|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

My Story.

|

||

|

This story contains a number of "abbreviations". In some instances you can click a link which will take you to the "long version" of the abbreviation. To then return to where you were reading, click the back button on your browser.

|

||

|

Ian “Tiny” Ashbrook.

In Part 2, Ian Ashbrook had just been posted from RAAF Williams to Adelaide where, in Jul 1992 he was tasked with forming the Defence Centre at Keswick Barracks under the Defence Regional Support Review (DRSR) framework with the ultimate aim being to reduce duplication of Defence services within the State.

Under DRSR, in each of the States, the Army Military District (MD) Commanders were effectively replaced by a Head of Defence Centre (HDC) representing both the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) and the Secretary. This was implemented progressively and, until my appointment, which was the second last, all appointees had been Army. I was appointed to South Australia and the final appointment some time later was a Navy Cdre in Sydney. One minor exception to this was the Northern Territory which was left alone until the Northern Command (NorCom) restructuring was substantially completed and in 1994, Commander Norcom (then AirCdre Peter Nicholson) took on a secondary role to implement DRSR in the NT. Until my appointment, the process for Army had been rather transparent with the Defence Centre Heads largely taking on the Military District Command roles; but, when I took over in Keswick Barracks, Army suddenly faced a similar situation to what I had faced with Brig David Noble trying to implement DRSR in Vic.

I started at Keswick in Jul92 with the aim of full transition to the Defence Centre (DC) by 1Dec92 and, during this time, in addition to trying to establish a framework with the 3 Services and the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) at Salisbury for DRSR, I worked with the outgoing COMD 4MD, Brig Peter Bray to review Army functions and assets and determine how they would be managed after 4MD disbanded and DC-Adelaide (DC-A) came into effect. Naturally the latter was difficult for Army as, post DRSR, the most senior permanent Army officer in SA would be a LtCol (Wing Commander equivalent), although the Reserve Battalion (9 Brigade), commanded by a Reserve Brigadier remained in Adelaide. Negotiations also commenced with Navy and AirForce as well as DSTO and Woomera and it was decided to defer the latter two until the former had been progressed; however, concurrently the civilian functions in the State were also reviewed and, by agreement with the Defence Secretary (Tony Ayers) these were all transferred under HDC-A from the formation on 1Dec1992 and the State Defence Regional Secretary then became the Deputy Defence Centre Head

Essentially, in addition to the DRSR function I initially took on much of the MD Commander role which was interesting. This was at the very early stages of tri Service integrated management and I was the only non Army officer in Keswick Barracks albeit, fortunately, at the top of the tree. Naturally this caused some consternation and there was understandably some significant reticence to my presence. This was evident in many small things. In Jan 1993 I received an envelope in the in tray advising me of my 'Honorary Membership of the Keswick Barracks Army Officers Mess'.

The mess had been largely furnished by a benefactor (including the heavy red curtains) - the rather wealthy (drove a Rolls-Royce and lived in a mansion up in the Adelaide hills) and a bit eccentric widow of a former Commander (Brigadier) of the Reserve Battalion. Initially I found this lady a bit imposing but, as time went on we actually got on very well, became good friends; but, it was just another complexity with the Mess.

|

||

|

|

||

|

After checking the Defence Instructions on messes, I called in the legal officer on the HQ Staff and asked her what she thought? After an initial moment of embarrassment, she indicated that she knew that it was only a matter of time before this subject came up and that shortly before my arrival a general mess meeting had been called at which the name of the Keswick Barracks Officers Mess was changed to Keswick Barracks Army Officers Mess and only Army officers could be full members. Of course, this flew in the face of the Defence Instructions and while I was contemplating how to address the matter the Commander of 5 Brigade (Brig David Rowe) the Army Reserve Unit called on me, asked what I intended to do and suggested that he request that a mess meeting be called at which he would propose reverting to Keswick Barracks Officers Mess etc and that I not attend the meeting. This duly occurred and the new mess sign was replaced by the old one. But, this wasn't the end of it. Some time later the Chief of General Staff (CGS) (now designated Chief of Army) rang me to express some strong views on the mess and, in frustration, I asked whether he thought I was going to sell the mess silver and replace the paintings with those of aircraft. We agreed that it was a Defence mess with an Army heritage and I assured him that I would leave it at that.

