|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

John Laming Aircraft and other stuff. |

||

|

|

||

|

The Pot Belly Stove.

The town of Sale in south-east Victoria can be damnably cold in winter. It was probably for this reason the nearby RAAF base at East Sale in 1955 seemed to have more pot-belly stoves per square mile than most other places in Australia. It was around the stove in “A” Flight hut at Central Flying School, that the characters in this story would gather to talk about the days flying and of adventures survived. Outside, cold sou’westerlies from over Bass Strait might howl between the hangars but inside the flight hut the pot-belly stove would give forth a radiant glow and the coffee smelt just fine.

|

||

|

|

||

|

After graduation from No 8 Post War Pilots Course in December 1952 I had

spent over two years in Townsville flying Lincolns, Wirraways, a Dakota

and a Mustang. From there I was posted to CFS to undergo a five month

flying instructors course. In those days one had to serve a minimum of

four years from graduation before being eligible to leave the service.

So, after selling my old Morris 8/40 Coupe to an air gunner for fifty

quid, I went by

I first learned to fly at the Kingsford Smith Flying School at Bankstown. My instructor for the first few trips was a Hungarian who had migrated to Australia after the war. He spoke with a heavy accent and as a result I learned very little. Another instructor was bored witless with his job and my flying suffered. The next instructor was Bill Burns an ex wartime Hudson pilot who happened to be the flight safety manager for Qantas and who kept current by instructing on Tiger Moths and Wackett trainers. Bill was wonderful and he sent me solo after eight hours.

I had lived alone since I was 17 years old and now the RAAF was my home. There was always this nagging insecurity that one day the RAAF might not renew my term of service and I would be out of a job. And so, while passing through Sydney I rang Bill Burns, who by now had climbed up the corporate ladder in Qantas and asked him about job prospects as a first officer with Qantas. Fortunately, he remembered the scruffy youngster who he had sent solo a couple of years earlier and kindly arranged an interview with himself and Captain Lowse – a senior Qantas captain. I recall little about that interview and as I was still in the RAAF 15 years later, I guess I didn’t make the grade. Of course, it could have been something to do with not being available for another two years, which is what I had left to serve.

Thursday 21st July 1955 and from Sydney, Loretto and I boarded a TAA Convair for Melbourne just in time to catch the last train to Sale. We froze on the train and after arriving at midnight, booked in at the run down Terminus Hotel. Motels did not exist in those days. The next day was gloomy, wet, and cold. We couldn’t afford more than one night in the pub – not on a sergeant’s pay packet anyway. There were no houses for rent in Sale and we weren’t entitled to a RAAF married quarter because my posting was not permanent. So, we hired a car and drove to Bairnsdale, a small town 45 miles to the east of Sale. Bairnsdale was a RAAF training base during the war operating Beauforts, Hudsons and Ansons on anti-submarine patrols over Bass Strait. There we pored over the local newspaper for rooms to rent and found a kindly old lady who had a spare room. It meant sharing the lounge but at least it was company for my wife. Meanwhile the only way we could get to East Sale from Bairnsdale was to hitch-hike. Loretto, an attractive young woman of 22, could show a mean leg - her charm guaranteeing us a lift within minutes of hitting the open road. Each day for the first two weeks before the instructors course began, I would leave her at the main township of Sale where she would window shop and look for accommodation. I then walked or hitch-hiked the two miles from the town to the RAAF base at East Sale aerodrome and pick up study books and arrange my own accommodation at the Sergeants Mess. In the late afternoon we would hitch-hike back to Bairnsdale.

|

||

|

|

||

|

On the 29th July I wandered into the School of Air Navigation which was 50 yards away from the CFS flight huts. It was another bitterly cold day and as always the resident pot-belly stove glowed warm and cheerful. On the flight line were several Lincoln bombers used by the school for long range navigation – plus an assortment of Wirraways, Mustangs, Vampires and half a dozen Dakotas. Tucked away safely away from the howling wind were a dozen Tiger Moths behind closed hangar doors.

The flight commander at SAN was Squadron Leader Rex Davie DFC & Bar – a former Lancaster pilot. Rex was a cheerful friendly man and I liked him immediately. When he heard that I had flown Lincolns, he asked me if I could help him out with a crewing problem that had just surfaced. A 10 hour night navigation exercise to Oodnadatta was about to be cancelled because SAN were one pilot short to fly the Lincoln. Would I do the trip? You betcha life I would, Sir, was my reply. I told him that I had never flown in command of a short nose Lincoln Mk 30 – only the long nose Mk 31version. That didn’t worry Rex Davie, as he knew that the long nose Lincoln was a difficult aircraft to handle at night - making the short nose version a doddle.

The rest of the crew consisted of a navigation instructor, two trainee navigators, two signallers and a co-pilot called Flight Sergeant Smyth. Despite being rugged up in a woolly bull flying suit, it was bitterly cold at 16,000 ft and we wore oxygen masks all the way. The weather had closed in at East Sale while we were gone and on our return GCA gave us a radar controlled final approach in low clouds and gusty winds. At least I could see over the nose of the Mk 30 once we broke out of cloud at 500 feet, which is more than can be said of the Long Nose Lincoln where lack of forward vision made cross-wind landings at night rather hairy. Arriving back at 0300, I snatched a few hours sleep before breakfast, then hitch-hiked the 45 miles back to Bairnsdale.

