like a board and I heard the crack of his skull on the concrete. The blood wagon tore up, he was put on a stretcher and away he went. This was the sort of thing that tended to upset Rose.

Obviously all the worst things occur in your tour of operations. Like young birds, if you can last the first few hazardous weeks, the odds lengthen. Churchill had decided that as a propaganda ploy, Germany should be bombed for 100 nights in a row. If the forecast was appalling – risk of ice at height, which would distort the wing shape so that you fell from the sky; or heavy fog on return; or towering cumulus clouds containing up and down draughts within feet of each other, of more than 100 mph, strong enough to toss a Lancaster round like a leaf – if there was this risk, four engine bombers must not be involved, with their crews of eight men. Send in the Mosquito boys – a plywood body to the plane and a crew of only two. Much more expendable.

We had no defences except our speed and manoeuvrability. Against an enemy fighter, we had to try to elude it. It did make one feel somewhat wimpish! One night of appalling weather, only three planes took off. Two Mosquitoes from another squadron, and Doug and I from Wyton. The idea was for us to do a Cook’s tour - come close to Hamburg, then veer off; the same for Bremen, Kiel, Hanover, Essen etc. etc. So as to alert the air raid wardens, fire-fighters, flak crews, searchlights, night fighters – the lot; and rob them of their sleep, I plotted a bad wind, then lost the radar picture under intense jamming by the Germans and a host of false signals – later I came to recognise the true from the false.

We came up to Hamburg and passed straight over the centre of the city. Every gun in the city opened up. Over 200 searchlights coned on us. The light was incredibly strong and sharp; I have seldom been more embarrassed in my life. It was like walking down Bond Street naked. Doug’s mouth was a grim line as we did our standard evasion tactics. Whatever we did, we must not lose our nerve and lose height – that was how many were killed. Sure, you gained speed – but you became an easier target by widening the angle of effective fire. We moved on to Bremen and all alone we sailed over the centre of the city. We reached Kiel naval guns here, first class gunners. I could hear the flak hitting us. One large piece went straight through our two ton bomb and out the other side. Another cut the steel struts for the bomb doors like scissors cutting a stick of macaroni – sheared through, shiny, clean, not snapped. This bar was thicker than my thumb. Our petrol tanks were pierced again and again, but they were self-sealing so that was all right. Doug always used them first for this reason. We jettisoned them to add an extra 5 knots to our speed.

As we were in the middle of Kiel I found my self thinking “I wonder if I’m frightened? How do I test it?” I held my hand out – it was brilliantly light and I could see that it was rock steady. I put my hand on my heart. It seemed to be beating slowly and strongly. My mouth was not dry, nor were my hands clammy. Then I noticed that I had a thin line of sweat on my upper lip. “ Perhaps this is what fear feels like” I thought. But I was certainly scared of Doug’s reaction and with reason. We landed in stony silence and after the debriefing he said “Go to bed now but I want you to get up early and I want a complete reconstruction of the whole flight, finding out where you went wrong before we flight test tomorrow”. That’s right “You can make any bloody silly mistake you like – once”.

The Mosquito boys had another chore which we did not much enjoy. We would set off on the same route and almost at the same height as the Lancasters and Halifaxes – the heavy boys; then they would swing off one way and we would swing off on our own route. BUT – we had to drop thousands and thousands of strips of tin foil to simulate a heavy stream of aircraft to the German radar. It was fiddly work splitting the packages and pushing them down the chute, cold too; and the slight pressurisation we had in the plane would dissipate. Worst of all, to entice the enemy fighters away from the soft target of the heavies, we had to fire off vivid flares and Verey lights every few hundred yards. It’s not very nice to feel that you don’t count, that you’re expendable!

But now we had done twenty or thirty trips; we were good and we knew we were good. By hours and hours of work in the radar shed, I had become an expert on radar – I, who can’t even mend a fuse; and usually I put in the petrol and leave my companion to see if we need oil! Donald Bennett, the Australian I/C Pathfinders had me to dinner a couple of times with his Swedish wife, to see if I could explain exactly how I knew which were our signals on the radar screen, and which were the German ones. I couldn’t. I couldn’t draw it even, I just knew. I would sometimes be getting accurate radar fixes fifty miles further East than anyone else on the raid. It gave us a great edge and Doug was pleased.

