|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

Pedro’s Patter.

Excerpt from Jeff’s book – Wallaby Airlines.

A day off for Christmas, December 1966 – January 1967.

Back at home base the pace was hotting up. I wrote home in early December. Though it’s quite late (10.45 pm) I must dash off a few lines as I’m working for the next ten days straight and don’t know when I’ll next get the chance to write.

December was the busiest month of the tour so far and coincided with a gradual change in the tasking of the squadron. The new 41 mission kept an aircraft operating permanently out of Vung Tau. This aircraft was also available for Task Force air support. This fitted in with two current situations, the greater effort required to support the increased Australian Army presence in Phuoc Tuy Province and the expectation of an upsurge in VC activity in the Delta after the wet season.

In early December 1966, the new airfield at Nui Dat opened. It was named Luscombe Field. On 5 December, Luscombe was included in the daily Saigon courier. John Harris and I, with Keith Bosley as crew chief, took one of the first Wallaby flights into Luscombe two days later. And so began a more active Task Force support role for Wallaby Airlines.

Although we retained those operations that were integrated with the US airlift, we now flew more missions in direct support of the Australian Task Force, carrying men and equipment into Luscombe, or to outlying fields in Phuoc Tuy Province. Although all our operations to date had been air landing of cargo and passengers, we began practising supply and flare dropping. We spent many nights sleeping at the base on the floor of the operations room on ‘flare drop standby’, waiting to be called out to support a night operation which never eventuated (not in my time anyway). I must say, I was not very enthusiastic about this sort of work since at the height and speed required for dropping, a Caribou would be a sitting duck for sniper fire. I could not help recalling that my own father had been killed by a sniper’s bullet in World War II while flying his Hudson bomber on a supply-dropping mission in New Guinea during the Buna-Gona campaign. As expected the onset of the dry season produced a flurry of activity in the Delta, as the airlift effort focused on building up fuel supplies at MACV (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam ) outposts to be used as forward bases for helicopter gunship operations. We were heavily involved in supporting these operations. In the Delta the combination of lush jungle, tall grasses and mangrove swamps provided an ideal sanctuary for the VC, as well as plentiful food supplies from rice-growing areas. However, a high civilian population meant that indiscriminate bombing operations, such as B-52 carpet-bombing, used in the north could not be used here. Hence the reliance on small-scale search and destroy missions.

I saw a lot of Soc Trang, Cao Lanh, My Tho and Binh Thuy during November. We seemed to be aiming to cover them over with drums of POL, so often did we carry this type of cargo. One day, Mick Lewino and I were given the job of carting POL to My Tho for the whole day. To relieve the tedium of the operation, we decided to try to set some kind of record. With the cooperation and hard work of Stew Bonett and Blue Campbell, the other crew members and the support of an enthusiastic forklift driver at Charlie Ramp, we made ten return trips to My Tho, in the middle of the Delta. That day we logged 10 hours 30 minutes, at that stage the most flying time by a squadron crew during daylight hours. The forklift driver shook his head and muttered ‘Goddamn Aussies’, as we hustled him each time for a quick turnaround. But he made sure we had loading priority and was obviously proud of his part in our little scheme. Our turnarounds at My Tho took only about two minutes as we reversed to the side of the strip and rolled the drums out the back. By the time we had finished there were one hundred more POL drums beside the strip at My Tho.

A few days later Mick and I were on a different kind of task, which I wished had been unnecessary. We picked up seven corpses from Tan Son Nhut. All were the bodies of Australian soldiers killed in recent action in Phuoc Tuy Province. They had been brought from the military mortuary at Saigon to Rebel Ramp. After travelling with us they were scheduled to go home in the cargo compartment of the RAAF C-130 courier from Vung Tau instead of by airline jet as their luckier comrades would. I walked past the aluminium caskets, stacked either side of the cargo compartment on my way to the cockpit, feeling sorry for the occupants and a little unsettled about the trip. I did not even know who they were or how they had died, thousands of miles from home.

