|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

My Story.

|

||

|

Peter Condon.

I started my flying career as a cadet in the Air Training Corps (ATC) in Adelaide in late 1961. I had been awarded an ATC flying scholarship and started flying De Havilland Chipmunk aircraft at the Royal Aero Club of South Australia, passing my Private Pilot Licence test in March 1962 when I was still sixteen. The scholarship then provided four hours of flying each month at the Aero Club until I reached the age of eighteen and joined the RAAF’s No. 52 Pilot Course in late 1963.

I had flown about 130 hours before I started flying at Point Cook in Victoria and this experience gave me a good kick-start. After completing the basic flying training on the Winjeel at Point Cook, No. 52 Pilot Course moved to Pearce in late 1964 for advanced flying training on the Vampire. I can assure you that it was a wonderful experience to fly the Vampire after the piston-powered, propeller-driven Winjeel. On the first take-off, I can still recall the experience as the little jet accelerated into the sky after take-off; all quiet until the air-conditioned air was turned on and we zoomed towards the training area. No propeller out the front either—just the jet engine behind the cockpit whirring at about 10,600 RPM.

The course graduated in March 1965 and following is a photograph of the graduates so readers can have a bit of a chuckle over the changes in appearance of those they know, changed caused by (perhaps?) some nerve-wracking careers.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Standing L-R: Mac Cottrell, John Foran, John Harrison, Dick Cooper, John Lanning, Peter Condon, Peter Hay. Seated L-R : Peter Spurgin, Alby Fyfe, Ian McIntyre, Peter McNair, Bob O’Hanlon.

|

||

|

I was posted from 1AFTS to 2(F)OCU at Williamtown to fly the Avon Sabre, with my first Sabre flight three days before my 20th birthday. Conversion ride number ten, three days after my birthday, included the Mach 1.0 run so I was almost a supersonic teenager. The RAAF did not have two-seat Sabres so on my first flight I was all alone. We did have simulator training beforehand which was quite realistic and a taxi ride around the airfield with an instructor standing on the wing near the cockpit to hit me over the head if I did something wrong. I remember the nose-wheel steering was very sensitive (or sloppy) so the instructors needed a good grip on the side of the cockpit to avoid being flicked from their post.

Conversion flight number ten, where we broke the sound barrier, would be interesting to the fighter pilots of today. We climbed to 48,000 feet, which took some time, maintained climb power and rolled in and pointed the nose vertically down. If the aircraft was slightly out of aileron trim and it wanted to roll during the vertical acceleration, then we let it roll. Any aileron deflection would have added to the overall aircraft drag which may have prevented the aircraft from reaching Mach 1.0.

I broke the sound barrier that day.

|

||

|

2(F)OCU Sabre Course:

|

||

|

|

||

|

L-R: Brian Fooks, Peter Spurgin, Roger Wilson, Kevin Foster, Peter Condon, Mac Cottrell.

|

||

|

After graduating from OCU in August 1965, I was posted to No. 76

Squadron at Williamtown, along with Brian Fooks and Mac Cottrell. Soon

after, we were all on a squadron detachment in Darwin which had been

operating for some time because of what was called the ‘Indonesian

Confrontation’ - this included Malaysia. 76 Squadron had a permanent

detachment of eight Sabre aircraft at Darwin for nearly the whole time I

flew Sabres. We

A tough life!

On one of our returns to Williamtown from Darwin, Brian Fooks, Mac Cottrell and I noticed that, in our absence, we had been ‘volunteered’ to undergo Forward Air Controller (FAC) training. It seems that no one else wanted to do the course and our names were submitted without us being consulted. So much for the power of a Pilot Officer, even though Brian was a Flying Officer! The course consisted of two weeks of lectures, mainly about Army operations, followed by one week controlling some Sabres and Vampires in the low flying area, from the comfort of a jeep. We had a large-scale map under perspex and a black grease pencil to plot tracks from well-defined features to a target in our vicinity, like a bridge. Basically, we told the fighter pilot to ‘hack’ at low level over the defined feature, steer a heading for so many seconds and to then ‘pop’ for a rocket, bomb or gun pass. We would pick them up in the ‘pop’ (climb) and describe the target type and location to them. This was in 1966 before the Winjeels were used for airborne FAC training.

|

||

|

A Sabre deployment to Darwin in 1966.

|

||

|

|

||

|

L-R: Charlie Philcox, Brian Fooks, John De Ruyter, Brian Dirou, Peter Condon, Mac Cottrell, Geoff Peterkin, Jack Smith, Dick Kelloway, Al Walsh.

|

||

|

I flew in an ‘End of 76 Squadron’ flypast on 15 July, 1966 and continued my Sabre career with ‘Transition Squadron’, a part of 2OCU. I had 303 hours flying time in the Sabre when I joined No. 7 Mirage Course at 2OCU and had my first Mirage flight on September 12th. Again, this conversion training was all done in the single-seat Mirage. The training included simulator training and the first flight was flown with the instructor flying in formation in another Mirage. It was interesting getting airborne and looking outside to find the wing was not in view unless I looked well to the rear. I also still remember my first approach and landing in the Mirage. The flight called for a quick flight to the training area before returning to the circuit via a pitch-out, approach and overshoot, then back out to initial for a second circuit, this time landing.