Until Peter Bray moved from the appointment house in Dec we had rented a house in Dulwich and, when he moved, Defence Housing Australia (DHA) commenced some long overdue major maintenance mainly due to rising damp; so, it was not until late Apr93 that we finally moved into Flagstaff House from our temporary accommodation. From early in our arrival in Adelaide and on learning that we were Eastcoasters we were inevitably regaled with the 'you must understand, there were no convicts here only free settlers' and 'the SA Army was privately funded prior to Federation'. As I have mentioned, Adelaide was an Army town with some 2000 Army Reservists then serving, many in the community had served and nearly everyone we met had friends or relatives who had served in the Army Reserve and they were very parochial and protective of that Army; so, a 'blue shirt' in town was viewed with some suspicion, especially an 'outsider' blue shirt whose role was to reduce numbers and implement savings.

During this time I continued to return to Laverton to fly the Vampire and when the Adelaide Grand Prix was held in early Nov 1992 I was asked to display it over the track. Adelaide had a street track through the city so this posed some safety issues with CAA; but it was eventually approved, provided I stayed above 1000ft. I did this; but, I may as well have been on the moon as it was so far away from the action. I normally displayed at 100ft straight and level through to a max of 60 deg bank not below 300ft; but, of course this was inappropriate for the city. Notwithstanding, we received a great deal of positive publicity and the display was appreciated. Some time prior to the Grand Prix, AirCdre (later AVM) Neil Smith, then OC Pearce, contacted me and asked if there was any possibility of bringing the Vampire over to the West for their large Base Open Day and to celebrate 25 years since the Vampires had been retired from Pearce.

This was held on the weekend after the Grand Prix; so, we kept the Vampire at Edinburgh and planned the long journey to the West refuelling at Woomera, Forrest and Kalgoorlie but, at the last minute Woomera became unavailable due to a USAF C141 parked on the only runway and, following some quick reassessments, decided to transit via Ceduna instead of Woomera. My 'ground crew' for the journey was SqnLdr John Haynes (SEngO at 21 Sqn) who had been heavily involved in the restoration of the Vampire and its subsequent operation and, as we commenced our descent into Ceduna John asked where the runway was and I pointed out the long gravel strip on the nose. 'You aren't landing my Vampire on a gravel strip he yelled'. To which the only response was, 'Where else would you like to go, John? This is the only runway within cooee'.

The forward flights were done in one day on the Sat and timed for us to arrive at Pearce directly into a display prior to landing. At Kalgoorlie we were marshalled onto a freshly laid tarmac apron in front of the terminal building and when I wanted to shift the aircraft prior to the subsequent start the airfield manager was insistent that this not be done and that I started where we were.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Now the Vampire exhaust is angled down and very hot and the aircraft cannot be stopped on tar without melting it and I emphatically explained this; so, when we subsequently got airborne and I saw the huge scorch mark on the apron I was aghast and expected some council repercussions; but, although I waited with some trepidation for these to come in the coming months, nothing ensued.

I had to be in Canberra by the following Mon night so, on the Sun we flew over Perth in the morning and did an early display and then timed the afternoon display such that we departed for Kalgoorlie without landing back at Pearce and subsequently overnighted in Forrest with the towns five permanent residents, an evening to remember. I subsequently continued to return to Laverton to fly the Vampire and did airshows at Williamtown, Nowra, East Sale. Tamworth etc as well as all of the Avalon International Airshows. In fact for Avalon 1992, which was in Oct before the DC came on line, I managed to time it such that I was part of either a 6 or 8 ship Winjeel formation out of Point Cook in the morning, then peeled off and landed at Avalon to provide the Winjeel static display for the day, flew the Vampire display at Avalon in the afternoon and then avoided the traffic by flying the Winjeel back to Point CooK late in the afternoon.

