|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

Pedro’s Patter.

Excerpt from Jeff’s book – Wallaby Airlines.

On Thursday, Dick Brice and I, with ‘Bugs’ Rose and ‘Blue’ Campbell as crew members, set off for Nha Trang to take over from the crew who had been there since Saturday. We would be relieved in turn the following Tuesday. Dick and I were both qualified captains, but squadron procedure called for pilots to see difficult airfields from the right-hand seat first, before operating as captain into those fields. I was the new boy on this detachment so, although sharing the flying, Dick would fly into the difficult airfields.

Both of us were ‘hour hogs’, but for different reasons. Dick had ideas of later joining an airline. I had taken two years off flying duties to complete a degree and wanted to catch up to my contemporaries. And so we were both keen to log as much flying time as we could in Vietnam. The detachments provided an ideal opportunity. While away from Vung Tau, we were virtually our own masters. No limits had been placed on us, and we could therefore accept as many tasks from our USAF coordinators as the limits of daylight, weather and fatigue would allow. Most of the squadron pilots, being young and keen, felt the same way. This willingness to fly had given the squadron a ‘can-do’ reputation among the Special Forces for getting the job done, even under difficult conditions; a reputation which many US squadrons, operating ‘by the book’ as they would in the States, did not enjoy.

|

||

|

|

||

|

It is hard to imagine a handful of aircraft and crews gaining such a reputation amongst the huge airlift effort of the USAF and US Army, but the backslapping welcome we received everywhere from the Special Forces proved the point. Some of our loadies must have wondered why their pilots were so obsessive about logging flight time. It made no difference to them how much they flew since their main job was on the ground. But they did not complain when we talked them into one more sortie. Bugs was enthusiastic and capable, and did everything he could to help us along, while the taciturn Blue took it all in his stride.

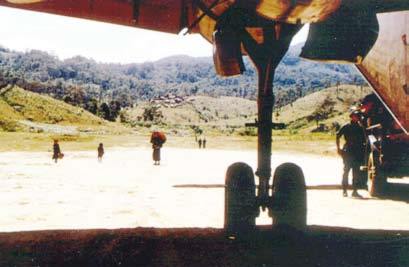

Our detachment tasks were unscheduled resupply missions to any one of dozens of small Special Forces camps from the two main supply bases in the II Corps Military Region, Nha Trang and Pleiku. These camps were scattered throughout the mountainous region to the west and north-west of Nha Trang. Each camp had its own rudimentary airstrip. Some were short, narrow and rough, and suitable only for Caribous, light aircraft and helicopters. Others were longer, with PSP or T-17 membrane surfaces suitable for larger aircraft. Many were perched on top of a hill, or squeezed into a narrow valley, requiring full STOL performance from the Caribou.

The weather today was overcast turning the sea a steely grey. On our way north, the port engine began running roughly. Not wishing to spend a six-day detachment plagued with engine trouble, we diverted back into Vung Tau to have it checked. Once at Nha Trang the engine began playing up again. Bugs had already cleaned the plugs, so he decided to replace them with the spare set we always carried. Still the engine coughed and backfired when we checked the magnetos. As a last resort, Bugs changed the high-tension leads, and at last the engine ran sweetly. By this time, it was mid-afternoon. We called up TMC and were given our first and only task for the day, a load for Plei Me.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Plei Me was a Special Forces camp 110 miles north-west of Nha Trang. The Caribou was the largest fixed-wing aircraft that could get into its 1200-foot length. It was definitely a Type 1 airfield. Only RAAF Caribous went into Plei Me. US Army Caribous did not. This made us very popular with the Special Forces team there, and they were always trying to coax us to do extra sorties for them. Since Plei Me was not only short, but also 1200 feet above sea level, it was marginal, even for a Caribou. Dick, who had been there only a few times himself, flew this sortie. He was soon in a lather of sweat, the wet patch on the back of his flying suit spreading as he manhandled the aircraft down to touch down on the first hundred feet of the strip. From finals, the strip looked impossibly short, since it had a hump in the middle, and you could not see the other half until you were rolling down the runway after landing. It was a case of psyching yourself into believing that there really was an adequate strip there, and doing all the right things to pull up before you ran off the other end.

On the ground Bugs and Blue, sweating profusely in the muggy heat, helped the Special Forces team push our cargo of three 1500-pound pallets of boxed food onto the tray of a battered army truck, backed up with its tailgate almost against the Wallaby’s cargo ramp. There was nothing as sophisticated as a forklift way out here. Behind us, the red and yellow South Vietnamese flag fluttered bravely over the sandbagged trenches and makeshift timber and galvanised iron buildings that constituted the camp. With only an hour until last light, we wasted little time on pleasantries. The dust from our landing had barely settled when Dick had the first engine turning as the truck pulled away with the last pallet.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Buddha was vermilion in the setting sun as we joined the circuit at Nha Trang. The outskirts of the base merged with the horizon, rapidly darkening in the short tropical twilight, revealing only the featureless bulk of the nearby mountains and the stark rectangles of the VHF ground communications antennae that transmitted telephone conversations from base to base in the absence of secure landline communications. We finished our post-flight paperwork sitting on the cargo ramp, drinking cans of Budweiser beer from the TMC fridge. Next day, we had two long runs. The first, which I flew, was north of Pleiku to Plei Mrong, a 3000-foot PSP strip. The other was to Dak Pek, further north again and was Dick’s sortie. Dick had told me over the previous night’s Budweisers about ‘the dreaded Dak Pek’. When we got there, I could see what he meant. The camp and strip were in a mountainous river valley six miles from the Cambodian border, and close to the notorious Ho Chi Minh Trail. The Aerodrome Directory warned: ‘Check SF for security. Airfield usually secure sunrise to sunset. VC on hills to west’, encouraging us to use our defensive spiral descent. As we spiralled down, I gazed up at the jungle-shrouded ridgelines above us, wondering whether a VC was looking at us down the barrel of a gun.