If we were dropping a 4,000lb bomb – which we often were; its terminal velocity in falling was something like 460 feet per second (about 500 klm/hr). In other words, if we had got into a dive, we could easily have passed it. It was a great big clumsy thing, like a cylindrical hot water tank. So, you could release it and all of us had enough pride of performance to do a steady run up to the bombing, however the flak might rattle and the plane would give a great surge as the bomb left it. An anti aircraft shell bursting nearby could feel much like this actually. Then you had nearly a minute before the bomb burst.

Obviously, standard practice was to take evasive action directly the bomb left, with the navigator timing it to photograph the bomb burst. Doug decided he wanted the best photographs in Bomber Command. To this way of thinking, this involved straight and level flight not only for the minute of run up but also for the minute of bomb fall. It was rather exciting to work at this level of perfectionism. We were now briefed to do a low level day light raid on railway tunnels. For days we practised, thrilling. I remember swooping over the brow of a Welsh hill and seeing the sheep scatter, then the raid was postponed and when it did take place, we were on leave. We were deeply disappointed. One pilot came back with blades of barley on his tail wheel. One saw a train accelerating into a tunnel. Just as it shot in like a rabbit into its hole, he dropped his bomb to collapse the entrance to the tunnel. What neither he nor the train driver knew was that the other end had been collapsed ten minutes earlier.

Doug and I had now worked out a way of always being first back. Sure, we did come back in a straight line but so did lots of others. Our secret was to climb to 32,000 feet or higher for the return journey when we weren’t weighed down by bomb or petrol. On the indicator, the reading was very low for airspeed, owing to the thinness of the air; and the climb did take time, but at that height we went like a bullet. In fact, every time I suffered from bends; but it seemed ungenerous to mention it. Doug would stay at height until the last possible moment and then scream down to take first place in the circuit. Obviously, our ears could not cope with this change of pressure. Later, when I shared a room with Doug, whoever woke first would hold his nose and blow and the high pitched squeal as the pressure equalised would wake the other.

Oh yes, I was now an officer. The CO called me in and said I should be

commissioned. I said I saw no necessity for it. I was perfectly satisfied with

the

Then came the first thousand bomber raid; it was like a street party with gatecrashers. Everything that could fly was forced into the air. Ansons from training command, with untrained crews, carrying about a basketful of hand grenades. Shambolic, we felt, but good propaganda. Mike Solomon, from the next squadron, took off with a 4,000lb bomb aboard. One engine cut out at 10,000feet so he jettisoned his bomb, safe, not fused. The bomb did not care; it went off anyway and almost blew him out of the sky. That’s at a range of 2 miles! Next day was very hot. Mick was wearing an overcoat, gloves and a scarf and was still cold. Shock, of course, but we thought it hilarious. He had to go, of course. They should have known earlier when he refused to join 571 squadron because it added up to 13!

We had very little time for indiscipline. I remember flying over Alconbury, an American base. If the Brits got back to base damaged or with wounded aboard, they’d contact control and take their place in the circuit in order of priority. The Yanks were back from a daylight raid. The airways were throbbing with their cries of May Day. Then they abandoned control altogether and came in huggermugger – down wind, cross wind, any old how. No less than five collided at about the junction of the runways and a great pall of smoke rose. It made me very angry.

Doug and I were on a raid on Wurzburg, a small town set among mountains. Curiously my father had been at university there. We had a 4000 lb bomb and were told by Met that it would be a clear night; so the markers were on the ground. We arrived over target and could just see the glow through the heavy cloud. “Let’s go lower” said Doug. Well, once we were on that course, there was no stopping us. We suddenly came into clear air at just under 4000 feet. By now it was really exciting. We were bucketing about, tossed around by the bomb bursts (we’d been told that at less than 5000 feet the explosion would rip our wings off), and we were right into the light flak. We’d never experienced that before. We were both laughing with sheer exhilaration and excitement. With the fires, the bomb bursts and the target indicators, it was vividly, luridly lit up. I’d never bombed visually before. I could see squares and streets and the university – I picked on the railway as my target, two tall towers like King’s Cross. Then we were climbing and wheeling steeply to avoid the pine clad mountains.