Except for a flash of interest by the newspapers, all but a few grieving friends and relatives would remember them only as statistics. Later that same day we shuttled from Xuan Loc to Dat Do, both airfields in Phuoc Tuy Province, with 70 young Vietnamese troops, reinforcements for a big Australian action going on there. I thought again of the caskets. The Vietnamese looked nervous packed like sardines into the Caribou with their weapons. Perhaps it was only fear of air travel. At Dat Do, they jogged away to unknown fates while nearby 150 mm howitzers pounded away, softening up the VC ready to do battle. How many would survive?

There was also a lot of action to the west of Saigon. There was talk of much men and equipment, which had been steadily arriving from the Ho Chi Minh Trail, being poised for a large-scale attack on Saigon. One day, Ian Baldwin and I flew four round trips shuttling ammunition from Tan Son Nhut into Moc Hoa, five miles from the Cambodian border in the so-called ‘Parrot’s Beak’ area west of Saigon. This area jutted out from Cambodia into South Vietnam, the point of the beak being only 20-odd miles from the capital. It was in an ideal position for the enemy to mass forces close to Saigon. There was some kind of airborne assault operation going on even further to the west. We counted 27 C-130s, in a large loose formation, en route.

We had to wait on the Australian newspapers to see pictures of C-130s disgorging men and equipment in a spectacular mass paradrop to realise the significance of what we had seen. Apparently, after several months of secret preparation, the US 173rd Airborne Brigade had conducted a battalion-size parachute assault north of the Parrot’s Beak. The drop zone was a wide clearing in the jungle four miles from the border near a crossroads hamlet called Katum, thought to be the site of COSVN, the Central Office for South Vietnam, the top enemy headquarters in South Vietnam. The 778-man jump was successful, with only 11 minor injuries, but the aim of the mission was not. The drop was unopposed and COSVN was not located. The 173rd returned to helicopter-borne operations.

With the dry season upon it, the Delta was now much kinder making the 406 a pleasant run. I felt on top of things. But an unwelcome incident intervened to deflate my sense of wellbeing.

Arriving at Cao Lanh one day, I noticed with some annoyance that the wind was a strong easterly. This meant a landing away from the end of the strip which widened out into the small parking area. A U-turn on the very narrow runway would therefore be required. Normally this was no problem as you could taxi off the gravel onto the dirt and make a wide radius turn. But after the recent rains, the gravel runway was an island, and venturing off it would mean certain bogging. So, I began a short radius turn. Halfway round, I felt a ‘graunch’ and the steering wheel locked. Alex Martini, the crew chief, jumped out to inspect the nose wheel and brought back some bad news. The nose wheel steering mechanism had overrun a stop, causing it to jam. I shut down the engines, and we tried to free the nose gear by pushing and pulling, all the passengers lending a hand, but to no avail. We were stuck. My jinx again? We got a message through to the squadron and made arrangements for repairs. Because we were obstructing the short 1500-foot strip, there was no hope of getting another Wallaby in. The squadron sent back a message that spare parts and a mechanic would be sent in on a Pilatus Porter, which would arrive in about three hours time.

There was no point in staying at the field, so we bundled crew and passengers inside and on the bonnet of a grossly overloaded half-ton truck belonging to the unloading team and set out for the MACV compound, five miles away. Up to this point I had never travelled more than half a mile outside urban areas. Five miles by road in the countryside can seem like 50, particularly on a minor road in the Delta. The locals along the way did not seem to me nearly as friendly as did the people at Camau. After the driver had finished telling us about recent VC ambushes and terrorist incidents, I was ready to leap into the nearest ditch if any of the innocent-looking peasants we saw suddenly brandished a firearm.

After meeting the Vietnamese province chief, an ARVN colonel, and drinking coffee with the MACV team, I was glad to get back to the airfield to supervise the repair operation. We arrived in time to see the Pilatus Porter with our tool kit on board approach over our aircraft and land in the remaining 500 feet of the strip. This aircraft, I thought, is even more remarkable than the Caribou. With the extra tools and some brute force, the mechanic and Alex soon had the nose wheel back to normal.

