|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

||

|

Contents:

Flying the Caribou - Chris Jaensch.

|

||

|

My Story |

||

|

|

||

|

JIM (J the T) TREADWELL. AFC, OAM. |

||

|

I was inducted into the RAAF on 1 October 1951 as a member of No 8 Flight Training (FTS) Course with the rank of Trainee Signaller. The initial phase of the Course was held at Point Cook and at the time, Aircrew Training Courses were of 18 month duration. Six months “Initial Training” consisting of drill, Air force Law, administration, and a number of other equally, nasty, subjects, followed by six months Basic Training, when trainees first became airborne and six months Applied Training, to round off the torture.

At the beginning of 1952, after 3 months “Initial Training” at Point Cook and because I had been selected as a Trainee Signaller, I went off to the RAAF Air and Ground Radio School at Ballarat as a member of No 5 Signaller’s Course. Because of the Korean War, with the subsequent loss of a number of Fighter Pilots, FTS Courses were reduced to 15 months. Accordingly, after No 8 course started the initial training phase was reduced to 3 months.

RAAF Ballarat at the time was interesting - for example, it was widely held that the CO, a Wing Commander called Joe Reynolds, was mad. Thinking back I believe this could have been fact.

The WOD was a rather stern individual called “Shagger Marr”. Although he did not carry a stick, every Tuesday, after the weekly CO’s parade, “Shagger” would bellow out: “Fall out the, Roman Catholics, Jews, unbelievers and Pakistani’s” (at the time there were a number of Pakistani’s Air Force people doing radio courses at Ballarat).

If you were unfortunate enough to fall into one of these categories, which included me, you were lined up at the back of the parade and marched off to the Barracks Yard. There to chop the hardest, toughest, Mallee Roots in the Southern Hemisphere. A number of rapid miraculous religious conversions soon materialized from within the ranks.

The Radio School was hard going. The courses were academically demanding and mastering Morse code to the required level was hell. At the time, using high frequency (HF) radio, the Morse code arrangement was the primary form of communication between RAAF Units which included RAAF Headquarters. I had little aptitude for the dits and dars and struggled as a consequence.

Morse training was conducted in four separate class-rooms. The rooms were set up with an instructor at one end with a Morse key with the students scattered around the side of the room wearing headphones. In the first room Morse was belted out at a rate of 10 to 12 words per minute, in the second room 14 to 16 words per minute, and so on through three more rooms until the last where the speed was 22 words per minute. To progress from one room to the next a trainee had to pass five consecutive tests. If you failed one you had to start from scratch all over again.

A test consisted of a five minute burst of six figure code groups and a five minute burst of plain language from a book. Tests were conducted at the end of each session. To pass you had to get 99% of what was sent without an error. At the lower speeds the difference between pass and fail was only two miserable symbols.

I have seen people climb up the wall in frustration after having passed four tests to make one mistake in the fifth and be required to start the process all over again.

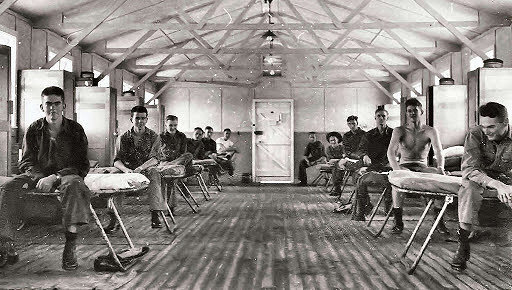

Throughout the period Joe had us doing guard duty at least once, sometimes twice, every week. Guard consisted of two hours on and four hours off – not a receipt for rest particularly when we lived in cold wooden huts and slept on collapsible metal beds. In regard to sleep, in addition to four issue blankets, we piled our RAAAF Great Coats and the bedside mat on top of the bed in an attempt to get, and keep, warm.

Joe held a parade every morning with “Shagger” yelling and screaming. The surface of the parade ground was quartz left over from the Gold Rush. Because of the cold, blokes would stay in bed and not go to breakfast. Accordingly, every morning a number of people would faint and fall, face first, onto the hard quartz with a horrible crunching sound.

Guard duty consisted of stalking around the base in the dark, and cold, equipped with a 303 Rifle (no ammo - could have hurt someone), an axe and a large wooden “Waddy”. The axe was to chop wood for furnaces that generated hot water to outside shower blocks. God knows what the Waddy was for?