We got back last. Rose had given us up as missing. We were last in the queue for debriefing. We were last in the queue for rum, hot water and sugar – better than any sleeping draught if you are cold and keyed up. One after another came to the table. ”What did you bomb?” “Glow in the sky”. Again and again and again. The Intelligence Officer was in the rhythm. Ronald Bennett was leaning negligently against the wall. A lot of the crews had gone to bed. Doug and I were smiling secret smiles even nudging each other like kids. We reached the table. “What did you bomb?” asked the bloke. I looked at Doug; he said “You saw it best. You say”. I said “We bombed the railway station”. The Intelligence Officer had already written “Glow in the sky” and switched off. Suddenly he shouted “WHAT?”. Donald Bennett hurried over; as the news spread, all the other crews on the raid came back – some in pyjamas, some half undressed. Then the various blokes on night duty – cooks, electricians, firemen and so on – all flooded in. Ours was the only eyewitness account of how the raid had gone – where the bombs had dropped, how accurate the target indicators were. Doug was awarded the DFC, an immediate award; mine followed two or three weeks later.

Here an odd story follows. The boffins came up with Oboe, a highly sophisticated form of radar. based on radio transponder technology. The system consisted of a pair of radio transmitters on the ground which sent signals which were received and retransmitted by a transponder in the aircraft. By comparing the time each signal took to reach the aircraft and be returned to the station, the distance between the aircraft and the station could be determined. The Oboe operators then sent radio signals to the aircraft to bring them onto their target and properly time the release of their bombs. But how accurate was it? A subtle plan was concocted which would require no time lapse, no risk to spies or undercover agents. A lull in the bombing was planned and only 3 planes were sent out, each bombing on Oboe. The target was a small German cemetery. The next day the German news was jubilant – “Ze British have Germany last night bombed. But – ha ha ha – zere were no casualties; bodies were attacked – ha ha ha – but zey were all dead bodies. Ze stupid British a cemetery have bombed”.

The British scientists hugged each other – and the production go ahead was authorised.

Radar was our seeing dog – our white stick and so, one day soon after we took off, the radar blew a fuse. I put in another and again it blew. I put in a third – no joy. So I put in a penny – as I’d learnt in the radar shed. I got my three fixes and then the radar caught fire. I beat out the flames with my cap and my bare hands, we got to target and returned; Doug was furious. Then I was mentioned in despatches for outstanding intelligence, initiative and refusal to admit defeat. Even in those days the radar set cost £600 – it seemed to me that the whole world had gone mad. And sometimes perhaps it had. Yet we had our own rules of sanity which are hard to explain now. Our Art Mistress used to say to the first XV “How can you look forward to a match? You know it will be cold, wet, muddy; that you’ll be hacked and trodden on and knocked about”. “True” they said, “That’s the point of it”. They did not know, so could not say, that pride was the motivation and a kind of self-confidence the target.

I used to teach boys Latin. The intellectual loved it – the rugger buggers found it a sore trial. They’d ask me “Why do we do it?”. “Because it’s difficult” I’d say. “That’s no reason” they’d reply scornfully. All right, what’s the point of rugby?” “To score tries”. “How?”. All right, what’s the point of rugby?” “To score tries”. “How?”. “You put the ball down beyond the line – under the posts if possible”. “O.K.” I said, “But why don’t you wait until everyone has gone and then you can put it down as often as you like?”. “Oh Sir – that’s stupid”. Then they’d think and then say ”Wait a minute. No it’s not. I see, it’s the challenge that makes it exciting”.

You’d think that bombing Germany was challenge enough; and so at first it was. But then we wanted to swagger a bit, to take an early bath, to field close to the bat. We knew that if we switched on our radios (which should only be switched on as you baled out to let the rest of the squadron know you were alive, or unwounded as you left the plane) the Germans could home in on us. Yet our squadron had a tuneless little ditty and, as we swung away after the photographic run, one harsh Aussie voice would come over the air and then another and another would join in the refrain. And we’d be laughing with the sheer risk of it.