The 406 now included a stop at Long Xuyen, just across the Bassac River from Cao Lanh. Civilian Australian doctors and nurses from the Royal Melbourne Hospital worked at the hospital here, adding their surgical and nursing skills to the overworked and understaffed local medical team. It was a pleasant change to see a smiling Australian face waiting for the mail, and to share nostalgically the news from home. A feature in the town was a huge, half-completed Catholic Church begun during the Diem regime, like the one I had seen at Quang Ngai. We were told that, here also, when construction was abandoned many refugee families moved in and made it their home.

Another Australian we often saw at Tra Vinh these days was Tony Powell, who was doing a forward air controllers’ course at the USAF FAC School at nearby Binh Thuy. Tony survived many hazardous operational missions controlling air strikes from Cessna Bird Dogs and carrying out visual reconnaissance and other FAC duties. He also assisted No 2 Squadron to work out a system for FAC control of daylight raids by Australian Canberra bombers. For his efforts he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). Tragically, he and his wife were later killed in a car accident back in Australia.

Towards the end of the year, both our squadron and the chopper squadron seemed to be working at full throttle. I remember that I rarely had more than a day a week off, sometimes less. Most of the other pilots were working just as hard. Inevitably, tensions rose. One night, a simple disagreement in the bar led to a fistfight. In this closed male community, even personality traits could grate on people. There were other unpleasant incidents too as the pilots, tired after long working days in trying conditions, and with few outlets for their feelings, unwound in the bar. On reflection I can understand how these things happened. I remember feeling myself getting more impatient and more irritated by some of the people with whom I was continually working and living. They probably felt the same way about me. A few beers under the belt sometimes brought out normally suppressed aggression. Perhaps it was fortunate that, due to some officers moving into other accommodation there was now more room in the Villa. There were now only five instead of seven in our room. As it was a big room this gave everyone quite a bit of extra space.

Some funny things happened in this period too. One night, I woke to the sound of voices in time to see a 9 Squadron pilot climbing into bed with one of our pilots. Aha, I thought, so this is what happens when you’ve been up here for a while. But the incumbent sleeper’s vehement protestations and the other’s mumbled apologies told me it was a case of disorientation after a late night binge session in the bar. Another well-known character, this time one of my room-mates, had the disconcerting habit of sleep walking, and was liable to end up anywhere. We found him one morning sound asleep in the bottom of his wardrobe. On another occasion, he stumbled into the CO’s room. Now I happen to know the CO kept his .45 handy. Our nocturnal prowler might have been shot as a VC intruder had he not woken himself and everyone else up crashing into a metal wardrobe door.

Another story is about an unfortunate 35 Squadron pilot who suffered badly from what was colloquially called ‘the trots’ (dysentery). This pilot wore a new type of flying suit, which included a hood. One day he was taxiing along what was known as the high-speed taxiway at Tan Son Nhut, with other aircraft in front of, and behind him, all waiting to take off. This taxiway is designed to speed up the departure of aircraft that are ready to roll without delay. At this point the pilot in question suffered an urgent call of nature which he could not ignore. Closing the cockpit door he unzipped his flying suit, the new design which included a hood. Dropping it around his ankles, he resourcefully positioned an air sickness bag and did what he had to. Suddenly the tower called, ‘Wallaby Zero One, clear for immediate take-off’. Witnesses say that there was a blur of green, blue and grey as our intrepid friend whipped up his flying suit, buckled his seat belt, and slammed open the cockpit door. Unfortunately he did not realise the sick bag and its contents had lodged in the hood of his flying suit. I am told it was a pretty ‘shitty’ take-off.

