|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

Some of the photos on this page have been crunched to allow the page to open quicker. You can click those pics to get the HD version which look better.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Watsons Bay, NSW.

Recently I had the good fortune to spend the better part of a week in the Harbour-side Sydney suburb of Watsons Bay. For those days I was forced to endure the vista below but by adopting a stoic approach I was able to endure it without suffering too much pain.

|

||

|

As well as being one of the most beautiful suburbs in Australia, Watsons Bay has a very special place in our nation's history. The first European landfall in Sydney Harbour occurred in Watsons Bay on the 21st January 1788, when Captain Phillip and his party came ashore at South Head and camped overnight at Camp Cove (below) on their way to select the site for what is now Sydney. Camp Cove had a freshwater spring behind the beach so proved a suitable place for a night’s camp.

|

||

|

|

||

|

South Head was a site of return visits by the officers of the First Fleet, as it marked not only the entrance to the Harbour but the most accessible site from which they could observe the ocean and coast down to Botany Bay. In January 1790, a Captain Hunter and others from the HMS Sirius, the flagship of the First Fleet, went to South Head to erect a flagstaff which would serve as a landmark for ships arriving at the heads, as well as serving as a means of communicating their arrival to the new settlement at Sydney Cove. A signal station (below) took over the job in 1838 of notifying the city and local pilots of the arrival of ships. Watsons Bay was named after Robert Watson who was employed as a Signal Master.

|

||

|

|

||

|

For the Colony’s first 50 years, the signal station was a basic lookout hut, a flagpole and a signal staff for semaphore flag signals. A new signal house was built in 1841 and was added to over the years until the station went out of official use in 1992.

To the south of the signal station stands Macquarie Lighthouse, which was built in 1816 and later replaced by a near identical building. After the famous 1857 wrecking of the Dunbar on the rocks below The Gap and 9 weeks later with the loss of the Catherine Adamson, on North Head, the distinctive red and white striped Hornby Light (right), painted to distinguish it from Macquarie Light, was also constructed. Power for the light was originally provided by kerosene, then gas then after the Military took over control in 1933, it was converted into an automated electric light.

|

||

|

Click HERE

|

||

|

Following the end of the Napoleonic war in 1815, many more convicts were sent to New South Wales, with over 1000 arriving in 1818. The impending arrival of ships transporting convicts and an increase in the volume of shipping led to the commencement of a series of building projects in Sydney. Governor Macquarie gave instructions that a lighthouse, the first in Australia, be constructed at the entrance to Port Jackson on South Head. The foundation stone was laid on 11 July 1816.

The lighthouse sat in an area compounded by four stone retaining walls with originally two corner lodges intended for the "keepers of the Signals". The construction of the tower was probably one of the most difficult constructions undertaken in the colony to date. The colony had a shortage of quality building materials and skilled labour which proved to make the construction very difficult. The lighthouse tower was essentially completed by December 1817 but the lantern was yet to be completed as they were waiting the arrival of the plate glass from England.

The lighthouse was operational permanently from 1818 but shortcomings in the construction of the tower became evident early on. The soft sandstone proved short-lived and even as early as 1823 it started crumbling. Large steel bands were placed to keep the structure together and by 1822 it was deemed necessary to carry out emergency structural repairs as some stones had fallen from the arches during that year. Further repairs were undertaken in 1830 and a verandah was added on the western face of the building. In 1873 it was agreed that the light cast by the Macquarie Tower was not sufficiently strong for its important location and that new, more powerful lighting technology should be used, however, the lantern on the Macquarie Tower was too small to accommodate the new apparatus. By 1878 the NSW Government decided a new tower was needed and construction started in 1880, just 4 metres (13 ft) away from the original structure and was officially lit in 1883.

James Barnet was the architect responsible for the project and his design was clearly based on the original. The technology used in this lighthouse (it was one of the first electrically powered lighthouses in the world and also the most powerful) and could be seen from 25 nautical miles out at sea. As such, a higher level of expertise in the maintenance was required as well as a larger number of staff. This led to the construction in 1881 of two semi-detached cottages for the assistants to the Head Keeper. In 1885 new quarters were built for the Engineer and his assistant.

By 1965 the existing garage to the east of the Head Keeper's Quarters had been constructed and in 1970 the 1885 Barnet-designed Engineer and Assistant's Quarters were demolished to make way for the existing row of four townhouses. These originally accommodated the Workshop Supervisor and the Mechanics (Maritime Aids). The road access on the southern side of the site was also constructed during this time.

