|

||||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||||

|

|

||||

|

WRAAF News.

|

||||

|

Contents.

|

||||

|

Olympian achieved several firsts in life and in service.

While several Olympians have worn the uniform of Australia’s Air Force, Doris Carter’s story is particularly inspirational.

From an early age, Doris displayed an athletic ability that set her apart from her peers and she pursued a variety of sports throughout her school years before specialising in high jump. She was selected to represent Australia at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and became the first Australian female track-and-field athlete to reach an Olympic final.

Despite carrying an injury into the final, she pushed on to finish just outside the medal placings.

Sadly, the onset of World War II curtailed any further Olympic dreams she may have held – but, as one door closed, another opened.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

In 1942, at the height of the war, Doris joined the Women’s Australian Auxiliary Air Force (WAAAF). Three years later she was chosen to lead the WAAAF contingent in the Victory March in London.

Though she entered civilian life not long after the end of the war, this was not to last. In 1951, she was called up to serve as the first director of the newly established Women’s Royal Australian Air Force (WRAAF) with the rank of Wing Officer. Her outstanding leadership helped shape the WRAAF, which was recognised with the awarding of the Order of the British Empire.

But even in retirement, Doris Carter’s firsts kept coming. In 1996, at age 84, she became the first woman to lead the Melbourne Anzac Day March, sharing the role with Air Commodore Keith Parsons.

Doris Carter, a tireless contributor to any cause she took on, passed away in 1999.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

The WAAAF.

During WW2, the WAAAF was the largest of the three women's services. By the end of the war, about 27,000 women had enlisted. Women were posted to bases throughout Australia, but were never permitted to serve overseas, or in combat roles. Against all expectations, the WAAAF were ‘rapidly transformed from a motley collection of young women from different backgrounds (be it country or town) into an efficient, disciplined body, able to carry out orders without confusion.’

The Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) was formed in March 1941 after considerable lobbying by women keen to serve and by the Chief of the Air Staff who wanted to release male personnel serving in Australia for service overseas. It was disbanded in December 1947. A new Australian women's air force was formed in July 1950 and in November became the Women's Royal Australian Air Force (WRAAF). The WRAAF was disbanded in the early 1980s and female personnel were absorbed into the mainstream RAAF. Australia's first female air force pilots graduated in 1988 and today, every role in the Air Force is open to women.

The following photos are from the State library of Victoria.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Shirley Beckett was the first girl in the Commonwealth to be sworn in to the W.A.A.A.F. The oath was administered by Pilot Officer Taylor at No. 1 recruiting depot Melbourne.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Alma Warren and Dorothy Heitsch, working on an aircraft engine.

|

||||

|

The WAAAF was the first military organisation in Australia for women which focused on skills other than tending the sick or injured. The establishment of the WAAAF paved the way for similar organisations in Navy and Army. Some women joined the WAAAF because they saw it as their patriotic duty, others to see the world and some to escape the social confines of life at home with the men away. Critics viewed the new organisation as a radical move and at least one national leader, the Minister for Defence, Harold C. Thorby, (right) opposed it. 'Aviation takes women out of their natural environment, the home and the training of the family,' he said.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

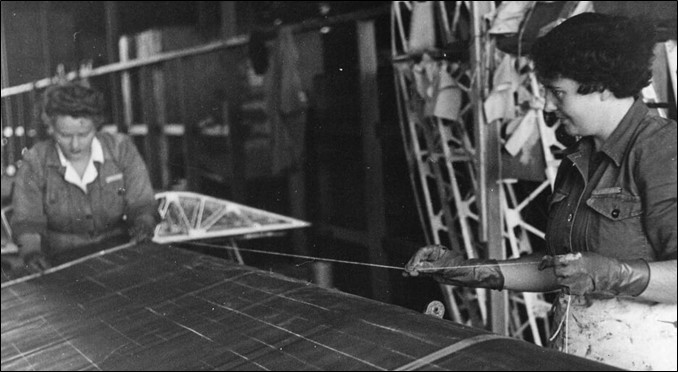

Beryl McNeill and Nell Kinkaid, stretching fabric over the aileron of a Catalina flying boat.

|

||||

|

These fabric workers knew to an inch the amount of material required to cover their aircraft.

It's no exaggeration to say that military life came as shock to some women: they had trouble adjusting. The WAAAF was designed and run as an efficient military organisation. In all areas, except pay and entitlements, women were treated the same as men in the Royal Australian Air Force. Pay and conditions were vastly different to men, women were only paid a percentage of the equivalent male wage and married women were not allowed to remain in the WAAAF.