Well, I have to tell you that 200 knots on base leg and 180 knots on final approach is pretty fast compared to the Sabre’s approach speed of about 140 knots. After turning base on the first circuit I managed to get in one ‘S’ turn before I had to overshoot. Things moved soooo fast. I was pleased that we were briefed for an overshoot because I had no other option. The landing off the second approach must have been okay because I’m still here. I should point out that with experience the base and approach speeds were reduced a bit.

|

||

|

Every year it gets harder to make ends meet Ends like hands and feet!

|

||

|

No. 7 Mirage Course at 2(F)OCU in 1966.

|

||

|

|

||

|

On wing L-R: Peter Condon, Jim Treadwell, Reg Meissner, Tassie Carswell. Standing L-R: Bruce Searle, Andy Patten (USAF), Jake Newham (Later CAS), Ron Magrath, Hugh Collits, Duane Madden (USAF).

|

||

|

I was posted back to. 76 Squadron after the Mirage Course and a few months later I was posted to 75 Squadron before the squadron deployed to Malaysia in May 1967.

|

||

|

A PR photo before departure for Malaysia:

|

||

|

|

||

|

L-R: Errol Walker, Dick Waterfield, Peter Condon, Bryan Sweeney, Jim Flemming (C.O.), Dick Moore, Roger Lowery, Geoff Coleman, Allan Walsh.

|

||

|

We flew twenty aircraft to Butterworth, Malaysia, in four days, including two days rest in Darwin. We flew Williamtown—Townsville—Darwin on the first day, then Darwin—Juanda—Butterworth on the fourth day. I flew A3-24.

The operation was called “Fast Caravan” and squadron members of all ranks still gather for reunions every second year.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

23 Mirages (some spares) lined up at Williamtown on the morning of the departure for Butterworth, Malaysia. They all made it.

|

||

|

The tour in Malaysia was very interesting. We were all in a new environment with interesting tropical flying and life in a foreign country and the married members had servants to help them in the home—paradise eh? The squadron also started operations in Singapore, being based at the Tengah fighter airfield where the RAF had Javelins and Hawker Hunter fighter aircraft. A squadron of Lightnings arrived in Singapore soon after.

|

||

|

|

||

|

No. 75 Sqn in action soon after the arrival in Butterworth. A3-24 is behind A3-30. The Mirage III is still the prettiest fighter aircraft on the planet.

|

||

|

Much of the initial flying in Butterworth was in the Air Defence role with plenty of GCI controlled intercepts and Air Combat Tactics, and with Ground Attack flights being introduced in early 1968.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Air Defence Exercise (ADEX) time in RSAF Tengah in Singapore. A3-41 fitted with Matra 550 and AIM 9-B missiles.

|

||

|

Old age is when you know all the answers But no one bothers to ask you the questions

|

||

|

I was posted out of 75 Squadron back to 76 Squadron in early 1969, only to be posted to South Vietnam to be a Forward Air Controller in April. This operational posting to Vietnam as a FAC flying USAF aircraft in support of allied ground forces would be most interesting to your readers so I will describe it in more detail as I don’t think many people understand what we did in Vietnam.

The Forward Air Controller’s job was one of the most dangerous flying occupations in Vietnam. It involved flying slow light aircraft over enemy territory at low altitude for up to six hours in a day searching for the enemy and then directing pilots flying ground-attack aircraft onto those targets—the average FAC mission lasting just under three hours. Other FAC tasks included artillery adjustment, visual reconnaissance and assisting ground forces with navigation. During the war the USAF lost 224 FACs killed in action, which is about a 10% loss rate. 36 RAAF fighter pilots flew as FACs with the USAF in Vietnam between 1966 and 1971 and we had no losses; but Chris Langton was shot down in his OV-10 in February 1970 and was rescued.

|

||

|

Arrival at Bien Hoa in Vietnam.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Dick Kelloway, on the right, points to the Cessna O-1 rockets as Doug Riding, Peter Condon and Gary "Huck" Ennis pose for the camera.