The station was fully automated in 1976 but the residences remained occupied by staff. In 1980 the Commonwealth Department of Construction carried out a series of works to return the Head Keeper's Quarters to its 1899 form in anticipation of it opening as a museum; however the decision to set up a museum was never taken. In 1989 all staff associated with the Commonwealth Department of Shipping and Transport left the site and a plaque was erected on the site. The Commonwealth leased the Assistant Keepers' Quarters in 1991 and the Head Keeper's Quarters in 1994 as private residences, both for 125 years. The townhouses are now leased as residences on a short-term basis and the lighthouse is leased to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

|

||

|

The spectacular grounds were transferred to the management of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust in 2001 and are now enjoyed by hundreds of people each day.

In 2004, the head keeper's cottage (on the south side) was offered for sale at a price of A$1.95 million.

In June 1838 the NSW Government invited tenders from persons willing to undertake the Mason’s work required in erecting a new Signal House at South Head. This was to the design of Colonial Architect Mortimer Lewis, who had bought and developed a property at nearby Watsons Bay in 1837.

|

||

|

The new signal house (above and below) was a stone building, represented by the two lower floors of the tower that survives today. The two-level building’s foundation was cut 3 metres into the rock above which was built an octagonal building. To complete the renovation project, another tender in January 1841 was invited from persons willing to undertake the erection of a Flag Staff, together with certain repairs to the Semaphore.

|

||

|

Adjacent staff quarters, still occupied, were built from the 1850s. The system of semaphore flags giving details of arriving ships, was replaced in January 1858 using the first electric telegraph line in NSW, which connected the Signal Station with the city. In 1890 the building was raised to its present height of four levels with a signal lamp room above. The fourth floor provides the Signal Station staff with outlooks on all sides, and a door to an outside balcony with balustrade around the building.

The floor, set 85 metres about sea level, has visibility for up to 18 nautical miles. From this fourth-floor observation room is access to the roof space in which is a large signal lamp. In 1892, the Signal House was manned by 4 staff (only one less than at the nearby Macquarie Lighthouse) who lived in the adjacent buildings. The staff included a signal master, an assistant signal master, a telegraph operator and a messenger.

The primary role of the Signal Station remained to observe and report ship arrivals to the city of Sydney and to record shipping movements. The register began in November 1797 and by 1998 it was recording 2800 shipping movements each year. A second function was to advise pilots of vessels arriving so they could go out to meet them. In much of the 19th century the flag announcing a ship was the signal for freelance pilots to race and compete for providing pilotage services. In the Second World War the site was part of the military defences and was responsible for monitoring all vessels approaching Sydney Harbour.

Over the years, different agencies of the NSW Government took on responsibility for the Signal Station. From 1936 the responsible body was the Maritime Services Board. Ship based radio communication reduced the importance of visual observation, but the Signal Station remained to supplement and confirm this and was especially important for smaller vessels. The MSB finally ceased to operate the Station on the 23rd March 1992, relying on their main operation centre at Millers Point together with closed circuit cameras for visual observation. Since that date it has remained in permanent use initially by volunteers from both the Royal Volunteer Coastal Patrol and the Australian Volunteer Coast Guard Association, but now from just the latter. They man radios and maintain visual contact every day, typically for 120 hours a week for the benefit of small and recreational boats. The site has thus maintained its role for over two centuries and from the same building for most of that time.

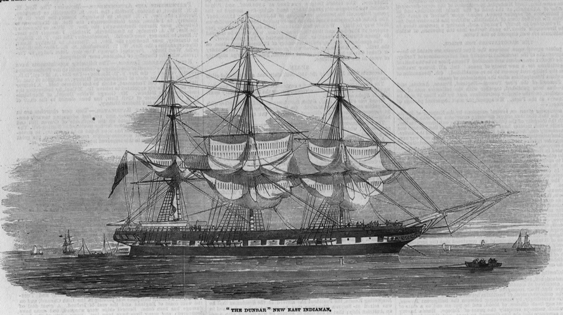

On 20 August 1857 the wooden ship Dunbar was wrecked on the rocks immediately below the Signal Station with the loss of all but one of her 121 passengers and crew. The loss had a major impact on Sydney. The wreck in 1857 is still the worst peacetime disaster to have occurred in New South Wales and is remembered each year by memorial services held at St Stephens Church, Newtown, where many Dunbar victims were buried in a mass grave.

The ship’s Admiralty style anchor was raised and is now on permanent display on the cliffs. Click the pic to read the inscription on the wall.

