|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

||

|

My Story |

||

|

William Steele.

(H)appy Days, Wagga.

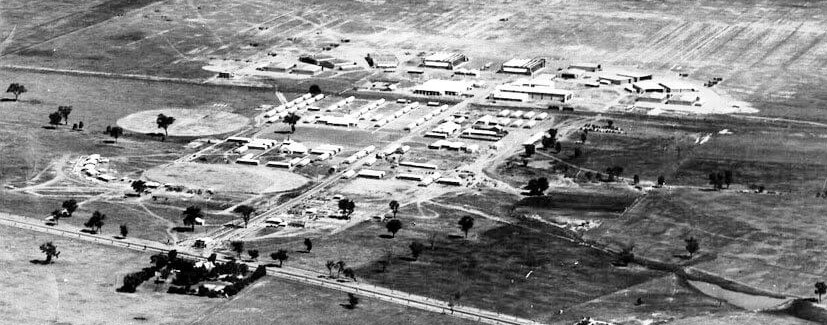

From a strategic point of view Wagga Wagga was an ideal site for an Air Force Training School being approximately half way between Melbourne and Sydney (367 km and 380 km) but from a weather point of view it was less than ideal. Temperatures in summer reached the mid-forties and in Winter they dropped to a few degrees below freezing point.

|

||

|

|

||

|

This you all know. But for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Intakes the start off was not easy. Facilities were still temporary wartime buildings. Sleeping quarters were in recently lined huts but not the ablutions. The latrines were in the form of stalls in an open-ended corrugated iron cow shed and the ablution hut was a similar structure. The First and Second Intakes were quartered in half timber, half fibro-cement huts with a corrugated iron roof. Only the Hut Supervisor, Wally Thomas in my hut, had a wall plug for an electric heater in his room at the top corner of the hut. Of little consolation for the cold weather was a bedside mat, originally intended for Pakistani Apprentices as a prayer mat, which could be used as a blanket to supplement the three on issue. We slept on a hard horsehair mattress.

Our beds were all that the Stores Depot could rake up, not only the hospital type with head and foot but folding steel camp beds which could be easily let down to floor level, with the occupant included, by raiding parties from other huts. Air Force Regulations required that all personnel must be clean shaven. No exception was stipulated for Apprentices even though some of us had not even thought of shaving. On parade one morning I was asked by the Drill Instructor if I had shaved. When I said “No sergeant” he replied “Well, see that you are clean shaven by tomorrow morning”. My dilemma was that I had only a bit of “bum fluff” on my chin and I was reluctant to start shaving. The advice from my room mates was to burn it off with a lighted match. This I did, and on parade the next morning I was again asked if I had shaved. “Yes sergeant” I replied and to that he said with his face close to mine “Well, the next time stay a bit more closer to the razor”.

At the first opportunity I washed my newly issued black socks under the shower and hung them out to dry on the clothes line alongside my hut. When I went to retrieve them later I found that they had been substituted by a pair of similar issue but well worn socks. The Anzacs, who with six months experience had not yet learned to use their mending kit (known as a housewife), were just waiting for a re-supply at no cost. I quickly found that the solution was to hang my newly washed socks on the wire netting on the underside of the bed.

A swimming pool didn't exist on the base and I don't remember ever having the occasion to go swimming in Wagga, however, someone discovered a dam on a nearby property and I was able to join a small group of Appies for a dip. Following this episode we were told to discontinue this practice because the owner of the property had complained that his sheep were reluctant to drink the water from the dam which we had polluted. I really think he was afraid that we would go back there to catch yabbies.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Maggots were often served with cold meat dishes due to the difficulty of keeping the blowflies out of the cook house in that fly infested sheep raising district, even with double flyscreen doors. Any complaint was rebuffed by the Orderly Officer's reply of “Don't let the others hear you or they'll all want some”. Another ready-made reply was for the blowfly in the mug of tea who was excused with “Don't worry, he won't drink much”. The meals couldn't have been too bad because when all had been fed and the Duty Cook cried out “Anymore for any more?” At this summons only the quickest could rejoin the queue for seconds (backups).