While Loretto tramped the streets of Sale looking for rooms to rent and put up with the food at various greasy spoon cafes, I enjoyed roast beef and yorkshire puddings at the Sergeants Mess, as well as flying each day in a Wirraway, Tiger Moths or Dakota. Being a keen young chap in those days I was also ever on the lookout to fly a Vampire or a Mustang in between instructor course sorties. There was no doubt about it, East Sale was a pilot’s paradise!

The base was also the home to the RAAF Schools of Air Traffic Control, and Air Armament, where future tower controllers learned their trade and across the road Lincoln air gunners were taught how to shoot down fighters and strafe ground targets. Although Lincolns carried two 20mm cannons in the mid-upper turret and O.5 inch calibre machine guns in the nose and tail turrets, everyone knew that in real life the aircraft stood little chance against a determined fighter attack, simply because it was too slow and cumbersome. Fighter affiliation exercises were used to train air gunners to fire at a fast moving fighter. Gunners were born optimists and they needed strong stomachs to counter the extremes of attitude needed to out-turn fighters. During the war, rear gunners especially, suffered high casualties as enemy fighters would invariably aim to kill them before they could defend their aircraft from rear attacks.

During training at Air Armament School a Mustang would attack the Lincoln by launching an attack from behind the bomber. In turn, the Lincoln pilot would counter with a violent evasive action known as the Corkscrew. This involved a series of steep climbing and descending turns designed to make it difficult for the fighter to bring its guns to bear on the bomber. I always had doubts upon the value of the corkscrew because there was a short period during the turn reversal where the bomber made an easy target for the fighter. Over Europe American bombers flew daylight mass formations which allowed hundreds of machine guns in a formation to fire at each fighter. Only single bombers could afford the room to corkscrew.

Many years later in 1999, I was privileged to listen to Squadron Leader Tony Gaze DFC who had been invited to give a talk on his war experiences to the Melbourne Branch of the Aviation Historical Society of Australia. Tony was a former Spitfire pilot in the RAF who had flown on operations over Europe alongside the famous RAF aces Douglas Bader and “Johnny” Johnson. We discussed the effectiveness of the corkscrew technique against fighter attack. Tony decried the manoeuvre, stating that many Allied bombers had been shot down while corkscrewing. He said that during the reversal turn by the bomber it offered a no deflection shot to its attacker and that in his point of view, the only defence for a single bomber was to haul into a continuous steep turn in an attempt to force an attacker into inaccurate high deflection shooting. It was my impression back in 1955 that very little had changed in bomber versus fighter tactics and that the bitter lessons of the last war had never reached the gunnery instructors at East Sale.

When No 14 Flying Instructors course started on 17th August, my instructor was Flight Lieutenant Randal Green – inevitably known as Randy Green. He was an enthusiastic chap and a fine instructor. There was never a harsh word, despite the many times I made a hash of learning the art of “pattering” a sequence. I have always spoken too fast and he would gently rubbish my rate of speech as soon as I got up to speed during a patter session. I never minded this as it was done with gentle humour and I soon learnt to slow down. His patient manner made the course most enjoyable. Unlike years later when one occasionally suffered the arrogance of airline check captains who were legends in their own minds.

No. 14 Flying Instructors Course, Central Flying School, East Sale.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Standing L-R: John Laming, Ron Bastin, Viv Barnes, Lloyd Knight, Ken Duffy, Ed Plenty, Dave Smithies, Doug Johnson, Reg Jones, Stan Hyland. Seated L-R: Roy Hibben, Roy Scaife, Alan Mann, Bill Hughes, Griff Boord, George Watkin, Bob Baddams, Dal Oswald.

Randy was responsible for training three students. These were Flight Lieutenants Reg Jones and Griffith Boord, and myself. Reg was a fighter pilot who had recently returned from a posting flying Vampires with the RAAF 78 Wing based in Malta. A quiet unassuming man, he lost his life a few years later during the four-ship accident to the RAAF aerobatic team known as the Red Sales. Griff Boord was also a fighter pilot who had flown Meteors operationally in Korea. Griff was to die of a heart attack in later years.

The others on No 14 FIC were a cross-section of pilots from transport, bomber, fighter and maritime reconnaissance squadrons. The CFS instructors were a varied lot – as was their talent at teaching others. Many had flown on operations during the war. All had previously instructed at Point Cook and were now here to teach others how to instruct. We were lucky to have such depth of experience among them and I cannot help but contrast these people with today’s crop of young civilian instructors who have chosen not to venture beyond the comforts of their local aero club.

CFS names in my log book of 1955 include Ken McAtee, Ken Andrews, Snow Joske, Jack Carter, Ron Graham, Jim Graney, Herb Thwaites (who died in 1996), Denys Smallbone, Peter Badgery, and Gus Goy. The CFI was Squadron Leader Jim Graney AFC with Wing Commander John Dennett as Commanding Officer.