Several months later I was to find out. Descriptions do little

justice to Dak Pek airfield. Although not the shortest strip our

Caribous went into, it was certainly one of the worst. It was Type 2

for Caribous. The 1400-foot dirt runway, 2350 feet above sea level,

ran along the narrow valley within a bend in the river, and on the

only flat area around. On one

The approach to one end of the strip was over a steep, timbered hill; to the other end over the river towards a claustrophobic cutting through which the strip passed. Dick had been there only once before, as copilot. Now he was sweating it out himself, as I would be next time. It was obvious that time for another sortie today was running out so, after unloading, we accepted the offer of a cup of coffee with the team. It was a stiff climb to the camp, which had a grandstand view of the surrounding valley, a very desirable attribute in this part of the country.

Montagnard children, the smaller ones completely naked, played on a discarded artillery piece, waiting for their fathers and older brothers to return from scouring the nearby mountain trails looking for VC. Montagnard women trudged by, large urns on their heads, on their way to collect water from the river. Sitting around a rough trestle table in their ramshackle command hut our Special Forces hosts quizzed us about the war. What a joke! We knew as little as they did. Although we picked up snippets of information as we moved around the country, we had to rely on week-old Australian newspapers or dial up Radio Australia on our HF radio to give us an overall picture of what was going on.

You have to be fifty-nine to believe a man is at his best at sixty.

I did not envy the Special Forces teams. There were usually about a dozen men in each camp, all highly trained in hand-to-hand combat and weapon handling. Although they were officially classified as ‘advisers’, in places like Dak Pek they were organised on company lines, the senior man, usually a captain, acting as company commander and directing all activities. His men acted as platoon sergeants to groups of Montagnards drawn from the village population. They lived under primitive conditions, and were absolutely dependent on aerial resupply for not only ammunition and materials, but also food and any creature comforts they enjoyed. It was no wonder they cultivated our friendship, and offered us hospitality, reliant on us as they were for bringing in everything they needed on a day-to-day basis.

As dusk was again approaching we had to end the conversation and get back to Nha Trang. After dinner, Dick and I decided to look for the Buddha, which we had seen so far only from the air. We set off downtown in our scrounged and battered vehicle, a Ford F-100 automatic pick-up, which had large rust holes in the cabin floor and tray, and an ominous noise in the transmission. The truck had an interesting history. Apparently it had been on its way to the scrap heap, but was somehow diverted when a smooth-talking Aussie crew chief persuaded a US Army drinking buddy to look the other way. Since then it had been passed on to successive Nha Trang detachment crews, who had appreciated the independence of having their own transport away from base.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Nha Trang looked cleaner and more sophisticated than Vung Tau did, and less symmetrical due to its position astride the river estuary. It was also more expensive, thanks to the Yanks. We passed the grand-looking entrance to the Vietnamese Air Force Academy, an archway topped with a huge bronze eagle. Inside the grounds a World War II Bearcat fighter was set up on a pylon as an ornament on the lawn. The choice of aircraft seemed inappropriate. The fledgling Republic of Vietnam Air Force (VNAF) flew mainly retired USAF Skyraiders and C-47s. As far as I know the Bearcat was never part of their operational line-up. Freedom Fighter jets, their first new aircraft, were presently being introduced at the Bien Hoa fighter base near Saigon under a US assistance plan. The Buddha, whose white bulk stood out like a beacon from the air, eluded us among the side streets of the city. We gave up, and decided to explore the town instead. We parked the truck and wandered down the main street. As at Vung Tau, military uniforms rubbed shoulders with ao dais. Trishaws and Lambrettas dropped off American GIs and rushed away with another fare.

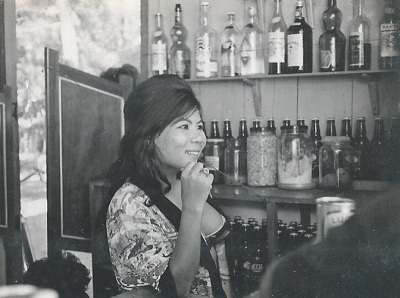

An old lady at a mobile food cart tried to tempt us with some

savoury meat on a satay stick. The aroma of her cooking lingered as

we walked into one of the many bars, our eyes momentarily blinded in

the soft reddish light inside. A bargirl quickly appeared from

behind a lurid, beaded curtain. Her slim, attractive figure was

vulgarised by

Retrieving the truck, we managed to find our way back to our

quarters at the MACV compound. In spite of its pleasant location on

the beachfront, the compound offered few creature comforts. Dick and

I had to share an austere room equipped only with two beds, sheets

and mosquito nets. We soon gravitated back to the bar, which had

tables and chairs, a few poker machines and the prospect of

conversation, although none of the Americans we came into contact

with at the base lived in this mess. We struck up a conversation

with a couple of civilian engineers who came

Next morning, like all mornings here, we had to face another American-style breakfast. We joined the crowd shambling past the servery in the cafeteria-style dining room. Regardless of my indications or protestations, I seemed to get the same each morning; two hard fried eggs ‘sunny side up’, several pieces of overdone bacon glued together with fat, a ‘stack’ of pancakes, with the whole lot floating in a sea of maple syrup. As I looked at this gastronomic nightmare, my stomach churned but I was too hungry not to eat it.

On the bright side, today the flying was all mine, and I was looking forward to it. TMC ran over the day’s activities with us. We had ammunition for Plei Me and building materials and POL for Tuy Hoa South. Getting into Plei Me was interesting, as I had to descend through a minute hole in the cloud cover in a very tight spiral, avoiding swarms of choppers taking part in a heliborne assault operation. Dozens more were parked in lines each side of the short, narrow strip, making the landing even more difficult. A mixture of ‘Huey’ gunships and troop carriers, they refuelled from huge rubber fuel cells brought in from Pleiku by Chinook (heavy helicopter). The air was full of dust stirred up by their rotor blades, and the characteristic wokka-wokka sound mingled with the intermittent rat-a-tat of distant gunfire.

Growing old is hard work. The mind says "Yes" but the body says "what the hell are you thinking."

