|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

My Story.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Angus Meikle

This story is not one of derring-do although as one of many who earned

the right to wear the 1939-45 Star as well as the France and Germany

Star, I had my moments. Having reached the time of life at which the

award of the OBE (Over Bloody Eighty) is due, I have long since learned

not to dwell on past sadness in wartime memory. So what

During World War II there were four types of service - Air Force, Navy, AIF and Citizen Military Force (CMF). If you were under twenty-one, you had to have your parents’ permission to join the first three mentioned as these automatically included overseas service. On the other hand all males eighteen or over but not in the first three services were called-up in the CMF if not in a ‘Reserved Occupation’. My mother would not consent to my joining the Air Force so in to the Army I went. When riding a Harley Davidson from Townsville to Charters Towers, I had an accident which resulted in my being medically classified as Army “B” Class and I found myself manning the telephone switchboard in Townsville. One day, an Air Force Recruiting Unit arrived in Townsville and I asked my C.O. if he would release me if I could join the RAAF as Aircrew. To cut a long story short, the RAAF gave me a medical examination which I passed as they were not worried about a damaged leg. So it was back to Brisbane and my first RAAF posting to No. 3 Initial Training School (ITS) at Kingaroy.

At the outset we were told that the top six out of a course of thirty-two would in all probability be categorised as pilots. I made up my mind to be one of them. Like most other pilots of the day, my flying started on the Tiger Moth, a well-known biplane which is still flying. My training took place at No 5 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Narromine in western New South Wales. First built in 1934, the Tiger Moth is arguably the safest aircraft ever built, but one of the most difficult to fly well. It has a wooden frame covered with fabric. A joy stick which controls the ailerons and elevator is extremely sensitive. On the other hand, if the motor packs up, the plane is like a glider. Despite its frail appearance it is fully aerobatic. I hope readers have an opportunity to fly in a Tiger Moth, it is a wonderful experience.

After my initial pilot training, I was posted to No. 8 Service Flying

Training School (SFTS) at Bundaberg, Queensland flying twin engined Avro

Ansons. The old Anson had a metal frame which was fabric covered

although the wings were all metal. It was a wonderful aircraft to fly as

it had no vices or bad habits. The aeroplane had a retractable

undercarriage which had to be wound up and down by hand. The winding

handle was located on the right-hand side

Graduating from Bundaberg as a Sergeant Pilot I was posted to No.1 Air Observer School (AOS) as a staff pilot training navigators. After six months, I boarded the ‘Mariposa’ in Sydney for a non-stop run of 16 days to San Francisco. There were only a few Australian airmen on board the ‘Mariposa’, but there were millions of lice. The ship was on its way back to America for a refit after bringing several thousand Italian prisoners-of-war from the Middle East to Australia. We stayed in San Francisco for about ten days followed by a wonderful train trip to New York. From there, it took us four days to cross the Atlantic Ocean in the ‘Queen Mary’. There were four thousand on board and the kitchen staff took all day providing us with two meals a day.

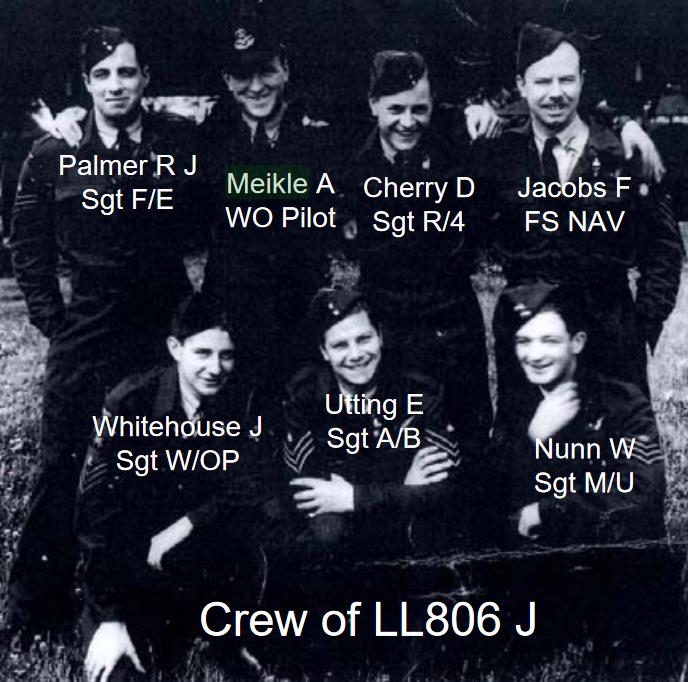

Arriving in UK I had a short stay at the Grand Hotel holding camp Brighton then I was posted to No. 20 Advanced Flying Unit (AFU) for a refresher course flying Airspeed Oxfords. That was followed by a posting to No. 11 Operational Training Unit (OTU) situated next to Maryborough Castle just outside Oxford. The unit was equipped with Vickers Wellingtons - more about them later. Our first task was to ‘crew up’. Something like twenty of each Pilots, Navigators, Wireless Operators, Bomb Aimers and Air Gunners all arrived at the station around the same time. Being an RAF outfit, there were only two Australians there (both pilots) all the rest being English. For the first two weeks we all mingled and at the end of that period the pilots, by mutual agreement were expected to have selected their crew. Our crew consisted of myself Pilot, Flt Sgt Fred Jacobs - Navigator; Sgt Jim Whitehouse - Wireless Operator; Sgt John Utting - Bomb Aimer; and Sgt Don Cherry - Rear Gunner.