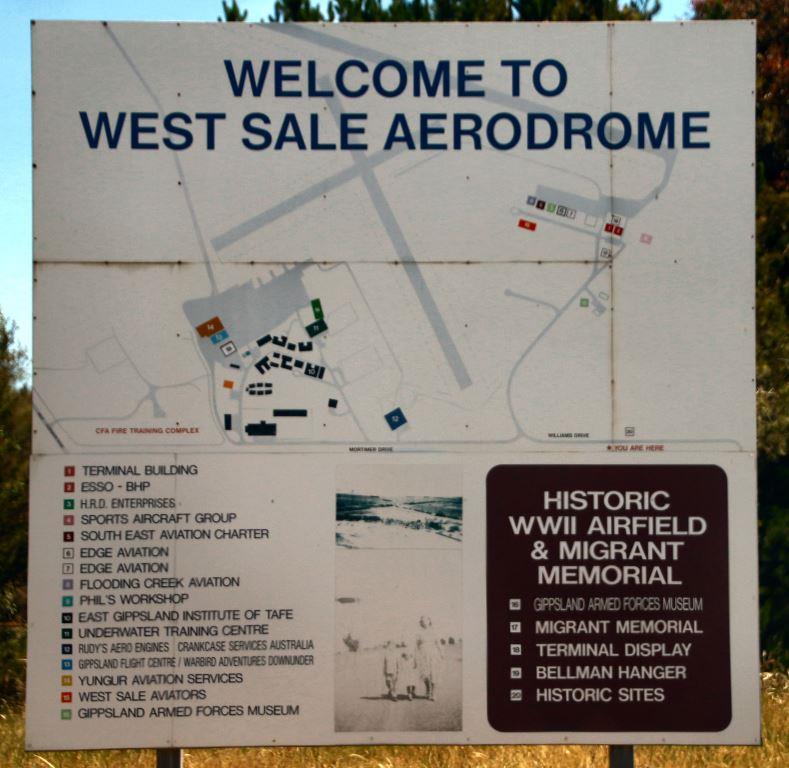

The day would start with staff instructors and students assembled at A Flight hut, where the CFI or his deputy would brief on instructor duties and aircrew notices. Following this, the civilian meteorological officer would give the daily weather briefing while the Senior Air Traffic Control (SATCO) gave the run down on navigation aid serviceability and aerodrome status both at East Sale and at the satellite field of West Sale situated 10 miles away.

West Sale was used primarily for the Tiger Moth phase of the course in order to avoid the problem of faster traffic in the circuit area at East Sale. A Tiger would be on its back in a flash if too close behind a landing Lincoln.

A CFS staff instructor would give the first mass briefing of the day. This could include such things as Climbing and Descending, Forced Landings, Low level Navigation and so on. Afterwards, students and instructors would gather about the stove for coffee and then disappear into individual instructor briefing rooms for pre-flight discussions. Outside on a tarmac, swept by freezing winds or drizzling rain, the ground staff in dark blue overalls were pre-flighting aircraft. Refuelling trucks supplied 100 octane fuel into Mustangs and Lincolns of the Air Armament School and the Dakotas of the School of Air Navigation. While CFS instructors and students gathered for the day’s work, similar briefings took place in the warmth of the flight huts of AAS and SAN just down the road. Scheduled for fighter affiliation exercises, crews lugged their navigation bags and parachutes up the front ladder of the Lincolns while a Mustang pilot was helped settle into his cockpit by waiting ground crew.

On the 8th of September I flew twice in Tiger Moths and then acted as

second pilot to Squadron Leader Ken Andrews on his first night command

trip in a Lincoln. Ken was a smooth pilot with a relaxed friendly

manner. Forty years later he was still in the game – this time as a

civilian instructor at Bankstown. I underwent a routine flight progress

test in a Tiger Moth with Squadron Leader Herb Thwaites, a CFS flight

commander. Years

Click the pic for a copy of the Coroner’s Report into the accident.

After I had pattered a forced landing from 3,000 ft Herb asked me to demonstrate my aerobatic skills. I dreaded this because being rather short in the legs I have always had difficulty in getting full rudder on while carrying out slow rolls. This was the case today when I tried to talk myself through a slow roll. The poor old Moth fell out of the sky upside down leaving me still talking ten to the dozen after the aircraft had given up the ghost. I think Herb’s crook leg was paining him because he did not attempt any more demonstrations. After landing and a debrief he sent me up for more aerobatic solo practice. Later when I did my final handling test with the CFI, I had the same problem. I simply could not reach full rudder and did not enjoy aerobatics in the open cockpit Tiger Moth. I even tried slackening my safety harness so that I could stretch one leg further.

That seemed to work for a while, but as soon as we were inverted I floated clear of my seat and was restrained from falling overboard only by my harness. I nearly choked on the Gosport Tube as my patter went out the window and I felt a right twit. The CFI was nothing if not pragmatic. After he had demonstrated a perfectly executed slow roll he handed back control to me saying that if possible I should avoid teaching slow rolls to students in the Tiger as I would surely bugger them up. I was grateful for his advice even though it was delivered with a touch of biting sarcasm.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Reg Jones, Randy Green, John Laming.

|

||

|

A few days later I got my hands on Mustang (A68-118) and merrily rolled my way around the sky. Being solo, there was no one around to see me dishing out of slow rolls. Someone suggested a big fat cushion behind my back allowing me to apply full rudder extension. That seemed a good idea so I got an airman fabric worker from Safety Equipment section to manufacture one for me. He even stencilled my name on it. The trouble with big fat cushions in a Tiger Moth was that if dislodged, they could fall overboard from the open cockpit and with my luck would be bound to land on the head of a passing member of the constabulary. What with my name stencilled all over the cushion in large letters, it would not take much effort for a budding Sherlock Holmes to trace its owner. It’s called Murphy’s Law.