After the DC came on line in Dec92 we commenced the rationalization process in earnest and there were many arguments on the transfer of funds, provision of vehicles, recording of personnel numbers, facilities allocation and maintenance etc etc. One moment of light relief was when I was summonsed to Canberra for the quarterly Army Commander's Conference chaired by the Deputy Chief of the General Staff (DCGS). All MD Commanders attended this conference and as the DC heads were all Army this had just continued transparently. The conference proceeded apace with the Army hierarchy at the main table and the remainder of us seated in the shadows. Towards the end, I think in general business, one of the Generals suddenly asked 'what are we going to do about this Air Force chap in Adelaide' which evoked some passionate conversation and they had clearly forgotten about my presence in the shadows. To save any further embarrassment the only thing I could think of was to call out in a raised voice something along the lines of 'oi you're talking about me'. DCGS immediately saw the problem and, like the Dassault man in Paris in 1978, responded with 'I think it a good time to break for lunch'. I was not invited to another Commander's Conference.

Early in 1993 I received a call from the Secretary (Tony Ayers) to discuss the management of the town of Woomera and, more importantly, the Woomera Protected Area (WPA) which was particularly politically sensitive and encompassed a land area of about one sixth of South Australia extending widely across Aboriginal lands. The result of this was that I took on responsibility for both the town and the WPA. From its heyday at the height of the 50's and 60's testing, the town of Woomera was down to a population of about 1200, most of whom were Americans and their families operating the tracking station at Nurrungar not far out of town.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Woomera had been a closed town with controlled access; but, while this had been done away with, the town was a Defence establishment funded solely by Defence and managed on site by the Area Administrator (AA). The AA when I took over was Alan Lockett who had been AA for over five years. I had known Al for many years he being a former RAAF WgCdr navigator who had been with the F111's at introduction and was a great 'can do' man with a fine intellect. We got on very well and when soon after my civilian deputy at the DC moved on Al applied for the job and, with his Woomera experience alone, was a shoe in. But the problem then became how to replace him at Woomera. The job had significant responsibilities; but, in the public service pay structure this could not be recognized and we had considerable difficulty finding someone of the right calibre prepared to relocate to the isolation of Woomera and accept the responsibilities for a relative pittance. This was exacerbated by the similar position at Roxby Downs, the town for the Olympic Dam uranium mine some 60 km from Woomera being remunerated much more highly and initially we had quite a long period with temporaries and I depended on Al for his knowledge of Woomera.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Soon after the total responsibility for Woomera and the WPA was transferred under me, I received a call from Al who was still Area Administrator to brief me that it was Nurrungar's 'turn' for the annual Easter protests by the anti-nuclear etc group. This loose grouping of protestors alternated their Easter protests between Nurrungar and the other joint US/Australian base Pine Gap near Alice Springs and in 1993 they determined to take a significant stance in anticipation of closure of the bases.

Expectations were in excess of 1000 and they aimed to set up a rough camp close to the Nurrungar facility and attempt to penetrate the perimeter. Clearly prevention of this was way beyond the SA police and Defence Force personnel in the area so I consulted with the Police Commissioner (David Hunt), who had experience with previous protests and the police presence at Woomera was significantly supplemented and we deployed more than 100 Army personnel to be based within the site to provide a last line of defence should the triple barrier be penetrated. I then also went up to Woomera for the period as an observer. In the event, an estimated 700 turned up comprising men, women and children and many arrests were made. As planned, those arrested were bussed to Port Augusta (180km away) where they were processed; but, on release, soon made their way back in buses supposedly funded by the CFMEU! Numerous attempts were made to penetrate the base; but, fortunately none were successful. Inside the base, we were able to accommodate the Army out of sight within the large antenna domes while the police had also deployed a mounted section who could access the difficult terrain around some sections of the base.