|

||

|

Doug Riding, Huck Ennis and I arrived at Bien Hoa in late April of 1969

after completing some administration at RAAF Vung Tau a few days earli

We all flew to Phan Rang where the USAF FAC training school was located and we were billeted with the RAAF’s No. 2 Squadron personnel. After seven days and seventeen hours, Huck and I were checked out as Forward Air Controllers in the Cessna O-1 ‘Bird Dog’, one of the slowest aircraft in the world! It had a 213 hp Continental piston engine and a maximum level speed of 100 knots; but the usual cruise speed was around 70 knots. Its maximum ‘g’ limit was “pull until the door pops open.” Because of our fighter background we were ‘A’ class FACs which allowed us to control airstrikes in close proximity to friendly ground troops. These close encounters were known as ‘troops in contact’ situations and involved a lot of liaison with the troop leader on the ground.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A Cessna O-1 ‘Bird Dog’ fitted with four marking rockets. Photo by USAF FAC Gary Dikkers. The Bird Dog was developed from the Cessna 170.

|

||

|

Huck and I were assigned to the US 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta area south of Saigon. There was a vacant FAC position at Dong Tam (near My Tho) and another a bit further south at Bin Thuy (near Can Tho). We travelled from Bien Hoa in a USAF Caribou to Dong Tam, the home of the US 9th Division HQ, where we drew straws to see who was the lucky man to remain at Dong Tam with the 1st Brigade FAC team. I lost that draw too! Huck flew down to Bin Thuy to join the 2nd Brigade crew and Doug Riding moved to Lai Khe after his OV-10 conversion to support the 1st Brigade of the US 1st Infantry Division.

After a few rides in the back seat of the O-1 watching experienced FACs controlling some airstrikes I was placed in the front seat with an experienced FAC supervising me from the back seat as I controlled my first air strikes in anger. It was difficult getting used to operating three radios, all at the same time, especially when working with troops in contact. We controlled the fighters on UHF, we spoke with Brigade HQ on VHF and we spoke with the ground forces on FM. I was sent solo after seven days and ended up controlling 34 airstrikes and flying 75 hours in my first month as a FAC. The next month I controlled 35 airstrikes and logged 78 hours flying time. The pace was high compared to my 22 hours per month back in the squadron.

|

||

|

|

||

|

An O-1 revetment at Dong Tam. Sandbags for wheel chocks. Eight smoke rockets.

|

||

|

I controlled airstrikes on most days that I flew. These were mainly pre-planned strikes on targets identified by the army during some of their previous patrols. I knew the time the fighters would arrive in the target area so I would depart Dong Tam in time to find the target and make a few assessments about attack heading, position of any friendlies in the area, safe bail-out areas and the nearest diversion base for the fighters if anything should go wrong. Soon after, the fighters would check-in on the UHF radio and I would describe where I was holding relative to a well-defined ground feature. They got close to my position by flying to a TACAN radial and distance from Bien Hoa. After they made visual contact with me I would ask the fighter pilots what weapons they were carrying and then give them a detailed briefing of the target and how I planned to run the airstrike. For example, bombs and napalm were usually dropped before any 20mm strafing passes.

There was a general rule that FACs should not fly below 1,500 feet to remain safe from enemy ground fire. In the early days many FACs were shot down trying to win the war at low level all by themselves; hence the height rule. However, If low flying was necessary to complete the mission, especially when friendly ground forces were in serious trouble, then a FAC would do what was necessary to get the job done. After the weapons were expended the FAC would give the fighters a Bomb Damage Assessment (BDA) and they would depart the area while the FAC positioned himself for the next scheduled airstrike. Having two pre-planned airstrikes each day was common when I was with the 9th Division, and on a busy day, especially after ground forces called for assistance because they were engaged with the enemy, I controlled up to four flights of fighters. On one day I managed to log four hours and five minutes for the one mission, only to be told some time later that I exceeded some rule about flying time. It was the only mission where I intentionally ran one fuel tank dry and played around with the mixture control while using the other fuel tank.

|

||

|

It never worries me when I get a little lost. All I do is change where I’m going.

|

||

|

The most common fighter aircraft used for ground attack when I was in Vietnam was the USAF F-100 Super Sabre. These aircraft were based at various locations around Vietnam but the most common departure airfields for operations in my area were Bien Hoa and Phan Rang. The weapon load usually consisted of a mix of bombs and napalm and 20mm cannon. I controlled USAF Cessna A-37 attack aircraft, USAF F-4s and F-5s along with a few Australian Canberras, the ‘Magpies’. I even controlled a USN OV-10 which stumbled into the target area looking for somewhere to expend his Zuni rockets. The Vietnamese Air Force operated F-5s and piston-engined A-1 bombers (left) and they were very accurate in the ground attack role. Understanding the VNAF pilots, and them understanding me, was a bit of a problem so we had to run the briefing very carefully, emphasizing the important points. They had been doing the job since they were old enough to fly so I respected their skills. They were good.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A USAF F-100 drops napalm canisters on a low-level pass. USAF Photo.