My short stature also caused me grief when flying from the back seat of the Wirraway. This aircraft was a real beast if allowed to swing on take off and landing and it took immediate full rudder to stop an impending ground loop. Certainly, the rear cockpit rudder pedals were designed with six footers in mind. At CFS, ground staff designed wooden blocks that screwed on to the rudder pedals giving an extra couple of inches to the short pilots.

While that helped, the flip side was that “feel” was missing, making it

easy to inadvertently apply too much brake – and so the inevitable swing

would

On the 26th of October I was scheduled for a 25 hour progress test on the Wirraway. Now that was one trip I shall never forget. My instructor for the test was Flight Lieutenant Denys Smallbone, a Royal Air Force exchange officer from CFS at Little Rissington in England. Denis was a delightful chap with an impish sense of humour.

The progress test covered the whole gambit of aerobatics, stalling, spinning and general instructor patter. I occupied the instructor seat in the rear cockpit while the CFS instructor acted the part of a student pilot sitting in the front seat. The view from the back was severely restricted by the instrument panel. This made things tricky when the tail was on the ground during the early part of the take off run and when the tail was lowered during the landing run. Night flying from the back seat of the Wirraway was a health hazard.

The CFS instructor set the scene by announcing that for the purposes of this progress test I was to call him by his invented student’s name of Hogglebottom. That was a mouthful and we hadn’t even got airborne yet. The first patter sequence was taxying. The game plan called for the instructor to demonstrate how to taxy a Wirraway, then stop the aircraft and hand over control of the aircraft for the student to have a go. I pattered away merrily and then stopped the Wirraway on the long taxiway leading to the threshold of runway 27. So far, so good except that I had not noticed the presence of a bloody great Lincoln bomber following close behind us to the runway. Unlike the Mustang there was no rear vision mirror. Denys Smallbone, (aka Hogglebottom), had seen the Lincoln but chose not to tell me. Within seconds of my handing over control to Trainee Pilot Hogglebottom, he suddenly applied hard brake causing the Wirraway to swing through 180 degrees facing the way we came. Too late to stop the swing, I stared in dismay at the sight of the Lincoln bearing down upon us fifty yards away. The Lincoln pilot hit his own brakes and stopped with a jerk with four propellers rapidly being brought back to idle.

Smallbone laughed his head off while stammering an acted apology for his lead footed taxying skills. The Lincoln pilot meanwhile showed little sympathy for my plight and shoving his head out of the cockpit window 18 feet above the ground gave us the classic two finger salute indicating that we should get out of his way. I thought stuff him – I have got my own problems with Hogglebottom and this son-of-a-bitch of a Wirraway!

I nearly dislocated my knee bone trying to coordinate rudder and brake with full back stick and much roaring of the Wasp engine in order to head back towards the runway. That done I waited for the next trick from my friendly CFS instructor. We got airborne and climbed to height for aerobatics practice. I pattered and demonstrated with great aplomb with little action from the front cockpit. I was being lulled into a false sense of security as it turned out.

I had just pattered a stall recovery when Smallbone took over control to act as a student carrying out his first stall. With flaps down, if the stall recovery is not precise and prompt, the Wirraway will flick inverted and spin. Today we were at 8,000 feet above West Sale aerodrome with Tiger Moths pottering around the circuit pattern far below at 80 knots. Before carrying out stall recovery practice it was usual to carry out a steep turn to ensure that there was no aircraft immediately below us. Hogglebottom heaved into the steep turn with a viciousness that caused me to temporarily grey-out for a couple of seconds. I was about to tell him to ease up on the G forces when without warning the Wirraway flicked inverted and began to spin. After a couple of turns I told the student to recover from the spin. This normally required full opposite rudder to the direction of spin, followed by an easing forward of the stick to un-stall the wings.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Hoggelbottom did not reply, and the aircraft continued to spin. Again I told him to take the necessary recovery action but still he held on to the controls and said nothing. I then raised my voice and told him sharply to recover. He said that he was scared and did not know what to do.

West Sale railway station was spinning crazily over the front of the engine cowl and I attempted to take over control – only to find that Hogglebottom had frozen on the controls. By now we had lost several thousand feet and I thought the CFS instructor was taking the joke too far.

After failing to overpower his grip on the controls I finally spat the dummy, swore at him, and told him in no uncertain terms to release the bloody controls forthwith. The instructor laughed and let me take over control. He then made the point that if a student panics and freezes on the controls, a string of oaths from the instructor may snap the student out of his frozen state. So far I have yet to meet any panic-stricken students so I have never had the opportunity to try out his theory.

When we returned to the circuit, Smallbone told me he would fly a short field landing and that I was to take over control if he made any serious mistakes. As explained earlier, the Wirraway was renowned for its vicious wing drop at the point of stall. I was worried that if his spin recovery was an example of testing me to the limit, then a short field landing cock-up was bound to be his last throw of the dice on my test. He approached the runway just above the stall, while I crouched uneasily over the controls in the back seat waiting for the inevitable wing drop that I was sure Smallbone would try to induce. To my relief his touch-down was smooth and right on the end of the runway.