In my initial introductions, I met many of the senior people with whom I was to interface, at a cocktail party arranged by Peter Bray, who used this also as one of his farewell functions. When the senior naval officer Cmdr Brian Gorringe was introduced he said something along the lines of 'you don't remember me; but, I know you from way back' and left it at that. I caught up with him later and it turned out that he had also been raised in Port Moresby and that his father had bought from my father the Austin 7 that had served us so well when our family returned to Port Moresby after the war. Brian had also attended the same boarding school as me; but, several years behind me.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Navy presence in Adelaide was small mainly associated with the Collins submarine build (the first of which was launched while we were in Adelaide), ship visits and Naval cadets. Brian Gorringe reported to RAdm Tony Hunt the Navy Support Commander who I had known from Canberra and despite some initial and expected pushback, we managed to agree to Navy moving into Keswick Barracks making their facilities available for disposal. Adelaide was a popular port for ships visits so we attended many on board receptions and on one particular occasion Brian arranged for Carolyn and I to board an Oberon submarine out in St Vincent Gulf and spend several hours aboard as we made our way into Adelaide.

In many respects Adelaide was like an overseas posting for us, having no relatives and few close friends in SA and being far enough away from the East coast to make it feel like a separate part of the world. SA was also unique with the wide range of geography and the huge expanse of desert country. Of course, this was made more interesting by having a close association with Woomera. Soon after accepting this responsibility I sought approval to replace my work vehicle with a 4wd SUV and insisted where possible that senior visitors wanting to visit Woomera flew into Adelaide from where I would drive them to Woomera. Prior to this, Canberra visitors invariably flew directly into Woomera and then moved from air-conditioned car to air conditioned office to air conditioned accommodation etc. By driving up, not only could I show them part of the large Army training range, Cultana, that stretched down Spencer Gulf from Port Augusta almost to Whyalla; but, also some critical infrastructure in addition to ensuring that they understood what desert heat meant.

|

||

|

|

||

|

When Woomera was being established attempts were made to locate water in the Great Artesian Basin; but, to no avail, necessitating the construction of a pipe line from Port Augusta to Woomera as the only source of water for the town and Nurrungar. This pipeline depended on a number of pumping stations to pump the water the nearly 200km from Port Augusta and if one of these failed, the town had less than a week's water reserve. So, I had a route that took visitors off the highway to one of these large pumps and it gave me the opportunity to emphasize that if one of them had a catastrophic failure then we would urgently need up to $1m for a temporary pump and to effect a replacement. Another innovation, for selected visitors overnighting, was to dine at Spud's Roadhouse at the intersection of the Stuart Hwy and the Woomera turnoff, a few kms out of town. This was to emphasize the isolation of Woomera with the next closest cafe/restaurant being at Port Augusta nearly two hours drive away. To my surprise, I had no objections from any seniors to this drive, even though it took nearly five hours each way.

|

||

|

|

||

|

For some years, an interested group from Woomera had been conducting ventures into the Simpson Desert to locate, mainly for historic and museum purposes, various pieces of equipment that had landed there from tests over the years. The entrepreneur, Dick Smith, had provided some assistance and In May 1994 a group formed to attempt to recover some bits located by Dick for which he had recorded the GPS coordinates. Over a few beers I expressed interest in joining the group and we also invited the Nurrungar Commander COL Jack Harris, USAF and his wife, Lynn, to participate. Carolyn had reservations; but, was encouraged by Lynn's participation, despite the query 'how will I dry my hair'? To which the response was simply 'no problem we won't have enough water to wash it anyway'. That said, Carolyn reluctantly joined in; but, at the last minute the Harris's pulled out leaving Carolyn as the only female which didn't please her. As it happened, I had to go to the UK on private business just after the trip so Carolyn bargained that she would go into the desert on the condition that she then come to the UK and we make a holiday of it.