The doomed clipper Dunbar arrived off Sydney Heads at night on Thursday 20 August 1857 after 81 days at sea. Heavy rain impaired vision, obscuring the cliffs at the entrance to Port Jackson. The Captain had made a number of visits to Port Jackson but on squaring up for the run into port, he may have believed they were overshooting the entrance at North Head and tried to make a quick turn in, however, when the shout "breakers ahead!" was heard, the Dunbar was still south of the entrance almost under the Macquarie Lighthouse. The ship broached and was driven by the swell heavily into the towering black cliffs. Another theory has the officers mistaking "The Gap" for the entrance to the harbour when tacking towards the Heads.

The Dunbar was a well-known vessel that catered for wealthy travellers between Britain and Sydney. The awful scenes that greeted Sydney's population drove home the dangers of long distance sea travel. They witnessed the macabre spectacle of lifeless bodies being flung up against the South Head cliffs. As if in mockery, sharks fought off those trying to recover the dead.

In any event, the impact brought down the topmasts while mounting seas stove in the lifeboats. Lying on its side against the cliffs, the ship began to break up almost immediately. One crewman, James Johnson, found himself hurled onto the rocks where he managed to gain a finger hold. Scrambling higher, he became the sole survivor looking down on a sea of bodies.

Dawn gradually unveiled the enormity of the tragedy. The death toll staggered the population. James Johnson clung to his precarious hold on the rock ledge until the morning of the 22nd when he was noticed from the cliff top. Some 20,000 people lined George Street for the funeral procession on Monday the 24th August. Banks and offices closed, every ship in harbour flew their ensigns at half mast, minute guns were fired and seven hearses and over one hundred carriages slowly moved by. The later loss of the Catherine Adamson just 9 weeks later prompted construction of the red and white Hornby Lighthouse on the tip of South Head, to mark the actual entrance.

The arrival of a French expedition to Botany Bay almost simultaneous to the arrival of the first fleet in January 1788 was a timely reminder that the colony of New South Wales, being the most isolated outpost of the British Empire, was always going to be vulnerable to any military action which might be taken against it. In a world where the countries of Europe were jostling for superiority and control of world trade, Britain had no friends as such, least of all the French with whom the relation was at best unfriendly. From the early days of colonial Sydney, its Governors saw the need to defend Sydney from an invasion by sea. By the city's centennial year, Sydney's defence network had been enlarged to include coastal defences with development reaching its zenith during World War II. Most fortifications of all eras were hastily built, as much to ease the people's minds that something was being done to defend them rather than to establish an efficient defence system. They were under gunned, poorly designed and often outdated by the time they were finished.

Even the fortifications built during World War II were put up quickly and have deteriorated quickly. It is estimated that of about one hundred anti-aircraft and searchlight positions, less than half a dozen remain. Almost none of the hundreds of kilometres of barbed wire laid during the war survives. Only a few air-raid shelters in back yards are known to still exist. The remnants of Sydney's defence system will perhaps never be used again as modern methods of warfare have made them obsolete.

|

||

|

Fortifications were built in 1893 near Macquarie Lighthouse with others at North Bondi, Clovelly, Henry Head and Bare Island (Botany Bay) as part of a coastal defence update. All the fortifications housed 22-tonne 9.2 inch breech loading disappearing guns housed in below ground cavities with concrete walls ten metres in diameter. The barrels of each gun weighed 22 tonnes. The Signal Hill disappearing gun was housed in the centre of three gun pits. It was last fired in 1933 and removed in 1937 when it was replaced by two 6-inch Mk. II guns placed in each of the outer pits. These were removed after World War II. The barrel of the disappearing gun is on display at the Artillery Museum at North Head.

Two levels of rooms were constructed under the gun emplacement in 1915. These were interconnected to bunkers and observation boxes by tunnels also built at the time. (Click the pic at right to see through the door). It's a shame it's not cleaned up and made available to the public.

There are also a number of tunnels and bunkers located beneath HMAS Watson.

The original Outer Battery, which is the earliest of the fortifications on South Head near the Hornby light and old lighthouse keeper's residences, were built in 1859. They are the only fortifications erected on South Head at that time and included a tunnel lined with brick, later covered with concrete.