So the time came to fly the beast. The Wellington was both a unique and

a shocking aircraft to fly. It was underpowered with 2 x 850 horsepower

Pegasus engines and it glided like a brick. I vividly remember one night

when I bounced it on the runway so hard that, when at the top of the

rebound, I could not see the runway lights. So with full power on and

throttles wide open, the Bomb Aimer sitting in the co-pilot’s seat and

the Wireless Operator standing between us looking out into blackness, we

flew over the countryside at about 100 feet at approximately 120

The unique aspect of the Wellington was that it was the only aircraft built by geodesic construction. The fuselage was constructed of round aluminium tubes criss-crossed all the way along. This frame was then covered with fabric. The Wellington was designed and built before the war and was used for many purposes other than bombing raids on Germany. For example it was used by Coastal Command on anti-submarine patrols and in the Middle East for long-distance courier services. I can truthfully say that I never once landed a Wellington correctly. After leaving Wellingtons behind, we next went to a Heavy Conversion Unit to learn to fly Lancasters.

From one extreme to the other! As soon as I flew a Lancaster we were as one. It handled superbly, had no vices and was easy to fly. It had power to spare. In fact, at about 5000 feet and fully laden, it could maintain height on any two engines. It was, without doubt, the finest heavy bomber used during World War II. It was powered by 4 x 1500 hp Rolls Royce Merlin engines and could climb to 21000 feet. Our crew was the same except that we added two more members, Sgt John Palmer - Flight Engineer and Sgt Bill Nunn - Mid-upper Gunner. So now we had a total crew of seven.

Up to this time we had all been NCOs and at 21 years of age, Fred and I were the old men of the crew. All the others were 18 and 19. At the end of our conversion training, we were posted to No. 15 (RAF) Squadron to fly Lancasters on operations. As was the custom upon arriving at a new unit, the Pilot reported to the Commanding Officer. As soon as I walked into his office his first comment was “Meikle, why aren’t you a commissioned officer”? My reply was that I didn’t know. “Well” he said “As of now you are a Pilot Officer”. When I was leaving his office an hour later he added “You are now a Flying Officer so you must take this memo to the Adjutant”. This was the first time our crew had been split up in living conditions.

No.15 Squadron celebrated its 75th birthday in 1990, having

been formed in 1915. It is the oldest RAF Squadron still operational.

The stone buildings at Mildenhall are magnificent and when I was there

the station also housed Headquarters of No. 3 Group with an Air

Commodore as Commanding Officer. The administrative style was

traditionally RAF to the point that even in wartime we had to ‘dress’

for dinner in the Officers’ Mess and we were paid

Now to actual operations. Firstly, let me say that every time we headed down the runway with a fully laden ‘bombed-up’ aircraft I was terrified. Most of the time the weather conditions were shocking, flying through cloud and storms on most sorties. We had no modern navigation or radio aids so all navigation was done on a ‘dead-reckoning’ plot with the possibility of a position fix being made by the Navigator using a bubble sextant during a break in the cloud or by the Wireless Operator using a loop aerial. With a bit of luck the Pilot may catch a glimpse of the North Polar star. About an hour before take-off the Pilot and Navigator attended a briefing conducted by the C.O., giving us details of target, heights, speed, tracks, fuel load and the like. We then worked out our course, having been provided with the known or estimated wind speed and direction. The Pilot made a small copy for his own use as a back-up in case anything happened to the Navigator. Then out to the aircraft.

If it was covered with ice or snow, you would wait for the glycol tanker to arrive to spray the aeroplane. Then it was away as soon as possible. On our return, the aerodrome could be covered in cloud from 0 to 20 000 feet. We were fortunate at Mildenhall in that we had ‘Fido’ which was a fog dispersal device. Fido consisted of pipes running down the side of the runway with burners, similar to blow torches, at regular intervals. When lit and in full operation, the fog/cloud base was raised to about 500 feet, sufficient to permit a visual landing. I remember one night when our airfield was completely fogged-in, an aircraft called up on radio requesting Fido be lit as he was running out of fuel and could not return to base. That particular request was unusual because the aircraft was a massive Sunderland Flying Boat which, of course, did not have wheels. The pilot was instructed to land on the grass which he did impeccably with hardly a dent in the aeroplane. Naturally, it had to be taken to pieces for removal.