Soon after I had got the 4wd for work, GpCapt Garry Kirk (CO Base Sqn at Edinburgh) suggested that a few of us do a RAAF 4wd drive course which we did over a weekend in the Flinders Ranges. This proved to be invaluable, not only for the Simpson; but, also for general use throughout the State. For the Simpson crossing which was S-N through the sand hills (around 100) away from the E-W tracks that had largely been created for oil exploration and requiring fuel, water etc for about 10 days, we had five vehicles and 10 participants. After tracking from Woomera to the Oodnadatta track we made our way through William Creek, where a number of recovered pieces of trial equipment had been located under the auspices of Al Lockett when he was Area Administrator and on to Oodnadatta. Unfortunately, I started to have numerous tyre problems with the tyre cases cracking and pinching the tubes. When we eventually returned to Adelaide the tyre company acknowledged that they had had a bad batch of tyres and replaced them; but, this was of little consolation when we were in Oodnadatta and trying to make a decision on continuing into the desert. In the end I bought several 'used' tyres as no new ones were available and we pressed on up the dry Macumba River and out into the Simpson for some 10 days. This was a great experience dragging and snatching the vehicles over the sand hills and especially when we located what we were looking for. Finally, we made it to the Rig Rd between Birdsville and Dalhousie Springs and turned west to enjoy some relaxation in the warm artesian waters of the Springs. In the end Carolyn actually enjoyed this unique experience so much that she admitted feeling guilty on the way to the UK a week or two later.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Meanwhile, in Adelaide we pressed on with the Review and I had to admit that as in my previous job defending RAAF at Williams, had I been on the other side I would have been arguing as hard as possible against much of what we were doing, although in the big scheme it was required. Nurrungar also brought some unique experiences especially with the biannual reviews with USAF Space Command which alternated between Woomera and Colorado Springs with an opportunity to enter the US nuclear bunker within Cheyenne Mountain. At the same time we were under pressure to outsource to contractors many functions not only in the Adelaide area; but, also in Woomera and Al Lockett did a sterling job in both places.

Another very interesting function was as a member of the State Emergency Committee chaired by the Police Commissioner (David Hunt) and involving the heads of key SA government departments along with the Premier. Adelaide lies on the same seismic fault line that produced the earthquake at Newcastle in 1988 and much effort was devoted to planning for such an occurrence as well as bushfires etc. Army had significant assets in SA which would have been employed in most scenarios, with the biggest worry to us all being communications. Mobile phones were only just coming into regular use; but, like other wireless communications depended on aerials for transmission and reception and ensuring that we had sufficient redundancy, portability and power distributed around Adelaide in the event of a disastrous earthquake was a major consideration.

I spent a lot of time with the Police Commissioner on a range of joint responsibilities and we became friends culminating in us, with another two couples, holidaying in Italy some time after I had left Adelaide. In many respects, this was a unique experience as we learnt on arrival in Rome when we were all met at the airport by the resident Australian Federal Police (AFP) representative from the Aust Embassy and conveyed into the Embassy prior to collecting our holiday vehicle. The Police Commissioner was required, as a courtesy, to advise his counterpart in Italy of his movements and he was then contacted by the local Carabinieri senior officer as we moved around. This, of course was very helpful where, for example, at Lake Maggiore, where the castle on an island in the lake had just closed for the winter, we were taken there on a Carabiniere boat and the castle was magically reopened for a private tour.

|

||

|

|

||

|

However, the best experience of this was in Rome where, on return, we checked into a pretty standard, but well located, three star hotel where, as tourists, we were treated with a somewhat haughty disdain by the staff. That evening, however, we had all (at this stage three couples) been invited to dinner with the Carabinieri Generals in their exclusive mess and at the appointed hour two black unmarked Alfas pulled up on the footpath outside the hotel and we were conveyed to the Mess by a circuitous route through the back streets of Rome. The dinner was a magnificent, although a little hard for our wives as, while the generals spoke fluent English, conversation with their wives was a little more difficult. On the return to our hotel, the attitude change was amazing as clearly the staff could not connect a bunch of Australian tourists to the Carabinieri. On following days, our transport was similar as we (the 3 men) were escorted to, amongst other areas, the main Rome operations centre and briefed on undercover operations and the involvement of our AFP. I had spent time in the SA police operations centre so had some familiarity with the environment; but, the Carabinieri with their air, sea and land assets operating in a para military organization was an eye opener.