The cobble-stoned roadway near the top of the steps above Camp Cove is a remnant of the original road constructed in 1871 along which military hardware was transported to the various installation points on South Head. The Inner Battery was built in 1873 and consisted of a series of gunpits and numerous lookout points on the headland from Green Point and Lady Bay. Five guns were aimed across Watsons Bay. A new Outer Battery was erected beyond the Hornby light and facing the ocean and a series of tunnels to connect the inner and outer batteries were cut.

|

||

|

In 1914, the guns were briefly mobilised, but never fired in anger and more bunkers were erected. One has a hand painted 1915 with an upwards pointed arrow (the defence department symbol) above it. During World War II, a new series of tunnels were built linking HMAS Watson to a wharf used to offload military supplies at Camp Cove. These tunnels are quite deep and rather labyrinthine, their entrances today are blocked by steel doors. At the same time, a series of new observation bunkers were cut deep into the cliff face.

These include one which was particularly well placed for viewing the Lady Bay nudist beach.

The view today, looking back into the harbour from the gun emplacements is spectacular.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Over the years there had been frequent recommendations for the fortification of South Head to help defend Sydney Harbour from attack; but fewer actual construction of fortifications and even fewer installations of actual artillery were actually built - until the Second World War. In 1804 Governor King suggested, in order to fortify the harbour, it would be necessary to have a battery of twelve eighteen-pounders on the inner South Head, one side to face the east. The military road built by Governor Macquarie to Outer South Head in 1811 would allow the transport of men and equipment, if required, but no permanent garrison was established. Numerous nineteenth century reports on the defence needs of Sydney Harbour made recommendations that included the fortification of South Head and gun emplacements at Inner South Head in particular, but action on these was slow. Reports recommended the building of a fort, the need for an observation tower, the extension of the military road to the Hornby Light and the installation of a boom across the harbour from Inner South Head.

Some construction of fortifications at South Head may have started by 1841, but fortifications were only completed in 1854, accelerated by the threats of the Crimean War. Then defence priorities were reassessed and it seems no artillery was installed at that time except for a road which had existed from the 1850s from Watsons Bay to Inner South Head. Following the departure of British troops from the colony in 1870, work resumed on fortifications at South Head in 1871 and by 1874 there was actual artillery in place, three 10-inch, two 9-inch and five 80-pounder guns, supplemented in 1878 by torpedo firing stations at Green Point south of Camp Cove. Around 1880 a cobblestone road was constructed from Camp Cove to take equipment landed there by boat up to the fortifications above. By 1887 there was an operating room for Sydney’s defences at South Head. At the southern end of Camp Cove stands the house built by Russian scientist Nicolai Miklouho-Maclay between 1879 and 1881 as the base for a marine biological research station. |

||

|

|

||

|

Despite the excellent location for such a venture the house was taken over in 1885 for military purposes and became the property of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1908. It was mainly used as an officers’ residential quarters until 2001, after which it was handed to the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and since has been used a private residence. At Federation there was a large but ageing array of artillery established as Sydney’s defences, but by 1911 this was rationalised and with greater emphasis on South Head, which still had 8 of the 20 guns in position and two more not yet mounted. Though manned in the Great War, they were given little strategic priority. The military acted to close South Head to fishermen and the School of Artillery near Gap Bluff from about 1895 to 1938 had its own practice batteries.

The military training establishment HMAS Watson, lying between Inner South Head and the Gap Bluff, was established in 1945, incorporating the Naval Radar Communications Centre at Gap Bluff.

HMAS Watson is now Australia’s major maritime warfare training base.

The Army’s School of Artillery/Gunnery was relocated on the headland from Middle Head in 1894–95, both for training and for practice. The buildings used for training were extended in the late 1930s but the practice battery was made non-operational in 1938. In 1941 the training centre was moved back to Middle Head and the buildings were used for other military purposes. The Navy’s Radar Communications Centre had extensive buildings at Gap Bluff and national servicemen were accommodated on the site during the Vietnam War. After military use ceased, the site was handed over to National Parks in 1982. Surviving buildings include the former Officers’ Mess, Artillery Cottage, toilet block and Armoury.

|

||

|

The former Officers Mess building, front and back, now in rundown condition. |

||

|

Trainee gunners from Australia and New Zealand attended the School to learn the principles and practice of moving, mounting and firing large guns.