Odd, unusual – and not very wholesome! One of the heavy boys used to get the whole squadron to use his Elsan (toilet), then he’d make one bombing run – then do a U turn against all the stream of bombers, make another bombing run to drop his Elsan, shouting obscenities in broken German as he did so. Of course, he did survive the war!

The backroom boys put much thought into bombing. How about high explosives first to shatter the roofs and gas mains? This would make the incendiaries infinitely more lethal instead of their bouncing off roofs on to the pavement. How about incendiaries first? Then the ARP and fire-fighters would swarm out to deal with them and be killed by the H.E. How about a mixed grill? In fact, this was the usual pattern. I tried not to think of cities and people and treasured possessions and pets and children. I tried to concentrate on the essential if Germany won the whole world would be enslaved. Then one night the CO said “Berlin tonight. Again. A night on the Spree (Berlin is on the river Spree) and it will create chaos. The city is jam packed with refugees fleeing from the Russians on the Eastern front”. That night I had a nightmare. I dreamt that I saw, in the cold light of dawn, a great heap of bricks and rubble. Drifts of thin smoke wafted around. A woman, swathed in black, was clawing desperately at the rubble. I could see her breath rasping in her chest but everything was completely silent. I could see her nails tearing, her hands bleeding and the desperation in her. Suddenly she saw a child’s thin, bony hand poking out of the rubble. She called out and clawed and scrabbled even more desperately; and as she cleared almost to the elbow, the hand just went limp and I awoke, sweating. I did not sleep for the rest of the night. I just walked around the airfield with my puzzled spaniel, Sheba. There was a full moon; it was very cold and I found a £5 note sodden in a ditch.

From then on, every night and long after the war was over I had that same dream. Yet, I was happy. I was doing something important, something that had to be done and I was doing it well. Another odd thing. We were strongly individualistic, unthinking obedience was anathema to us; yet we were disciplined, deeply disciplined and in spite of our casual dress, behaviour, cars and moustaches, we were surprisingly caring of our ‘best blue’, our new forage caps or gloves; like the Guards’ Officers at waterloo, oddly dandified.