We had two cooks to feed us. One was spick and span in his white bleached and starched working uniform while the other was the opposite in his dress.-.and also his habits. On my first weekend mess duty I not only became aware of his dress but also of two queer habits. One was that he put all three of his dishes on to the same plate to eat saying “It all finishes up in the same place”. The other was that he smoked while cooking, probably because he was a chronic smoker. I was amazed to see him standing over a pot of brew with a cigarette in his mouth and the ash getting longer and longer. He obviously did this so as to keep on smoking while working and the trick was, as I later found out, to push a needle down the whole length of the cigarette to prevent the ash from falling off as it burns.

Occasional night raids were made on the Airmen's Mess, through an accidentally unlocked window, not only to satisfy the ever-present pangs of hunger (hollow leg condition) but to enjoy doing something against the rules. On the only occasion that I took part in a raid one of the party put his dirty stockinged foot in a tray of custard on the floor under the unlocked window we used for entry. I took part no more in this type of escapade and preferred a hot dog at the mobile tuck shop parked beside the post office.

The name of the post office, Allonville, was the name of the property taken over by the Government in 1939 to establish the Air Force Station. Many evenings I spent on it's half-enclosed verandah to await a reverse-charge call to my parents in Melbourne.

Sport was very popular with the Apprentices and included football, cricket, swimming, boxing and even tennis. Maybe playing tennis owed some of its popularity due to the fact that F/Lt Tom Cusack's pretty daughter also played this sport on the station's court. Sports were played on Wednesday afternoon. It was a parade and therefore had to be attended. After roll-call we were all marched-off to our chosen sporting sites. For those not having selected a sport, like me, Sgt. “Granny” Laybutt had chosen jogging for us. One afternoon, I decided to skip the long jog around the camp perimeter and I set myself into my hut's broom locker (a parachute locker) with a Ginger Meggs' comic book. Unfortunately the Orderly Officer accompanied by the Orderly Sargeant were making their routine hut inspection, which included a locker inspection, to check on their cleanliness and tidiness. On opening my locker, the officer immediately and naturally asked what I was doing there. I immediately and naturally replied “Reading a comic Sir”. A bit taken back by my reply but still able to assert his discipline he sternly said. “For being insubordinate as well as being absent from parade you will put on two charges”.

I was sentenced to 14 days confinement to barracks (CB). This punishment varies from base to base. At Forest Hill you had to wake up early to put on your service uniform (full dress), walk to the guard house to sign the report book, walk back to the hut to change into working uniform (overalls), go to the mess for breakfast and then go on stand-to parade to carry on with the normal working procedure. The same steps were adopted after stand-down and again before lights out and the set-up for the weekend was that the normal daily procedure was substituted by extra duties. For this task I was assigned to the mess. My duties were serving dishes, washing up (pot bashing), scrubbing the floors and peeling potatoes.... by hand.

The following weekend I was assigned to the hospital. This turned out to be a cushy job which consisted of polishing the floors with an electric polisher, emptying the patient's bed pans and making and serving tea, coffee or cocoa. Naturally I also participated in tea breaks and both meal breaks. The Nursing Sister was very pleased with my work, especially the shiny linoleum floors, and this was to help me when I was hospitalized at No. 6 Base Hospital Laverton three years later. At that time the Medical Officer at Wagga was WgCdr Frew who specialized in venereal diseases (the pox). Having done a posting to Iwakuni with 77 Sqn he was very keen on the subject of personal hygiene in the genital region. After a lecture on the subject he called on those who had not been circumcised and asked them if they would like to undergo a small operation on their penis. He explained that this operation was not painful and that afterwards we would be given a No Marching Chit and would be excluded from all parades, sporting activities included, for fourteen days. This just suited my “try something new spirit” and I volunteered with five others for the operation.

