|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

Airman Aircrew.

Over the two days, 19th and 20th October, 2018, the RAAF Airman Aircrew Association blokes and blokettes got together at the Club Services Ipswich club rooms for one of their famous get togethers.

This page contains several HD photos and will take a few seconds to load.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

The “get-together” was organized by Howdie and Ruthie Farrar below.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Others at the reunion were:

|

||

|

|

||

|

Bob Pearman, Al Harris.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Barry Bircham, Paddy Sinclair.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Bill DeBoer, Max Lollback.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Sandra DeBoer.

Sandra was in the coffee section - someone has to drive home!!

|

||

|

|

||

|

Brittany and Rick Haslewood.

Brittany was one of the lovely young ladies who looked after everyone during the night.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Cheryl Coyne, Nola Luyton.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Chris Fernande, Bill Luyton, Steve Hennessy, Tony Hall.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Claire and Richard Haslewood.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Chris Fernandez, Bill Luyton.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Colleen Praniess, Richard Horne.

|

||

|

|

||

|

John Ridout, Tom Mills.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ian Lane, “Rossy”, Colleen Praniess.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kevin Dransfield, Frances Birchman

|

||

|

|

||

|

Colleen Praniess, Trev Benneworth

|

||

|

|

||

|

Lance Hazelwood, Bob Wheeler.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ted Crawley, Bryan Carpenter, Ruthie Farrar, Leonie Avery

Both Ruthie and Leonie were “hosties” on the Boeing 707 with 33 Sqn at Richmond.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kevin Dransfield, Rick Haslewood.

|

||

|

|

||

|

“Bronco and the Colonel”.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Richard and Jenny Horne.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

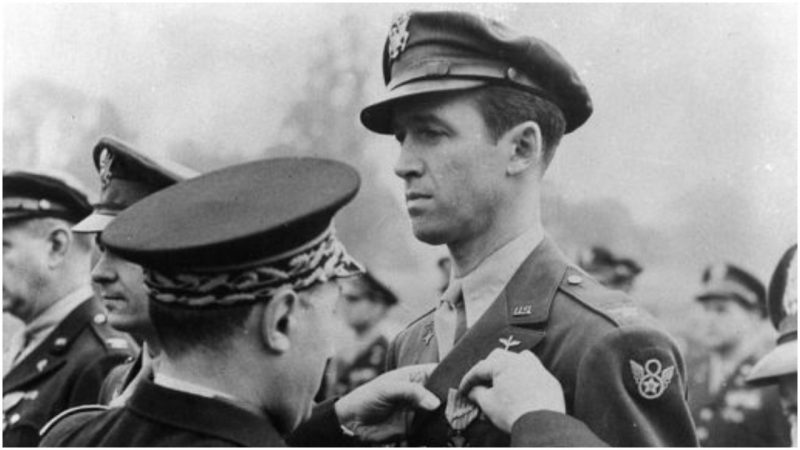

Jimmy Stewart.

Jimmy Stewart's family on both sides had deep military roots, as both grandfathers had fought in the Civil War and his father had served during both the Spanish–American War and World War I. Stewart considered his father to be the biggest influence on his life, so it was not surprising that, when another war came, he too was willing to serve. Members of his family had previously been in the infantry, but Stewart chose to become a flier.

An early interest in flying led Stewart to gain his private pilot certificate in 1935 and commercial pilot license in 1938. He often flew cross-country to visit his parents in Pennsylvania, navigating by the railroad tracks. Nearly two years before the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, Stewart had accumulated over 400 hours of flying time.

Considered a highly proficient pilot, he entered a cross-country race as a co-pilot in 1939. Stewart, along with musician/composer Hoagy Carmichael, saw the need for trained war pilots, and joined with other Hollywood celebrities to invest in Thunderbird Field, a pilot-training school built and operated by Southwest Airways in Glendale, Arizona. This airfield became part of the United States Army Air Forces training establishment and trained more than 10,000 pilots during World War II.

In October 1940, Stewart was drafted into the United States Army but was rejected for failing to meet the weight requirements for his height for new recruits—Stewart was 2.3 kg under the standard. To get up to 65 kg, he sought out the help of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's muscle man and trainer Don Loomis, who was noted for his ability to help people gain or lose weight in his studio gymnasium. Stewart subsequently attempted to enlist in the Air Corps, but still came in underweight, although he persuaded the enlistment officer to run new tests, this time passing the weigh-in with the result that Stewart enlisted and was inducted in the Army on March 22, 1941.