There were also some unusual flying incidents. One of these occurred

when I was sent to a place called Go Cong, just across the river mouth

from Vung Tau, for the first time. The so-called airfield at Go Cong was

actually a widened section of bituminised highway. As at Camau in the

early days, ‘White Mice’ (Vietnamese policemen) were on duty and held

back pedestrians and bullock carts for our arrival. After an uneventful

landing, I attempted to turn around. The runway, more accurately

roadway, was so narrow that a forward-reverse-forward procedure was

necessary. Poking the nose of the

Approaching My Tho on another occasion with more drums of POL, I noticed that the airfield seemed strangely deserted. No one on the ground answered our radio calls. I decided to land anyway, and leave the drums beside the strip, as we had done many times before. Late in the approach, two American GIs with rifles slung over their shoulders ran out onto the runway waving their arms in a ‘do not land’ sign. We overshot rapidly. When I told Dave Marland this story, he claimed he had nightmares for weeks after, with GIs waving him off wherever he went until he ran out of fuel. As with other incidents of this kind, I never found out the explanation. My purpose in relating these various stories is to illustrate that Wallaby pilots were wise always to anticipate the unexpected and be pleasantly surprised by the normal.

For several weeks, I operated only in the Delta, carting POL to just about every MACV outpost in this part of the country. I am sure I knew every canal and rice paddy from Saigon to the south coast. Aside from listening to a fusillade of shots during lunch at An Thoi one day, as trigger-happy guards chased a suspected VC infiltrator past the Officers’ Club, nothing out of the ordinary happened. I still seemed to be jinxed. Walking out of TMC at Tan Son Nhut one day, Mick Lewino and I were just in time to see a forklift stick one of its prongs through the side of our Wallaby while taking a short cut to the next door aeroplane. Two weeks later, after a 406, Ian Baldwin and I arrived back at Saigon only to discover a massive oil leak in the starboard engine. It was too late to get another Wallaby over with a repair team in daylight, so we had to find somewhere to spend the night. We had never stayed overnight in Saigon before and had no regular contacts except TMC. I rang RAAF Headquarters only to find that everyone except the Duty Officer had gone home. The best he could do for us was a night sleeping on an office floor. Instead we accepted a lift on the back of the TMC truck and the offer of the night in borrowed beds (the owners were on R&R leave) in an incredibly scruffy room in a house in a Saigon side street. Since all we had with us was what we were wearing, namely sweaty, grimy flying suits, we were grateful for any small comforts.

Next day it was back to normal. We picked up our repaired Wallaby at Tan Son Nhut and headed back to home base. There must have been some letter writing to-and-fro prior to Christmas. One I sent home said: Concerning Christmas, I really need nothing up here—and I mean it. The only possible exception would be one or two cheap (the girls scrub things and wear them out in no time) short-sleeved shirts, either cotton or golf type, colour anything except blue. I have plenty blue. As it turned out I got my request and quite a few surprise gifts as well.

With 1966 drawing to a close, I finally cracked another Nha Trang detachment. But it was over all too soon. I arrived back to find I was programmed to fly Christmas Eve, Boxing Day and the next three days after that. But I had a day off for Christmas. On Christmas Day, we had a ceremonial opening of Christmas hampers, which had been sent to us by various kindly people and organisations. These well-meaning folk were not to know it, but between us, we had about a month’s supply of fruitcake, canned peaches, nuts and sweets. We probably introduced tooth decay into Camau, since the kids there got most of the lollies. One lot of hampers had cards in them, wishing the recipient a Happy Christmas from Fred or Bill or whoever had packed them. My card said: Wishing you a very Happy Christmas, with love from Christine. XXX. Whoever, or wherever, you are Christine, God bless you. But you cannot imagine the explaining I had to do when my wife eventually found your card at the bottom of my cabin trunk.