Shortly after the operation, at 6 Base Hospital Laverton in May 1949, the doctor made his customary round of inspection. At my bedside he examined my appendage and exclaimed “My god Apprentice Steele, that looks more like a Chinese dragon” and the Nursing Sister then nonchalantly applied the appropriate medication. Back at base the No Marching Chit was sorely needed as the head of my penis became sore on contact with my trousers when walking. We all surely presented a very unmilitary sight straggling up to the working area like a gaggle of geese.

No 2 Intake fostered the Armament Fitters, a trade that also involved skills outside the aircraft maintenance field. Our course not only included dismantling, cleaning and re-assembling of small arms, the maintenance of airborne armament but also the management of high explosives. A little lesson on engine starting by propellor swinging on a Tiger Moth, with all the precautions to be observed, was given. On another occasion we learnt to hand crank an inertia starter and wind up the undercarriage of an Oxford Trainer in exchange for a short flight around the camp.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Tumbarumba Railway Line with its RAAF Wagga Wagga Siding traversed the base and was an escape route to get off the camp without permission. Some Appies used this means to go to the Shanty Pub for an illegal bottle of wine given through the back door by the publican for his underage customers. This location is now known as Alfredtown, situated about 5km from Forest Hill. I only went once to this pub because I found that this distance, partly along the railway track where the sleepers are not placed at a comfortable distance for walking, and partly along the Sturt Highway, was not an easy walk. Maybe to get away from the routine of military life or for the spirit of adventure I used this exit to get away from camp and go to Melbourne with three other Appies without a leave pass.

Sneaking out of camp after lights out we hitch-hiked along the Sturt Highway to Uranquinty Railway Station. There we jumped into an open wagon of a freight train heading South for Albury. The trip took hours, with frequent stops for loading and unloading goods. Shortly after our departure from Uranquinty Station we were beginning to feel cold and miserable until the guard who, unbeknown to us, had seen us “jump the rattler” and told us “Hey, you in there! Wouldn't you be better off in the mail van at the end of the train?” Part of the mail van at that time was a compartment with bench seats for persons having to travel outside the regular running times.

We finally got to Albury too late to catch the “Spirit of Progress” to Melbourne. The next train got us to Spencer St. Station in late afternoon and we proceeded to our own homes. To get back to our barracks my mates chose to pay for their return fares, but I still had a want for adventure in my blood and so I chose another way. I therefore presented myself to the Rail Transport Office and declared to the Duty Sergeant that I had shot through from Forest Hill. He said that he would give me a travel warrant for Wagga and added that he was bound to escort me back to there but did not feel like taking the trip away from home. So he told me he would send me alone and he then recommended me to be a good boy and not get up to any more tricks.

Back at the base I was put under guard and later on sentenced to 14 days detention. There were two detention cells in the Guard House (now the museum) and the rule was that one cell was destined to hold either one or three detainees and never two, so that a second cell became necessary in the case of two. Sleeping was on a wooden pallet with two blankets and no mattress. I was marched to the mess for meals in overalls, without headgear and under the escort of two guards. Trying to sleep in the Guard House was a problem due to the abundance of mosquitos which bred in the septic tank situated on the right hand side of the entry gates. This was also a problem for those rostered for guard duty who were given only two hours for sleep every four hours.

To keep me occupied during detention I was given small jobs such as washing the Service Police van, cleaning the toilets and making tea. On another occasion I was told to go with the Service Police to the Post Office in Wagga to pick up the mail. Parking on the roadside near the side door of the Post Office, all three of us got out of the van. One SP stood at the side of the van holding a Thompson .45 Sub-machine Gun and the other, armed with a .38 S&W Revolver, walked with me to the Post Office door. At the door I was told to take the locked bag from the Postal Officer and then I walked back to the van with the SP and we returned to Forest Hill. All these security measures seemed useless when the Postal Officer (unaccompanied) had picked up the mail from the Railway Station on his bicycle after the arrival of the morning train from Melbourne via Albury.