There was no doubt that Denys Smallbone was a very skilful pilot. The

landing is not over until the aircraft is stopped – or so goes the old

adage – and I waited for his next move. Perhaps he would allow the

aircraft to swing badly at the next taxyway turn-off. It didn’t happen,

but I didn’t relax until the chocks were under the wheels. Coffee

around the pot belly stove never tasted as good as that day. Smallbone

seemed happy with the trip and I was

A quick check in the telephone directory revealed an M. Smallbone living at the tiny village of Port Albert on the coast of Bass Strait which separates mainland Australia from Tasmania. My phone call was answered by a lovely voice belonging to the 80 year old Mrs Denys Smallbone. She was fit and healthy and was engaged in laying some concrete for her garden when I rang and explained that her husband had been my instructor at CFS nearly 46 years ago. She was delighted to hear from me but she had some sad news, too. Denys Smallbone had died at the age of 74 nearly five years ago. Nice bloke was Denys – but I’m not sure about the redoubtable Hogglebottom, who caused me much angst yet so much hilarity at CFS.

In November 1955 I flew 32 trips – often four in one day. For example on 3rd November the first trip was in Mustang A68-119 on formation flying with Flight Sergeant Brian Holding who was in another Mustang. Brian and I had been on the same pilots’ course in 1952. After graduation he had flown Mustangs and Vampires at the Operational Training Unit at Williamstown before being posted to Korea where he flew Meteors on United Nations operations against communist North Korea. Many years later he became a senior captain with Trans Australia Airlines. Following the formation practice, I attended a briefing at CFS on air to ground gunnery techniques, followed by a dual period with Randy Green in Wirraway A20-732.

For this sortie, two 0.303 machine guns were installed under the wings. I’m not quite sure if we used a simple ring and bead or a reflector gunsight. Either way, I was a lousy shot and got very few bullets on the target. Then it was lunch time at the Officers Mess for Randy and the other officers, while I wandered to the Snakes Pit (Sergeants Mess) for a three course meal with the NCO members of our instructors course.

At 1300 the course was back down to the CFS flight huts where Randy and

I climbed into Wirraway 732 again – this time swopping seats. He

View from the front seat.

Now the view from the back of a Wirraway is none too good and becomes positively frightening in a 45 degree dive. It is well nigh impossible to sight the ground target which consisted of canvas strips laid flat in the sand. Observers watch the diving aircraft while crouching in concrete bunkers safe from stray rounds. Their job is to observe and record the number of bullets that hit or miss the target.

Over the target I did a classic wing-over just like the Stuka dive-bombers you see in old war movies. You needed to have the rear canopy open in order to stick one’s goggled head into the slipstream to sight the target. From the back seat that is about the last time you can actually see the target – the rest being a case of pointing down and shooting in the general direction of Australia. The observers in their bunkers knew well the dangers of sticking their necks out whenever instructors course gunnery was on. My scores from the back seat revealed nil bullets located on the target although spurts of dust were seen a football field length away. Whether or not the dust was due to bullets hitting the ground, or rabbits running at warp speed for cover, will never be known. Maybe both. The main thing was that particular box in the flying syllabus was ticked off in our training records. We returned to base with empty guns and the debrief by Randy Green was mainly chortles of laughter. I remained tight lipped and glum as our scores were posted on the crew notice board. Not that I lacked a sense of the ridiculous, but after all a man has some pride. I found myself airborne again half an hour later in Wirraway A20-661 with Pilot Officer Alan Mann in the back seat practicing mutual patter on aerobatics. Alan was a graduate of No 7 Pilots Course. He had flown Dakotas and both he and I were to be posted to No 1 Basic Flying Training School after graduation as flying instructors. I liked Alan Mann. He was quite unflappable and easy going with a dry sense of humour. In years to come he became a captain with Qantas.

At Uranquinty he had a student who on one particular dual flight became

quite upset with himself after some problems with his flying. After the

flight Alan Mann wrote up his students hate-sheet (progress report),

adding that “student cried like a bugle player”. The flight commander

at No 1 BFTS, Flight Lieutenant Val Turner DFC (right) was a former

wartime fighter pilot not known for his fatherly approach to students

and instructors alike. He

To my chagrin I discovered too late that I had forgotten to bring my charts in the aircraft and was forced to admit shamefacedly over the radio that I did not know how to locate the tunnel. After landing I received a well deserved blistering attack by Turner on my lack of airmanship and was given the punishment of walking the perimeter of the airfield carrying my parachute over my shoulder. Never did a parachute feel so heavy.