The catering staff excelled themselves. We feasted on roast turkey with cranberry sauce and baked vegetables, just like home, followed by plum pudding and brandy sauce. There was lots of champagne, as if there really were something to celebrate. The passage of time, perhaps? Everyone ate and drank to excess. Christmas was soon forgotten in the hassle of a New Year. It was back to flying six days a week. Those back at Vung Tau found time to accept an invitation to a New Year’s Day cocktail party at a nearby American unit. John Steinbeck, the author, was a special guest. He was doing a tour of South-East Asia and Australia, perhaps doing research for a new book. He looked very old and tired. In no time at all, I was off to Nha Trang again with Stu Spinks, glad of a change of scenery. We had now moved onto the base for security reasons. Since we no longer needed transport, we had given up our faithful Ford ‘rust bucket’.

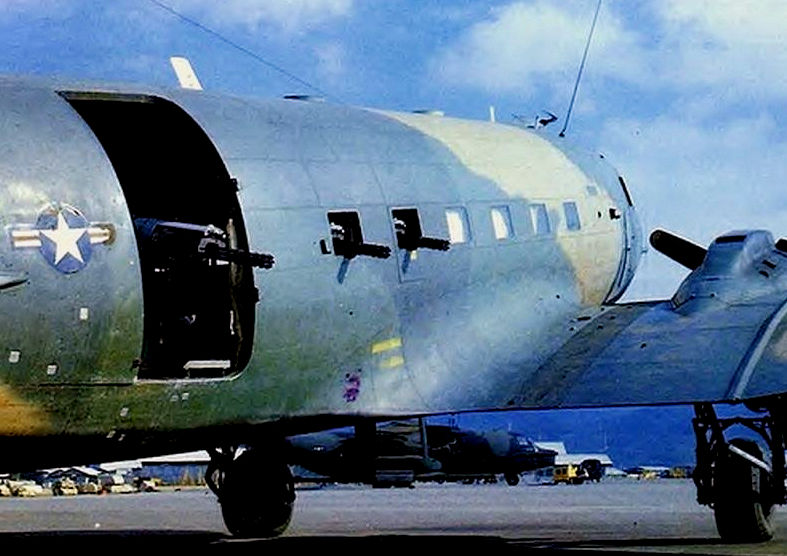

With Tet approaching, there were nightly bunker drills (which we mostly

ignored, since we needed the sleep more than the practice), and

so-called Dragonships (from ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’—DC-3s with infra-red

sensors and Gatling guns) nightly scoured the hills to the north of the

base. We watched them one night, beers in hand, the tracer from the

Gatling making it look more like some kind of Flash Gordon ray gun. When

the Gatling guns opened up at their shadowy targets, even trees in their

path were chopped to matchwood. Dragons indeed, roaming the night,

raining a hot

For the next hour and a half, he stood in the hot sun, lining up and reading the compass and recording the results. Robyn and I agreed he was one of life’s true gentlemen. We were grateful too to our friends Craig and Margaret Cousens, who put us up in their house for my four nights at Butterworth and Robyn for another week. It was strange returning to Vietnam knowing I would be flying back to Singapore in a week’s time, even stranger facing the hazards of the Delta knowing Robyn was waiting for me to return. But I finished the week in one piece, boarding the R&R special flight to join her in Singapore. We booked into the Cathay, then Singapore’s plushest hotel, and lost ourselves in each other, and the market places and nightclubs of this intriguing city. For seven whole days, we pretended that Vietnam did not exist.

Click the pic below to see an interview with Rob “Little Chuck” Connor on his experiences in Vietnam. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Humans share 50% of their DNA with Bananas.

|

||

|

Turbulence in the air.

When an aircraft hits turbulence mid-flight, some passengers will tell you the aircraft dropped thousands of feet, others will tell you it was nothing.

Who's right and who's wrong?

Recently passengers on a Qantas plane who believed it plummeted several thousand feet were assured by Qantas' chief pilot that it only ever moved its nose about three-degrees. And again, passengers on Qantas’ QF94 from Los Angeles to Melbourne believed they were about to die after the A380 aircraft encountered turbulence at about 30,000 feet above the Pacific Ocean.

“The lady sitting next to me and I screamed and held hands and just waited, but thought with absolute certainty that we were going to crash. It was terrifying,” passenger Janelle Wilson told The Australian. Ms Wilson believed the plane entered a “free fall” and was “nosediving”.