The worst part of Guard Duty was associated with two large hangers located remote from the domestic side of the base. It was always pitch black there. In addition, the wind whistled and banged to scare the devil out of the poor unfortunate on guard.

However, these hangers were interesting. A four engine Liberator Bomber was in one and a number of Anson aircraft equipped with early versions of airborne radar in another. In addition, early, portable, ground radars that had been used in the Islands during WW2 the Second War were in a separate compound. I have often wondered what happened to this extremely historic equipment.

At the end of 1952, after finishing the radio and Morse code part of the course, No 5 Sigs course proceeded to the Air Armament School at East Sale for Air Gunnery training in Lincoln aircraft. Great stuff - we blasted away at ground targets at Dutson Live Firing range and at airborne canvas drogue targets towed by Beaufighter aircraft. We fired 50 calibre machine guns from the Tail and Nose Turrets and 30mm Cannon from the Mid-upper Turret.

In December 1952 I received a Signaller’s Brevet at a Wings Parade held at East Sale and even though I could not hit a bull in the backside with a bushel of wheat I graduated “Proficient with Special Distinction”.

Following graduation, I was posted to No 11 Squadron as a Sergeant Signaller. No 11 Squadron was at Pearce operating P2V-5 Neptune Maritime Reconnaissance aircraft. The P2V-5 was equipped with powerful long-range APS-20 radar, precision APS-31 homing-radar, electronic countermeasures equipment, underwater sonar listening gear and a searchlight. Because of this specialized equipment the P2V-5 would have been the first “Weapons System” to enter RAAF Service.

In March 1953 I was a member of the first Neptune crew to attend the Joint Anti Submarine course at NAS Nowra. The course involved a dive in a Royal Navy Submarine and a sortie in the back seat of a Navy Firefly – great experiences both.

It was always my ambition to be a pilot so after arriving at Pearce I spent every penny I could lay my hands-on learning to fly. First at the West Australian Aero Cub, and then, when 11 Squadron moved to Richmond, at the Aero Club of NSW.

After about two years I obtained a Commercial pilot license with an Instructors rating. When this happened, I was offered a job as a flying instructor. I immediately requested a discharge from the RAAF. My request was refused.

However, in April 1955 I was fortunate to be selected for pilot training, the first post-war aircrew member to be selected for pilot training, graduating from No 21 Pilots Course in March 1956 “Proficient with Special Distinction” with the “Goble Trophy” in my hot little hand. We had trained on Tiger Moth and Wirraway aircraft.

A three month Fighter OTU course (No 23) on Vampire Mk 30 aircraft at RAAF Williamtown followed.

After completing the OTU I was posted to 75 Squadron flying Meteor aircraft. In January 1957, I was posted to No 77 Squadron for conversion to Avon Sabre aircraft. In April 1957, I flew the first Sabre (A94-959) which was built at GAC Fisherman’s Bend from Laverton to Williamtown. That aircraft had a very chequered life and was eventually put on display at Fighter World at Williamtown – see HERE (Scroll down)

I was commissioned on 1 January 1957 after promotion to Warrant Officer for one day. I have a framed “Warrant”, dated 1 November 1957, signed by the Air Member for Personnel, Air Vice Marshal Allan “Wally” Walters.

In September 1958 I was posted to No 3 Squadron and took part in operation Sabre Ferry to RAAF Butterworth. In Butterworth I served as a squadron pilot with No 3 and then No 77 Squadron during the Malayan Emergency. |

||

|

|

||

|

In the pic above, I’m on the left of well-known Channel 0 (now Ten) cameraman Mr Peter Purvis of Melbourne, who was filming as a Sabre prepares to scramble at Butterworth. This was in November 1964. I was acting Liaison Officer for a Television documentary, featuring low level runs over the jungle. The documentary was on Australian soldiers serving in Malaya and the coverage of Australian Army Troops in Central Malaya and on the Thai Malay border, as well as RAAF activity at Butterworth.

I just took a leaflet out of my letterbox informing me that I can have sex at 75. I'm so happy, because I live at number 71. So it's not too far to walk home afterwards. And it's the same side of the street. I don't even have to cross the road!

In January 1960 I was posted to “Test and Ferry”, No 2 Aircraft Depot RAAF Richmond, as a Test Pilot. After taking up this position I completed Winjeel and Dakota conversion courses at the Central Flying School (CFS) East Sale.