I mentioned before that all flight times and courses were calculated at the briefing before take-off. There was one unforgettable occasion when the information was very much in error. We were heading for Kiel, with a forecast wind of something like 60 knots from the south-west. A few minutes before we were to turn south at Point X onto the final leg to the target, we saw in front of us a city all lit up. It could only be a major city in neutral Sweden, a long way past our turning point. We calculated that instead of experiencing the predicted wind effect the actual wind was westerly at 120 knots. I immediately descended to a lower altitude to get away from the high level wind effect, otherwise we would not have sufficient fuel to get home against such a strong wind. On the way home we found and bombed Kiel, then descended to sea-level, cutting out the planned northern triangle and flying straight home on dead-reckoning navigation, having no radio beacon to guide us.

The average duration of those operations was approximately five hours

during which time the pilot and rear gunner were strapped to their seats

with their parachutes acting as seat cushions. The remainder of the crew

could move about as they each wore only a parachute harness. Their

clip-on ‘chutes were stored in a readily accessible rack. Only once were

we hit by anti-aircraft fire, losing our starboard engine. Another

occasion which initially scared the pants off us was the first time we

carried a mid-under gunner. When he opened fire the noise inside the

aircraft was horrific and everybody’s blood pressure went through the

roof. The introduction of mid-under gunners in selected aircraft came

into being after the Air Force had suffered many casualties as aircraft

were coming in to land at home

Just being part of a bomber stream at night carried its own risks. External lights attracted night fighters so we operated in darkness. Our only signal that we were too close to one of our own was when one of the crew reported seeing a red hot exhaust. After ‘D-Day’ we began to operate in different fashion. No.3 Group was put on a crash course of daylight formation flying - the only Group in the RAF to do so. The aim, with fighter cover, was to bomb bridges and like targets in support of our advancing Armies. Formation flying in fast manoeuvrable aircraft was very different to formation flying in slower heavily laden Lancasters. The worst experience in that type of operation was when an aircraft ahead was blown up and you had to continue in formation through where he had been. During the closing stages of the war, the Germans opened the dykes and flooded Holland with sea water. The whole Dutch population was confined to the major cities on high ground. In a life-saving operation, Bomber Command sent in over a thousand aircraft daily, each carrying 15 000 pounds (6 800 kg) to Holland. The food, including flour, sugar 5 and tinned commodities, was packed in jute sugar bags and stacked in the bomb bay. We dropped our loads on race courses and on playing fields at exactly 500 feet in height at a speed of exactly 150 knots. It was a very exciting and satisfying exercise from a pilot’s point of view to fly a four-engined aircraft at low level.

The reason for the precision flying was that at the point of impact the bag would have lost its forward momentum and did not have time to gather great downward speed. The plan worked and the bags did not break. Within an hour there was quite a mountain of food at any one drop zone and crowds of people would be waving and cheering. From our point of view it was a great humanitarian experience.

Toward the end of hostilities, some Lancasters were modified by removing the bomb doors to carry a 20 000 pound armour-piercing bomb (they were known as ‘Ten Ton Tessies’) across the Channel to the submarine pens in France. The Lancaster was an extremely strong aircraft yet at the same time, very responsive. You could fling it from one wing tip to the other in a matter of seconds, but you needed to warn your crew first! The Lanc was capable of diving at a speed in excess of 500 m.p.h. and I believe that there were recorded instances when the aircraft survived rolling through 360 degrees during storms. There are also stories about individual Lancasters - the hardware in which we flew. For example our No. 15 Squadron aeroplane, Lima Sierra Juliet in today’s phonetic alphabetic parlance, was ‘The Greatest Survivor’ of World War II Lancasters, carrying its crews through 142 operational missions.

Immediately after the war we were sent to all parts of Europe to fly

back prisoners-of-war. We would land at a variety of aerodromes, most of

which were well spotted with bomb craters. Something like 200 Lancasters

would line up one behind the other and wait for trucks to bring in POWs.

Usually we loaded each aircraft with 25 passengers. I still do not know

how they were fitted in. It was not all flying and no play. In fact we

enjoyed quite liberal leave and I was fortunate enough to see a great

deal of the UK including Cornwall and Scotland and most parts in

between. I got to know my father’s family and I spent a lot of time with

them and with families of my crew. It is worth mentioning here

With the drastic food rationing in the UK we were naturally welcomed with open arms. One night I will always remember was the celebration of VE Day - the end of the war in Europe. I was in a little town called Kilmarnock. Everybody was dancing in the main street, the whisky was flowing and the kilts swirling, but I was not allowed to dance as I was in uniform and not in a kilt. Someone loaned me a kilt which I wore over my uniform trousers and a great night was had by all. During some of my leave in London I visited all the famous landmarks. On those occasions, I was introduced to live theatre, ballet and orchestral music which I immediately loved. Let me say also that I met some delightful English girls and enjoyed their company but I did not get involved in any serious attachments for two good reasons. Firstly, none of us knew when our number could be up and secondly, I could never live in a cold climate.