15th November saw our course undergoing dive-bombing using six 5 kg practice bombs per sortie. I shared four trips in one day with other trainee instructors. This time my scores were marginally better than the gunnery debacle. The technique was to fly a left hand circuit over the bombing range at 3000 feet, then on base leg carry out a wing over into a 45 degree dive angle. The throttle was partially closed to avoid propeller overspeed and also to keep the airspeed manageable. At 1500 feet a single bomb was released followed by a straight pull-out of the dive. By this time the Wirraway had reached 800 feet at the bottom of its dive. Once the climb was established wings level, a climbing turn to 3000 ft was made back on to the downwind leg. The exercise was repeated using the five remaining bombs. During the climbing turn it was possible, by craning one’s neck, to spot the smoke of the bomb burst.

|

||

|

The man who invented auto text has died; his tombstone contains the words 'Restaurant in Peace'

|

||

|

Like gunnery, dive bombing from the back seat of the Wirraway was always a blind hit or miss affair. There was however one real danger that we were briefed to avoid. It concerned the “g” limits of the aircraft. The Wirraway, if I recall, was a strong aircraft with an ultimate breaking load of around 8g. This was providing that the pull was equal on both wings. We were warned to avoid high rolling “g” where the twisting moment of unequal force could drastically lower the normal limit. This danger was tragically confirmed when a Wirraway lost a wing during practice dive-bombing near Point Cook a few months later. The pilot was Flight Sergeant Ted Dillon, a flying instructor at No1 Advanced Flying Training School. Ted was a dare-devil type who had flown Meteors and loved low flying. Earlier he had a lucky escape from disaster when his Wirraway hit a tree while on a low flying exercise.

Ted knew that greater bomb aiming accuracy could be attained by increasing the angle of dive beyond the briefed 45 degrees angle. During instructor practice he would close the throttle in order to keep the dive speed back and invariably commenced his pull out lower than most other pilots.

On one of his dive-bombing runs at the Werribee bombing range near Point Cook, his aircraft was seen to pull out sharply after bomb release and at the same time instead of a wings level recovery, a hard rolling pull-up was started. Witnesses saw one wing separate from the aircraft which immediately crashed. Ted was killed instantly. Many years later I still use the example of Ted’s crash to illustrate the dangers of rolling “g” to pilots undergoing unusual attitude recovery training in the Boeing 737 full flight simulator.

17th November 1955 was a memorable day. It started with one dual and one

mutual trip in Wirraway 732 with Randy Green and Flight Lieutenant Griff

Boord respectively. The sequences pattered included aerobatics,

instrument flying, practice forced landings and circuits and landings.

Griff was a RAAF College graduate of 1950 who had flown Meteors in Korea

and after tours as a fighter pilot at Williamstown was posted to our

course No 14

After sharing the mutual instructor period with Griff, I was then scheduled to undergo a dual flight in a Vampire Mk 35 (two seat) with another flight commander, Squadron Leader Ken Andrews. His nickname was Chu Chu after his propensity for offering his students lollies after a flight and saying “Here – have a chu-chu”.

I had flown several hours on single seat Vampires, but only one hour on the dual version four years previously. The Mk 35 Vampire had a cockpit canopy which was a clam-shell type rather than the more common sliding canopy found on the Mustang, Sabre, and Vampire Mk 31. As some of the instructor course pilots had not flown jets, CFS had decided that a jet familiarisation flight would be a good thing. Accordingly, Ken Andrews took me up in the dual Vampire for a bit of horsing around in the upper levels. The dual Vampire was very cramped in the cockpit and those instructors who eventually taught students to fly Vampires were subject to re-occurring back problems in later years.

The Vampire has a very limiting fuel endurance of just over an hour and

after a couple of touch and go landings, Ken decided his back was too

sore for more. Parked on the tarmac, he closed down the engine and

opened the canopy allowing us to vacate the cockpit (or egress, as the

Yanks say).

Gratefully I took this advice on board and decided to let Ken vacate the cockpit first – age before beauty so to speak… Well, just like the man said, the canopy was not correctly locked open and Murphy’s Law was self actuated. As Ken placed both hands on the windscreen bow to lever himself out of the left seat, the canopy fell down with a bang, trapping his fingers akin to a slammed door. He gave a frightful well mannered oath something along the lines of “Scheissenhausen” which, translated from the German, means shithouse (or something like that), and sat back among a tangle of oxygen, radio, and dinghy leads, wringing his squashed fingers in obvious severe pain.

I sympathised and muttering something about “there but for the grace of God go I”, couldn’t help remarking to Ken that he had given a bloody good demonstration of the dangers of unlocked canopies. By this stage, the normally urbane Squadron Leader K. Andrews – “A” Flight Commander, Central Flying School, had lost his cool and snarled back at me that my remark was not funny. That was a matter of personal opinion of course, although I must say that I felt that then was probably not the most appropriate occasion to fall over laughing. For the next few weeks Ken was off flying with his fingers in splint looking like an indignant version of Napoleon without his Josephine.

That evening I was scheduled to fly as second pilot to Alan Mann on night flying in Lincoln A73-1. We carried out several touch and go landings interspersed with one engine feathered landings. While the Lincoln was a good performer on three engines, things could become a bit unstuck when it came to going around again with one feathered if the speed was allowed to deteriorate below the safety speed of 120 knots.