At the time De–Havilland’s were building Mk 35 Vampire aircraft at Bankstown. Our main job was to test fly these aircraft for acceptance into the RAAF. Another job was to test fly MK 4 Meteors that were shipped out to Fairy Aviation at Bankstown from the UK in boxes. After we flew them, they were fittered with radio control gear and used as targets for missile firing trials at Woomera. The Meteors were very early jet aircraft and did not have an ejection seat or pressurization. With extremely limited endurance they were a bit tricky and needed to be treated with a forked stick.

When the MK 35 Vampire program finished, I did an Advanced Navigation (AN) Course at the School of Air Navigation, East Sale. After the course, I was posted to No 1 Applied Training School, RAAF Pearce, as a Navigation Instructor. During the period I also served, along with Bull Pratt, as Navigator of the SAR Dakota based at Pearce. Whenever there was an emergency, requiring RAAF assistance, Bull and I took it in turns to man the aircraft.

In April 1963 I returned to Malaya as the No 78 Wing Navigation Officer. I remained in No 78 Wing during “Confrontation” although posted to 3 Squadron, as a squadron pilot, in August 1964. During this period I also served in 79 Squadron Ubon, Thailand.

In March 1965 I was posted to 76 Squadron at Williamtown as a squadron pilot. In August 1965 I attended the RAF College of Air Warfare in the United Kingdom to qualify as a GD Weapons Officer. After completing the course, I was posted to No 81 Wing, then at Williamtown, as the Wing Operations Officer. In December 1966 I completed number 7 Mirage III0 conversion course.

In August 1968 I was posted to No 76 Squadron taking command in December 1968. In June 1969 I was posted to No 77 Squadron as CO at the start of the squadron Mirage re-equipment program and while there was called upon to get a Mirage out of the rather short airport at Evans Head (See HERE). In July 1970, after Bill Simmonds took over, I set up the Mirage Photo Reconnaissance arrangement within the squadron as the “C” Flight Commander.

In July 1969, 77 Squadron returned to Williamtown to be re-equipped with Mirages and I was one of the original 5 pilots on type. |

||

|

||

|

Also on the 20th July 1969, FO Norm Goodall, of 75 Sqn while stationed in Butterworth, became the first RAAF pilot to exceed 1000 flying hours in the Mirage.