The busy Special Forces team had our load of ammunition onto the truck and into the choppers in a few minutes. We were truly part of the action here My first landing at the minute Plei Me strip was an anticlimax. As I recorded in my diary: ‘I managed to hack it ie. We’re still alive, even though some fool Yank parked too close to the strip.’ Just off the end of the runway at Tuy Hoa was a wrecked C-130. A C-123 pilot told us that the pilot of the C-130 had misjudged his approach, and overrun the short PSP strip, becoming bogged in the soft sandy soil. As the unfortunate, but at this stage undamaged aircraft, was interfering with the approach path on the other runway, the Army colonel running the base ordered it towed away. After two abortive attempts, during which the nose wheel assembly was ripped off and the fuselage skin torn and wrinkled, the next instruction was to push the C-130 away with a bulldozer. This operation was successful, that is, in removing the forlorn aircraft, but the end result was an eight million-dollar pile of scrap metal. The hulk remained there for months until it was blown up to make way for a new runway. By contrast, on the rare occasions when an aircraft in our shoestring operation came to grief, it was carefully put back together with salvaged or improvised bits and pieces and returned to service as soon as possible.

Sunday was Dick’s day but the weather, quite good until now, finally stopped us. We were unable to get into Plei Mrong, its valley being socked in with low cloud. This forced us into nearby Pleiku on a GCA (Ground Controlled Approach). Wondering what to do for the rest of the day, our interest quickened when the GCA controller told us to drop our load and proceed to nearby Holloway to pick up some travelling entertainers waiting for a lift to Tuy Hoa. Expecting buxom showgirls, we wasted no time getting airborne again, but were disappointed to find a troupe of male folk singers waiting for us at Holloway. As we found in the coming months, many entertainers, sponsored or giving their services free, visited Vietnam regularly.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Several well-known Australian personalities performed for us at Vung

Tau and for the troops at Phan Rang, Lorrae Desmond and Dinah Lee to

name a couple. After dropping off our folk singers, we continued on

back to Nha Trang for our next assignment. Later in the day, we were

given a load for Qui Nhon, and instructions to return via Tuy Hoa to

pick up the folk singers. Since Tuy Hoa was also on the coast we

took the opportunity to fly up low level, enjoying the coastal

scenery. The seafront here is very rocky, with many inlets and small

islands. On one rocky promontory stood a large lighthouse and what

looked like a monastery. Many small craft dotted the blue waters,

fishing the coastal shelf. Qui Nhon is a large port city in the area

then known as I Corps Military Region (colloquially ‘i’ Corps), the

northernmost part of the country. Many warships and freighters were

tied up in the harbour. A large Catholic Church dominated the

landscape from its position on a hillside. After dropping our load,

we returned once more low level along the coast. Ten miles north of

Tuy Hoa, the main highway and railway from Qui Nhon meet the coast

and parallel it for the rest of the way to Nha

It was nearly six o’clock when we saw the Buddha again. Another long day. After dinner, there was entertainment in the MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam) bar—Sunday special. A local rock group performed. The electric guitars, the showbiz clothes, the mop heads and the accents—all were pure Beatles. Only the Asian faces broke the illusion, and seemed oddly incongruous in the American club atmosphere where no other Vietnamese were present. But they put on a good show. An Australian girl named Shirley, who sang some impromptu songs, followed the Viet Beatles. Our Texan friend informed us: ‘She’ll do a strip show if the price is right’. I am not sure where Shirley, or the Texan’s information, came from.

Monday was my day again. We dropped Bugs and Blue at the Special

Forces ramp, as usual, before driving down to Ops to submit our

flight plan. As we drove back into the ramp, we witnessed a sight

which was more like a scene from a hillbilly western. At the back of

the Wallaby was a forklift, its prongs level with 17 50 Cow at Nha

Trang 51 The Elusive Buddha the cargo ramp, and supporting a wooden

cage. Inside the cage was part of our cargo, a mournful-looking cow.

The forklift driver, a diminutive Vietnamese wearing a crash helmet

with his black pyjamas was, with characteristic Asian patience,

trying to get the cow from the cage into the aircraft. He was having

little success. The cow seemed unwilling to forsake its cramped cage

for the unknown perils of the Wallaby, particularly when, on its

first tentative step, it

Van Canh, reasonably long at 2000 feet, was wedged in on both sides by steep mountain ranges. I misjudged the first approach and, playing safe, went round for another go. The next approach was much better and after landing I parked beside a US Army Caribou already on the ramp. Now came the sequel to the loading story. Bugs opened the cargo ramp fully, which angled it down about 30 degrees towards the ground. The cow seemed to have overcome its distaste for the aircraft, and now wanted to stay inside. Bugs’ solution to this problem was to hand the end of the tether rope outside to a Montagnard soldier waiting to claim this food on the hoof. Bugs repeated his famous bellow, and gave the cow another kick on the rump. The unfortunate animal lurched forward, stepped onto the sloping ramp, immediately lost its footing and slid the rest of the way on its rump. Picking itself up after this undignified exit, the cow found itself in the open looking at the surprised Montagnard meekly holding its rope. The Montagnard, reading the cow’s terrible expression, turned to run, a little late. The enraged animal leaped forward, head lowered, until its horns, which fortunately had been clipped, found the retreating soldier’s buttocks. This produced a burst of speed from him, further encouraging the cow. And so it went on until both disappeared from view.

After another less eventful run to Van Canh, we were sent on a mail

run-type mission through three bases in central II Corps—Buon Brieng,

Phan Rang and Cam Ranh Bay. Buon Brieng was another membrane strip.

The runway and parking ramp were covered with the nylon-coated

matting which, after a shower of rain, was very slippery. Having

skidded slightly when taxiing the Caribou into the sloping ramp, I

watched with concern as a jeep, zooming out from the nearby compound

to meet us, went into a four-wheel drift towards our aircraft. The

driver, cursing and swearing, cranked the steering wheel in both

directions until the vehicle at last responded, and the potential

disaster was averted. A Special Forces lieutenant invited Dick and

me up to the camp for coffee while the crew finished unloading. I

got the impression he wanted us ‘fly-boys with cushy jobs’ to see

how the war was really fought, though all we c

The detachment ended quietly on Tuesday morning with a run to a place called Tan Rai. Here, the village had been fortified in a pentagonal arrangement of sandbags and slit trenches, looking like a copy book example from the Special Forces manual, if there was such a thing. The captain, a sandy-haired Virginian, was especially pleased with our cargo of hessian bags and roofing iron. The Special Forces team was expecting trouble and was in the process of sandbagging their quarters and digging more bunkers. On return to Nha Trang, we handed over to the incoming Wallaby and continued home to Vung Tau. The six days just ended had been full of interest for me. I had seen new places and people, flown into challenging airstrips in difficult weather and carried an amazing variety of cargoes. Better still I had added 41 hours to my logbook. Our reception everywhere had been gratifying, with our Special Forces allies lauding our efforts to get supplies to them. Whatever else I felt about being in Vietnam, at least I was doing something useful!