But this was a common misunderstanding of something which is “routine” in aviation, according to Qantas chief pilot Richard Tobiano. “There was no cause for concern, the plane’s nose pitch(ed) up slightly after the aircraft hit about 10 seconds of turbulence. This is routine for aircraft that encounter turbulence”, he said.

“The ‘plunge’ that a few passengers have described was actually the A380 immediately returning itself to a steady state.” The airplane climbed maybe 100 feet or so and descended back to its cruising altitude and the captain took action to avoid the further exposure to the wake vortex. The situation was handled fully in accordance with procedures and the aircraft performed as designed. Media identity Eddie McGuire who was on board the flight said the aircraft only “slightly” felt like it was “going over the top of a rollercoaster”. “There was a little bit of turning of the plane as well and a little bit of downward. It was one of those ones that got your attention. Then it levelled off.”

The aircraft was flying 1000 feet below and 37 kilometres behind another A380 Qantas plane when it was met by “some disturbed air”, Qantas’ Mr Tobiano said. Both planes were “well aware of each other” but “wake turbulence” can be difficult to predict and “often arrives as a sudden jolt when you’re otherwise flying smoothly”, Mr Tobiano said. He said the captain made an announcement during the flight to “explain what happened” because he “knew how this would have felt to passengers”.

Aside for the perceived sudden plunge, the flight was “uneventful” Mr Tobiano said. The concept of turbulence is “one of the most misunderstood elements of flying”. It can be caused by large, dense clouds and sudden changes in the wind’s direction. “Aircraft are engineered to deal with levels of turbulence well beyond anything you’d realistically encounter. “Turbulence can be unexpected and uncomfortable, but provided you have your seatbelt on whenever you’re seated, it’s not something to fear.”

|

||

|

Every year coconuts kill more people than Sharks ever do. So do Cows.

|

||

|

Amy Johnson.

Amy Johnson CBE (1903-1941) was one of the most influential and inspirational women of the twentieth century (and a damn good sort too – tb). She was the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia in 1930 and set a string of other records throughout her career.

Amy was the eldest of four sisters and grew up in Hull in the UK, where her father ran a fish export and import business. She studied at Sheffield University, before a failed love affair persuaded her to try a new life in London. She worked as a typist for a firm of solicitors until, at a loose end one Sunday afternoon, she boarded a bus that took her to Stag Lane Aerodrome in North London. She was immediately captivated by the primitive biplanes she watched taking off and landing. Soon she started to spend all her spare time at the aerodrome.

During the 1920s and 1930s aviation was dominated by the rich and famous and most female pilots were titled women such as Lady Heath, the Duchess of Bedford and Lady Bailey. But Amy gained a ground engineer’s “C” licence and, with the financial help of her father, took flying lessons. In 1929 she was awarded her pilot’s licence.

Although her flight was meticulously planned her gender remained the main point of interest for the Daily Mail, whose headline mistakenly announced, that she had set off with a, “Cupboard Full of Frocks”.

Amy left Croydon Airport for Australia on the 5th May, 1930 in a second-hand Gipsy Moth called Jason. Unlike today’s pilots, Amy had no radio link with the ground and no reliable information about the weather. Her maps were basic and, on some stretches of the route, she would be flying over uncharted land. Until her Australia trip, her longest solo flight had been from London to Hull.

Daringly, Amy had plotted the most direct route – simply by placing a ruler on the map. This took her over some of the world’s most inhospitable terrain and meant she had to fly the open-cockpit for at least eight hours at a time. It was essential that she kept to her route because fuel was waiting for her at each stop.

Despite a forced landing in a sandstorm in the Iraq desert she reached India in a record six days and the world’s press suddenly started to pay attention. She became the “British Girl Lindbergh”, “Wonderful Miss Johnson” and “The Lone Girl Flyer”.