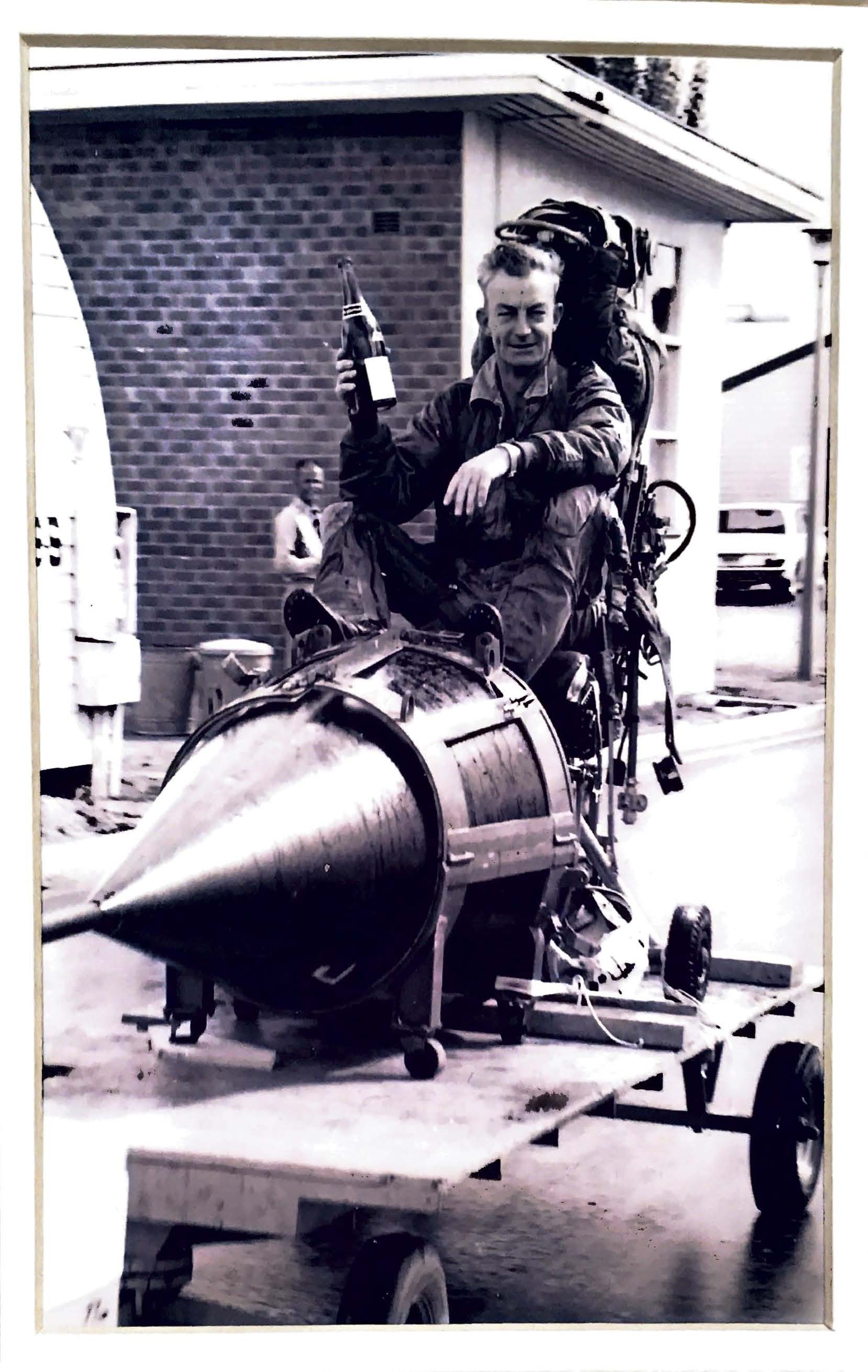

In July 1971 it was my turn. I wasn’t the first to log 1,000 hours in the Mirage but I was the first in 77 Sqn to so do and what a pleasant surprise it was too.

After returning to the Squadron tarmac I was met by a bunch of blokes who had set up a Mirage nose cone on a trolley with a seat and they dragged me round the base on it, after thrusting a bottle of bubbles into my hand to celebrate the event. This was a 77 Squadron thing, other Squadrons didn’t celebrate the milestone this way, I really don't know who the instigator of it was and I guess the same thing happened to other people as a number of other blokes flew many more hours on the bird than me.

But I was the first.

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

In January 1972 I was promoted to Wing Commander, awarded the Air Force Cross and completed No 26 RAAF Staff College Course the same year.

In January 1973 I took up an appointment within, the Directorate of Aircraft Requirements Air Office Canberra, as Aircraft Requirements (Weapons). The position entailed the initiation, and management, of RAAF weapon projects. During this period, I completed a Defence Systems Management Course. I also went to Switzerland as the RAAF representative at an International Conference on the Geneva Conventions that had been convened by the International Red Cross. In January 1976, after completing a Jet refresher course at East Sale, I was appointed as the Base Operations Officer at RAAF Williamtown. In January 1977 I resigned from the RAAF and brought a farm outside Maitland. I re-entered the service on 1 July 1981, at the RAAFs request, for six months to form No 26 (City of Newcastle) Active Reserve Squadron as the founding Commanding Officer.

On the 13th of April 2015, No 76 Squadron honoured me by naming a Hawk 127 Lead In Fighter (A27-09) after me. What an honour.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Here I am with the current Commanding Officer, WGCDR Ian Goold, they let me sit in one but wouldn’t give me the keys to let me take her for a spin.

|

||

|

Frustration is trying to find your glasses without your glasses.

|

||

|

From the Cockpit: de Havilland DHC-4 Caribou. Chris Jaensch © Chris Jaensch, 2020. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Chris joined the RAAF as a pilot in 2002 and flew the Caribou between 2005 and 2009. During his 12 years in the RAAF he also captained the CT4, PC9, Hawk Jet and the C130J Hercules including flying on overseas operational deployments. The Caribou would however remain his favourite type due to the hands on flying it involved. Without an autopilot or weather radar, pilots were always kept busy going from A to B. Another advantage of flying an unpressurised aircraft was the ability to fly at low level along some tropical beach with a window open and an arm hanging out imitating superman! He hopes the following gives some idea of what it was like to operate the mighty “Bou” or "Gravel Truck" as it was affectionately called.