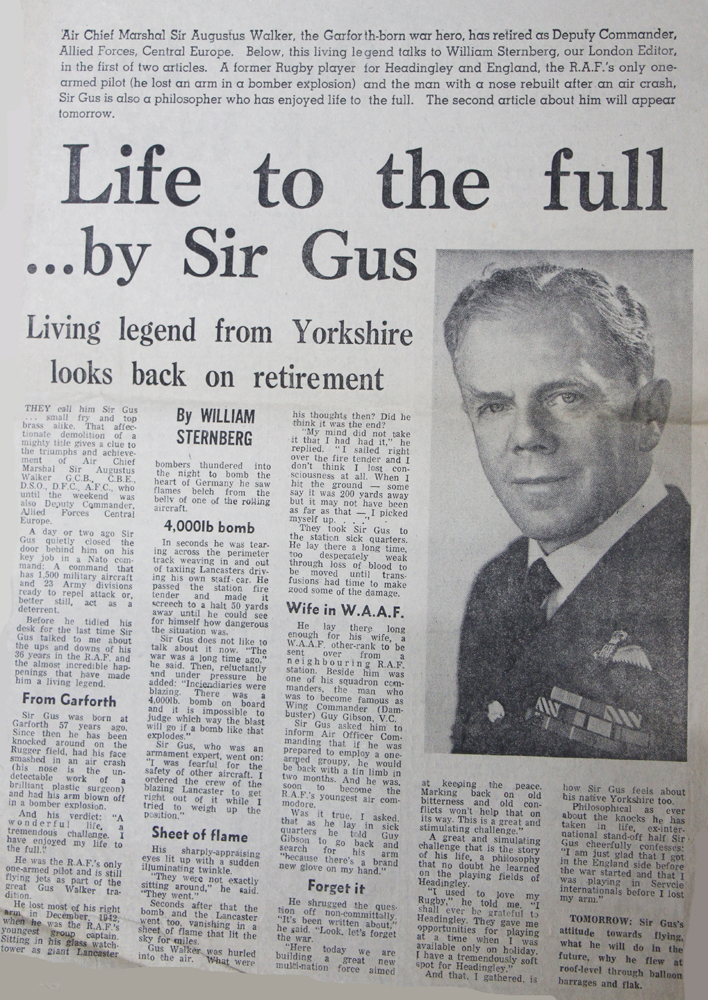

An example. Gus Walker, fly half for the England team just before the war, was CO of a heavy bomber station (Click the pic at right). A Lancaster taxied to the start of the runway and some of the incendiaries broke loose and were rolling in the bomb bay. The crew ground to a halt and set off for the far blue horizon like jack rabbits. Gus, in the control tower, called his driver. “I’m not having a crater blown in my main runway” he said. Two or three hundred yards from the runway he told the driver to stop, and alone he ran towards the plane. He got within five or ten yards of it and the incendiaries, which had burnt straight through the duralumin bomb doors set off the H.E. bombs in one tremendous explosion. Gus, in fact, was saved by being exactly in the skip distance – otherwise the blast would have crushed his lungs. But his right arm was shorn straight off at the elbow. He came walking back to his little vehicle holding the stump of his arm tightly with his left hand.” I may be going to lose consciousness” he said “ I want you to be sure to send a signal to the group that I’ll be back on duty in 6 weeks’ time, still CO of this station. Oh, yes – and could you find that hand of mine? It had a brand new glove on it”.

I had been the officer I/C the funeral of the two Macs. As we always did – as we were taught to do – if a friend were killed, we got very drunk that night. I was travelling back in the crew bus. The Macs had been popular and it was very crowded. On my knee I had a buxom red haired WAAF. Suddenly, revoltingly, she was sick down the front of my best blue. It felt like the last straw.

A few days earlier there was a big party in the Mess. Music, dancing, condoms blown up and stained with the red, blue, green or black marking ink we used for charts. I was no dancer – and I was tired so I went to have a bath. A friend wandered in and very slowly and meditatively poured a bottle of black ink over my head. A minute or two later he came back with an outsize bottle of red ink and began to pour it over my hair. With a roar of rage I leapt out of the bath and pursued him down the corridor. He was dressed, I was naked. As I ran I caught up a fire extinguisher and crashed it against a pillar. Foam shot out and although we were running fast, I kept it steady and was targeting him well. Down the main staircase we belted and suddenly I was in the middle of the main dance floor, and the fire extinguisher was empty. I went back to my bath and locked the door. No mention, no disciplinary action. Odd things were bound to happen.

At Shepherd’s Hotel in Cairo, at 3 o’clock in the morning, we were woken by shouts and screams. A naked ATS girl was making good headway down the hall and corridors, hotly pursued by an equally naked Squadron Leader. He was charged with “Conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman”. He got off because he made the court laugh. His defence was “An officer need not at all times wear full uniform, provided he wears clothes suitable for the sport in which he is engaged”.

At Duxford a young sentry was on duty when a local village maiden tootled past on her bicycle. A/C 2 Dixon whipped out his old man and waved it at her. She complained to her mother, who brought the matter to the C/O’s attention. Poor A/C 2 was now on a fizzer. He prepared his defence meticulously. Brought up before the C/O, he snapped to attention, and in a flat disciplined voice said his piece. “I wish to express my regret at the unfortunate incident that has occurred. Unhappily I was under a misapprehension. I was under the impression that I was acquainted with the young lady in question”. Case dismissed – what other verdict was possible?

Our only daylight raid was rather dull but different – so it sticks in my mind. Our troops had reached the Rhine and were held by stubborn resistance at Wesel. By now we had virtual command of the air. I don’t know how many planes – certainly around 200 bombers – were in the air. We took off, we made our rendezvous, we flew over the North Sea in tight formation while above and below us the fighters weaved and patrolled. We came North of Wesel and swung onto the target run. – no flak – no fighters. A feeling of unreality, like performing in an empty hall. No audience! Contrails were forming and we ran down them as though they were rails. The leader of our formation opened his bomb doors – we did the same. His bomb dropped and we also pressed the tit as his plane surged up under the release of its load. That was it. A non event. But I met an Army officer who was on our bank of the Rhine that day. He said that they themselves were almost in a state of shock, shattered, deafened, addled. Then they crossed the river and because of our mass bombing, the Germans were paralysed – incapable of speech, thought or movement.