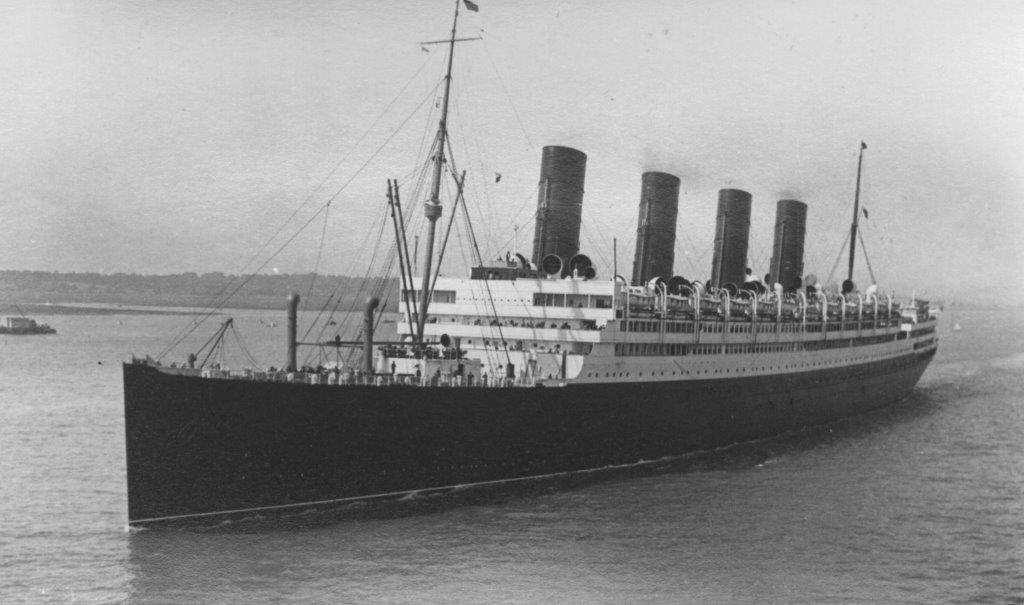

In any case, all I ever wanted to do was to return to Australia in one

piece. That return was on the old ‘Aquitania’ which was similar to the

ill-fated ‘Titanic’. So the war period of my life came to an end. I

joined on 10th February 1942 and was discharged on 18th

January 1946. I loved the exhilaration of flying. In fact, I still do.

In retrospect, I look at that segment of my life as a memorable

experience of which I concentrate on the positive, pleasurable aspe

My crew and I corresponded ever since WWII. The close relationship between us and the raw emotions we shared, I might say, could not occur in peace time. Due to the passage of time, Don Cherry my former Rear Gunner is the only surviving crew member apart from myself. He lives near Seville, Spain. Shirley and I visited him during our trip to Europe.

As a postscript, I would like to add that former ACA Branch President and current Archivist Eric Cathcart was a fellow member of my flying training courses at Kingaroy, Narromine and Bundaberg where we both graduated as pilots. Until we came together seven years ago in our ACA Branch, we had not seen each other since 1943. Neither of us has changed one iota !!

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

F-111C Aircrew Reunion Annual Dinner.

The F-111C Aircrew Association was formed on the 3rd December 2010, the

same day the RAAF retired the

The aim of the Association is to provide a structure where all those who flew in the mighty Pig in RAAF service can get together, even if only in cyberspace and hold an annual dinner to keep the spirit alive by telling some old and very bold stories - as well as downing the odd one or two as it was ever thus. Retirement being the great equaliser that it is, all members are equal in the Association and anything done since a member’s time on the “Pig” is of passing interest only.

Old wounds are banned, Left or right hand seat doesn’t matter and there is no retained rank, everyone’s hours are equal in quality and everyone’s stories are worth listening to – more hours in the log book means nothing more than the member should have more stories to tell.

The RAAF purchased the F-111 from General Dynamics in 1963, but because of many setbacks the first aircraft was not accepted until 1973, some years after many of those who had gone to the US to learn the aircraft had in fact left the RAAF. Once here though, it proved to be an extremely capable aircraft and those that flew in it and those who worked on it - loved it.