“A typical Caribou crew consisted of a Captain, Co-pilot and Flight Engineer, who doubled as the Loadmaster and Aircraft Technician. Every Flight Engineer had to have previous experience as a technician on the aircraft. Longer trips would usually involve taking additional "techos" for the ever-likely breakdowns that would occur! The Flight Engineer would stand between the elevated pilot seats for take-off and landing and sit in the cargo area for the majority of flight.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Excellent visibility is available to both pilots and the engine controls are located in the overhead console similar to a Twin Otter. Left to right are the Throttles, Props and Mixtures (which have 3 detents, Auto Rich, Auto Lean and Idle Cut-Off). Further aft in the roof console are the Ignition/Magneto Switches and Carb Heat controls. Flying around with your hands hanging from the throttles sounds strange but is more comfortable and intuitive than one may think. Mounting the engine controls on the overhead console requires less complex rigging in a high wing aircraft for cables to go to the engines and it frees up space between the pilots, which in the case of the Caribou is utilised for a slide out "radio boat" (console). This console houses the communication radios (2 VHF, 1 HF & 1 UHF) and navigation receivers (ILS, VOR, TACAN, NDB & DME). A basic Trimble GPS was also fitted in the 90's. To the Left of the Captain's leg on the sidewall is a vertically mounted hydraulic nose wheel steering tiller/wheel which is used for taxiing and steering on take-off and landing until the rudder becomes effective above 40 knots.

Engine start switches are located in front of the Captain's left knee and there are 3 toggle switches arranged vertically labelled START, VIB and PRIME. The Caribou has the advantage of having a starter motor that is designed to slip if any resistance is incurred in the event of a hydraulic lock so there is no need to pull the blades through by hand prior to engine start. The right engine is started first by pushing the start toggle switch to the right and after turning through 15 blades (or 6 on a warm engine) the Captain calls "contact". At this point the VIB and Prime switches are also pushed right and the co-pilot moves the ignition switch to BOTH. After the engine achieves approximately 600 RPM the Starter and VIB switches are released and 1000 RPM is maintained using the primer only.

Once all parameters and no fire lights are illuminated the co-pilot moves the Mixture to Auto Rich and the primer can be released. Sounds easy hey? Not so easy on a hot engine! A couple minutes later hopefully both the Pratt and Whitney R2000s will be purring away happily with the temperatures in the green ready for engine run ups.

Brakes are checked when taxiing out and the propeller reverse is checked for correct operation (unusual to be fitted on a piston aircraft). This is accomplished by pushing the throttles up in to the roof and then pulling backwards. Two blue lights annunciate on the instrument panel to confirm that the propellers have moved into reverse pitch.

Run ups are fairly conventional but like any radial engine all movements with the throttles should be made as smoothly as possible. Props are checked and cycled at 1900 RPM and the ignition check is carried out at static manifold pressure (roughly 30in at sea level). Because the propellers are not governing at this power it is not only a check of the magnetos but also general engine health. The RPM should be within 50 RPM of that placarded (around 2200 RPM), obtained from initial test flight data.

After engine run ups the before take-off checklist calls for flaps to be set anywhere from O to 25 deg. The flap lever is also located in the overhead console behind the engine controls. An indicator instrument panel indicates actual flap position.

A minimum length STOL take-off uses 25 deg flap with a rotate speed of 63 knots at a MTOW of 28,500 lbs. The aircraft can get airborne well below 60 knots but 63 knots is used as it coincides with the minimum VMCA speed (Vmca is defined as the minimum speed, whilst in the air, that directional control can be maintained with one engine inoperative [critical engine on two engine aircraft], operating engine(s) at takeoff power and a maximum of 5 degrees of bank towards the good engine(s)). The take-off roll only takes around 8 seconds so this is one phase of flight that one needs to be thoroughly prepared for.