London was in the grip of the blitz. If you went up you would sleep in the tube shelters all along the platforms. Not a restful night – babies might cry, trains start at 4.30 a.m., but a great feeling of camaraderie prevailed – no theft, no muggings. From Cambridge nightly you could see the glow in the sky, fifty miles away. One night we set off, twelve planes from our squadron. A disastrous night, Doug and I had quarrelled, so we were split up for the night. I was to fly with Alan Heitman and Doug had Nat, Alan’s navigator; a ratty little Pom. Briefing was over and we were all in the crew bus. Doug came over “I don’t know whose fault the argument was and I don’t care. You’re the best navigator in the world and I don’t trust anyone else. Will you fly with me tonight? I’ve fixed it up with Alan and Nat”. So, I got out at our usual dispersal point.

We took off at about 10 p.m. An early dawn landing. The predicted winds were high that night, 130mph from the West. I plotted my first wind; 130mph from the East. I told Doug. He said “You must have made a mistake”. I took my next wind. Same result. He said “Look, this is absurd. Try again. I’ll concentrate like buggery on my height and airspeed”. Third wind, same result. “We’ve got to believe it” I said. What had happened was that the anti-cyclone had gone through faster than predicted so that we were on the other side of the trough. We were meant to reach Berlin in about 2 hours – it took us 3½. All right, so we’d come back fast, but we’d been bucking a head wind for 3½ hours with full petrol and bomb load. We knew we’d be pinched tight for fuel on return.

We got back to base and the fuel tanks registered empty. Moreover, a warm blanket of air had slid over the cold air, trapping fog, which was forming on the ashes of burning London. Doug contacted base. “Why aren’t the runway lights on?” “They are”. “But we’re right over base at only 10,000 feet”. There’s a bit of fog down here”. The rest of that night is easily told. One plane aborted and came back early with radar trouble, once when we had radar trouble we just carried on. Pretty wet we thought of them. The planes limped in, exhausted, frustrated, short of fuel and no airfield visible. One diverted to Bassingbourn and landed safely. “Taxi in to the perimeter” radioed control. He couldn’t – he had no fuel.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Macs tried to land by radar at Wyton (above). Canuck Mac was not quite accurate enough and they landed on a petrol bowser. Even this great sheet of flame was not visible through the clinging fog. Next day the Medical Officer went to search for their bodies. All he found was one thumb and he callously trod it into the ground with his heel.

John Smith, a good bloke and a bloody fine fly half at rugby, found base but could not land. “Gain height and bale out” ordered control. He tried – and ran out of fuel. His navigator baled out safely. Parachutes were designed to open within 400 – 600 feet. John got out at 180 feet and his parachute was still only half open when he hit the ground. He must have hit at well over 80 mph, but he was fit and relaxed. He rolled with the fall and wasn’t even bruised. When he got back he said “I’m going to look there tomorrow. Just before I jumped, I chucked out my forage cap – it was brand new”. The plane hit the ground at less than 200 yards from where it was found.

Half a dozen others gained height and baled out, leaving crewless planes to crash. Alan Heitman was less lucky. He got back over base, saw no runway, was told to gain height and bale out. Nat opened the escape hatch and froze with fear. A red haired WAAF was talking the planes in. In fact, she was engaged to Alan and they were due to marry on their next leave. She could hear Alan telling Nat to jump, then his urgency as he said “The engine’s overheating. Christ it’s on fire. Jump, jump”. Still Nat clung to the plane. And the flames were beginning to lick at the cockpit. He even struggled with Nat – and still Nat clung neurotically to the plane. Suddenly he jumped and landed safely. But by now it was too late for Alan. The plane was in a spin burning fiercely. The red haired WAAF could hear Alan screaming all the way down, and she even heard the plane hit the ground, though by now she was on her hands and knees under the desk, trying to blot out the sounds. She was on a week’s immediate compassionate leave. By 7 a.m. Nat was off the station, his room empty. He was called up for the Army the next day. The phrase used by the RAF was LMF –lack of moral fibre.