The oldest building on the site, the Artillery Cottage (below), is currently used as a care-taker’s residence. Built in 1895 it stored ammunition for the Gap Bluff practice battery.

|

||

|

Some of the School’s first graduate gunners served in World War 1, at Gallipoli and in France while the site’s last graduates served in World War 2, both overseas and along the Australian coastline. All that remains of the large barracks complex, which once covered the site, are concrete footings, the buttressed retaining wall at the rear of the site and the toilet block.

|

||

|

The old Armoury building (above) is now a function centre.

|

||

|

The original toilet block is all that is left of the accommodation and administrative buildings that once dotted the site. Originally for Officers one side, men the other, it then became men one side women the other and if a glass window (one-way of course) was put in the wall it would become “The Loo with a View” as it has a billion dollar outlook. (See below).

|

||

|

|

||

|

Part of the immaculately kept grounds on which the Artillery School once stood. “The Loo with a View” is on the left with the Officers' Mess just visible in the background, just to the left of the roadway.

Just a small distance further north along the point lies the Navy’s HMAS Watson.

|

||

|

HMAS Watson is the Navy’s premier maritime warfare training establishment and in 2010 it celebrated its 65th anniversary as a commissioned Naval base. Situated on the South Head of Port Jackson, Watson’s role is to prepare RAN officers and sailors to fight and win at sea.

One thing we did notice is the new state of alertness the ADF is adopting, gone is the 5 stage Safebase Alert system which has been replaced by the 3 Stage levels, Aware (Security aware, normal business), Alert (Increased security, restricted business) and Act (Follow emergency procedures).

If you've got nothing to do click HERE and after you've read the whole 595 pages you'll know all about Defence Security.

South Head was immediately recognised as an important site for the young colony and, as early as the first year of settlement, a signal gun from Sirius was installed at South Head in order to indicate the arrival of any seagoing vessels. The gun, along with Sirius’ anchor, has been displayed at Macquarie Place in Sydney’s Central Business District since 1907. Notwithstanding this interest, the signal station and a look-out post, established in January 1790, were the extent of the defences at South Head for the first half of the nineteenth century.

South Head’s maritime connections grew over the course of the nineteenth century as many of the colony’s pilots as well as the pilot ship, Captain Cook, were based at Watson’s Bay, and wharves and navigational aids were constructed. The area also became home to fishmongers, charter companies and ferry services.

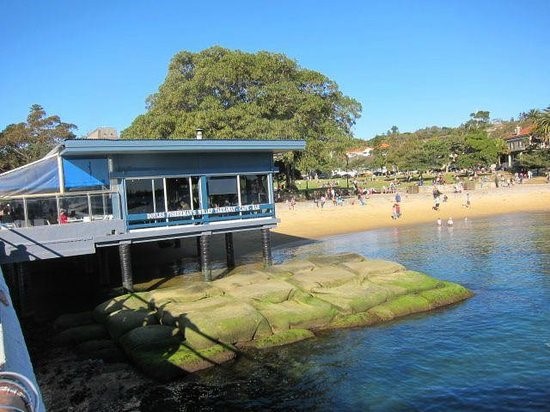

The Sydney Lifeboat Service was established in 1858 in the wake of the Dunbar and Catherine Adamson disasters. Watson’s Bay became home to the Port Jackson lifeboat, Lady Carrington, in 1880 which was replaced in August 1907 by the 37-foot Alice Rawson (right) which was based at Gibson’s Beach, directly in front of the Watsons Bay Hotel and where Doyle’s seafood restaurant sits today (below).

|

||

|

|

||

|

South Head remained largely unaffected, from a defence perspective, by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Indeed, the defences of the area remained largely unchanged until the outbreak of World War II when further gun emplacements were installed at various points around the Bay and the wharf at Watson’s Bay was extended to accommodate an increasing number of warships.

On 16 February 1939, the RAN’s Anti-Submarine School was established at the

Edgecliff Depot on nearby Rushcutters Bay, an area which became an integral

part of Watson’s story in the following decades. First commissioned as HMAS

Penguin (II), the depot became HMAS Rushcutter on 1

Officers’ courses consisted of instruction in electrics, the theory of ASDIC (an abbreviation of Allied Submarine Detection Investigation Committee and later known as SONAR, itself an abbreviation of Sound Navigation and Ranging). Anti Submarine (A/S) training continued after WWII at a reduced rate and allowed the amalgamation of the Torpedo, Mine and Anti-Submarine Schools into the Torpedo and Anti-Submarine (TAS) School in 1948.

The RAN first became a large, and important, resident at Watson’s Bay in 1942 when the Radio Direction Finding (RDF) School was established there. The adaptation of radar for naval purposes necessitated the training of RAN personnel as operators and technicians, as well as the provision of radar sets, spare parts and stores for personnel and ships in the Pacific area. Preparations to provide radar training in the RAN began in August 1941, and after brief periods at Rushcutter and aboard HMAS Australia (II), the RDF School was formally established at South Head on 1 July 1942.