|

||

|

I don’t feel my age. In fact, until midday I don’t feel anything at all, then it’s time for my nap!

|

||

|

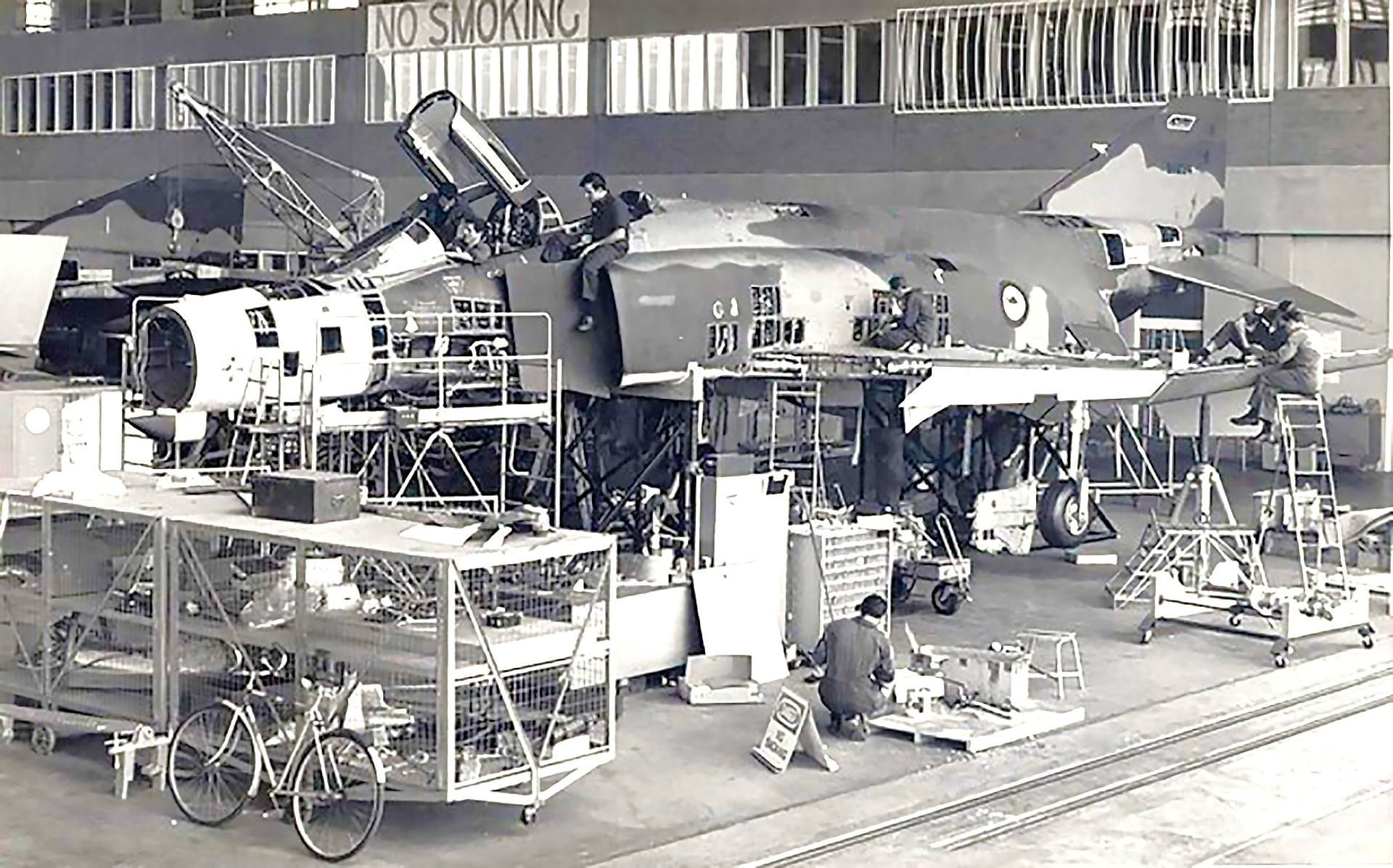

RAAF F-4E A69-7234 Arrestor Cable Accident.

This account is paraphrased from "Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service" by Stewart Wilson. The account was excerpted from the official Court of Inquiry report.

On 19 October 1970, FLTLT J.L. Ellis, pilot and FLTLT E.B.J Bolger, navigator, conducted simulated bombing and strafing attacks on the Evans Head bombing range. During the sortie the F-4E's left generator dropped off-line and the bus tie-in failed to function properly. The pilot elected to return to Amberley and a "Pan" was declared.

With experienced Phantom instructors in contact from Amberley tower the unserviceability was confirmed. As a result of the U/S, brake anti-skid and nose wheel steering were lost. With a 15 knot crosswind Ellis elected to carry out an approach and engagement of the arrestor wire.

In the interim the Arrestor System Servicing Team checked the whole arrestor system including the tension of the pendant cable, the pre-tensioning device, and the position of the rubber cable supports. The system appeared serviceable.

With a final approach speed of about 147 knots the aircraft touched down on the centre line about 500 feet short of the arrestor cable. The hook engaged the cable and, almost immediately after engagement, the cable on the starboard drum broke and the remaining piece and shock absorber unit, were dragged along the runway after the aircraft.

The cable slid through the Phantom's arrestor hook until the swaged end fitting on the starboard end of the pendant came to rest against the hook. The F-4E then yawed to starboard, the arrestor hook broke off the aircraft and the starboard arrestor system and remaining cable continued under the Phantom at high speed. The shock absorber flew around the front of the rack under the port wing and then continued back between the port weapon pylon and the port 370 gallon drop tank, rupturing the tank. The remaining cable wrapped around the port undercarriage strut and broke into pieces as the port wheel ran over the cable.