In India she surprised an army garrison by landing on a parade ground and, when she reached Burma (modern-day Myanmar), she faced her biggest challenge: the monsoon. Outside Rangoon a bumpy landing ripped a hole in Jason’s wing and damaged its propeller. A local technical institute repaired the wing by unpicking shirts made from aeroplane fabric salvaged from the First World War.

Although the monsoon robbed her of her chance to beat Hinkler’s record, Amy landed in Australia on Saturday, 24 May to tumultuous crowds. Over the next six weeks she was treated like a superstar. Women asked their hairdressers for an “Amy Johnson wave” and the affectionate way in which she described Jason – “But the engine was wonderful” became a catchphrase.

At least ten songs were written about her, the most famous, “Amy, Wonderful Amy” performed by Jack Hylton. Fan mail poured in and such was her fame that an envelope addressed to “Amy wat flies in England” reached its destination.

She was exhausted by the physical and mental strain of her flight and found it impossible to return to normal life. In July 1931 she flew to Tokyo with her mentor and mechanic, Jack Humphreys, as co-pilot. They set record times to both Moscow and Japan.

After a short courtship, Amy married Scottish pilot Jim Mollison in 1932, and they became known as the “flying sweethearts”. Later that year Amy set a solo record from London to Cape Town and in 1933 she and her husband crossed the Atlantic – a journey made more dangerous by the need to carry large amounts of fuel and by the fact that for most of the journey they were out of reach of land. Although they crashed in Connecticut they nevertheless established another world record and America took them to their hearts. They were given a ticker tape parade in New York and entertained by President Roosevelt.

The following year the couple flew the revolutionary new de Havilland

DH.88 Comet in the Britain to Australia MacRobertson Air Race. Although

they

It was becoming harder to break records, Amy turned her attention to business ventures, journalism and fashion. She modelled clothes for Elsa Schiaparelli and created her own travelling bag, until the outbreak of the war in 1939 made her reconsider her public role.

In 1940 she joined the Air Transport Auxiliary, an organisation set up to ferry planes around the country for the Royal Air Force. On Sunday 5 January 1941 she left Blackpool in an Airspeed Oxford, which she had been ordered to deliver to RAF Kidlington, near Oxford.

At about 3.30pm a convoy of ships was approaching Knock John Buoy on Tizard Bank, off Herne Bay when a seaman spotted an aeroplane and then a parachute floating down through the snow. Several sailors then reported seeing two bodies in the water. One was described as fresh-faced and wearing a helmet. This figure called out for help in a high-pitched voice as it drifted dangerously close to the ship’s propellers.

Once it became clear that there was no hope of saving the helmeted pilot Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher, captain of the HMS Haslemere, dived into the icy water to try to save what he took to be a passenger. He was seen to reach the spot and rest beside a floating object, before attempting to return to the ship. He was rescued from the water but died later from exposure and shock at the Royal Naval Hospital at Gillingham and is buried in Woodlands Cemetery. Neither the so-called “second body”, nor Amy’s body were ever recovered. Parts of her plane and some of her possessions, including a travelling bag, a cheque book and her logbook, later washed up nearby.

Speculation about what exactly happened that afternoon and why she was so far off course has ranged from rumours that she was on a secret mission to the more mundane theory that she got lost and simply ran out of fuel. The idea of a secret mission was probably sparked by a statement issued by the Admiralty which mentioned two bodies. Although this was later corrected, other newspapers picked up the idea of “Mr X”. In 1999 a former member of the 58th (Kent) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment expressed a fear that Amy may have been shot down by “friendly fire”. This theory, however, seems unlikely, given the unit’s distance from the plane.

The mystery surrounding Amy’s final hours has only added to the mystique attached to her life. However, while the exact details of her death may never be known Amy’s bravery and pluck continue to inspire.

Click the pic below to see her arrival in Brisbane. This is a silent film, no sound.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

The probability of you drinking a glass of water that contains a molecule of water that also passed through a Dinosaur is almost 100%.

|

||

|

The Shuttleworth Collection.