There have been numerous stories written about the lives of women in the WAAAF. Many are both entertaining and informative and provide a clearer picture of what the women went through. One 18-year-old recruit to the WAAAF was handed a hessian bag and told to use a pitchfork to fill it with straw for her bed and, thinking bigger is better, she piled as much straw into that bag as possible. After a restless and somewhat painful night, she removed a good portion of the straw. Another woman, posted to No. 1 Fighter Squadron, located in a poorly ventilated unused train tunnel in Sydney City, received a rare treat courtesy of the American Allies. She was given a five-course meal including doughnuts for breakfast, lunch and dinner - a far cry from the usual rations provided by the WAAAF.

Another WAAAF member complained of the apparent injustice of the authorities running Air Raid drills only when it was raining.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Corporal Dorothy Trewin checking the instruments in the cockpit of a bomber aircraft.

|

||||

|

As the strength of the WAAAF increased, its members began to invade the traditional male dominated areas. Women of the WAAAF worked in more than 70 different musterings across the entire organisation, including as truck drivers, signallers, electricians and anti-gas instructors. They also worked on machine guns, in repair shops, in mess rooms, in hospitals and in parachute sections. They worked wherever they were needed.

The end of the WAAAF.

With the end of World War II, the WAAAF was progressively disbanded, with the last members demobilised in July 1947. The quiet dignity with which the WAAAF served won praise and admiration, not just from the men of the Air Force, but from the entire community. In 1950 their skill, abilities and contribution were recognised in the formation of a permanent women's Air Force.

Some 27,000 women served with the WAAAF and many still consider their time in the Force as a highlight of their lives.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

WAAAF armorers, Margaret Deal and Rosemary Kemp, installing a Vickers machine gun into an aircraft.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Ivy Benson and Betty Ali from Victoria and Dulcie Noble from South Australia folding parachutes.

These women trained for several months, learning how to air, inspect and maintain the parachutes. After their final course, lasting two months, they could prepare a parachute ready for use in 30 minutes. They worked under enormous pressure – a man’s life literally depended on their precision and care! Each parachute had to be aired and given a complete overhaul every two months.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Esme Coase, Joyce Gallen and Dorothy McIntosh, load practice rockets onto a Beaufighter.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Nola Walton, from Brighton in Victoria

Women were a crucial part of the RAAF communications system. They staffed Radio Direction Finding Stations to guide aircraft home, large numbers were radio-telephone operators and most of the telephone and teleprinter operators were WAAAF. The coastline of Australia was screened by radar, keeping operators on duty 24 hours per day.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Women in the WAAAF working in a large telegraphic operating room.

The WAAAF was an Australian wartime success story.

|

||||

|

A quiet man is a thinking man. A quiet woman is usually mad at you

|

||||

|

Shannan Forrest.

Ever since Shannan Forrest was young, she knew she wanted to travel the world as an aeronautical engineer in the Air Force. Growing up as a ‘RAAF brat’ with her father in the Air Force, now-Wing Commander Forrest can recall going along to RAAF Base Laverton to watch the Air Force Cadets fly gliders every weekend. Even though she wasn’t in cadets, she would often volunteer to get involved in the glider maintenance.

“My hands were small enough to fit in the holes and I helped re-skin a wooden fabric glider,” she said. “It was interesting and fun, but it was probably my work experience in high school with a local contractor at Avalon Airport building the F/A-18 Hornet aircraft which really helped me make a final decision to become an engineer. The company also designed and built the Nomad aircraft and I helped them complete the mathematics required to keep the aircraft flying longer.”

Declining an engineering cadetship with the company, she applied and was accepted into the Australian Defence Force Academy and moved to Canberra to study a Bachelor of Engineering – Aerospace. After four years of study, her first posting was to Weapons Systems Support Flight at RAAF Base Williamtown, where the team was making their own software patches for the F/A-18 Hornets. “Our team got to design the oxygen delivery warning system and a number of other testing systems for the aircraft, which was really exciting and important,” Wing Commander Forrest said.

She then moved to No. 3 Squadron at RAAF Williamtown, where she spent two years as the maintenance officer.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Senior Engineering Officer of Number 2 Operation Conversion Unit, Squadron Leader Shannan Forrest (left) and Armament Officer, Flying Officer Stephanie Hall from Number 1 Squadron discuss engineering characteristics of the F/A-18A Hornet engine exhausts. (2015)

|

||||

|

She investigated the operation of the undercarriage doors for the Hornets. “My team redesigned how the doors were fitted, which was then rolled out across the fleet, including in the United States," she said. But it was her next move back to Laverton, Victoria, which she said was one of her most exciting postings. Wing Commander Forrest and her team got to test the fatigue life of the F/A-18 aircraft to see how many hours they could fly before the airframe would break. “We tested the tail section of the aircraft, we would run this complex, world-leading, test rig and check for cracking each day, and if it cracked, we would design the repair system for it. The whole idea was to keep testing until it would break.”