By this time the aircraft had yawed approximately 60 degrees to starboard and continued to slide along the runway. The pilot tried to straighten the aircraft and had almost succeeded when it left the runway. The port wheel then sank into soft earth and the Phantom yawed violently to port through about 80 degrees. The starboard and nose wheels collapsed and the aircraft came to rest about 2,500 feet from the end of the runway and 200 feet off the runway on the starboard side.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Court of Inquiry found that "... the aircraft was flown into the arrestor system with considerable skill." and the immediate cause of the accident was "... the fracture of the arresting system cable at the western brake drum, which in turn caused the aircraft to skid out of control until the undercarriage collapsed. The cause of the fracture of the cable was a culmination of: having the pickup point of the cable on the drum too close to the flange plate thus making it easier for the cable to whip across the top of the flange; having too much slack cable between the brake drum and the shock absorber, thus enabling the cable to have excessive random movement near the drum; and the wedging caused by the cable being forced under the outer layers of the coils of cable."

The Phantom's front fuselage, starboard wing, and port and nose undercarriage were deemed unrepairable and she was assessed as having suffered "Category 4 damage - repairable at depot or contractor." The challenge was accepted by No 3 Aircraft Depot and work began in early February 1971 in No 482 (Maintenance) Squadron's hangar. The team of 20 was led by SQNLDR C.M. "Avro" Anson and WOFF B.H. Morley.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Work was completed in September 1971 after expending 18,750 man hours with 3AD manufacturing special fixtures and handling equipment.

A69-7234 was again flown on 30 September 1971 and rejoined No 82 Wing's Phantom force. The aircraft was returned to the US in 1972, but a replica of her was presented to the RAAF Museum in 1989 and painted in 234's RAAF colours. She was "3AD's Phantom" - hearty congratulations to the "Depot Doggies"!

|

||

|

|

||

|

Never irritate a woman who can operate a backhoe.

|

||

|

DVA Christmas get together.

All pics names L-R. You can click some for the HD version.

Around this time every year, the Queensland head office of DVA (in Brisbane) holds a function where members of various ESO’s are invited to attend, to have some Christmas cheer and to mingle and meet with the various heads of departments in the DVA. It is also an opportunity for the DVA staff to wind down a bit after another hectic year and to meet with and put faces to some of the names they have dealt with during the year. It’s an enjoyable win win situation. The function is normally attended by a senior officer of the DVA in Canberra and this year the very approachable Elizabeth “Liz” Cosson, AM, CSC, the Deputy Secretary/Chief Operating Officer, made the journey to Brisbane and made herself readily available for a chat with all present.

Liz, who has only recently taken on the position with DVA, is eminently qualified for the job. She currently holds a Graduate Diploma in Management Studies, a Bachelor of Social Sciences and a Master of Arts in Strategic Studies. She joined the Australian Army in 1979 as an officer cadet and was commissioned into the Royal Australian Army Ordnance Corps. In 1991 she was appointed to a position at the RAAF’s Logistics Command where she was responsible for the support to army aviation aircraft. For her work in improving the availability of the Blackhawk helicopter fleet and supporting the fleet deployment to Cambodia, she received a commendation from the Air Officer Commanding Logistics.

In 1995, after graduating from the Staff College at Queenscliff, she was promoted to Brigadier and served in a number of appointments within Land Command. These included Logistics Staff Officer with 11th Brigade where she was involved in support planning for the 1999 operations in East Timor. In November 1999, she was appointed Chief of Staff of the Peace Monitoring Group in Bougainville, PNG. For these later activities, she was awarded a Conspicuous Service Cross (CSC) in the 2001 Australia Day Honours List.

On her return from Bougainville she was seconded to the Joint Standing Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade in the House of Representatives. In November, 2007 she was the first female to be promoted to the rank of Major General (that’s AVM in the real money – tb). After an extraordinary and satisfying career, she retired from the Army in October 2010 and joined the DVA as the First Assistant Secretary of the Client and Commemorations Division at the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

She was appointed to the role of Deputy Secretary, Business Services Group with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection in November 2012 to October 2014 then from October 2014 to May 2016 she was with the Commonwealth Department of Health as a Deputy Secretary, Chief Operating Officer. She returned to the DVA in May 2016 in her current position.

On the 1st April this year, Leanne Cameron returned to Queensland, this time as the Deputy Commissioner, Queensland.

Leanne’s public service experience spans a range of policy, service delivery and project management roles. She joined the Department of Veterans’ Affairs in 2001 as a graduate, working in Human Resource Planning and Industrial Relations before transferring into Health Policy, where she worked until she left the Department in 2009. After a couple of years in the private sector and local government, she returned to DVA, taking up a position in the Health team in Brisbane.

Prior to her current appointment, Leanne was the National Director for the Veterans’ Access Network, and most recently the Deputy Commissioner for South Australia and the Northern Territory. She was responsible for implementing the on-base advisory service, and the Department’s national contact centre. She was also responsible for Community Development, FOI and Case Coordination.

In 2010 she undertook a six month exchange program with Veterans’ Affairs Canada, working on a transformation agenda for their health program. In 2011 she received a Secretary’s Award as a member of the small team responsible for responding to the devastating floods in QLD and last year received a DVA Australia Day Award for her work in redefining DVA’s approach to service delivery.

She has qualifications in Public Administration and Policy, and Organisational Psychology.

|

||

|

Liz Cosson, Leanne Cameron.

|

||

|

Today the DVA employs around 2000 staff throughout Australia and they look after 316,000 veterans and their dependants at an annual cost of $12.1 billion dollars. They have offices located in each state and territory capital, as well as smaller regional offices, known as Veterans’ Affairs Network (VAN) offices. They provide information, advice and advocacy services and contrary to some believers, staff do not attend classes on how to reject claims. We always found the staff at DVA to be extraordinarily helpful and they go out of their way to help the Veteran Community.

DVA staff are bound to administer the Act – if you have a disagreement with DVA, don’t take it out on the staff, they are just doing their job, take it up with your Federal Member, they are the ones who set the rules.

As at June 2016, there were 145,955 Gold Cards on issue and 56,164 White Cards.

