|

|

|

|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 38 Page 15 |

|

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

|

|

|

|

|

RSL AND SERVICES CLUBS.

There are

now new club entry rules in force for RSL members and Defence personnel.

Legislation granting current serving and ex-service Australian Defence

Force personnel entry to RSL and services clubs as ‘honorary members’

without the need to ‘sign-in’ is now in force in New South Wales, as

well as Victoria and Queensland.

Under the newly introduced NSW provisions, ‘service members’ of the RSL and current serving Australian Defence Force personnel (including Reservists who also carry the same card) are granted ‘honorary membership status’ for the day they attend the club on producing either their Defence Force ID card, or for ex-servicemen and women their membership card of the Returned and Services League Australia, which is now uniform across the country.

It will be a requirement that members of the RSL also produce evidence of membership of at least one RSL or services club. The new rule applies to RSL, Services, Ex-services, Memorial, Legion or other similar registered clubs, or a registered club that has objects similar to, or is amalgamated with an RSL or kindred club.

The new NSW RSL membership card stipulates in the bottom left corner whether the card holder is a ‘Service Member’ of the RSL or may denote that the holder is a ‘Life Member’ or ‘Life Subscriber Member’, both of which are recognized under this provision. Queensland RSL Members have a similar card, and the RSL Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania membership card also notes the club of which they are a member.

The recognition of this honorary status will bring NSW into line with similar requirements which already exist in Victoria and which have also just been passed in Queensland. The NSW provisions were introduced by the new State Government in recognition of the service by current Defence and ex-service men and women to their country. It will now allow the RSL and Defence Force members easy access to RSL and services clubs as they travel around the state and in Victoria and Queensland.

The new legislation carries forward the previous provision allowing such ‘honorary members’ to sign in their family and friends. Reciprocal rights for RSL members has been a long-term goal of the Association. Due to the array of loyalty programs operating in clubs, it will be up to individual clubs as to whether they extend to these ‘honorary members’ discounts on food and beverage purchases similar to that which they already provide to their club members and which some clubs already recognise

|

|

|

Golfer: "You've got to be the worst caddy in the world." Caddy: "I don't think so sir. That would be too much of a coincidence."

|

|

|

The Key Features of the Defence Sub Branch: The RSL Defence Sub Branch is designed exclusively for serving ADF personnel and will make it easier for serving personnel to join and remain RSL members and access our support and advice services and our venues nationwide. This access and support will include discounts on merchandise and entertainment already available to RSL members and will benefit both the member and their family.

At any time a Defence Sub Branch member can choose to transfer their membership to a "physical" Sub Branch within our 1200 plus nationwide network and of course the establishment of the Defence Sub Branch does not prevent serving ADF personnel from deciding to join a local Sub Branch instead.

The Defence Sub Branch is simply another option which makes RSL membership more accessible, convenient and hassle free given a busy life or postings and deployments.

Supporting the Australian Defence Force

RSL Standing Policy states that the primary objective of Australia's Defence and foreign policies should be to promote Australia's national security and safeguard Australia's vital interests. To meet such an objective, the RSL believes that Australia should maintain:

RSL support points of particular significance are:

|

|

|

No matter what your job, you can always try and make the most of it.....

|

|

|

|

|

|

Golfer: "How do you like my game?" Caddy: "Very good sir, but personally, I prefer golf."

|

|

|

Air France Flt 447.

For more

than two years, the disappearance of Air France Flight 447 over the

mid-Atlantic in the early hours of the 1st June, 2009,

remained one of aviation's great mysteries. How could a technologically

state-of-the art airliner simply vanish? (See Popular Mechanics story

HERE)

With the wreckage and flight-data recorders lost beneath 2 miles of ocean, experts were forced to speculate using the only data available: a cryptic set of communications beamed automatically from the aircraft to the airline's maintenance centre in France. This data implied that the plane had fallen afoul of a technical problem—the icing up of air-speed sensors—which in conjunction with severe weather led to a complex "error chain" that ended in a crash and the loss of 228 lives.

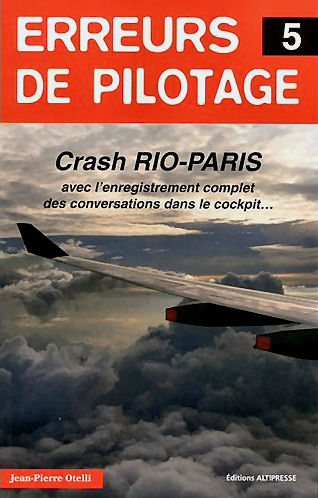

The matter might have rested there, were it not for the remarkable recovery of the aircraft’s black boxes. Upon the analysis of their contents, the French accident investigation authority, the BEA, recently released a report confirming, to a large extent, the initial suppositions. An even fuller picture emerged with the publication of a book in French entitled Erreurs de Pilotage (volume 5), by pilot and aviation writer Jean-Pierre Otelli, which includes the full transcript of the pilots' conversation.