And Doug and I? Well, this was my chance to test the theory of blind landing I had worked out. Run down one radar line until you hit a cross line, do a steady 30º port turn and you’d be lined up with the centre of the runway. Accurate to 6 feet.

We tried it at 300 feet. No joy. We simply could not see the massive sodium lights. We went round again. 200 feet. Not a sausage. “We’ll just have to go lower” I said. “Well, I’ll go in at 30 feet” said Doug. “But you’d better be bloody accurate. The hangars are higher than that”. “Oh that’s OK” I replied. “It will work”. We came in at 30 feet. “Crossing perimeter” I said. Then “Start of runway”. Then “You’d better be quick, we’re halfway down the runway”. Doug gritted his teeth. “I hope you know what you’re doing” he said. “I’ll chuck her down”.

We hit the runway and seconds later we were off the runway on the grass verge. Then we tore through the concertina wire and barbed wire entanglements and perimeter fence as if they were cobwebs. We were still travelling at over 100 mph. Then we hit the hedge and the main road from Cambridge to Huntingdon – and still Doug was fighting to keep her straight. We hit the hedge and ditch the other side of the road and now were in a field of sugar beet, sodden soil. Suddenly the under cart collapsed and we slid along on the belly of the plane. Then we were still and after the intense drama of the last half minute, it was amazingly silent – so silent that you felt you could gather great handfuls of it. I’ve never known a feeling like it. I broke it. “Thank you, Doug” I said “That was good”. Still we sat; we knew we ought to get out in case the plane caught fire; but we felt curiously drained, as though we were waiting for all our innards to catch up with us again.

Again, I was the one to break the silence. “I’ve got some chocolate in my navigation bag. Would you like some?” I said. It was another one of our perks, like oranges, that the aircrews got extra rations of, coarse rather bitter heavy chocolate. “Christ, yes” said Doug – and suddenly we both realised we were ravenously hungry. I broke the huge slab equally in two and both of us just stuffed the whole lot into our mouths barbarously. At that moment the C/O climbed onto the wing of the plane and battered on the Perspex of the cockpit. “Is anyone alive?” he shouted. He had come by van as far as the perimeter fence and then run through the gap left in the defences by our plane.

Our mouths were stuffed with half chewed chocolate. We were incapable of coherent speech. I tried to say “Don’t worry, we’re OK”, but it was ring the stretchers – they’re alive. I can hear them groaning”, shouted the C/O. Doug and I collapsed. We were laughing until the tears came and doing the nose trick. It was all very silly really. Of course, next day, when it came round to seeing what had happened to the squadron that night, things were different. Doug said to me pretty solemnly “Look Mike, if you’d flown with Alan Heitman last night, he’d be alive now and I’d be dead”.

I’ll mention one other story about the heavy boys. A Lancaster was shot up and its hydraulic system was punctured. One of the air gunners botched up the fractures with first aid dressing and chewing gum – but a lot of oil had been lost. He topped up the system with coffee from the thermos flasks; then all the crew peed into the thermos and they added that. They had just enough pressure to work one gun turret and they managed to repel an enemy night fighter. Over base, they decided to try to land. They landed, rather soggily, with the under cart only half extended and locked, on a mixture of oil, urine and coffee.

I’d always wanted to bale out. Years later, I even wrote to Jimmy Saville asking Jim to fix it for me to bale out and be scooped up by a helicopter. I told my form at school that it was my secret ambition. One boy said “I’ve decided to write to him too and to say my secret ambition is to see a Latin Master bale out – and his parachute fail to open”.

BUT why did we risk death to save our planes? Why did we join the most perilous and casualty ridden branch of the forces? Why did we refuse to turn back when instruments failed? Were we just conditioned lemmings? I don’t think so. Some of it was competitiveness, a bit was bravado; but most of all, it was genuinely pride of performance; the Olympic ideal, the pursuit of excellence.