Others present at the get Christmas get together were the following:

|

||

|

Amanda Green and Bryan “Chips” Ross.

|

||

|

The very capable Amanda is the Executive Assistant and gate keeper to the Deputy Commissioner. She has been with the Department for a number of years and knows her job inside out. She is always available, willing to help, always sporting a big happy smile and some say the Queensland office wouldn’t be the same without her.

Chips, an old RAEME who worked on the Army’s Centurion Tanks, is the President of the Atomic Ex-Servicemen’s Association. This Association, which was incorporated in 1985, is an independent Organisation formed by Veterans who have been acknowledged as participants in the British Nuclear Test Programme here in/on Australian Territory, during the 1950's and after. The main objective of the Organisation is to find and assist any qualified person, whether of the Armed Forces or Civilian, in their pursuit of recognition for their Service. For more information, visit their website HERE.

|

||

|

Jennifer Robertson with the People’s Champion, John “Sambo” Sambrooks.

Jennifer is the recently appointed Chair of the Queensland Defence Reserves Support Council (DRSC), having been appointed on the 22nd June 2016. The DRSC promotes the benefits of Reserve Service and encourages employers and the community to support Reservists. It is part of the Defence portfolio and functions in an advisory capacity.

Jennifer is an extremely qualified person with a wealth of experience as a lawyer, company director and currently holds diverse business board memberships. You can get addition information on the DRSC HERE.

Everyone knows Sambo – the Honourable Secretary, Treasurer and at times bottle washer of the RTFV-35Sqn Association.

|

||

|

Dianne Pickering, Carol McCool.

|

||

|

The effervescent Di needs no introduction, a short while ago she was the President of the Queensland Branch of the WRAAF Association but these days she helps husband Doug run the 2 Squadron Association in Queensland.

Carol, who was Carol Karkeek when in the WRAAF, is the current President of the Qld Branch of the WRAAF Association. Carol was elected and took over the Presidency of the Association at the 2016 AGM, and some say a good thing too.

These two girls worked together at Fairbairn all those years ago.

|

||

|

I know my secrets are safe with my friends, because at our age they can’t remember them either.

|

||

|

Greg Ross, Lisa Baisten, Ben Isaacs.

These three people volunteered their time, (in the military fashion??), to ensure everyone was well and truly catered for and had the odd cooling ale when needed. It’s been said they were possibly the three most popular people in the room, and who could argue with that?

Greg Ross is the Assistant Director – Rehabilitation and Benefits and looks after all things Compensation.

Lisa Baisden is the VAN Forecasting and Scheduling Manager – Veterans Centric Client Contact Support. If you ring the Vets Client Support department from anywhere in Australia, your call will be answered by someone in Lisa's department.

Ben Isaacs is the Assistant Director – Client Access and Support and looks after the VAN’s, On Base Advisery Service (OBAS) and Community Support for Queensland. OBAS is a very important section and provides a DVA presence on more than 40 ADF bases nationally and offers members information and advice about the support and entitlements that they might be able to receive though DVA

|

||

|

Marion Milne and Phil Lilliebridge.

Marion is the manager of the Veteran’s Access Network (VAN) in Queensland. The VAN offices are like a mini DVA Capital City office and can:

If you’re looking for a VAN office, see HERE.

Phil is an ex-Army officer and served as 2/IC with the 2/14 Light Horse Regiment in Iraq back in 2006, though a few have told me they’d love to see him try and ride one…… Phil is currently the Senior Vice President of the Kedron Wavell RSL Sub-branch.

|

||

|

Frank McCosker and Dianne Pickering.

|

||

|

Frank, who is a spritely 94 years and a few days old, served with the Army during WW2. In August 1942, as a 19 year old Sergeant leading a bunch of blokes, (just think about that for a minute or two – tb) he was with the 9th Battalion, 7th Brigade which fought the Japanese at Milne Bay in PNG. He discharged from the Army at the end of hostilities with the rank of Lieutenant and joined the Queensland Police Force in which he served for 33 years. He retired from the Police Force as a Superintendent in 1980 and as he said, “has enjoyed life ever since”.

We asked Frank about his time in the Army and about the war. He said "I grew up north of Brisbane, in the Glasshouse mountains. I left school at 14 and was just 16 when, in April 1939, I joined the Army. There was a big recruitment drive on early in 1939 as the writing was on the wall. My brothers joined as did most of our cricket and soccer team. When I got up near the sign on table I realised I was too young, so I walked outside and then walked back in again 12 months older.

We knew the Japanese intended to occupy Milne Bay and use its three airstrips to support their troops on the Kokoda Track, that couldn't be allowed to happen. Our blokes left Townsville on the 12th August in 1942 and got to Milne Bay late on the afternoon of the 16th. We knew two convoys of Japanese had already left Rabaul and were headed for the bay

Our blokes had got there first and we set up our Bren guns and Vickers machine guns at one of the airstrips where we thought the Japanese would try and attack. We were waiting. At about 3.00am it started - up went the flares and all hell broke loose. The Japs yelled, 'It's no good. We're coming across!' Someone on our side yelled back, 'Like bloody hell you are'. They attacked straight into a wall of flying metal. After a while they pulled-back, formed-up and attacked a second time and then a third time. It was a sight one would never wish to see again. Arms, legs, heads, body bits everywhere.

The Japanese then shifted the direction of the attack but were again cut to pieces. They decided to go up and around the airstrip and walked into more of our prepared positions and got another flogging. Then at about 8.00am they stopped

Our forces then went on the offensive at the airstrip and were fired on by snipers. Then some Japanese soldiers stood up among the dead and fired. We made sure everyone was dead after that.

The Japs murdered 57 indigenous people and 33 Australian troops. An inquiry was later held into the actions of the Japanese at Milne Bay, it listed the sexual mutilation of natives, males and females, who were staked out, raped, bayoneted and disembowelled. It wasn't pretty and after what I'd seen at No.3 airstrip, death never worried me after that and I saw quite a bit of it.''

It was left to the British Field Marshal, Sir William Slim, to put the battle in perspective. "Australian troops at Milne Bay had inflicted on the Japanese their first undoubted defeat on land ... some of us may forget that, of all the allies, it was the Australian soldiers who first broke the spell of the invincibility of the Japanese army.''