Stewart enlisted as a private but applied for an Air Corps commission and Service Pilot rating as both a college graduate and a licensed commercial pilot. Soon to be 33, he was almost six years beyond the maximum age restriction for Aviation Cadet training, the normal path of commissioning for pilots, navigators and bombardiers. The now-obsolete auxiliary pilot ratings (Glider Pilot, Liaison Pilot and Service Pilot) differed from the Aviation Cadet Program in that a higher maximum age limit and corrected vision were allowed upon initial entry. Stewart received his commission as a second lieutenant on January 1, 1942 shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, while a corporal at Moffett Field, California. He received his Service Pilot rating at that time, under the Service Pilot program established in March 1942 for experienced former civilian pilots. Although Service Pilots were normally restricted to noncombat flying, they were permitted to fly overseas on cargo and utility transports, typically with Air Transport, Ferry or Troop Carrier Commands. Under the regulations of the period, a Service Pilot could obtain an unrestricted Pilot rating after one year of USAAF service on flying status, provided he met certain flight experience requirements and passed an evaluation board, and some did in fact go on to combat flying assignments. Stewart's first assignment was an appearance at a March of Dimes rally in Washington, D.C., but Stewart wanted assignment to an operational unit rather than serving as a recruiting symbol. He applied for and was granted advanced training on multi-engine aircraft and was posted to nearby Mather Field to instruct in both single- and twin-engine aircraft.

Stewart had been concerned that his expertise and celebrity status would relegate him to instructor duties "behind the lines" and his fears were confirmed when he was used in training bombardiers. He was eventually transferred to Hobbs Army Airfield in New Mexico, for three months of transition training in the four-engine B-17 Flying Fortress, then sent to the Combat Crew Processing Centre in Salt Lake City, where he expected to be assigned to a combat unit. Instead, he was assigned in early 1943 to an operational training unit as an instructor. He was promoted to captain on July 9, 1943 and appointed a squadron commander. To Stewart, now 35, combat duty seemed far away and unreachable, and he had no clear plans for the future. However, a rumour that Stewart would be taken off flying status and assigned to making training films or selling bonds called for immediate action, because what he dreaded most was "the hope-shattering spectre of a dead end". He appealed to his commander who understood his situation and recommended Stewart to the commander of the 445th Bombardment Group, a B-24 Liberator unit that had just completed initial training at Gowen Field and gone on to final training in Iowa.

In August 1943, Stewart was assigned to the 445th Bomb Group as operations officer of the 703d Bombardment Squadron, but after three weeks became its commander. On October 12, 1943, judged ready to go overseas, the 445th Bomb Group staged to RAF Tibenham, Norfolk, England. After several weeks of training missions, in which Stewart flew with most of his combat crews, the group flew its first combat mission on December 13, 1943, to bomb the U-boat facilities at Kiel, Germany, followed three days later by a mission to Bremen. Stewart led the high squadron of the group formation on the first mission, and the entire group on the second. Following a mission to Ludwigshafen, Germany, on January 7, 1944, Stewart was promoted to major and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for actions as deputy commander of the 2nd Combat Bombardment Wing on the first day of "Big Week" operations in February.

On March 22, 1944, Stewart flew his 12th combat mission, leading the 2nd Bomb Wing in an attack on Berlin. On March 30, 1944, he was sent to RAF Old Buckenham to become group operations officer of the 453rd Bombardment Group, a new B-24 unit that had just lost both its commander and operations officer on missions. To inspire the unit, Stewart flew as command pilot in the lead B-24 on several missions deep into Nazi-occupied Europe. As a staff officer, he was assigned to the 453rd "for the duration" and thus not subject to a quota of missions of a combat tour. He nevertheless assigned himself as a combat crewman on the group's missions until his promotion to lieutenant colonel on June 3 and reassignment on July 1, 1944, to the 2nd Bomb Wing, assigned as executive officer to Brigadier General Edward J. Timberlake. His official tally of mission credits while assigned to the 445th and 453rd Bomb Groups was 20 sorties.