|

||

|

Controlling fighters in troops-in-contact situations was very rewarding, especially if I managed to get the fighter ordnance on target and the enemy assault defeated. I ended up being very busy during these missions, listening to all three radios at the same time and liaising with the ground forces to mark their positions with coloured smoke. Once the friendly positions were identified I would roll in to mark the enemy positions with a White Phosphorus (WP) smoke rocket. I aimed the rocket by lining up a painted nut on the inside of the divided windscreen with the tip of a welding rod fitted to the nose of the aircraft.

On most occasions when I controlled airstrikes in close proximity to friendly ground forces, only the fighter’s 20mm cannons could be used because the friendlies were inside the safety distances of the bombs and napalm. On two occasions when controlling airstrikes in the Bird Dog I ran out of smoke rockets and had to mark the enemy position with beer can-sized white smoke grenades. The smoke grenades were carried behind the seat and had to be dropped by hand through the open cockpit window after the pin was pulled. I lined the aircraft up in a shallow dive towards the enemy position, and when overhead the enemy at about 200 feet, dropped the grenade. Descending so close to the enemy was a bit uncomfortable because I knew the aluminium engine cowling would not stop a pea shooter if someone wanted to have a go at me. I wanted to hide behind the engine but I could not lift my feet off the rudder pedals nor duck my head down low because I had to see where I was going. There I was, flying the slowest aircraft in the war, trying to hit the enemy on the head with a smoke grenade! The smoke bloomed soon after it was released. It was during these two low flying missions that I realized the Bird Dog did not climb very well on full power. It took forever to get away from the action on the ground.

In all, during my time flying the Bird Dog, I flew 13 missions supporting troops in close contact with the Viet Cong (VC) enemy. These missions usually involved controlling three flights of fighters. During one afternoon battle, I had to request a Dakota flare ship (Spooky) to illuminate the target area as the fight continued into the night. That was a different and difficult experience again.

In a bit over two months flying the Bird Dog I clocked up 210 flying hours and controlled 91 airstrikes. The US 9th Infantry Division was one of the first US Divisions to return to the USA so Huck and I were out of a job and sent back to Phan Rang to learn how to fly the new OV-10 twin-engined FAC aircraft. It carried 14 smoke rockets so I would never have to do a low-level grenade-dropping pass ever again.

|

||

|

Growing old is compulsory. Growing up is optional.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Dong Tam was a rocket and mortar target about every second night. If the ‘incoming’ siren sounded while we were having a few beers after flying, we FACs would move into our bunker adjacent to our hooch until we got the all clear. Here USAF Captain Joe Nuvolini poses behind a mortar/rocket crater. Our hooch is behind the truck in the background.

|

||

|

|

||

|

I took this photo from the backseat soon after I arrived at Dong Tam. Looking south, it shows the north arm of the Mekong River in the distance and four rocket tubes under the wing. On the ground we can see a bright white WP smoke just blooming alongside a burnt-out smoke rocket. The larger smoke blooms are the result of bombs hitting the target nearer to the canal.

Further to the right of the target area is a triangular shaped abandoned Vietnamese Army fort. We were probably around 1,500 feet high.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A direct hit with a 500lb bomb spreads the smoke.

|

||

|

The idea for the OV-10 was started by two US Marine officers. They saw the need for an aircraft that could operate from rough fields and be able to support troops on the ground with some fire power such as bombs and machine guns. They wanted it to be able to carry 2,000lbs of cargo or carry six paratroopers and have a short takeoff and landing capability. Two seats and good cockpit visibility were other requirements. The production aircraft was fitted with two 715 shp T-76 Garret turbine engines and two zero-zero ejection seats. In the FAC role it carried four seven-rocket canisters—two for WP and two for HE, and four M60 machine guns.

It had a 40 feet wingspan and its maximum speed at sea level was about 250 knots. Its take-off speed was around 100 knots and its red-line speed was 350 knots. The usual recon speed with the rocket pods was about 130 knots. The approach speed was 100 knots and it was aerobatic with a plus 6.5 ‘g’ limit. A joy to fly.

|

||

|

|

||

|

An OV-10 ‘Bronco’ with a centre-line fuel tank. Photo by USAF Captain Brad Wright.

|

||

|

|

||

|

An OV-10 before flight on steel matting at Di An. An improvement on the Dong Tam O-1 revetment.