The RDF School occupied buildings at Gap Bluff that had previously been part of the School of Artillery. The original establishment consisted of an office block and classrooms. A power house and operations block was completed in August 1942 along with the School’s first actual radar sets. The majority of staff were RAN members with radio or radar qualifications and many of the original complement were members of the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS). The RAAF also provided eleven officers and men to assist both with instruction and the fitting and maintenance of the equipment.

Initially there was no on-board accommodation for sailors at the RDF School, who were either accommodated at HMAS Penguin or were provided with an allowance to live elsewhere. This proved to be very problematic as sailors had to be transported to South Head each day and were subject to the vagaries of the weather and wartime public transport. The provision of on-site accommodation towards the end of the war proved to be immediately beneficial.

|

||

|

|

||

|

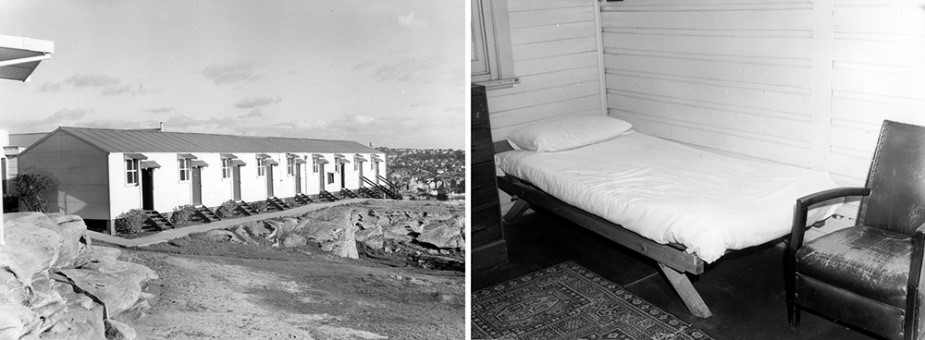

Left: An officers’ cabin block at HMAS Watson, circa 1959. Right: An example of the very spartan officers’ cabins in 1959. They were draughty, damp and very uncomfortable.

On the 14th March 1945, the South Head facility was commissioned as HMAS Watson, named not only after Watson’s Bay but also to commemorate Sir Robert Watson-Watt, one of the inventors of radar. With commissioning came approval for further construction including messes, sleeping quarters and classrooms. With the influx of personnel that came with the arrival of the BPF Watson was often filled to capacity, and even after the war it remained an important Commonwealth training establishment. More than 100 RNZN sailors received radar training at Watson in the period up until 1953.

More than 2200 RAN officers and men were trained at the School during the course of the war.

After the war, Watson also became the primary training facility for Action Information Organisation (AIO) teams. The AIO can be described as the tactical brains of a ship, for it is here that engagements are plotted and tactical decisions made. Without adequate simulation facilities, trainees initially visited ships of the Fleet to gain practical experience. This situation changed when the Action Information Training Centre (AITC) opened at Watson in May 1952. Designed to provide warfare officers and sailors with tactical training and experience under conditions close to those found at sea, the AITC became one of the primary training tools for AIO teams.

Expansion continued as construction for the Torpedo and Anti-Submarine (TAS) School began in 1954 and the School itself moved from Rushcutter to Watson two years later bringing with it the need for more administration, accommodation and amenities blocks. When the TAS Branch moved to Watson the administrative section of the Clearance Diving Branch came with it. Clearance Divers became, and are today recognised as, the RAN’s elite combat unit and face some of the toughest training offered in the Australian Defence Force.

Watson also became the training centre for one of the most important, and

one of the most overlooked, aspects of any defence force: cooking. The

School of Advanced Cookery was located at Watson for over a decade and

conducted courses and lectures for seamen cooks to advance in their area of

expertise. The cooks held regular public and industry demonstrations and

were a popular attraction at Watson Open Days and Navy Weeks. The School

also conducted trials on new equipment and ingredients, from powdered eggs

to deep fryers and microwave ovens, to assess their

By the end of the 1950s, Watson possessed some of the most modern facilities in the RAN and they were proudly put on display when Watson opened Navy Week in October 1959. Watson continued to develop into the new decade with a tender for a new Wardroom accepted in December 1960 providing accommodation and associated facilities for both senior and junior officers.