He continued to go on missions uncredited, flying with the pathfinder squadron of the 389th Bombardment Group, with his two former groups and with groups of the 20th Combat Bomb Wing. He received a second award of the Distinguished Flying Cross for actions in combat and was awarded the French Croix de Guerre. He also was awarded the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters.

|

||

|

|

||

|

He served in a number of staff positions in the 2nd and 20th Bomb Wings between July 1944 and the end of the war in Europe and was promoted to full colonel on March 29, 1945. Less than two months later, on May 10, he succeeded to command briefly the 2nd Bomb Wing, a position he held until June 15, 1945.

Jimmy Stewart was one of the few Americans to ever rise from private to colonel in only four years during the Second World War.

At the beginning of June 1945, he was the presiding officer of the court-martial of a pilot and navigator who were charged with dereliction of duty for having accidentally bombed the Swiss city of Zurich the previous March—the first instance of U.S. personnel being tried for an attack on a neutral country. The court acquitted the defendants.

Stewart returned to the United States aboard RMS Queen Elizabeth, arriving in New York City on 31 August 1945 and continued to play a role in the Army Air Forces Reserve following World War II and the new United States Air Force Reserve after the official establishment of the Air Force as an independent service in 1947.

He received permanent promotion to colonel in 1953 and served as Air Force Reserve commander of Dobbins Air Force Base, Georgia, the present day Dobbins Air Reserve Base. He was also one of the 12 founders and a charter member of the Air Force Association in October 1945. Stewart rarely spoke about his wartime service, but did appear in January 1974 in an episode of the TV series The World At War, "Whirlwind: Bombing Germany (September 1939 – April 1944)", commenting on the disastrous mission of October 14, 1943, against Schweinfurt, Germany. At his request, he was identified only as "James Stewart, Squadron Commander" in the documentary. (You can see that episode HERE).

On July 23, 1959, he was promoted to brigadier general. During his active duty periods, he remained current as a pilot of Convair B-36 Peacemaker, Boeing B-47 Stratojet and Boeing B-52 Stratofortress intercontinental bombers of the Strategic Air Command. On February 20, 1966, Brigadier General Stewart flew as a non-duty observer in a B-52 on an Arc Light bombing mission during the Vietnam War. He refused the release of any publicity regarding his participation, as he did not want it treated as a stunt, but as part of his job as an officer in the Air Force Reserve.

Stewart, however, often did his part in publicizing and promoting military service in general and the United States Air Force in particular. In 1963, for example, as part of the plot in an episode of the popular television sitcom My Three Sons, Stewart appeared as himself in his brigadier-general's uniform to address high-school students about the importance of science in society and about the many accomplishments of the select group of so-called "eggheads" being educated at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Five years later, after 27 years of service, Stewart officially retired from the Air Force on May 31, 1968. He received a number of awards during his military service and upon his retirement was also awarded the United States Air Force Distinguished Service Medal. On May 23, 1985, President Ronald Reagan awarded Stewart the Presidential Medal of Freedom and promoted him to Major General on the Retired List.

|

||

|

|

||

|

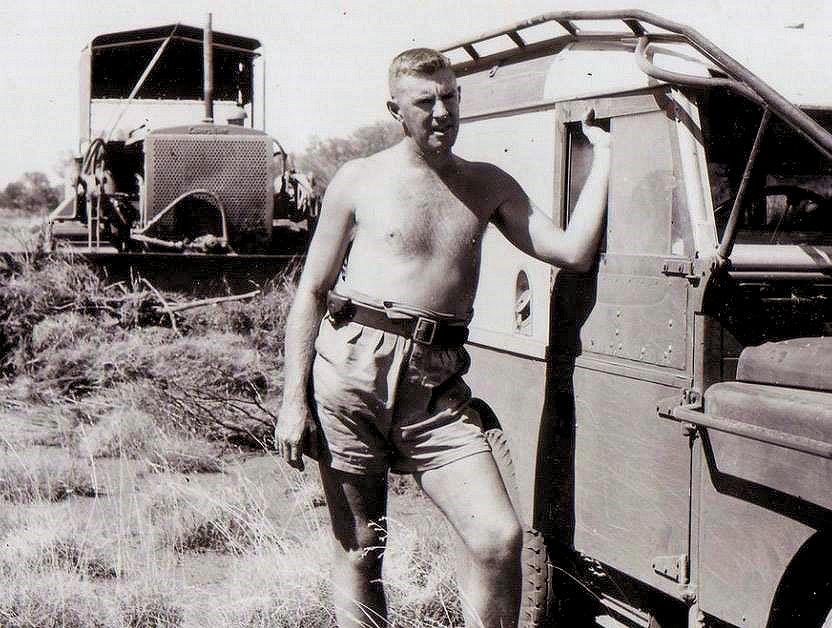

A Forgotten Australian Legend – Len Beadell.