As the landing speed of the aircraft was around 100 knots, it takes little imagination to imagine what would happen during a three engine go-around at that speed. The aircraft was a conventional tail-wheel design and that means they can really bounce unless care was taken to carry out a smooth landing. After losing three Lincolns that bounced badly and attempted to go-around during practice feathered landings, the RAAF - rather belatedly in my view - banned the exercise as too dangerous. In fact, the RAAF lost more Lincolns practicing feathered landings than with real engine failures.

|

||

|

|

||

|

In later years as a flying instructor at No 10 Squadron at Townsville, that directive was to save my skin one night. I had been giving dual instruction on a new pilot and the exercise called for simulated feathered landings with the “dead” engine at idle power. This was known as zero thrust. The advantage being that the drag of a throttled back engine simulated that of a feathered propeller with the advantage that in event of a bad bounce or late go-around, the closed throttle lever could simply be brought back into action. On that night, the new pilot who only had 220 hours in his log book, was doing very nicely and coping well with a simulated engine failure on take off.

Downwind on three engines, with the fourth engine idling at zero thrust, the student requested landing gear down and one quarter flap to be set. This was a standard asymmetric configuration. When I selected the flap lever to down, it broke away in my hand leaving the hydraulic selector valve in the full flap down position and uncontrollable.

The Pilots Notes for the Lincoln warned that on a go-around with full flap, immediate flap retraction to half flap was needed to avoid a strong nose up change of trim. Failure to act could lead to the nose rising and loss of forward elevator effectiveness. On three engines this could be highly dangerous due to airspeed loss and thus loss of rudder control.

In our case, the flaps went to full down and up went the nose with a vengeance. I brought the fourth engine back to full power along with the other engines. This only exacerbated the pitch up, but with a rapidly deteriorating airspeed we were damned if we did and damned if we didn’t. Fortunately, I was able to bring the situation under control and we landed safely. If by the previous rules of engagement, we had flown the circuit with one engine feathered, I believe we would have been in serious control difficulties. After that I mentally thanked the wise headquarters staff officer who placed the kibosh on practice feathered landings.

If there was a funny side to it, it was when the new Lincoln pilot initially thought that I was merely attempting to demonstrate an unbriefed runaway flap control. He must have been kidding. At night, with one engine throttled back? No bloody way!

Three years earlier therefore, during the night circuits at CFS as second pilot to Alan Mann, I was blissfully ignorant of such potential dangers and happily feathered his engines on request.

1st December 1955. Busy day, flying five sorties. These included a test flight after a Lincoln major inspection, an instrument rating test by CFS instrument rating examiner (IRE) Flight Lieutenant Ron Graham, and three Wirraway dual and mutual instructor training sorties. The Lincoln flight was carried out at 5000 feet and involved feathering each of the four Rolls Royce engines – one at a time, of course. Acting as second pilot was Warrant Officer Fisher, a wireless operator/gunner. The Lincoln was designed as a single pilot aircraft although we usually carried a second crew member for safety reasons. If a qualified pilot was unavailable we would grab the nearest volunteer – ground staff or half-wing aircrew – to operate the flaps and undercarriage and help start the engines. There was rarely a shortage of someone to sit up front to enjoy the shattering noise of four Merlins at take off power. W/O Fisher drew the short straw on this occasion.

After carrying out all the mandatory tests on the Lincoln (A73-1, again) I was about to return to base when we spotted three Wirraways below us in formation. Their pilots were Randy Green and Viv Barnes flying dual, plus Roy Hibben and Bill Hughes All were fighter pilots and good for a spot of fun. Mock dog fighting was permitted in the training area and so rolled over I dived behind them in a quarter attack. As the Lincoln could cruise at least 50 knots faster than the Wirraway it was no trouble to catch up with them. After a little horseplay it was mutually agreed by radio that they could practice formation flying on my Lincoln. To reduce speed to their level it was necessary to lower the flaps and open the bomb doors to create some drag.

That done, we cruised sedately around the sky at 120 knots with the Lincoln the centre of attraction. A Wirraway sat on each wing-tip and another slid in behind in close line astern. I think Roy Hibben was flying the line astern position and he came in real close until he could look up and into the cavernous bomb-bay of our Lincoln. Remember this bomber can carry over 20,000 lbs of bombs – so it has a fair size bomb-bay.

|

||

|

If the person who invented the drawing board got the initial design wrong, what would they do next??

|

||

|

It is heavy work flying a Lincoln – there are no powered controls – and after a few formation turns I decided it was time to go home. Calling the others by radio that I was breaking off the exercise, I asked the second pilot to pull up the flaps while I closed the bomb doors. I had no idea that Hibben was almost directly underneath our aircraft. He was caught by surprise at the sink caused by the retraction of flaps, and his Wirraway was nearly squashed beneath us. It was only his quick reaction in diving away from the fuselage of the Lincoln that saved what could have been a nasty accident. A Court of Inquiry would have crucified me for playing with Wirraways while on a test flight.

|

||

|

|

||

|

A few days before qualifying as a flying instructor in mid-December 1955, I managed to talk my flight commander into letting me fly two more trips in a Vampire plus a final go in a Lincoln and Dakota. The Vampire was a single seat Mk 30 version A79-1. It did not have an ejection seat. The cloud base was low at 200 feet and after a VHF/DF instrument let down I was fortunate enough to get talked down by Ground Controlled Approach (GCA). This is a remarkably accurate final approach by a radar controller. With no radio navigation aids in the Vampire, a pilot was entirely dependent on the skill of a radar operator in a truck near the runway to get back on to the deck. A serious limitation of GCA was rain attenuation where the aircraft echo could be lost in screen clutter caused by reduction of radar efficiency in heavy precipitation. In later years I realised with some guilt that I never thought to say thanks to these unknown air traffic controllers who spent hours in a cramped van either freezing or sweating depending on the season. Thanks chaps, if you happen to read this nearly fifty years later.