This year’s reunion was the seventh to be held since the Association inauguration and was once again held at the United Service Club in Brisbane.

|

||

|

|

||

|

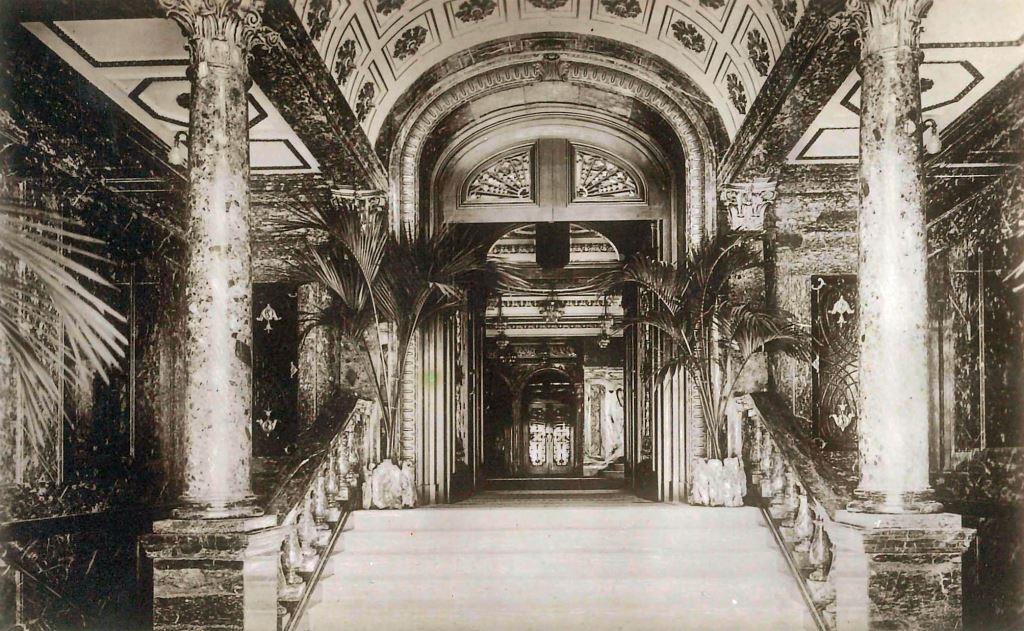

The United Service Club is situated at 183 Wickham Terrace, in Spring Hill, and overlooks the city of Brisbane. It was formed back in 1892 and opened by Major General John Owen, the Commandant of the Queensland Defence Force.

Towards the latter part of the nineteenth century, in the Colony of

Queensland, the Brisbane based officers of the Defence Forces used to

gather in rowdy taverns, one of the first meeting places was the

Shakespeare (later renamed Cecil) Hotel in George Street, long since

gone. For some time the idea of forming an officers' club with its own

premises had been favoured and talked about, but the drive and

initiative needed to bring it about seemed to be lacking, at least until

Major General John Fletcher Owen arrived from England in 1891 to take

over as Commandant

Then in about 1900, the Club was given the two story building “Aubigny”

which was situated at 293 North Quay

In 1914 the Club purchased a block of land at 70 George St and plans were submitted to build a single storeyed brick building to be its new club house (also long gone, now the new Gov’t Executive Building). The Club (below) stayed there for the next 33 years. This was an era when a drink (or 6) after work was considered to be a wise precaution before facing the rigours of the homeward journey, by tram or steam train and, of course, there was no more agreeable place for a man to honour this custom than at his club. Therefore it became a regular meeting place for many members around 5 pm. |

||

|

After several years, it was obvious that the single story building was inadequate for the Clubs’ needs and a second story was added. It is believed that 1929 was the year in which the Club acquired one of its most treasured trophies, the navigation lights from the cruiser HMAS Sydney, famous for vanquishing the German raider Emden at Cocos Island in 1914. They are now mounted on the port and starboard sides of the front door of the present building and add distinction to the Club entrance.

In 1935, at the annual general meeting, a proposal was put forward that the Club be converted into a residential Club with particular regard to reciprocity with other Clubs. In 1936 the committee started to look around for alternate premises which would include accommodation facilities.

As in all gentlemen’s clubs at that time, generally, ladies were invited only on very special social occasions, such as dances. So when the Club’s tenant, the Naval and Military Institute, sought permission to invite ladies to a lecture on the Great Barrier Reef there was a reluctance in the committee’s granting of this request, subject to the proviso that it was ‘not to be taken as a precedent’. In the event, the “privilege” was abused to the extent that some ladies were observed in the lounge. Expressions of displeasure were conveyed to the Institute.

Also, for many years previous to 1937, there had been poker machines in

the bar but the profit from them had never been mentioned as a separate

item which leads to the presumption that their legality was in question.

The decision at the last committee meeting for the year that 'pending

new legislation to be passed, the poker machines be removed from the

bar, and stored for future action' suggests that a new law to put their

illegality beyond doubt was imminent. The following year, after the

committee had taken legal advice, they were placed in storage and never

used again.