Wing Commander Forrest’s career has since involved multiple overseas postings, where she has had roles in safety, contract management, logistics and leadership, including an eight-month deployment as a commanding officer in the Middle East in 2020. “Being an engineer isn’t just about design. You learn to break down complex problems into simple parts that you can manage and solve in new ways,” she said. “In the Air Force as an aeronautical engineer, you can work in ground roles, flying roles, logistics and acquisition. There are so many opportunities, places to travel and ways to challenge yourself.”

Get together.

Vici Goninan said “I caught up with these girls recently. We were planning on a get together in Canberra for the 70th/100th anniversary which would’ve been fabulous but as that wasn’t possible, by pure luck we were all in SA at the same time. Timing is everything!

They were at Williamtown together between 1976-1981.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

L-R: Rose Gibson, Connie Leone, Vici Goninan, Teresa Fox, Robyn Smith.

|

||||

|

History of the Women’s Royal Australian Air Force.

Even in the Nineties we must learn never to take things for granted; we should always wonder how things evolved and more pertinently, how we reached the stage we are at present. This is particularly so when noting the current career opportunities for the female members of the RAAF.

There was a time, not so long ago, when female officers were only employed as Officers in Charge of WRAAF (OIC WRAAF) and airwomen were only recruited into the more traditional female based musterings such as clerical, steward and supply. The Service female of the Nineties has the world at her feet; she can do almost anything, go anywhere and aim for senior ranks. Nowadays female pilots, air traffic controllers, engineers, fire-fighters, police dog handlers, engine fitters, and musicians (to name just a few) are happily employed in musterings which were, until a few years ago, exclusively male domains.

Have you ever stopped to wonder just how this all came about? The conditions of service, employment across the board and equal pay, now accepted as the norm by female members, were all the result of years of hard work, a dedicated belief in the knowledge that women can do anything and a tenacity to fight to the end to ensure that they were given the opportunity.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

The first female Air Force pilots were Flight Lieutenant Robyn Williams and Officer Cadet Deborah Hicks.

|

||||

|

The hierarchy of the WRAAF did just that and thanks to their efforts the female service members of today reap the benefits. Ironically, the fight was so hard and they were so brow-beaten that most of them left before they could take advantage of the new conditions.

Now it is timely to write the history of this struggle so that those of you who may never have even heard of the WRAAF will understand what those members did to ensure that the modern female airwoman and officer could be employed in such a variety of categories and musterings and receive a commensurate wage for their efforts.

The Australian airwoman came into being during World War 2 with the creation in 1941 of the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF). Approval was given on 4 February 1941 to enrol 320 women who were employed in 73 different musterings as diverse as Fabric Worker to Photographer, Clerk to Cook and Meteorological Charter to Motor Transport Driver. During the war years, the WAAAF proved themselves and won high praise. For those women who had previously stayed at home this war-time interlude was far more exciting than their humdrum, domestic life and to this day they still regularly attend WAAAF Reunions throughout Australia.

Their Fiftieth Anniversary was celebrated at RAAF Williams in 1991 and over 1000 ex-members attended the two day celebrations. Unlike most British Commonwealth countries, Australia decided at the end of the 1939-45 war, to disband all her women’s services except the nursing services, but less than three years after the last of the WAAAF were demobilised in 1947 the Government reintroduced a Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF).

In July 1950, Cabinet approved the re-establishment of a women’s air force in principle and in August came recognition that women were essential components of the armed forces, in peace and in war. No longer an Auxiliary, the proposed new Service was regarded as a Branch of the PAF until November 1950, when his Majesty, King George V1, approved the adoption of the title ‘Women’s Royal Australian Air Force’ (WRAAF).