However, towards the end of 1994 I became aware that my next posting was imminent and then learnt that, after a career of having, not deliberately, avoided a HQSC posting, that I was to take over as the Director General of Logistics Operations (LogOps) at HQ Logistics Command (HQLC - the successor organization of SupCom) in early 1995. Initially I sought to remain in Adelaide as we were only just getting on top of Regional Support and continuity was essential to maintaining momentum; but, this was unsuccessful. So, after a minor delay for eldest son Paul's wedding in Bowral in early 1995, we moved back to Melbourne where the only Defence house available was in Werribee and HQLC was still in St Kilda Rd where I enjoyed a corner office with a grand view overlooking Port Phillip Bay from the 24th floor. But, this was short lived as the Command moved to Laverton a few weeks later into the now vacated Radschool building where, if I stood on tip toes, I could catch a glimpse of the Laverton parade ground from the elevated windows!!

LogOps was responsible for providing the support to the operational Air Force with a budget of just over $0.5b ($500m) which sounded substantial but, I was soon to learn was about 20% underfunded. I was fortunate again to have some very experienced officers in the group, particularly GpCapt Brian Duddington (right) who had had a wealth of experience coming up through spares assessing and repair and overhaul and was currently undertaking studies into baseline funding which gave us much better visibility into the funding requirements. That said, at the end of the day the hard decisions were for those requirements that just could not be funded. I had always been uncomfortable that these decisions were largely determined by staff officers in HQSC who, in turn, were criticized for failing to provide what had been requested and felt that responsibility for such decisions should involve the officers at the operational end.

It was around this time that the Force Element Groups (FEGs) had come into being under the Air Commander Australia and their individual support was being provided by the Weapons Support Logistics Management Squadrons (WSLMS) whose COs reported directly to the AOC Logistics Command. Funding bids were determined by the WSLMS COs in conjunction with the FEG commanders and submitted without further consolidation so, we moved the WSLMS under DGLogOps and in turn I met with the Air Commander (by this time AVM Peter Nicholson) to seek his agreement to reviewing the bids from all of the FEGS and determining the order of funding particularly for those near or below the cut off line. Thus, the person responsible for the full spectrum of operational capability determined what would not be done when funding was limited. Most of the Commanders and COs accepted that this gave them far greater control although there was some pushback; but, most importantly HQLC staff officers were relieved of this responsibility which allowed them to get on with the job of procurement without the pressure of prioritising this.

I continued to fly the Vampire from Laverton and, when the closure of the airfield became imminent, we moved the Vampire to Point Cook. In fact, the Vampire was the last aircraft to fly out of Laverton and we only just made that as, out of the blue, truckloads of dirt started to be heaped on the 05 runway and I had to wait for a headwind on 05 and then accelerate past the dirt heaps by sticking to the RH side of the runway for the initial ground roll. This was now over 20 years ago on 11Feb1997. Operation of the Vampire from Point Cook on runway 17 was as safe (or unsafe) as Laverton with adequate runway length; but, of course, there were the interminable few seconds after take off at 110K to get above 160k when an ejection became possible and then 225K before a turnback onto runway 22 could be safely accomplished in the event of an engine failure. When we had the crash barrier at Laverton the window was narrower, as the barrier could be engaged by a planned land back usually up to around 125K-130K, depending on the wind; but, without the barrier, a controlled crash ahead was the only option from after take off up to 160K. Given that the cockpit of the Vampire is substantially wood forward of the firewall, in the event of such a landing into the rough there was not a lot of protection from forward impact. Also, as 23 was the usual runway at Laverton any turn back had to be onto 35 which was quite a short runway, with the Geelong railway power lines on the threshold reducing further the available runway in the event of a turn back.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Point Cook today. |

||

|

Early in the LogOps posting, the AOC (AVM Tom O'Brien) suggested that I should visit the staff members who were scattered throughout the US and ensure that all was OK. This turned out to be quite a major task and Tom also suggested that I take Carolyn along (at my expense of course) so that she could meet with the wives in the various locations to hear how they were all coping. We also needed to pursue a number of accounting aspects with the US Foreign Military Sales (FMS) hierarchy; so, I decided to take SqnLdr Mark Leatham, a Supply officer, with me. Carolyn decided that she would like to get a good set of golf clubs in the US so elected to travel economy (which she later regretted when Qantas sat her in the row forward of the promised emergency exit rather than the emergency exit and next to a very large male who spilled into her seat and badly needed a wash) and use the difference on golf clubs. Mark, with his broad background, proved to be an excellent choice and we chose to drive, where possible. The other main aspect that I needed to address was the future supportability of the F111, as we became the only operator in the world and the US was closing facilities such as the Cold Proof Load Test (CPLT) facility at Sacramento.