The inter-denominational Chapel of St. George the Martyr was completed in 1961

With significant upgrades to the training facilities having been carried out over the previous decades, much-needed upgrades to living accommodation were conducted throughout the 1990s. A group of dilapidated but heritage listed buildings on the base were refurbished as six new married quarters and occupied on 1 February 1991. The Wardroom also underwent renovations in 1993 while renovations to the junior officers’ accommodation were completed in January 1994, just in time for the arrival of new Australian Defence Force Academy graduates. The junior sailors’ bar, canteen and credit union also underwent significant refurbishments early in 1994. The Watson Health Centre was also extended and refurbished in 1994-95, and offices were refurbished for the Naval Reserve Cadet Logistics Support Cell.

|

||

|

Senior sailors accommodation at HMAS Watson today.

Today HMAS Watson has deservedly earned its reputation as the RAN’s premier warfare training establishment. Its state-of-the-art facilities are, today, spread across nine departments and Watson is internationally recognised as offering some of the finest naval warfare training anywhere in the world. Watson now provides basic and advanced training for Junior and Senior Sailors in the Combat System Category and Junior Seaman Officers in ship handling, navigation and tactics.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Because of its extraordinary physical beauty sightseers have always flocked to Watsons Bay, with a regular ferry service beginning in the 1870s, leading to the establishment of a number of hotels as well as the tea rooms which later became Doyle's Restaurant. Once the place to eat and to be seen, Doyle’s has lost a lot of its shine and is now just another fish and chipper which is hardly ever open.

|

||

|

|

||

|

One place that is definitely worth a stop-over is the Watsons Bay Hotel. Established back in 1883, and once owned by the Doyle family, it was sold for $30M back in 2012 and on a fine day you would have to go a long way to beat an afternoon in the beer garden, with a cold one or two, looking out over the bay with the ferries coming and going.

We loved it.

|

||

|

|

||

|

As lovely as it is, Watsons Bay had a reputation as a well-known place for suicides in Australia. The tall cliffs have made it a location for those wishing to end their lives. Between 2008 and 2011 numerous measures have been implemented to dissuade those at risk of suicide, these include security cameras to monitor the area, several purpose-built Lifeline counselling phone booths, and information boards from the Black Dog Institute and Beyondblue. An inward-leaning fence has also been erected to deter people from jumping.

|

||

|

The cliff areas around Watsons Bay, with the old Army Officers Mess building top left..

|

||

|

On the afternoon of 20 April 1936, noted Australian diarist Meta Truscott recorded how she and her uncle, Christopher Dunne, witnessed a suicide at The Gap. By chance, the pair shared a bench with a well-dressed, middle-aged man who was later identified as William Albert Swivell. As the three watched a ship sail through the Sydney Heads, her uncle asked the man if he knew its name, to which Swivell replied, "The Nieuw Holland." Soon afterwards, the smartly-dressed man stood up and walked away; he climbed to the top of the cliff and jumped to his death.

In June 1995, a 24-year-old model, Caroline Byrne, fell to her death at The Gap. Due to the notoriety of the area, police did not initially suspect foul play. However, in 2008, her then-boyfriend was convicted of pushing her over the edge. He was later acquitted of murder in February 2012. In November 2007, Charmaine Dragun, a 29-year-old newsreader who worked for 10 News First, jumped from The Gap after battling depression and anorexia.