30" of MAP (Manifold Pressure) is set on the brakes and once released

full power is advanced slowly to 50in giving 2700 RPM. [The manifold

pressure gauge is an engine instrument typically used in piston aircraft

engines to measure the suction pressure inside the induction system of

an

As altitude is gained the throttles need to continually be pushed further forward to achieve 35in as the single speed supercharger loses efficiency. Typical cruise altitude is 9000-10,000 ft using a power setting from the flight manual that equates to 700 brake hp, usually around 31in and 1900 RPM. Below 750 hp, an auto lean mixture can be selected. This results in an indicated cruise speed of around 120 KIAS (Indicated Airspeed) or 140 KTAS (True Airspeed) [True airspeed is the speed of the aircraft relative to the air it's flying through. As you climb, true airspeed is higher than your indicated airspeed. Because of that, indicated airspeed will be less than true airspeed.] using 600 lbs/hour of decomposed dinosaurs. This gives good endurance with a max fuel capacity of just over 4800 lbs but you are not going anywhere too fast. The good news is there is a spacious area down the back to lie down and a "relief tube" at the back of the aircraft for one to empty their bladder. This goes straight overboard via a drain pipe (known throughout the squadron as the piss-aphone) and Flight Engineers were known to use a dirty tactic of relieving their bladder when flying in formation directly in front of the following aircraft! The Flight Engineers always tried to stay one step ahead of the pilots and often succeeded!

All primary flight controls utilise cables and the flaps are powered by a single hydraulic jack. Elevator forces are quite light at all air speeds and a manual trim wheel is located on the right side of the Captains seat. I understand that electric trim was not considered for elevator in the event of a trim runaway. A rudder trim wheel is located behind the engine controls and an electric aileron trim provided on both pilots' yokes. Rudder forces again are quite light and remains very effective at low air speeds which enables such a low VMCA. Because of the high positioning of the rudder relative to the aircraft axis the flight manual warns that a rapid application of full rudder at low airspeed can result in an initial roll OPPOSITE to what one would normally expect. Aileron forces are very manageable up until 120 knots where above this speed they get quite heavy.

The Caribou is a very manoeuvrable aircraft, given its vast size. When flying into narrow valleys in Papua New Guinea a "precautionary" configuration of flap 15 could be used, which at around 80 knots enabled better visibility with a slightly nose down attitude and tighter turn radius to exit the valley if bad weather lay ahead. Large wing overs could also be flown which were not only fun but also an effective means of losing altitude after dispatching paratroopers from the rear ramp. Cargo packages ranging from light cardboard "heliboxes" to "A22" loads up to 2200 lb in weight could be airdropped from various altitudes. After being pushed off on temporary rollers attached to the floor, their parachutes would be pulled open with cables attached to the roof. LAPES (low altitude parachute extraction system), could deliver loads up to 4000 lbs flying at a height of 3-6 feet off the ground with the landing gear extended

A quick web search will find good videos on this. The tactic was developed by the U.S. for Vietnam where the aircraft could fly accurately into a cleared area and accurately deliver the load extracted with a parachute. This meant the aircraft didn't have to expose itself to ground fire by stopping on landing. One of the risks of this was that the load could get stuck in the cargo bay with the parachute still attached and creating a huge amount of drag. Apparently full power and an airspeed of 74 knots would allow the aircraft to fly away but I am glad I never had to try out this theory!

|

||

|

|

||

|

Above: LAPES run at RAAF Richmond with the parachute about to extract the load. |

||

|

Cruise descents are flown at a power of 28-30in and 1900 RPM giving 140 knots and a leisurely 500fpm rate of descent to minimise shock cooling and for passenger ear comfort in the unpressurised cabin. Under boosting a radial engine can be just as damaging as over boosting so we always planned to use at least 1in per 100 RPM for descents where possible (i.e. at 1900 RPM avoid using less than 19"). Re-join checklists cover some more important items such as selecting Auto Rich mixture.

The circuit is joined at 1000 ft with approximately 26" and 2250 RPM and on downwind the landing gear is extended below its limit speed of 120 knots followed by flap 15 selected below 105 knots. The clock is started abeam the landing threshold and the base turn commenced 30 secs later in nil wind. Power around base is 15-17 inches and setting an attitude to achieve 80-85 knots and 15-20 deg angle of bank. Rolling on to finals for a STOL landing should occur at 500-600 ft AGL on a slope considered much steeper than what most aircraft would fly. Flaps 30 are selected below 85 knots and requires lots of forward pressure to counteract the balloon and a very nose low attitude initially results. Finals checks are then carried out, selecting props full fine (full increase in RAAF speak) and the speed is allowed to slow to maintain a threshold speed of 66 knots at typical weights.