|

||

|

At Phan Rang we were checked out in three days (eight flights) and sent back south to join the US 1st Infantry Division. Huck joined Doug Riding at Lai Khe and I joined the 2nd Brigade FAC team at Di An just to the north of Saigon. At Dong Tam and at Di An, the FAC teams consisted of about five FACs so we sometimes flew two sorties each day while covering the Area of Operations (AO) during daylight hours. The living quarters were quite basic in both places. I had a bed and a small table and chair in a long ‘hooch’ building, separated from the other FACs with a fixed partition and a metal locker. The shower and loo facilities were very primitive too.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Preflight inspection of the OV-10 armament. WP and HE rockets and M-60 machine guns. The guns were not loaded nor fitted to all Di An aircraft when I flew the OV-10.

|

||

|

I supported the 2nd Brigade of the US 1st Infantry Division, flying the OV-10, from late July to mid December 1969, ending my eight month posting to Vietnam. I logged 260 hours and controlled 48 airstrikes in the OV-10. I was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in September.

We had one OV-10 aircraft at Di An which is now of particular interest to all Australians because it is being restored for display by the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It will be the only USAF aircraft in the Memorial. Seven Australian FACs flew #639 while on duty in Vietnam and I managed to fly it on 41 missions before I returned to Australia.

You can check the history of the aircraft and see the restoration progress HERE. (Definitely worth a look). When the restoration is completed, it will probably be on display at the Mitchell Centre in Canberra unless we can convince the AWM Director to move “G for George” to make room in the main memorial building.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ron Slater and me with OV-10 No. 639 at Di An in September 1969. This aircraft is currently being restored by staff at the Australian War Memorial for display.

|

||

|

Living to 100 has one advantage – no peer pressure.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The OV-10 idea originated as a Counter Insurgency (COIN) aircraft by two Marine officers. Besides being easy to operate ‘in the field’, its cargo compartment was at truck-tray height and large enough to carry five parachutists (door removed). The engines could be easily changed in the field and would operate on truck fuel (diesel) in an emergency.

|

||

|

After Vietnam I returned to No. 76 Squadron flying Mirages again, however I did spend a month flying a Winjeel in the FAC role on an Army exercise at Rockhampton, logging 55 hours which included a refresher flight with Arthur Sibthorpe. In August 1970 I was posted to McDill AFB in Florida, USA to undergo training on the Phantom F-4E fighter which the RAAF was leasing until a problem with the F-111’s wing carry-through box was sorted out. The RAAF leased 24 F-4Es for about three years while waiting for the F-111s to arrive.

The F-4E was a very capable aircraft. It was a Mach 2.0 all-weather fighter which could carry an impressive load of bombs. At McDill I flew 35 hours which included general flying training, weapons training and air-to-air refuelling before moving on to the McDonnell Douglas factory in St Louis to pick up a brand new F-4E to fly home to Australia. That exercise took four flights and 22 hours—the longest hop being seven hours between Honolulu and Guam. The most refuellings were done on the 5.5 hour leg from George AFB near Los Angeles, to Honolulu. This was because there were no diversion airfields available so our fuel tanks were kept topped up around the midway point so we could make it back to George AFB if something went wrong. I think we had three top-ups in the space of about one hour.

I served my time on F-4Es in No. 1 Squadron at Amberley. Our main role was Air-to-Ground so we spent a lot of time on the Evans Head bombing range using all the different bombing methods and techniques the aircraft equipment offered. The F-4E was a two-crew aircraft so the ‘Guy In the Back’ (GIB) controlled all of the radar and navigation equipment used when operating on the weapons range or in the air intercept role. The F-4Es also did quite a few maritime strike missions against RAN targets and I recall the low flying training sorties we did over the sea to gradually step our height down to 50 feet above the water (I think it was 50 feet). The CO, Wing Commander Mike Ridgeway was the leader of the four-ship formation. The normal minimum height over the sea was 150 feet. On the subsequent strike against the RAN I can still recall seeing under the lip of the aircraft carrier deck as we whizzed past.

I flew about 680 hours in the F-4E.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Two RAAF Phantom F-4Es.

|

||

|

In the early days of F-4E operations at Amberley an F-4E had a hydraulic failure so the crew decided to make an approach-end barrier (hook wire) engagement. This was normal procedure but the barrier malfunctioned and the F-4E ended up on its belly on the grass adjacent to the runway.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The barrier system was bought for the F-111 fleet so had been sitting idle for some time before the engagement. Basically, one of the braking drums did not work correctly so the landing roll-out after engagement was all one sided. This accident lead to the need to service the system and conduct some trials using an F-4E with a hook to prove that it worked as designed. Jim Graham (GIB) and I were picked for the task and we conducted about 30 hook-wire engagements at various speeds before the ARDU trial was completed.