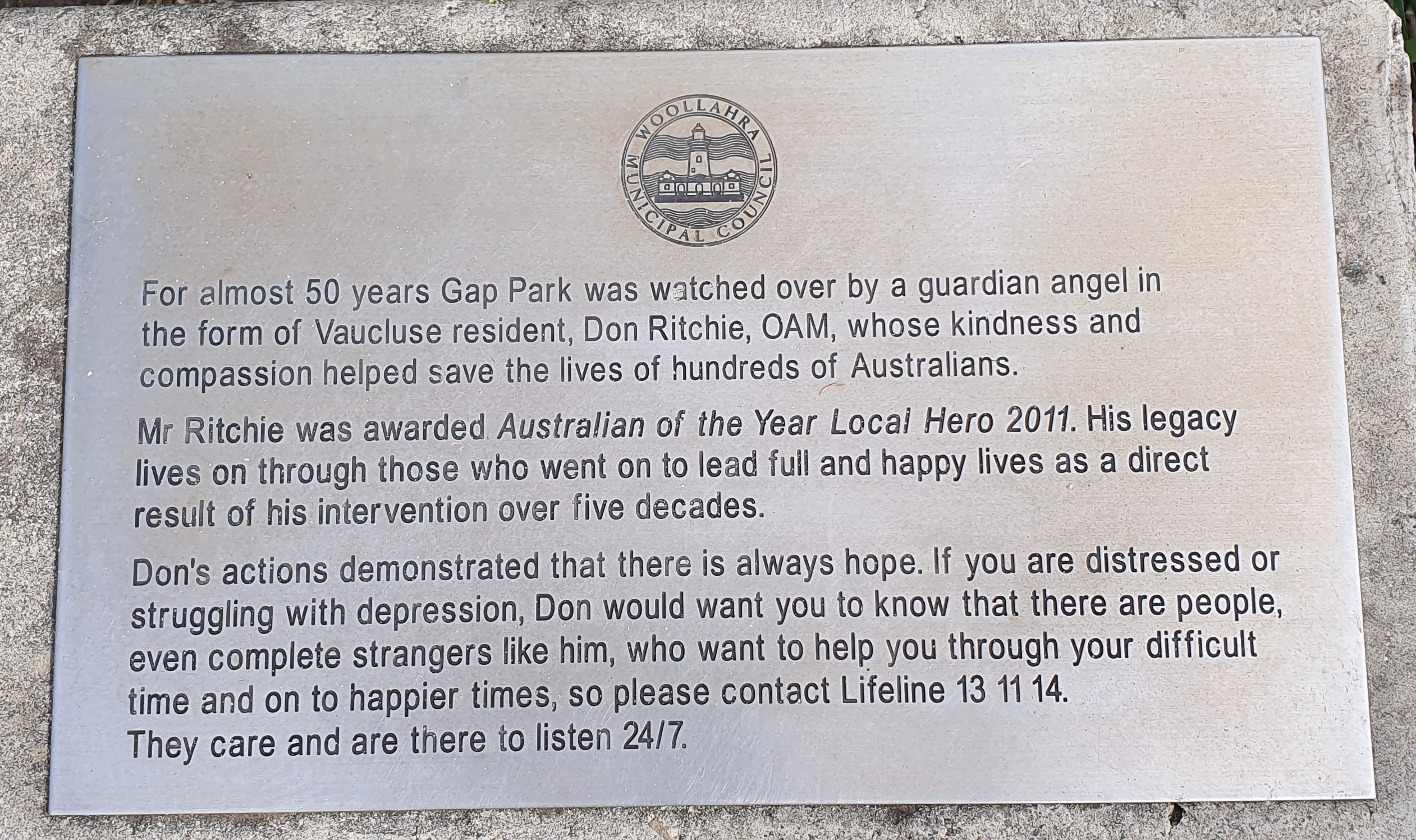

In 2009, Don Ritchie, a former Second World War Naval veteran and retired insurance agent, was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for preventing suicides at The Gap. From 1964, Ritchie saved 164 people from jumping from the cliffs by crossing the road from his property and engaging them in conversation, often beginning with the words, "Can I help you in some way?" Afterwards Ritchie would invite them back to his home for a cup of tea and a chat. Some would return years later to thank him for his efforts in talking them out of their decision. Ritchie, who on the afternoon of 20 April 1936, noted Australian diarist Meta Truscott recorded how she and her uncle, Christopher Dunne, witnessed a suicide at The Gap. By chance, the pair shared a bench with a well-dressed, middle-aged man who was later identified as William Albert Swivell. As the three watched a ship sail through the Sydney Heads, her uncle asked the man if he knew its name, to which Swivell replied, "The Nieuw Holland." Soon afterwards, the smartly-dressed man stood up and walked away; he climbed to the top of the cliff and jumped to his death.

|

||

|

In 2009, Don Ritchie, a former Second World War Naval veteran and retired insurance agent, was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for preventing suicides at The Gap. From 1964, Ritchie saved 164 people from jumping from the cliffs by crossing the road from his property and engaging them in conversation, often beginning with the words, "Can I help you in some way?" Afterwards Ritchie would invite them back to his home for a cup of tea and a chat. Some would return years later to thank him for his efforts in talking them out of their decision. Ritchie, who was nicknamed the "Angel of The Gap", died in May 2012.

A plaque was installed on the pathway in his honour.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

suitability for the Navy. If, as Napoleon once said, an army marches on its

stomach, then likewise, a navy sails on its stomach and the contribution

that the School of Advanced Cookery has made to the RAN should not be

underestimated. The school was closed in May 1966 and moved to HMAS

Cerberus.

suitability for the Navy. If, as Napoleon once said, an army marches on its

stomach, then likewise, a navy sails on its stomach and the contribution

that the School of Advanced Cookery has made to the RAN should not be

underestimated. The school was closed in May 1966 and moved to HMAS

Cerberus.