Flap 40 (full flap) was rarely used for landing as it only reduces the approach speed by a couple of knots and makes the aileron forces much heavier. This is due to fact the ailerons also droop with flap extension. Aileron authority on finals at such a slow speed is quite poor and requires quite large manipulations of the controls in turbulent conditions leading to the expression of the pilots looking like they are "wrestling a gorilla ". With so much extra drag from the flaps, large power changes are required to fix airspeed errors quickly. A few knots too fast over the fence on a 350 metre strip in a 12 tonne aeroplane can spoil your day quite quickly! Another side effect of the blown wing is that large power increases also result in a lot more lift so one has to be ready to lower the nose as power is increased otherwise you can also end up quite steep on profile. Being fast over the fence also results in the aircraft flying nose low and potentially hitting the nose wheel first. If you nail the speed correctly the flare is commenced at approximately 30 ft (judged visually) and the big Pratts pulled back to idle achieving full back elevator just as the stick shaker comes on with both mains kissing the hard stuff gently - very satisfying when you get it right!

Once the nose wheel is on the runway both throttles are pushed up into the roof to engage reverse pitch confirming with the 2 blue lights mentioned earlier. The captain then verbalises "two blues, your controls ". The co-pilot now has control of the yoke and the captain transitions their hand to the nose wheel steering tiller and pulls back on the throttles to increase the RPM with reverse pitch. At 30 knots reverse thrust is cancelled to avoid ingesting too much debris. All this happens pretty quickly and you also need to remember to use the brakes as well to achieve minimum stopping distance.

Click HERE to see an example.

Parking and shut down is conventional observing a maximum cylinder head temperature of 180 deg prior to moving the mixtures to Idle Cut-Off.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Above: Tep Tep airfield, PNG. 6,969ft above sea level and 10% slope. Not for the faint hearted!

|

||

|

Single engine performance in the Bou was adequate but not startling. I shut down a few engines as precautionary measures and on test flights but luckily never had any failures at critical moments. Because there was no simulator all practice was carried out in the aircraft using "zero thrust" of 15" and 1500 RPM . The large rudder provided ample control in the event of a failure (providing you were above VMCA) and full power on the live engine would return about 300 fpm rate of climb at MTOW and sea level. Like any radial engine however it did not like to be run at high power for long periods and sometimes even after 5 mins the oil temp on the good engine would be reaching the maximum limit during training requiring it to be throttled back. I would not have liked to have had to rely on one engine for 30 mins at METO climbing out of a valley in PNG on a hot day! Conducting STOL approaches required a committal height of 400 ft single engine to allow for the height loss in the event of cleaning up for a go around.

To fly one of the last radial-engined aircraft in military service was a real adventure and leaves me with some great memories. The biggest highlight for me was conducting Humanitarian Relief missions in Papua New Guinea, flying into some airstrips as high as 7000 ft above sea level with density altitudes approaching 10000 ft. Other strips were only 350 metres long and often with a 12% slope and perched precariously on the edge of a ridge line. In October 2011 I was lucky enough to Captain the first Caribou (A4-210} that HARS acquired on its flight from Oakey to Wollongong. When I lived in Sydney, I flew regularly with HARS, including conducting displays at the 2013 and 2015 Avalon Air Shows, but sadly I no longer live in the region to fly with them. |

||

|

|

||

|

Above: Avalon Airshow 2013. HARS took both Caribous A4-210 & A4-234 from their Albion Park base. This was the first time the Caribou appeared at Avalon since 2009 when it was still in RAAF service.

|

||

|

The Caribou is an incredibly unique aircraft which is adored by those that flew and worked on her. I genuinely hope this iconic aircraft continues to fly with HARS for many years to come and that others out there get the same satisfaction that I do of hearing the roar of the mighty gravel truck at full power, even if we do joke about it being one of the only aircraft that can have a bird strike from behind!”

Caribou A4-199, one of the early Caribous that were delivered to the RAAF back in 1964, is now on display at the main gate to RAAF Townsville. WIN News covered the establishment at the gate, you can see that HERE. Prior to being "restored" this aircraft was involved in a hard landing at the High Range training area and had to be winched back to Townsville by Chinook. You can see that HERE.

Click HERE to see pics of the installation provided by the Aviation Heritage Centre, Townsville..

Chris has produced a wonderful hard cover book featuring the old Caribou – you can see information on the book, and also order a copy from HERE.

.jpg) |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||