On 16 June, 1971 Jim Graham and I were on a night time navex to Evans Head bombing range to do some 30 degree Dive Toss passes when we received word that an aircraft ahead of us had crashed into the sea while in the bombing circuit. The crew were Squadron Leader Stu Fisher and Flight Lieutenant Bob Waring. Jim and I spent some time flying around the area listening and watching for any sign of life, but there was nothing. We returned to Amberley knowing we had lost two mates that night. When we were on GCA finals with about five miles to run to landing I started to shake. The shakes continued to landing.

In mid-1973 I was posted to Central Flying School to undergo Flying Instructor training. From there I was posted to 2FTS at RAAF Base Pearce in WA to instruct on the Macchi jet trainer. My first instructional flying was with No. 87 Pilot’s Course. While at Pearce I was promoted to Squadron Leader and became the ‘A’ Flight commander, and in 1975 Bruce Wood and I performed a synchronized aerobatics routine for some RAAF air displays around the country. Our routine included a line astern tail slide from the vertical position which was a bit different in those days. I had testicular cancer diagnosed about that time and I would receive radiotherapy in Perth in the mornings and practice our flying routine with Bruce in the afternoons. I underwent 20 radiotherapy sessions at the time, and because of the need to be reviewed by the Perth doctors, my Pearce posting was extended for a further year. My last pilot course was No. 97 Pilot’s Course. In January 1977 I was posted to Williamtown for a Mirage Refresher Course before my posting to No. 75 Squadron in Malaysia as the squadron Operations Officer. Life was good.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A Macchi during a formation flypast over the city of Perth.

|

||

|

Returning to Malaysia for my second tour was a wonderful surprise. The local scene had changed quite a bit since my first tour ten years beforehand. What was noticeable was the improved standard of living of the local people. In 1967 the streets were cluttered with bicycles and motor bikes but in 1977 they had graduated to motor bikes and cars. We also used the local restaurants much more than we did in 1967.

Squadron flying operations remained similar but the air-to-air and air-to-ground training was more even, utilizing the Song Song weapons range, WSD-42 (HE bombing range) and the air-to-air gunnery range over the Malacca Straights to the west of Butterworth. Detachments to RSAF Base Tengah in Singapore continued; the task being shared with 3 Squadron.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A Mirage taking off from runway 36 at Butterworth.

|

||

|

|

||

|

This photo was taken west of Penang Island on 13 December 1977. The fins were painted with the RAAF squadron colours by the two local squadrons, Nos 75 Sqn and 3 Sqn. From the leader, the fin colours represent the order in which the Mirage aircraft entered RAAF service.

No 1–ARDI–Nick Ford. No 2–2OCU–Peter Condon. No 3–75 Sqn–Mick Parer. No 4–76 Sqn–Jack Smith. No 5–3 Sqn–Bruce Grayson. No 6–77 Sqn–Neil Burlinson. Camera aircraft–A3-107–Brian Brown with photographer Dennis Hersey.

|

||

|

After my 75 Squadron OPSO posting I was posted to Canberra in 1980 to do the 12-month RAAF Staff College Course. I was caught! After graduating from Staff College I was posted to Air Force Office to be Operational Requirements–Fighter, taking over from Al Taylor. Al Taylor and Ray Conroy, the leader of the small team formed to select the Mirage replacement, had recommended the RAAF purchase the F/A-18 so my task was to help higher management progress that decision to the purchase being finalized. The other aircraft in contention was the F-16 but it did not have an all-weather intercept capability. Another task was to convince the higher committees that our F/A-18s needed HF radios to operate at long range over the sea, in conjunction with the Jindalee Over-The-Horizon-Radar. This was a touchy point because the RAN did not support this proposal because it felt that the aircraft carrier could and should handle the job and suggested that if the Hornets were ever tasked for such long-range missions then they could fly out towards the targets in 50-mile line astern, relaying commands through the formation back to the controller. The installation of HF radios in the Hornets was approved and the RAN carrier was decommissioned some time later.

I thought we were all on the same side!

|

||

|

|

||

|

RAAF Base Darwin in about 1983. RAAF Photo.

|

||

|

In late 1982 I was posted to Darwin as the temporary CO of Base Squadron for eight months before again undergoing Macchi and Mirage refresher training and proceeding to RAAF Butterworth to fly my old Mirage A3-24 back to Darwin, arriving on 11 August 1983. Ray Conroy (CO) led the Squadron back to Darwin and the next day I became the CO; my third posting to No. 75 Squadron in 16 years.