Accordingly, we flew into LA on a Friday (as Qantas didn't operate into San Francisco at the time) and then drove to Sacramento where we met with the commanding General, initially at a BBQ at his place on the Sunday. This was most valuable as it became obvious that the CPLT was to be demolished and we would have to make our own arrangements, if the F111 was to remain in service as the only other such facility in the world at Filton in the UK had also been decommissioned. The importance of a CPLT facility was, in simple terms, that at regular intervals the F111 needed to be inserted into the facility (basically a deep freezer large enough to fit an F111), frozen to around -43degC and then loaded to max flight load and, if nothing broke, structurally cleared for flight for a further few years. It was a little more sophisticated than this; but, not much – see HERE.

From Sacramento, we flew to Dayton primarily to meet with students at USAFIT (Institute of Technology) and we then drove, over the weekend, to Philadelphia to meet with the USN Supply organisation, where we had representatives principally associated with P3C Orion support. We then drove to Washington DC to meet with our people supporting US aircraft and from there over the following weekend to Jacksonville in Florida for more USN P3 interface. From Jacksonville we drove to Atlanta for C130 pursuits with Lockheed Martin and then flew to San Antonio and drove to Fort Worth for detailed F111 discussions. From Fort Worth we flew to Denver where the US FMS accounting personnel were based (COL Jack Harris and Lynn from Woomera/Nurrungar times drove up to Denver for a 'catch up') and we then drove, again over a long weekend from Denver, over the Rockies, to San Diego (overnighting in Las Vegas), to meet with our people building up the F18 support interface. Finally we drove up to LA for the flight back to Australia. Although nearly a month, this was a most valuable trip to scope what our overseas staffs were doing, meet with high level US military and contractor people to get up to date high level information on future developments and support and to build rapport with our people, some of whom were operating in considerable isolation, this being on the cusp of the internet and the explosion in rapid email communication and video tele conversations.

This trip also proved invaluable when we shortly after addressed future F111 supportability ie were there any insurmountable impediments to longer term F111 retention out to 2020 (this being 1996). This study brought input from many involved parties and essentially concluded that while we needed to build a CPLT facility, establish a production facility for the explosives used in the F111 cockpit capsule separation (the F111 did not have ejection seats. In the event of an emergency requiring airborne crew escape the whole cockpit separated intact and the crew remained in this capsule as it was parachuted to earth) and address spares acquisition and funding, there appeared to be no insurmountable impediment to retention. One innovation that we put into early effect was to try to capture USAF spares as they were disposed of by acquiring anything that might be of use at the disposal price of a few $ per pound weight and storing what was acquired in the US for evaluation when our F111's future was decided. This prevented key components (including, for example engines) being lost forever while basically costing only storage costs as anything subsequently determined as being unusable could be disposed of for about the acquisition cost ie the scrap value in $ per pound weight.

|

||

|

|

||

|

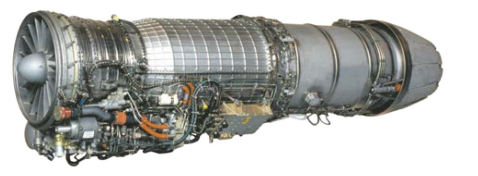

Another major activity was with the GE F404 engine in the F18. Short notice reduction in the lives of some components meant that we had insufficient engines available to maintain even a minimum online availability. Along with an Aerospace Research Laboratory (ARL) expert and two RAAF propulsion experts, at short notice I visited GE at Lynn, Mass to try to get to the bottom of the problem. Put simply there was no simple solution; but, the Canadians had, at the time, mothballed a number of F18's with the same engine. So, I then went to Washington to ascertain, if the Canadians agreed, that if we could 'borrow' a number of engines that there were no US impediments to us effecting this. Needless to say there were, including that the engines could not be shipped through the US. So, we approached the Canadians and I got 'in principle' agreement to such a loan and we eventually had the engines flown by RAAF C130s from Canada to Australia without entering the US. Needless to say, this summary makes it all sound easy!!