I can’t believe that was bad. Personally, I am happy to have been part of it.

A tour of operations was 30 for the heavies who bombed at 15,000 to 18,000 feet; 50 for Mosquitoes who bombed at 25,000 feet that were much less vulnerable. When Doug and I had done 48 raids we transferred to another squadron, hoping to do 98 raids on the trot. In fact, when we had done 52 raids the war in Europe ended. We volunteered for Japan as a crew and while we were on embarkation leave, the atom bombs were dropped. Doug went back to Melbourne and seven months later, his son was born. 10 years later he was killed in a routine civil flying accident.

You can see an interview with Mike Bayon below

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

‘Well you see, Norm, it’s like this. . . A herd of buffalo can only move as fast as the slowest buffalo. And when the heard Is hunted, it is the slowest and weakest ones at the back that are killed first. This natural selection is good for the herd as a whole, because the general speed and health of the whole group keeps improving by the regular killing of the weakest members. In much the same way, the human brain can only operate as fast as the slowest brain cells. Now, as we know, excessive intake of alcohol kills brain cells. But naturally, it attacks the slowest and weakest brain cells first. In this way, regular consumption of beer eliminates the weaker brain cells, making the brain a faster and more efficient machine.

And that, Norm, is why you always feel smarter after a few beers.’

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

He bailed out and with every heartbeat he could see a gush of blood from his

severed foot and at that height and in that cold thin air, the blood spread out

almost pink in curious shapes and spirals, rather like a long sinuous scarf. He

decided not to pull the ripcord yet or he would have bled to death before he

landed.

He bailed out and with every heartbeat he could see a gush of blood from his

severed foot and at that height and in that cold thin air, the blood spread out

almost pink in curious shapes and spirals, rather like a long sinuous scarf. He

decided not to pull the ripcord yet or he would have bled to death before he

landed.

Old Fashioneds, (1½ oz Bourbon, 2 dashes Angostura bitters, 1 sugar cube,

dash water) certainly one Horse’s Neck (2 oz Bourbon, 3 oz ginger ale, 3

dashes Angostura bitters, lemon garnish) , a Sidecar (1½ oz cognac, 1 oz

Cointreau, 1 oz lemon or lime juice, sugar on glass rim) and a Lizard’s

Breath, some Manhattans (2 oz Canadian Club, 1 oz sweet vermouth, dash

Angostura bitters, garnish with Maraschino cherry), an Alexandria and a

Singapore – oh and a few others.

Old Fashioneds, (1½ oz Bourbon, 2 dashes Angostura bitters, 1 sugar cube,

dash water) certainly one Horse’s Neck (2 oz Bourbon, 3 oz ginger ale, 3

dashes Angostura bitters, lemon garnish) , a Sidecar (1½ oz cognac, 1 oz

Cointreau, 1 oz lemon or lime juice, sugar on glass rim) and a Lizard’s

Breath, some Manhattans (2 oz Canadian Club, 1 oz sweet vermouth, dash

Angostura bitters, garnish with Maraschino cherry), an Alexandria and a

Singapore – oh and a few others.

Radar. Within a couple of minutes of take-off, this always came on. (On the

first flight you think “My God – they know we’re coming”. It reminds me of the

new air gunner who said excitedly to his battle worn pilot “Skip, Skip they’re

firing at us”. “I know” came the weary reply, “they’re allowed to).

Radar. Within a couple of minutes of take-off, this always came on. (On the

first flight you think “My God – they know we’re coming”. It reminds me of the

new air gunner who said excitedly to his battle worn pilot “Skip, Skip they’re

firing at us”. “I know” came the weary reply, “they’re allowed to).

pay and in any case the ground crew all treated me as an officer and I saw no

point in going on a course to learn to behave like an officer. I said I hadn’t

time, I was busy. “All right” he said “You can skip everything. We’ll bypass it

by saying you were commissioned on the battlefield”.

pay and in any case the ground crew all treated me as an officer and I saw no

point in going on a course to learn to behave like an officer. I said I hadn’t

time, I was busy. “All right” he said “You can skip everything. We’ll bypass it

by saying you were commissioned on the battlefield”.