Squadron life in Darwin was good. The

supply of aircraft spares was quite slow initially as they were mainly

distributed from Williamtown and I’m sure the Williamtown people were

reluctant to dispatch the last of any item on their shelves. However,

the supply chain gradually improved and the

The old Leanyer weapons range just to the north of Darwin airfield that we used when I was flying Sabres had been decommissioned so the squadron had to deploy elsewhere to conduct air-to-ground weapons training. The Quail Island HE range just to the west of Darwin was also being decommissioned. The squadron deployed to Williamtown in February 1984 to use the Salt Ash weapons range and it deployed to Butterworth via Bali in August to participate in an ADEX and remain there to use the Song Song weapons range. In October we deployed to Learmonth via Port Hedland for some High Explosive bombing and to participate in an exercise with USAF F-16s. In February 1985 we again deployed to Williamtown for air-to-ground training on Saltash Range and followed up with a deployment to NAS Nowra for some Fleet Support work for two weeks.

In May 1984 the fleet was grounded for a month because of undercarriage extension failures. This grounding also resulted in the squadron missing out on a Darwin ‘Pitch Black’ exercise. More importantly, on 22 June 1984 I fired the RAAF’s last two AIM 9B Sidewinder missiles out to the west of Darwin. The target was a flare dropped from a RAAF Caribou aircraft.

On 27 May 1985 Flying Officer John Quaife ejected from Mirage A3-36 as he was turning on the base leg of the circuit just before landing. He had been the leader of a four-ship simulated strike exercise and I saw it all happen because I was his number two and behind him in the circuit. Basically, when he reduced power turning base the RPM reduced to idle and could not be increased (a stops-corrector malfunction). He had a few swings in his parachute before he landed in marshy land on the coast to the west of the airfield. The aircraft continued to fly without the pilot and did a rough bouncy landing in the shallow sea water. It was later dragged from the sea and taken to the airfield. 75 Squadron restored A3-36 in the squadron’s colours for static display in the Darwin Aviation Museum where I saw it about 16 years ago. More recently, it has again been restored to ‘new’ condition by 75 Squadron at Tindal and placed back on display.

|

||

|

|

||

|

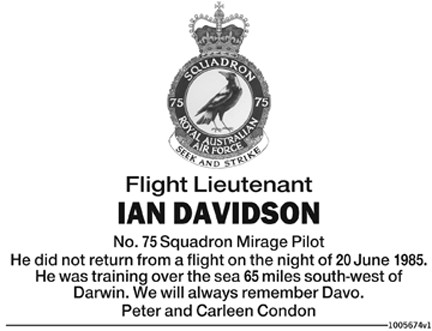

The last RAAF 9B Sidewinders: John Quaife, Peter Condon, Mark Pearsall, Peter Batten, Dave Halloran, Ian Davidson, Bernie Voysey, Paul Devine, Neil Burlinson, Bob Chaplin. I included this photo because it includes Flight Lieutenant Ian Davidson who was killed during a night intercept mission one year later.

|

||

|

On the 20th of June, 1985 we

lost Flight Lieutenant Ian Davidson during a night time intercept

training mission over the sea to the south-west of Darwin. I was flying

with Ian on that night. I was the target aircraft at 1,000 feet and Ian

was the fighter at a higher altitude. The mission was ‘Low level

Intercepts with Evasion’ and as we were zipping up our ‘g’ suits prior

to the flight Ian said that he was going to ‘get’ me. During his final

attack I noted that he did not respond to a couple of radio calls by his

controller so I called him too. He did not answer me so I asked the

controller to mark his las

The loss of Flight Lieutenant Ian Davidson on the night of 20 June 1985 still hurts.

I have placed this notice in the NT News on the 20th June each year since 1985.

My last Mirage flight was on 23rd August 1985. I had been posted back to Air Force office in Canberra to be the ‘Tindal Project Development Team’ leader. I was not very pleased about being posted out of Darwin in August as our three children were in school in Darwin, so I sought an extension until after the school year. This was not approved. Consequently, our eldest son was sent to a boarding school in Townsville, our youngest son remained in Darwin boarding with the Senior Naval Officer’s family, and our daughter went to Canberra with my wife and I. I was not a happy little Vegemite.

Besides operational needs, my position as Tindal Project Development Team leader was mainly to identify and promote infrastructure which would make life comfortable for families. Most of this had already been planned by the Director General of Air Force Works so there was not much to add to the plan. When the plan had been accepted I was being considered for a position in ‘Operations’ in Air Force Office so I visited the place and asked some questions about what went on there. I returned to my desk and wrote my resignation letter. My last day in the RAAF was on 19 June, 1986. I was 41 and I had served for almost 23 years.

After life in the RAAF I became involved in the Australian Coastwatch activities and returned to Darwin to join a company which had just been awarded a contract to conduct coastwatch operations around the northern coast of Australia. Cutting a long story short, the company failed to meet all contractual obligations so lost the contract. I then joined Lloyd Aviation as their Darwin manager for operations at Darwin and Troughton Island in support of the oil industry. The company operated both fixed and rotary winged aircraft.