In September 1939, the Club went into war mode. Negotiations which were underway to purchase the building next door were shelved and a proposed squash court was cancelled. Experience gained from WW1 seemed to be behind the decision to stock up with 200 gallons (750 litres) of scotch whisky – just in case the conflict went beyond the predicted six months. This quantity was increased in May 1940 when things looked more dire than originally thought and the tally was increased to 370 gallons (1,400 litres). Whisky drinkers had an alternative to scotch in an Australian brand of firewater named Corio whisky, after the locality in Victoria where it was distilled; a perfectly wholesome drink lacking only palatability. As the war dragged on customers were obliged to accept an increasing proportion of this local product in their whisky orders, and some drinkers even developed a liking for it which lasted after the war; but only until scotch became freely available once more.

The war had wrecked havoc with the Club’s clientele with most overseas fighting and things looked bleak - until the 7th December – Pearl Harbour. By the 22nd December, some American personnel had already arrived in Brisbane and the Committee resolved to send letters to all the American Units inviting them to become honorary members of the Club. The influx of allied service officers boosted the Club’s treasury considerably.

When peace broke out in 1945, the Club was poised to rise to new heights as a first-rate Club, exclusive as always to gentlemen holding a King's commission in either the Navy, the Army or the Air Force. There were hundreds of eligible officers eagerly seeking admission to a place where old comrades in arms could meet in congenial surroundings to partake of a drink and a meal in each other's company and, perhaps, refight a battle or make plans for some future contest on a sporting field. The problem was how to enlarge the circle to accommodate all those newly demobilised young officers waiting to come in. Clearly the only answer was to acquire new premises adequate to the needs; a well situated building providing ample space, comfort, overnight accommodation and having a dignity befitting the status of the Club.

Then in July 1946, one of the Club’s members, a Major Maldwyn Davies mentioned that his family owned a property in Wickham Terrace called Montpelier and which the family wanted to sell. The property was valued at £30,000 ($60,000). As a building, ‘Montpelier’ had a fascinating background. William Davies, Major Davies’ father, had made his fortune in Gympie during the gold mining years. He bought the site in 1897, on which stood an old timber lodging house, no doubt at an excellent price for the colony was then gripped by a severe depression and real estate values were extremely low. Then, in 1907, William Davies demolished the old house and erected a new brick structure of three stories, using first grade materials and good craftsmen. The contract price was £7000 and the building was designed specifically as a private hotel providing short and long term accommodation for gentlemen and their ladies. As a private hotel, ‘Montpelier’ had the highest standards for clientele, even decades later; the late Roderick S Colquhoun, the first Queensland manager for The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited, stayed at ‘Montpelier’ for a few weeks in 1938 while looking for a permanent residence. Colquhoun later recalled that his reservation was not accepted until he had arranged a recommendation from a well-known businessman. During the war, it was requisitioned by the US forces as accommodation for officers of Field rank.

In September 1946, the Club’s Committee decided to proceed with the purchase of the current building for the sum of £30,000 and also authorised a further £20,000 to be spent on alterations and furnishings. It was also decided to buy the timer building, known as the Green House (below), which was built in 1907 and is situated to the east of Montpelier. 26th May 1947 was the date set for the opening of the new bar. Membership had by then grown to 2168 persons.

The Green House from the street.

Green House from the Club's car park.

Immediately following the Club’s acquisition of the site, conversion

teams of carpenters, bricklayers, electricians, refrigeration experts

and others began to refurbish the two buildings. The ground floor of

Montpelier was “converted” to two lounges, a dining room, library, and

kitchen, the second floor to residential rooms and the third floor for

(In our opinion there is nothing so boring as an all male event – tb)

By the middle of 1972 Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War had virtually ended. The last infantry battalions had returned home earlier in the year; logistics troops were packing up and leaving; in Australia the numbers of young men being conscripted were reduced and their term had been shortened from two years to 18 months; public support for the war was almost non - existent; everywhere, the military seemed to be on the defensive. In the media, in the schools and universities, even in the public service, there were strong feelings against the war in Vietnam and against all matters military. Forced to bear the brunt of an unpopular war, the military seemed to retreat into a shell. This anti-war, anti-Vietnam veteran feeling permeated many aspects of society, even going so far as to affect the United Service Club

Unlike WW2, Vietnam did not produce a sudden rush of veterans who joined the club as members consequently the Club’s Committee had to wrestle with the important issue of declining patronage.

Club Entrance.

It was about this time that Westfield and Civil and Civic came acalling, indicating they were both interested in buying the property but these offers were short lived and evaporated before any recommendations could be put to the committee. It was decided to stay put for the next 5 years and see what happens.