By this time I had been at HQLC for more than two years and started to get the vibes that, if I wasn't promoted by the end of 1997, then I may be looking to retire. RAAF was again going through another iteration of enforced (voluntary) early retirements. This was May1997 when, out of the blue, I received a call from AVM(Ret) Alan Heggen who I had worked closely with at Defair on various occasions. Alan was the Director of the Office of Australian War Graves and he enquired as to my interest in applying for his job as he was considering retiring. So, in early Jun 1997, I found myself having an interview in Canberra with the Minister for Veterans Affairs and his Departmental Secretary for that job. However, very shortly after Alan's call, I received a call from the Rolls-Royce Regional Director in Singapore who indicated that RR were looking to upgrade their Defence presence in Australasia but, had an open mind on how and was I considering retiring from the RAAF and, if so, would I be interested in discussing a position with RR (this approach was in no way connected with the previous approach by RR in 1985; but, it soon became apparent that RR had already researched me and a number of people subsequently let me know that they had received informal enquiries checking me out and this again confirmed how many senior appointments are really made).

|

||

|

|

||

|

Shortly after this, he contacted me again to ascertain my interest in meeting with the RR seniors from the UK and USA who would all be at the upcoming Paris Airshow and, on a no obligation basis from either side, see if we could determine if there was mutual interest. So, shortly after my Canberra interview, I flew to Paris, had a number of informal sessions with a wide range of RR people from the Chairman, Sir Ralph Robins, down and at the end of the week was made a very attractive offer. So, without committing, I flew home, discussed the options with the family, asked the RAAF if they could give me an indication of future RAAF intentions (which no-one could), withdrew my War Graves application and accepted the RR offer, subject to DoD agreement that I had no conflicts of interest. Fortunately, I had had very little to do with RR as DGLogOps so obtained this clearance and commenced separation from the RAAF, then in my 37th year of service.

Of course I had to give the requisite three months clear notice; but, managed to undertake an Aust Institute of Management Company Directors course as resettlement and finished up with a few days in an office in Russell to complete outstanding Officer Evaluation Reports and separate from the RAAF at Russell.

|

||

|

|

||

|

During this latter time, I was visited by an officer from the Inspector Generals Division who informed me that a whistleblower had anonymously complained that I, with Carolyn, had attended the Paris Airshow with all expenses paid by a contractor. Within LogOps we had had a number of similar vexatious accusations against various people all of which, following sometimes extensive investigation, had proven to be within the guidelines. While the guidelines were detailed and extensive, I found the simple statement by Sen Robert Ray when he was Defence Minister best summarised the position 'so long as you only eat, drink and smoke, take nothing away and no transport, especially airfares are involved, it is probably OK'. This was the first accusation against me; so, I started by pointing out that yes I had been to Paris, it was a job interview for a job that I had accepted, I was on leave and Carolyn certainly wasn't involved'. He responded that they had already confirmed that Carolyn had not left the country!! He then requested some confirmation that I was on leave; so, with him in tow, we headed for the RAAF Support Unit to check my leave card. As it happened, my departure for Paris had been at short notice and from Canberra; so, I had rung my Secretary, Maxine, at Laverton to lodge a leave application for me and had informed the AOC (then AVM Mac Weller) that I was travelling overseas on leave. It then struck me on the way to the Support Unit, what if the leave application hadn't been processed? However, the leave card proved that I was on leave and I heard nothing further. So it was that I separated from the RAAF on Fri 3Oct1997, had the weekend off unemployed, for the first time since I was 17, and started with Rolls-Royce plc on Monday the 6th Oct, 1997.

In the final instalment, Ian Ashbrook will cover his second career as a senior executive in the prestigious company Rolls-Royce plc as Regional Director (Defence) - Australasia and as an Executive Director of Rolls-Royce Australia Ltd and a director of the associated regional Rolls-Royce companies.

|

||

|

If you have a gun you can rob a bank, but if you have a bank you can rob everyone. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|