After four years at Darwin I joined ‘Fleet Support’ flying Learjets out of Naval Air Station Nowra in NSW. The company had a Department of Defence contract to provide target towing services to the navy but this soon grew to include all sorts of support, including banner towing for the RAAF, GCI training, DSTO trials, Jindalee trials, and much more. The company had six Learjets and these flew all over the place providing support for the RAN, Army and RAAF. Deployments were made to Butterworth, New Zealand, Christmas Island, Cocos Island, RAAF Pearce, Indonesia, RAAF Darwin and all places in between. The contract later changed hands to ‘Pelair’ and I became the Learjet Check and Training pilot, mainly because of my instructional experience gained at RAAF Pearce many years before. Pelair operated four 35/36 model Learjets and two Westwind 24 twin jets and we all flew both types.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Learjet 36, VH-SLE on an early morning maritime strike mission 350 miles east of Darwin.

|

||

|

I retired from Pelair in January 2003 and worked on my next life adventure which was to buy a large 31-foot 5th Wheeler Caravan and a Chevrolet Silverado HD 2500 and check out the country from ground level. My wife and I did that for two years and then ‘retired’ again to the Gold Coast in 2005 and we have been here ever since.

After settling on the Gold Coast I spent quite a bit of time producing a few books. The first book was about the Learjet aircraft that I flew in Nowra, Flying the Classic Learjet. It was based on the training notes that I used to familiarize new pilots on the aircraft systems and operating procedures (check lists etc) so that they had something to take home for study.

After that book was self published, I

helped the FAC Association in the USA to produce a ‘coffee table’ book

which included the history of US Forward Air Controlling from the time

of the civil war until the end of the Vietnam war. Cleared Hot

included 232 real-

I’m now ‘booked out’ so don’t even ask.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Peter Condon, Huck Ennis and Brian Fooks viewing the restoration work on OV-10 639 at the Australian War Memorial in July 2018.

|

||

|

Age doesn’t always bring wisdom. A lot of time age turns up all by itself.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

squadron was able to operate at its planned rate of effort. Soon after

we arrived in Darwin I received permission from HQOC to take Wilf

Arthur, (right) a WWII commanding officer of the squadron in New Guinea,

for a ride in the two-seat Mirage. Wilf lived in Darwin and he and his

wife Lucille were honorary members of the Officers’ Mess. He enjoyed the

ride and his aircraft control was very smooth; he had not forgotten

anything. At age 24, Wilf was the youngest Group Captain in the history

of the RAAF.

squadron was able to operate at its planned rate of effort. Soon after

we arrived in Darwin I received permission from HQOC to take Wilf

Arthur, (right) a WWII commanding officer of the squadron in New Guinea,

for a ride in the two-seat Mirage. Wilf lived in Darwin and he and his

wife Lucille were honorary members of the Officers’ Mess. He enjoyed the

ride and his aircraft control was very smooth; he had not forgotten

anything. At age 24, Wilf was the youngest Group Captain in the history

of the RAAF.

t

seen radar position and alert all concerned. I climbed to about 3,000

feet and searched visually and listened for any sign of life. I recalled

doing this 14 years earlier—another mate gone. When my fuel was low I

returned to Darwin to land, and once again, on final approach I again

started to shake.

t

seen radar position and alert all concerned. I climbed to about 3,000

feet and searched visually and listened for any sign of life. I recalled

doing this 14 years earlier—another mate gone. When my fuel was low I

returned to Darwin to land, and once again, on final approach I again

started to shake.

life

stories submitted by USAF and allied pilots who participated in the

Vietnam war as FACs. I later produced Cleared Hot Book Two with a

similar number of stories; both books being over 500 pages. After that

effort I helped two more USAF authors produce books about their FAC

units’ experiences during the war, The Rustics and the Red

Markers. My last effort was producing Gallipoli-the first day

which explained, in simple terms, what went on over there on 25th

April, 1915. My wife and I were about to visit Gallipoli and having a

bit of an idea what went on 100 years earlier would help her to

orientate herself.

life

stories submitted by USAF and allied pilots who participated in the

Vietnam war as FACs. I later produced Cleared Hot Book Two with a

similar number of stories; both books being over 500 pages. After that

effort I helped two more USAF authors produce books about their FAC

units’ experiences during the war, The Rustics and the Red

Markers. My last effort was producing Gallipoli-the first day

which explained, in simple terms, what went on over there on 25th

April, 1915. My wife and I were about to visit Gallipoli and having a

bit of an idea what went on 100 years earlier would help her to

orientate herself.