Frank's final campaign was in Borneo where he took part in the landing at Balikpapan. It was in Borneo, he says, that he "forgot to duck''. "I got hit in Borneo. I took an ambush patrol out and, on dark, down came some Japs. I had nine men with me, mostly with automatic weapons and we went zap! We knocked down most of them, 16 or 17 I think and I got some shrapnel in the back, probably from a grenade.''

When the Japanese surrendered, McCosker joined the Occupation Forces and went to Japan for three years.

"We were near Hiroshima and the atomic blast had broken all the windows of the place we were in. There was nothing much left of Hiroshima.'' he said.

Although 94 years old, he still has an eye for a pretty girl and we noticed had a firm grip on Dianne and was very reluctant to let go.

A remarkable man and if I’m as good as he is at that age I’ll be very happy.

|

||

|

Peter Schwarze, Jennifer Robertson, John Sambrooks.

Peter is a member of the SAS Association which has branches in all States, except for Tasmania. Its aims are:

A fundamental objective of the Association is to provide a forum for members to stay in contact with each other and to provide them with information on Association activities and up-to-date news items. Their website (HERE) was developed for that purpose and it is intended to complement Rendezvous, the Association's national magazine and the State Branch newsletters. In addition, ASASA conducts a variety of social and commemorative events at State and National level for its members.

A second ASASA objective is to provide support and assistance to members and their dependents, as required. This support includes provision of assistance to members in preparing applications to DVA to claim welfare entitlements and the provision of advocacy support to appeal DVA decisions that reject members' claims. Support is also available to assist members in preparing application to the SAS Resources Fund for assistance. At the National (and State) levels ASASA is involved with Government and Government departments in furthering veterans' welfare entitlements.

Lastly, the Association supports SASR when and as necessary and works to protect the Regiment's reputation and good name. This includes assistance in conducting joint social activities and commemorative events and welfare assistance to currently serving members and work with the ex-Service co.

Every year, at about this time, Peter and his pals leave Brisbane and travel up to north Qld to be with SAS mates of theirs who are remote from the mainstream – just to bond and to let their mates know they are not forgotten.

Peter served in Vietnam from February 1969 to Feb 1970.

Towards the end of the afternoon, you could clearly see the stayers.

|

||

|

|

||

|

We find it very refreshing to see the number of females in high positions around the country. Have a look at the DVA organisation chart HERE where the majority of people in decision making positions are women. As well as those holding Directorships and/or Commissions, most of the section heads are also women. This holds true for other Government Departments too.

It’s great to see and it looks like the glass ceiling is a thing of the past.

Now, if only we can get rid of that Political Correctness rubbish.

|

||

|

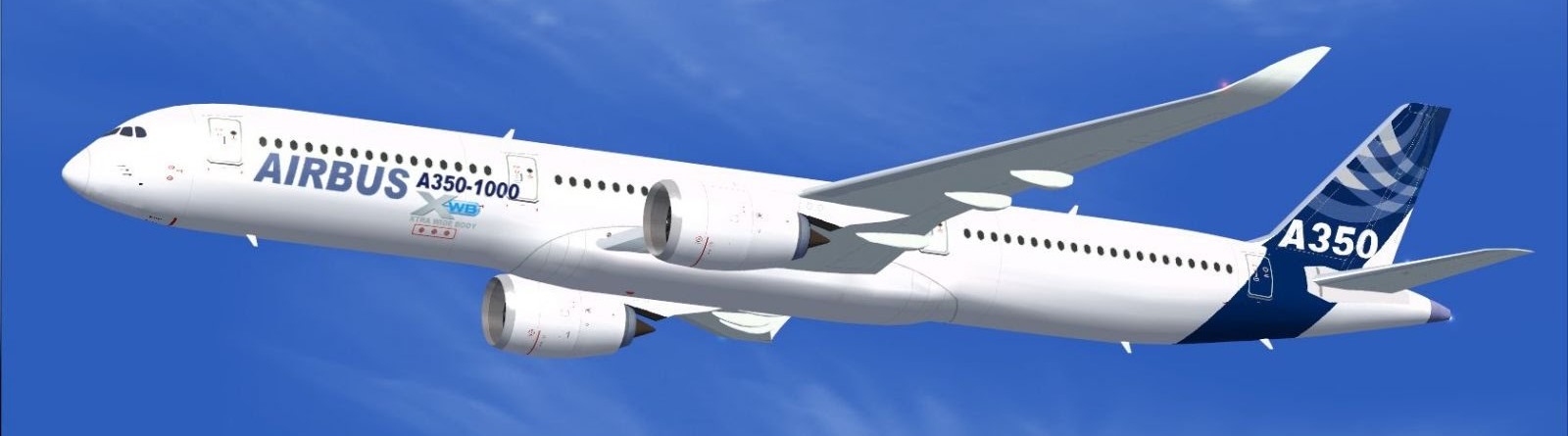

The newest version of Airbus’ A350 passenger jet completed a maiden flight recently during a well-attended event to see the long-haul market contender in action. The A350-1000, one of three test aircraft assembled at Airbus’ main facility in France, departed early Thursday before crowds of employees and potential customers, returning to Toulouse after a three-hour flight. The test models, the largest of the A350 series, will undergo about 1,600 hours of flight tests for certification. The standard 1000 version will have 366 passenger seats, a beefier version of the A350-900 that’s now in service and making it a contender against Boeing’s 777 series. Airbus contends that the composite-built A350-1000 will cost 25 percent less to operate than the B777-ER. The A350-1000 is slated to enter service in 2017.

Measuring nearly 74 metres from nose to tail, the A350-1000 is the longest-fuselage version of Airbus’ all-new family of wide-body jetliners, which is designed for high efficiency, maximum reliability and optimized performance.

In a typical three-class configuration, featuring Airbus’ 18-inch-wide economy class seats for modern comfort, the A350-1000 seats a total of 366 passengers. Combined with a range of 7,950 nautical miles, this represents a significant revenue-generating advantage for operators. The aircraft also can be configured for a higher-density layout to accommodate up to 440 passengers.