Never heard of Len Beadell? Then you have never heard of the surveyor and road builder who, with a team of eight dedicated assistants (basically bulldozer drivers, mechanics and a cook), in the 1940s and 1950s built more than 6,500 kilometres of roads which opened up the Australian outback.

It was Beadell who headed the “gunbarrel crew” which built that extraordinary track, the Gunbarrel Highway, from Victory Downs (just west of the Stuart Highway on the South Australia-Northern Territory border) across to Carnegie in Western Australia. It was also Beadell and his crew who constructed the Anne Beadell Highway (these were access roads across sand dunes and deserts rather than sealed highways) from Mabel Creek Station (west of Coober Pedy) across to Laverton.

Beadell was proud of his work and he left small aluminium plates along the way to ensure that the drivers who followed didn’t get lost. Each plate was stamped with the latitude and longitude and, frighteningly, the distance to the next waterhole or station.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The actual construction makes fascinating reading: “The typical modus operandi was for Beadell to carry out forward reconnaissance in his Land-Rover by himself, and, on the basis of this, decide the best route for the road. He would then return to the rest of the group from which the bulldozer would lead off first with its driver guided by Beadell flashing a mirror (sometimes a flare was used) from the top of the Rover. The rough track was then smoothed with an ordinary road grader.”

Remarkably the roads are still there nearly seventy years later and they still present a challenge to adventurous 4WD enthusiasts wanting to cross Australia’s Dead Heart.

It is entirely appropriate that one rocky outcrop in the middle of nowhere, along the Gunbarrel Highway, is named Mount Beadell. On it is a memorial which tells the story of this remarkable man.

“Len Beadell (1923-1995) was born on a farm in West Pennant Hills (now a suburb of Sydney). After taking an interest in surveying at the age of 12, under the guidance of his surveyor-Scout master, he began a career with him on the military mapping program of northern NSW in the early stages of the Second World War. A year later he enlisted in the Australian Army Survey Corps serving in New Guinea until 1945. “While still in the army he accompanied the first combined scientific expedition of the CSIRO into the Alligator River country of Arnhem Land carrying out astronomical observations fixing locations of their new discoveries.

“Waiving his discharge for yet another term he readily agreed to carry out the initial survey for a rocket range later to be named Woomera. This decision led to a lifetime association with that project as a civilian till his retirement in 1988.

“After 41 years including continual camping, surveying, exploring and road making – he opened up for the first time in history over 2.5 million kilometres of the Great Sandy, Gibson and Great Victoria deserts. “He discovered the site for the succeeding Atomic test at Maralinga also laying out all the instruments needed to record the results.

“In 1958 as range Reconnaissance Officer at the Weapons research establishment he was awarded the British Empire Medal for his work in building the famous Gun Barrel Highway, the first and still the only 1500 km link east-west across the centre of Australia.

|

||

|

|

||

|

“Since then he has surveyed over 6,000 km of lonely roads in the deserts for access in establishing instrumentation for the Woomera and Maralinga trials.”

Beadell wrote a number of books, amusingly most of them have “bush’ in the title, (Beating About the Bush, Still in the Bush, Too Long in the Bush, Blast the Bush, Bush Bashers) rich in anecdotes and stories about his adventures and they are still in print.

There is also an excellent account of his life, complete with lots of photos and a map of all the roads he built, titled Len Beadell’s Legacy by Ian Bayly.

Len was a very funny man - listen to his talk to a Rotary function at Shepparton back on 1991. Click HERE.

|

||

|

Spackman Track.

Another well used track, named after a regular outback "bush-bashing" family.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Jezza, Geoff, Matt, Dave and Dan Spackman.

Over the years, the Spackman family have done many successful trips into the outback, some from east to west, some west to east, some north to south. The Spackman Track leads from the Anne Beadell Highway to Lake Rason in Western Australia. It is a nice easy two wheel sandy track suitable for 4 wheel drive vehicles only.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

.jpg)