Conditions of service for WRAAF were similar to those for airmen but an airwoman’s pay was considerably less than the male rate in the early days and remained so until 1977 when at last equal pay was approved. From the beginning the WRAAF was part of the Permanent Air Force, but quite distinct from the RAAF; WRAAF Officers well recall that difference as they had very limited command and control over airmen. Over the next twenty years there were some additions to the jobs airwomen could do and the geographical areas in which they could be employed, such as Townsville and Darwin, but essentially they were still confined to tasks that were very closely aligned to jobs taken by women in the community generally and were still limited to mainland Australia.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Other milestones were reached slowly with the next major achievement not occurring until 1972 with the promotion of three WRAAF officers against three RAAF posts. A change in policy in 1969 permitted a member of the WRAAF to continue serving after marriage if she elected before marriage to do so and undertook to meet in full the normal service requirements expected of unmarried members. In 1974 pregnant women were permitted to remain in the service; a great break through after the years of sending pregnant, single WRAAF members to homes for unmarried mothers and then discharging them!

In 1975 after public pressure forced a review of servicewomen’s employment there were substantial changes. Many non-traditional areas were opened up to women. That year saw the first female engineering cadet accepted, the first female radio technician and the first female clerk financial accounts enlisted. (1975 was the same year that women were allowed to wear sleeper or stud earrings in uniform – an incongruous contrast of achievements). The way was now open for women to be recruited directly into the RAAF.

The first of these ladies was an education officer, appointed in February 1976 closely followed by an accountant, administrative officers, air traffic control and equipment officers. Finally in 1977 all the officers and airwomen in the WRAAF (with the exception of two officers who elected to remain and retire at 50) were transferred to the RAAF. Our thanks go to those women with a vision, who worked hard, sat on interminable committees, fought endless battles against the Victorian attitudes with the Establishment, wrote copious service papers and although it was too late for them to benefit from the change, finally won the day and all women were transferred into the RAAF with a commensurate wage which reflected their true worth.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Samantha Luck was the first female to conduct Aircraft Security Operations in the Middle East, in March 2015.

|

||||

|

At the time of transfer to the RAAF, the type of employment for airwomen was wide ranging, however, initially the RAAF classed all air crew positions, along with ground defence, disciplinary and marine craft musterings, as combat positions plus the positions in certain operational squadrons, together with the support element which would deploy, as combat related. Over the next six years there was only one small but significant change which occurred in 1987 with the recruitment of the first female pilots, however, like female radio technicians who could then not serve in an operational squadron, our female pilots were also limited to non-combatant aircraft, such as VIP aircraft.

In May 1990, the Australian Defence Force changed the policy towards employment of women by lifting the caveat on combat-related positions. For airwomen, this change meant that almost all positions were opened to women in equal competition with the men; though the surface finisher and electroplater musterings are closed for health reasons associated with embryo-toxicity. A major review of the ADF policy on the employment of women was completed in 1992. The focus was to determine whether women should continue to be excluded from combat and combat-related duties as currently provided for under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984. The outcome of this review was that on 18 December 1992 the Government removed the restrictions on women serving in all combat-related employment and retained employment exclusions only for duties that can be classified as Direct Combat. This will only effect the Ground Defence officer category and the airfield defence guard mustering in the RAAF; women are now eligible for flying duties on all ADF aircraft.

For the women of the Royal Australia Air Force of the Nineties the sky is the limit; with ability and ambition, she can aspire to the highest levels in her chosen field.

|

||||

|

WRAAF Quarters – Fairbairn.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Shirley McLaren

Ex WRAAF Shirley McLaren received her OAM on Australia Day 2021, from the GG in recognition of her services to veterans and their families and to the community.

|

||||

|

||||

|

Shirley was on the first course and is responsible for WRAAF getting the service medal. Because we were discharged to get married we were not able to get one for many years. Shirley advocated for many years. Her OAM is truly justified.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

WRAAF Rookies Course 294 (Basham's Beauts) Sept 1982.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Back Row L-R: Diana Cooper, Tanya Beardsell, Sharlene Neller, Desiree Bowman, Gaye Neilsen, Darlene Law Middle Row L-R: Sandra Copelin, Leonie Lamont, CPL Dave Basham, Heather White, Elizabeth Lax, Sharon Bright Front Row L-R: Peta Welfare, Carol Allan, June King, Diane James, Debbie Schuman, Kerryn Sandles

|

||||

|

32Comms Nov 1982

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Standing L-R: Andrew Yarnold, Cynthia Browne, Desiree Bowman, Leonie Lamont, SGT Dave Macky, Seated L-R: Diane James, Carol Allan, Peta Welfare, Kerryn Sandles.

|

||||

|

WRAAF Rookies Course 280 28 Sept 1981 - 04 Nov 1981 Sent to us by Margaret Tuckwell.

|

||||

|

||||

|

WRAAF Rookies Course 281 28 Sept 1981 - 04 Nov 1981 Sent to us by Margaret Tuckwell.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||||

.jpg)

.jpg)