Travelling to Wagga was hard for some Appies who came from remote towns. In a book describing the introduction of the Apprentice Training Scheme it was stated that Apprentices who came from towns in outback Queensland or Western Australia would be flown home on Annual Leave to save time. This was not at the start. I remember that the Western Australians from the 2nd Intake arrived one week after most others because, at that time, the steam locomotive took 4 days from Kalgoorlie to Adelaide. One of these, Stansfield, who came from Laverton W.A. told me it took him one week to get home on his first leave. Another, who I don't recall his name, came from Mt. Isa in Queensland, and I guess he also had the same difficulty in travelling.

As the Appies now numbered nearly 100, the 3 ton service transport was not sufficient for the Apprentice Squadron and we were given a 7½ ton Mack prime mover with a canvas covered trailer which we called the “Hundred Passenger Truck”. This was used to transport us to various sporting events, memorial occasions in Wagga Wagga and also to take the Roman Catholics, about 30, to Mass at the Cathedral. On Anzac Day we would proudly march down the main thoroughfare of Wagga Wagga with our SMLE rifle at the slope, buckles polished with “brasso” and gaiters whitened with “blanco”. On one occasion three other Appies and I were selected to mount the Honour Guard in the Memorial Gardens. Placed on the four angles of the Cenotaph and to the rattle of the drums we would slowly upend our rifles, place the muzzle on our left toe, place our hands on the butt, bow our heads and stand still until replaced.

Shortly after getting in position I felt a small pebble under my left foot and it began to tremble. A little girl standing right in front of me with her mother shouted “Look Mummy his foot's trembling”. Feeling very embarrassed I had to eliminate this tremor also because it was making me nervous. With a few very small movements of my foot so as not to make people aware that I was moving it I managed to eliminate this inconvenience and patiently await the end of my turn. I carried out this Upend Rifle Drill another time at the Wagga Cathedral for Remembrance Day. This time there were no pebbles on the tiled floor.

No 2 Intake fostered the Armament Fitters and our course not only included dismantling, cleaning and re-assembling of all small arms on issue to the RAAF at that time but we had to fire them as well. We fired the S&W Pistol, the SMLE Rifle, the Thompson Sub-machine Gun and the Bren Gun on the 25 yard range under the instructions of Sgt. “Gunny” Gunn. After firing we naturally had a “brass party” consisting of gathering-up all the empty cartridge shells for scrap. Our first taste of demolition work was with a 25lb Practice Bomb in November 1950 under the guidance of F/Sgt Walter Kirby, who sported an “O” half wing of the pre-war aircrew mustering of Observer.

Then we went on to a bigger task of demolishing heaps of aerial illumination flares at 2 Central Reserve at Ettamogah near Albury. We arrived there after breakfast time but nevertheless the cook was pleased to serve us. However, he said, he only had eggs on hand but we had the choice of “ How'dya like 'em done”. Not for nothing did this site get the title of “The Ettamogah Guest House”. The kitchen was bounded on three sides by the officer's, sergeant’s and airmen's messes so that the meals were always the same....more or less! A nice place for a posting I thought, except that, as I was told, personnel were few and extra duties were many.

No airmen's bar for us as the consumption of intoxicating liquors by apprentices on or off duty was prohibited. Unaware of this the driver of the service truck taking the civilian workers back to town would drop us off at the nearest pub and pick us up on the way back. Apprentices were not allowed to smoke before the age of eighteen years and then only with a written permission of their parents. With our miserable pay we couldn't afford to be even moderate smokers and the “makings” and not “tailor mades” were the choice when we could buy them. Cigarette butts were not thrown away but awaited another day when the tobacco could be re-rolled. On one occasion I took the opportunity to slip out of the classroom to have a smoke. While puffing away I was approached by an instructor. “You can't smoke here” he said. Without noting the emphasis on his last word “here”, I replied that I had permission. “But not here” he said. This is a no smoking zone. Now buzz off or I'll put you in”.