Meanwhile, Airbus, which also is undergoing a consolidation of its Toulouse operations to cut costs, faces potential roadblocks in completing deliveries of its current aircraft. Delays from suppliers have left incomplete A350-900 jets parked in Toulouse waiting for their cabins to be finished. Meanwhile, some smaller A320 jets waiting to be delivered don’t have engines from Pratt & Whitney – all of which indicates is a sign of suppliers struggling to keep up with demand for new components. But officials said the A350-900 is still on schedule for 50 deliveries this year despite ongoing concerns over suppliers. “It has improved, but it is not where it should be and we are watching them very carefully,” an Airbus official said. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

side was a knoll on which was perched the fortified Special Forces

camp, overlooking the river and hills to the west, and on the other

side the high valley wall to the east.

side was a knoll on which was perched the fortified Special Forces

camp, overlooking the river and hills to the west, and on the other

side the high valley wall to the east.

tight-fitting

Western dress, and her face overly made up. She spotted the

‘Australia’ caption on Dick’s cap. ‘Hi Aussie. How ’bout a beer, or

maybe “Saigon Tea”?’, she said suggestively. The latter, quoted at

750p (about US$7.50), seemed to involve more than a drink. ‘What

comes with the Saigon Tea?’ Dick wanted to know. ‘Short time with

me’, replied the girl with a wink. ‘How much all night?’ asked Dick.

‘Fifty dollar’, she said firmly. When Dick laughed, she said

impatiently, ‘What you want, Aussie?’ ‘Give us a “bar me bar”

replied Dick, grinning at me. The girl, realising she had been had,

laughed too, and went away to get our drinks. She came back with two

bottles and two grubby-looking glasses. We drank our ‘bar me bar’,

ignoring the sludge in the bottom of the bottle and the faint taste

of formalin, which left you with a horrendous gut-ache if you drank

too much. If you believed the rumour, ‘bar me bar’ was made from

Saigon River water and the formalin, more commonly used as an

embalming fluid, was added to kill the bugs!

tight-fitting

Western dress, and her face overly made up. She spotted the

‘Australia’ caption on Dick’s cap. ‘Hi Aussie. How ’bout a beer, or

maybe “Saigon Tea”?’, she said suggestively. The latter, quoted at

750p (about US$7.50), seemed to involve more than a drink. ‘What

comes with the Saigon Tea?’ Dick wanted to know. ‘Short time with

me’, replied the girl with a wink. ‘How much all night?’ asked Dick.

‘Fifty dollar’, she said firmly. When Dick laughed, she said

impatiently, ‘What you want, Aussie?’ ‘Give us a “bar me bar”

replied Dick, grinning at me. The girl, realising she had been had,

laughed too, and went away to get our drinks. She came back with two

bottles and two grubby-looking glasses. We drank our ‘bar me bar’,

ignoring the sludge in the bottom of the bottle and the faint taste

of formalin, which left you with a horrendous gut-ache if you drank

too much. If you believed the rumour, ‘bar me bar’ was made from

Saigon River water and the formalin, more commonly used as an

embalming fluid, was added to kill the bugs!

Trang. Both were deserted. Bus and train services had been virtually

abandoned after frequent ambushes and atrocities. In my 12 months in

Vietnam, I saw only one functioning train, even though there were

hundreds of miles of railway track. Only peasant farmers dared to

travel unprotected on the roads, their bullock wagons no doubt

testifying to their innocent objectives. Military convoys, of

course, were always well protected.

Trang. Both were deserted. Bus and train services had been virtually

abandoned after frequent ambushes and atrocities. In my 12 months in

Vietnam, I saw only one functioning train, even though there were

hundreds of miles of railway track. Only peasant farmers dared to

travel unprotected on the roads, their bullock wagons no doubt

testifying to their innocent objectives. Military convoys, of

course, were always well protected.  put its hoof down the gap between cage and cargo ramp. Its bovine

expression changed to stubbornness. The Vietnamese shrugged

helplessly. But the cow reckoned without Bugs Rose. Aiming a swift

kick at its rump, he jumped into the aircraft, bellowing like a fan

at a football final as he hauled on the cow’s tethering rope. The

Vietnamese beamed in admiration as the reluctant animal trotted

forward. And so I set off for Van Canh with my first ‘veg and

livestock’ cargo, a mixture of boxed cabbages, crated geese and the

recalcitrant cow tethered to the sidewall of the cargo compartment.

The Wallaby smelt more like a farmyard than an aeroplane.

put its hoof down the gap between cage and cargo ramp. Its bovine

expression changed to stubbornness. The Vietnamese shrugged

helplessly. But the cow reckoned without Bugs Rose. Aiming a swift

kick at its rump, he jumped into the aircraft, bellowing like a fan

at a football final as he hauled on the cow’s tethering rope. The

Vietnamese beamed in admiration as the reluctant animal trotted

forward. And so I set off for Van Canh with my first ‘veg and

livestock’ cargo, a mixture of boxed cabbages, crated geese and the

recalcitrant cow tethered to the sidewall of the cargo compartment.

The Wallaby smelt more like a farmyard than an aeroplane.  ould

see here were tents, mud and Montagnards. Some of the advisers here

were on their second or third tours, and were decidedly weird. After

exchanging pleasantries, they lapsed into a world of their own.

Living in this muddy, makeshift camp, miles from anywhere in a

foreign country, training unsophisticated mountain tribesmen in the

art of counterinsurgency warfare, who would blame them? Only one man

seemed cheerful and well adjusted. He was a huge black man with

reddish hair and Asian eyes who told us he had ‘married’ a

Montagnard woman. He asked all sorts of questions about ‘Orstralia’,

the Davis Cup, and ‘those little Cola bears’.

ould

see here were tents, mud and Montagnards. Some of the advisers here

were on their second or third tours, and were decidedly weird. After

exchanging pleasantries, they lapsed into a world of their own.

Living in this muddy, makeshift camp, miles from anywhere in a

foreign country, training unsophisticated mountain tribesmen in the

art of counterinsurgency warfare, who would blame them? Only one man

seemed cheerful and well adjusted. He was a huge black man with

reddish hair and Asian eyes who told us he had ‘married’ a

Montagnard woman. He asked all sorts of questions about ‘Orstralia’,

the Davis Cup, and ‘those little Cola bears’.