This proved a wise decision. In December 1972 the first Labor Government

to hold office since 1949 led to huge increases in inflation. The club’s

trading position suffered severely, not just from the changed economic

and political

In 1974, under the pressure of reduced usage and difficult trading, the controversial question of civilian membership was finally faced by the Committee. In its history, the Club had always prided itself on its military origins and on the military service of its members. In all its premises, it had much of the atmosphere of an Officers’ mess or wardroom; the same, easy, gentle rules prevailed; the same polite but not obsequious deference to rank, the same feeling of belonging to an organisation with a common purpose and being with fellows of a common background. Yet by the late 1960s the proportion of the population that were potential members - those with commissioned service in one of the armed forces - was declining. The future of the Club was at risk. By the early 1970s, however, it became apparent that, were the Club to survive, it would have to open its books to members who might not have had the required service background. Now it was possible that the entire nature of the Club might change with the influx of civilian members. Many thought the Club had passed its heyday.

However, membership of the United Service Club had distinct advantages for the many professional men and women with their offices or surgeries in the area. The medical profession, with its close links to the armed services, was a clear source of potential members. So were the professions of architecture and engineering, as many firms had moved into offices in Spring Hill where the rents were less steep than in the central business district. Accountants, lawyers and business consultants, often faced with long waiting lists to the other city clubs such as the Brisbane Club and Tattersall’s, found advantages in seeking membership of the United Service Club. Indeed, during the 1970s, the area between Wickham Terrace and Gregory Terrace started to be transformed with both residential and office developments. Each new professional office that moved into the area provided some potential members for the Club.

Club Dining Area.

The Club's billiards room.

The Members' Bar - on a quieter day.

The Military Bar.

But among some of the more traditional members, those who clung rigidly

to the idea that the United Service Club

A passageway was built connecting Montpelier with the Green House - which is now used as a dining area downstairs and accommodation upstairs.

There was no doubt that the membership was aging rapidly and it became apparent that an examination of the possibilities of broadening membership was indeed necessary. The imperatives were no longer those of the preserving the character of the Club – rather the preservation of the Club itself.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Montpelier, the main Club building with the Green House on the right.

|

||

|

In July 1974 members of the Club voted overwhelmingly (more than 84%) in favour of introducing civilian membership. That year saw an improved patronage of the Top Bar, which an earlier Committee had thought about closing.

In 1978 Montpelier was certainly showing its age and over the next few years considerable redecorating and installation of better equipment was carried out in the bars, dining rooms and accommodation area but the Club moved slowly into the computer age. In October 1984 legislative changes by the Federal Government in the area of sexual discrimination meant that the Club had to examine closely its membership rules. This meant that both males and females would be eligible to be elected to service or civilian membership in accordance with their appropriate category. Changes were in the wind.

On the 18th August, 1988 more than 70 members and friends attended the Club’s first Vietnam Veterans Day luncheon. That Vietnam Veterans Day luncheon was the first of what has become an annual and successful occasion.

The Club was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on the 28 April 2000. If interested, you can read the history of the Club, which includes some background information on early Brisbane, HERE.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

It was in this wonderful old building with its tons of old world charm, it abundance of stained glass windows and beautiful paintings that the F-111C Aircrew Association Committee had decided to hold their annual get togethers.

You can click each of these photos which will give you the HD version which can be downloaded or printed.

|

||

|

|

||

|

“Rocky” Logan, Dave Millar.

|

||

|

David Clarkson, Al Blyth, Peter Growder.

|

||

|

Keith Oliver, John McCauley, Alan Curr, Steve "Johnny Wog" Perret.

|

||

|

Greg Choma, Omar Rafei, Geoff Shepperd.

|

||

|

John Bennett, Greg “Fitz” Fitzgerald, Mike “Boggy” Smith, Rick “ROF” O'Ferrall. |

||

|

|

||

|

John Tyrell, Barry Sullivan, Tony Stankevicius.

|

||

|

Kevin Paule, Peter Layton.

|

||

|

Lindsay Boyd, Bob Bruce, Dave Rogers.

|

||

|

Mark Streat, Geoff Ross, Peter Lloyd.

|

||

|

Mike Maddox, Dave Dunlop, Alan Curr.

|

||

|

Mike Smith, Mike Maddocks, “Rocky” Logan.

|

||

|

Steve Williams, Glen Ferguson, Shannon Hudson, Zalie Duffy, Adam Lovatt.

|

||

|

Stuart Cooper, Rob Montgomery.