With the arrival of the boys to form the 2nd Intake we got a new Sergeant D.I. who answered to the name of Charlie Spencer. He had earned the nick-name of “Shorty” because of his bodily height. I also heard him called “Boots” and I simply thought it was because he always wore brilliantly shone boots. I heard, much later on, another version of this nick-name. For the next practical experience we were taken up in a Lincoln Bomber from Sale. Together with the boys from the 3rd Intake we each dropped a practice bomb on the Ninety Mile Beach to show us the workings of the Norden Bomb Sight.

The rest of the course was uneventful and I concentrated on studying for the final exams and Graduation Day. My marks were average and I was declared proficient.

In November 1950 we had a bivouac to learn bushcraft and camping techniques while still having to carry out normal daily procedures such as stand-to and stand-down parades. Six-man tents were erected, a large mess tent and a partly exposed kitchen completed the site on the Murrumbidgee River.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Passing Out Parade was the routine ceremony on the Main Parade Ground in front of the Airmen's Mess and passing before G/Cpt ”Blacky” Black. The main difference was that we passed out in blues instead of khaki drabs. At the Graduation Dinner G/Cpt Black gave me a mention, amongst all the others who had distinguished themselves in sport or trade proficiencies, that I had straightened myself out and had become a worthy airman. For the Graduation Ceremony my mother Rose came to Wagga together with her sister Stella. During the Ball that evening in the Kyeamba Smith Hall we were approached at our table by Sgt Spencer who, after being presented to my mother and my aunt, asked my aunt for a dance. After the dance I told my aunt that his nickname was “Shorty” but he was also called “Boots! That's strange” she said “Because in the Army (where she worked in the Army Canteen Services) it means a crawler or otherwise somebody who is so far up himself you can only see his boots”.

Graduation Dinner Celebrations went on until the early hours of the morning. Thanks to the plentiful supply of beer made available with our monetary contribution by Frank “Cros” Crossley it became necessary to return to the hall, not only for cleaning up, but also to empty the barrels of the remaining beer. My posting was to 1AD Laverton along with the other Victorians, a Tasmanian and one from Deniliquin in New South Wales. We went back to our habitual wooden huts because the brick sleeping quarters were occupied by the Anzacs. In the Armament Section I was given, together with a classmate, McAlpine, the task of degreasing a stock of .5 Brownings before re-brunatizing and re-greasing them for further storage. In the act of lighting the oil-burner of the degreasing bath we gave it too much compressed air. This resulted in a small explosion which blew us back a few paces and burnt our eyebrows and the hair on our forehead to make us the laughing stock of our mates for a few days.

Queuing-up for meals was a problem at Laverton as I was an habitual latecomer. The airmen's line seemed never-ending while that of the airwomen was short. At breakfast one morning I arrived late with “Paddy” Lawler, a mate from the Anzacs, to discover that the milk had run-out. At that, we both proceeded to the other side of the mess where another milk can was available. After dosing our plate of cereals with milk we were confronted by a WRAAF NCO who indignantly said to us “This is WRAAF's milk”. Paddy's spontaneous reply was “All the same to us Miss” and we proceeded back to our tables to eat our cereals with cow's milk.

Another task was the testing of the gun turrets on the Lincoln Bomber. This was done during flight tests of the aircraft after major overhaul carried out by the Government Aircraft Factory at Fishermen's Bend. Flying over Port Philip Bay and blazing away at nothing with two 20mm Hispano Suiza Machine Guns of the mid-upper turret was the most exhilarating experience in my career.

Early in December 1951 I decided to go to Wagga, on my new 350cc AJS motorcycle, for the 3rd Intake Passing-out Parade and meet up with old mates. At Tallarook the old two-lane Hume Highway passed to the other side of the Melbourne to Albury Railway Line in a sharp left turn. At this point I collided with the semi-trailer of a truck going South and I was thrown off my motorcycle and suffered injuries to my right arm. Upon the arrival of a doctor he said he could not treat military personnel but would call an ambulance from Puckapunyal Military Base.