It is now understood that AF-447 passed into clouds associated with a large system of thunderstorms, its speed sensors became iced over, and the autopilot disengaged. In the ensuing confusion, the pilots lost control of the airplane because they reacted incorrectly to the loss of instrumentation and then seemed unable to comprehend the nature of the problems that had caused. Neither weather nor malfunction doomed AF-447, nor a complex chain of error, but a simple but persistent mistake on the part of one of the pilots.

Human judgments, of course, are never made in a vacuum. Pilots are part of a complex system that can either increase or reduce the probability that they will make a mistake. After this accident, the million-dollar question is whether training, instrumentation, and cockpit procedures can be modified all around the world so that no one will ever make this mistake again—or whether the inclusion of the human element will always entail the possibility of a catastrophic outcome. After all, the men who crashed AF-447 were three highly trained pilots flying for one of the most prestigious fleets in the world. If they could fly a perfectly good plane into the ocean, then what airline could plausibly say, "Our pilots would never do that"?

This is a synopsis of what occurred during the course of the doomed airliner's final few minutes.

1h 36m into the flight, the aircraft enters the outer extremities of a tropical storm system. Unlike other planes' crews flying through the region, AF-447's flight crew had not changed their route to avoid the worst of the storms. The outside temperature is much warmer than forecast, preventing the still fuel-heavy aircraft from flying higher to avoid the effects of the weather. Instead, it ploughs into a layer of clouds.

At 1h 51m, the cockpit becomes illuminated by a strange electrical phenomenon. The co-pilot in the right-hand seat, an inexperienced 32-year-old named Pierre-Cédric Bonin, asks, "What's that?" The captain, Marc Dubois, a veteran with more than 11,000 hours, tells him it is St. Elmo's fire, a phenomenon often found with thunderstorms at these latitudes.

At approximately 2 am, the other co-pilot, David Robert, returns to the cockpit after a rest break. At 37, Robert is both older and more experienced than Bonin, with more than double his colleague's total flight hours. The head pilot gets up and gives him the left-hand seat. Despite the gap in seniority and experience, the captain leaves Bonin in charge of the controls.

At 2:02 am, the captain leaves the flight deck to take a nap. Within 15 minutes, everyone aboard the plane will be dead.

02:03:44

The aircraft enters an inter-tropical convergence. An inter-tropical

convergence, or ITC, is an area of consistently severe weather near the

equator. As is often the case, it spawns a string of very large

thunderstorms, some of which stretch into the stratosphere.

02:05:55 The pilots tell the Hosties to get the passengers to buckle up and to sit down themselves.

The two co-pilots discuss the unusually elevated external temperature, which has prevented them from climbing to their desired altitude and express happiness that they are flying an Airbus 330, which has better performance at altitude than an Airbus 340.

02:06:50 Because they are flying through clouds, the pilots turn on the anti-icing system to try to keep ice off the flight surfaces; ice reduces the plane's aerodynamic efficiency, weighs it down, and in extreme cases, can cause it to crash.

02:07:00 About now they realise the radar is not on the correct mode so they change it and find they are heading directly toward an area of intense weather activity so they decide to divert left of track to miss the worst of it.

As they turn to the left, a strange aroma, like an electrical transformer, (often referred to as a ‘brown’ smell) floods the cockpit and the temperature suddenly increases. At first, they think that something is wrong with the air-conditioning system, but then accept the idea that the effect is caused by the severe weather in the vicinity. They decide to reduce speed and turn on the auto igniters which prevent the jet engines from flaming out in the event of severe icing.

Then the autopilot disconnects as the pitot tubes have iced up, resulting in the pilots having to fly the aircraft manually – not an easy job at that level, in bad weather, severe turbulence and without an airspeed indicator or altimeter.

Unfortunately, this is where things really start to go wrong. Instead of diverting around the storm they make an irrational decision and put the aircraft into a steep climb and fly straight into it. The onboard computer reacts immediately and sounds an alarm alerting the pilots that they are leaving their programmed altitude, then the stall warning sounds.

|

|

|

Golfer: "Do you think my game is improving? Caddy: "Yes sir, you miss the ball much closer now."

|

|

|

Stall warning alarms are designed to be noticed. Stalls are very nasty things and usually make the passengers down the back very nervous and this is why stall warnings usually ‘come on’ a few knots before the aircraft actually stalls, this is to give the pilot time to push the nose down and increase airspeed. Even though the stall warning was blaring away quite loudly – the cockpit recorder reports that neither pilot made mention of it – it seems to have been completely ignored and the pilot in command continue to haul back on he controls and the aircraft is soon climbing at the blistering rate of 7,000 feet per minute. As is normally the case, as altitude increases, airspeed decreases and soon the aircraft is flying at only 93 knots.