A few days before the end of the instructor’s course we were checked out on the new Winjeel basic trainers. My first dual flight was on A85-804, followed by sorties in A85-404, and 406. At the time we felt that it would be a big jump for student pilots on Tiger Moths to the heavier and faster Winjeel. We were wrong as it turned out, and the time to first solo on the Winjeel averaged 8-10 flying hours. The Winjeel proved a successful ab-initio trainer and as with Tiger Moths, new students transitioned from Winjeels to Wirraways within five hours.

The QFI course at East Sale was sheer enjoyment and I was indeed fortunate in having Randy Green as my instructor throughout. He taught me that patience and good humour are amongst the vital attributes of a good instructor. Having been given curry by the odd pompous airline check captain that I was unfortunate enough to encounter in my later civilian career, I will always regard Randy Green as one of the finest instructors that I have flown with. Thanks Randy – if you happen to read this story. I owe you.

They were halcyon days at East Sale and many years later it is nice to still run into some of the many friends that I made around the old pot belly stove

|

||

|

My wife says that I never listen to her - or something like that.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

train from Townsville to Brisbane then boarded a TAA DC4 to Sydney where

my wife Loretto and I stayed a few days with her parents.

train from Townsville to Brisbane then boarded a TAA DC4 to Sydney where

my wife Loretto and I stayed a few days with her parents.

re-occur.

At East Sale on 20th October, while taxying for take off, a Wirraway

ground-looped causing the undercarriage to collapse. The pilots were Roy

Hibben (left) and Ron Bastin. Both were of short stature like myself and

I wondered later if one of them had run out of rudder control. The

accident didn’t harm their careers, however. Hibben went on to become a

Wing Commander winning a DSO with 9 Sqn in Vietnam, (see

re-occur.

At East Sale on 20th October, while taxying for take off, a Wirraway

ground-looped causing the undercarriage to collapse. The pilots were Roy

Hibben (left) and Ron Bastin. Both were of short stature like myself and

I wondered later if one of them had run out of rudder control. The

accident didn’t harm their careers, however. Hibben went on to become a

Wing Commander winning a DSO with 9 Sqn in Vietnam, (see

relieved to pass the hurdle of the 25 hour progress test. In later years

Denis migrated to Australia and became the Reverend Smallbone of an

Anglican church in Gippsland, Victoria. When writing this story I

wondered if Denys Smallbone was still around and if so, would he recall

his alter ego Trainee Pilot Hogglebottom.

relieved to pass the hurdle of the 25 hour progress test. In later years

Denis migrated to Australia and became the Reverend Smallbone of an

Anglican church in Gippsland, Victoria. When writing this story I

wondered if Denys Smallbone was still around and if so, would he recall

his alter ego Trainee Pilot Hogglebottom. became the student in the front seat while I flew from the back seat. My

job was to patter a ground attack then give my student a go at firing

the guns.

became the student in the front seat while I flew from the back seat. My

job was to patter a ground attack then give my student a go at firing

the guns.  scrawled a note over Mann’s remarks which said: “Pilot Officer Mann –

we are training pilots – not bloody bugle players”. I had tangled with

Val Turner a couple of years previously during a fighter pilots course

that I attended at Williamtown (not very successfully, I might add).

While flying a Vampire in formation with Turner in another Vampire, he

ordered me to take over as leader and take us to a railway tunnel in the

countryside near Williamtown.

scrawled a note over Mann’s remarks which said: “Pilot Officer Mann –

we are training pilots – not bloody bugle players”. I had tangled with

Val Turner a couple of years previously during a fighter pilots course

that I attended at Williamtown (not very successfully, I might add).

While flying a Vampire in formation with Turner in another Vampire, he

ordered me to take over as leader and take us to a railway tunnel in the

countryside near Williamtown. FIC. He was a pleasant fellow, well liked by all. With him at CFS was

another graduate of RAAF College. This was Flight Lieutenant Henry

(Bill) Hughes (right) who had won a DFC in Korea. Bill was an

outstanding officer who eventually rose to Air Vice Marshal rank.

FIC. He was a pleasant fellow, well liked by all. With him at CFS was

another graduate of RAAF College. This was Flight Lieutenant Henry

(Bill) Hughes (right) who had won a DFC in Korea. Bill was an

outstanding officer who eventually rose to Air Vice Marshal rank.

After unclipping my oxygen mask, radio leads and parachute, I grasped

the front windscreen and started to haul myself up and out of the

cockpit. Immediately Ken warned me of the dangers involved of climbing

from the Vampire without first ensuring the canopy was correctly locked

in the open position. He explained that an unsecured canopy could slam

down and cause grievous bodily harm to anyone foolish enough to have his

fingers in the way.

After unclipping my oxygen mask, radio leads and parachute, I grasped

the front windscreen and started to haul myself up and out of the

cockpit. Immediately Ken warned me of the dangers involved of climbing

from the Vampire without first ensuring the canopy was correctly locked

in the open position. He explained that an unsecured canopy could slam

down and cause grievous bodily harm to anyone foolish enough to have his

fingers in the way.