On arrival of a WWII army ambulance after about 15 minutes I was helped by the driver to stand up and was told “I'll put you on the floor so you won't dirty the stretcher with blood”. I was then taken to the Base Hospital and kindly treated by the Nursing Sisters for a bone fracture and put back in the ambulance, this time next to the driver. Then we headed down the Hume Hwy. to Laverton and along Sydney Rd., weaving amongst the trams and motor vehicles with the siren blaring and the driver in ecstasy.

At 6 RAAF Hospital my fractured arm was put in plaster and I was hospitalized. On 20th December I was due for an operation on my arm and the previous evening Frank Crossling and Jordan Rigby, who had just returned from removing .5 Brownings from Liberator Bombers at Tocumwal, brought me a bottle of beer for my birthday. On the operating table next morning I felt something was going wrong while inhaling the anaesthetic (ether). After some encouragement to keep on breathing from the anaesthetist I became unconscious. When I woke up in my hospital bed I asked the medical orderly what had happened while taking the anaesthetic. He replied “You vomited” and I answered “Yeah, ether makes me sick”. “That was no ether, that was pure beer and the M.O. is going to put you on a charge”.

I never went on a charge. I just idled away my time in the surgical ward waiting for my broken radius bone to heal. It never did heal and so at the third operation a metal strip was used to unite the two pieces of bone. Four months had passed and I was extremely bored with hospital routine and having nothing to do. One morning while passing the ward housing the patients with sexually transmitted diseases (commonly called “the pox”) I met the nursing sister who had praised my work while doing extra duties at Forest Hill Base Hospital. I asked her if she could find something for me to do and she replied that she would ask the M.O. for permission. The next morning she told me that I could help in the X-ray Section. I quickly picked up my drabs from the hospital store, changed from pyjamas and presented myself to the two NCO Technicians. I was shown how to develop negatives and also told that I would sometimes have to take them to Melbourne for a report by a specialist.

At that time the WRAAF had just been formed and many airwomen were arriving for chest x-rays. This meant they would have to expose their breasts and, so as to not cause them any embarrassment (women were more timid in those days), I would be closed in the darkroom. This precaution did not worry me at all as my main thought was beer not boobs after being on the water wagon for months. This situation was resolved in two ways. The first was when going to the City with x-rays I would usually have time for a couple of glasses before returning to Laverton by service transport. The second was that, being in uniform instead of pyjamas I could now visit the Airmen's Bar.

All good things come to an end and I was finally posted from 6RHOS to LAVD for discharge on 30.04.1952 as “Medically unfit for further service”.

I will finish my story at the Australian Consulate in Milan where I again met Barry Pearman from the 2nd Intake Engine Fitters Course who was at the Aermacchi factory for the acceptance of the MB326 Trainer. I asked him about the motorcycle that I had sold to him after my accident in December 1951 and he said that he still had it.

|

||

|

An Irish ex seaman dies with instructions to be buried at sea. His wife went to Seamus O'Malley the undertaker who informs her that he'd never done a burial at sea, but he had friends who would help him out. He later told her to be at the quayside at 10-00 the following day. On arrival, she found a 30ft rowing boat at the quayside complete with 10 strong men at the oars and her husband's coffin on a central platform.

She steps aboard and Seamus tells the men to start rowing into the Irish sea. After 5 minutes Seamus shouts "Stop lads, I'll check it here", and jumps into the sea. "No good here lads it's only up to my waist, row a bit further " This they did and after 10 minutes, Seamus shouts " Stop lads I'll check here", and again jumps into the sea. " No good here lads, he says it's only up to my neck, row a bit further", which they did. After 20 minutes Seamus again shouts, "Stop lads, I'll check it here" and jumps into the sea. He plummets down and down and reaches the seabed, jumps up and down a few times and returns to the surface.

" It's perfect here lads", he says, "pass me a shovel " !!

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||