About now the co-pilot realises something is terribly wrong and he tries to get the pilot to take note of the aircraft’s attitude (nose up) then as the pitot heat starts to work and melts the ice, one of the airspeed indicators shows the perilously low airspeed. The pilot eases forward on the controls and the airspeed starts to pick up and settles at 223 knots, quite safe and once again the aircraft is stable.

Then, for reasons known only to the pilot, he puts the aircraft back into a climb, once again activating the stall warning. By now the pitot heaters have done their job and the pitots begin to function correctly, the cockpit's avionics resume functioning normally and the flight crew now have all the information they need to fly safely. The problems that occur from this point forward are entirely due to human error.

By now, the aircraft had its maximum altitude. With engines at full power, the nose pitched upward at an angle of 18 degrees, it moves horizontally for an instant and then begins to sink back toward the ocean.

Unlike the control yokes of a Boeing jetliner, an Airbus does not have a ‘wheel’, instead it has two side sticks that operate "asynchronously," that is, they move independently. If the person in the right seat is pulling back on the 'joystick', the person in the left seat doesn't feel it, unlike in a Boeing where if you turn one wheel, the other one turns the same way. The co-pilot therefore had no idea that while they are discussing descending the aircraft, the pilot was in fact pulling back on his side stick.

The vertical speed toward the ocean accelerated. If the pilot had let go of the controls, the nose would have fallen and the aircraft would have regained forward speed. But because he held the stick all the way back, the nose remained high and the aircraft had barely enough forward speed for the controls to be effective and as turbulence continued to buffet the plane, it was nearly impossible to keep the wings level.

By now, the Captain, who had been down the back of the aircraft, returned to the flight deck. The aircraft was still in an attitude of 15 degrees nose up, with a forward speed of only 100 knots and was descending at the rate of 10,000 feet per minute. The Captain, for some reason, made no attempt to physically take control of the airplane, had he done so, it is thought he would almost certainly have realised the problem and returned the aircraft to normal flight, instead, he took a seat behind the other two pilots.

As the aircraft approaches 10,000 feet, the co-pilot tries to take over the controls and pushes forward on the stick, but the plane is in "dual input" mode, and so the system averages his inputs with those of the pilot who continues to pull back. The nose remains high. The Captain, at last, realises what is wrong and tells the pilot to push forward on the stick and to regain airspeed. The pilot lets go of his controls and the co-pilot pushes forward and finally puts the nose down and the aircraft begins to regain speed. As they approach 2000 feet, the aircraft's sensors detect the fast-approaching surface and trigger a new alarm. There is no time left to build up speed by pushing the plane's nose forward into a dive and here the pilot panics and pulls his side stick all the way back again. The aircraft hits the water.

Today the Air France 447 transcripts yield information that may ensure that no airline pilot will ever again make the same mistakes. From now on, every airline pilot will no doubt think immediately of AF-447 the instant a stall-warning alarm sounds at cruise altitude. Airlines around the world will change their training programs to enforce habits that might have saved the doomed airliner: paying closer attention to the weather and to what the planes around you are doing; explicitly clarifying who's in charge when two co-pilots are alone in the cockpit; understanding the parameters of alternate law; and practicing hand-flying the airplane during all phases of flight.

But the crash raises the disturbing possibility that aviation may well long be plagued by a subtler menace, one that ironically springs from the never-ending quest to make flying safer. Over the decades, airliners have been built with increasingly automated flight-control functions. These have the potential to remove a great deal of uncertainty and danger from aviation. But they also remove important information from the attention of the flight crew. While the airplane's avionics track crucial parameters such as location, speed, and heading, the human beings can pay attention to something else. But when trouble suddenly springs up and the computer decides that it can no longer cope—on a dark night, perhaps, in turbulence, far from land—the humans might find themselves with a very incomplete notion of what's going on. They'll wonder: What instruments are reliable, and which can't be trusted? What's the most pressing threat? What's going on? Unfortunately, the vast majority of pilots will have little experience in finding the answers.

|

|

|

Golfer: "That can't be my ball, it's too old." Caddy: "It's been a long time since we teed off, sir."

|

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward | |

Unlike other airline company’s aircraft crews, the crew of AF-447 had

not studied the local weather forecasts and had not requested a

divergence around the area of most intense activity.

Unlike other airline company’s aircraft crews, the crew of AF-447 had

not studied the local weather forecasts and had not requested a

divergence around the area of most intense activity.