Soon it was time to move into the dining room.

|

||

|

Michael Smith, Kevin Paule – with the mighty Pig centre stage.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Some interesting videos. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

of the pilot’s seat and it took something like three hundred turns to

retract the undercarriage. So you can imagine what it was like doing

solo circuits and bumps. It was such a safe aeroplane that after the

war, fitted with an hydraulic undercarriage, it was used as a civilian

passenger aircraft.

of the pilot’s seat and it took something like three hundred turns to

retract the undercarriage. So you can imagine what it was like doing

solo circuits and bumps. It was such a safe aeroplane that after the

war, fitted with an hydraulic undercarriage, it was used as a civilian

passenger aircraft. knots (220 k/ph). The problem was that we did not have enough height to

raise the flaps with safety. However, after missing several church

steeples we returned to base some twenty minutes later, relieved but

with very rapid heart rates.

knots (220 k/ph). The problem was that we did not have enough height to

raise the flaps with safety. However, after missing several church

steeples we returned to base some twenty minutes later, relieved but

with very rapid heart rates.  an extra two shillings and sixpence per day because we did not have a

batman. Each bedroom had its own fireplace and that was absolute heaven

after spending my previous time on wartime aerodromes sleeping in Nissan

huts. One particularly good point about Air Force conditions was that if

you came back from an operational sortie, you came back to a degree of

comfort.

an extra two shillings and sixpence per day because we did not have a

batman. Each bedroom had its own fireplace and that was absolute heaven

after spending my previous time on wartime aerodromes sleeping in Nissan

huts. One particularly good point about Air Force conditions was that if

you came back from an operational sortie, you came back to a degree of

comfort.  base with wheels and flaps down. The German Air Force had modified a

number of twin-engined night fighters with upward-firing cannons and

they were very effective against ‘sitting duck’ targets.

base with wheels and flaps down. The German Air Force had modified a

number of twin-engined night fighters with upward-firing cannons and

they were very effective against ‘sitting duck’ targets.  that the RAAF had taken over the Strand Palace Hotel as an Australian

leave hostel in London. Australia House is adjacent and if you were

going to spend leave with a family, you could call at Australia House

and collect half a kit bag of Australian produce such as tinned butter,

fruit and meat as a gift to your host.

that the RAAF had taken over the Strand Palace Hotel as an Australian

leave hostel in London. Australia House is adjacent and if you were

going to spend leave with a family, you could call at Australia House

and collect half a kit bag of Australian produce such as tinned butter,

fruit and meat as a gift to your host.  cts.

Several years ago, in company with my wife Shirley, I visited Mildenhall

on a nostalgia trip organised by my late Bomb Aimer’s brother, Patrick

Young. R.A F. Mildenhall is now an American base for Airborne Refuellers.

The Commander of the base, U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Lyle, gave us

the red carpet treatment for a full day. One which will live long in our

memories.

cts.

Several years ago, in company with my wife Shirley, I visited Mildenhall

on a nostalgia trip organised by my late Bomb Aimer’s brother, Patrick

Young. R.A F. Mildenhall is now an American base for Airborne Refuellers.

The Commander of the base, U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Lyle, gave us

the red carpet treatment for a full day. One which will live long in our

memories.

3

billiard rooms, card room and bathing facilities. All levels originally

had wide verandas facing the city but these were closed in on the 2nd

and 3rd floor sometime later. The Green House was not

utilised by the Club at this time but was rented to an exclusive ladies

Club. Although the Club was a very early pioneer in having ladies as

members, its members in 1960 still retained an old-fashioned, perhaps

even chauvinistic, attitude towards ladies. At a committee meeting in

January, 1960, the president, Wing Commander Christensen, expressed his

disapproval at the fact that ladies had been entertained at a function

held by the Royal Flying Doctor Service. This, the president said, was

not an 'authorised' ladies’ night; the minutes record that 'the

secretary was instructed to convey to the member responsible an

expression of the committee's disapproval. However, soon afterwards the

committee experimented with a mixed dining night, this time for members

connected with the Mater Hospital. The first cracks had begun to appear

in the facade of masculine domination.

3

billiard rooms, card room and bathing facilities. All levels originally

had wide verandas facing the city but these were closed in on the 2nd

and 3rd floor sometime later. The Green House was not

utilised by the Club at this time but was rented to an exclusive ladies

Club. Although the Club was a very early pioneer in having ladies as

members, its members in 1960 still retained an old-fashioned, perhaps

even chauvinistic, attitude towards ladies. At a committee meeting in

January, 1960, the president, Wing Commander Christensen, expressed his

disapproval at the fact that ladies had been entertained at a function

held by the Royal Flying Doctor Service. This, the president said, was

not an 'authorised' ladies’ night; the minutes record that 'the

secretary was instructed to convey to the member responsible an

expression of the committee's disapproval. However, soon afterwards the

committee experimented with a mixed dining night, this time for members

connected with the Mater Hospital. The first cracks had begun to appear

in the facade of masculine domination.  climate but from the differing attitude towards drinking in the

community. In 1973, with profits dwindling, the decision was taken to

allow ladies into the dining room at lunchtime.

climate but from the differing attitude towards drinking in the

community. In 1973, with profits dwindling, the decision was taken to

allow ladies into the dining room at lunchtime.