If you’re interested in old aircraft – click the pic below, there are some amazing old machines here, all flying too.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

B2 Spirit bomber.

The Northrop B-2 Spirit, also known as the Stealth Bomber, is a US heavy penetration strategic bomber, featuring low observable stealth technology designed for penetrating dense anti-aircraft defences. It is a flying wing design with a crew of two and can deploy both conventional and thermonuclear weapons, such as eighty 500 lb (230 kg) class (Mk 82) JDAM Global Positioning System-guided bombs, or sixteen 2,400 lb (1,100 kg) B83 nuclear bombs. The B-2 is the only acknowledged aircraft that can carry large air-to-surface standoff weapons in a stealth configuration.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Development started under the "Advanced Technology Bomber" (ATB) project during the Carter administration; its expected performance was one of his reasons for the cancellation of the supersonic B-1A bomber. The ATB project continued during the Reagan administration, but worries about delays in its introduction led to the reinstatement of the B-1 program. Program costs rose throughout development. Designed and manufactured by Northrop, later Northrop Grumman, the cost of each aircraft averaged US$737 million (in 1997 dollars). Total procurement costs averaged $929 million per aircraft, which includes spare parts, equipment, retrofitting, and software support. The total program cost, which included development, engineering and testing, averaged $2.1 billion per aircraft in 1997.

Because of its considerable capital and operating costs, the project was controversial in the U.S. Congress. The winding-down of the Cold War in the latter portion of the 1980s dramatically reduced the need for the aircraft, which was designed with the intention of penetrating Soviet airspace and attacking high-value targets. During the late 1980s and 1990s, Congress slashed plans to purchase 132 bombers to 21. In 2008, a B-2 was destroyed in a crash shortly after takeoff, though the crew ejected safely. There are now 20 B-2s in service with the United States Air Force, which plans to operate them until 2032.

The B-2 is capable of all-altitude attack missions up to 50,000 feet (15,000 m), with a range of more than 6,000 nautical miles on internal fuel and over 10,000 nautical miles with one mid-air refuelling. It entered service in 1997 as the second aircraft designed to have advanced stealth technology after the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk attack aircraft. Though designed originally as primarily a nuclear bomber, the B-2 was first used in combat dropping conventional, non-nuclear ordnance in the Kosovo War in 1999. It later served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya.

Click the pic below to see the B2 being refuelled mid-air. Click to open it full screen - what an amazing machine. Note how the refueling door opens and closes.

|

||

|

| ||

|

|

||

|

McDonald's sells 75 Hamburgers every second of every day.

|

||

|

The Short Belfast.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Short Belfast (or Shorts Belfast) is a heavy lift turboprop freighter that was built by British manufacturer Short Brothers at Belfast. Only 10 aircraft were constructed, all of which entered service with the Royal Air Force (RAF), who operated it under the designation Short Belfast C.1.

Upon its entry into service, the Belfast held the distinction of becoming the largest aircraft that the British military had ever operated. It was also notable for being the first aircraft to be designed from the onset to be equipped with full 'blind landing' automatic landing system equipment. Following the formation of RAF Strike Command and a reorganisation of transport assets, the RAF decided to retire all of its Belfast transports by the end of 1976.

Shortly after the type had been retired by the RAF, a total of five Belfasts were sold and placed into civilian service with the cargo airline HeavyLift Cargo Airlines. These civilian aircraft were used for the charter transport of various goods, including to the RAF. One Belfast is on display at the RAF Museum Cosford. A Belfast formerly operated by Heavylift is lying abandoned at Cairns Airport in Australia and is the subject of a legal dispute for fees between the airport and the current owner of the aircraft, Flying Tigers.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The airport lodged documents in the Cairns Supreme Court calling for the Sydney-based company, which owns the white Short Belfast cargo plane, to be wound up and for it to pay more than $100,000 in outstanding rental fees.

The application shows the airport’s solicitor wrote to the owner, Flying Tiger Oversize Cargo, in early August 2016 and issued a statutory demand warning they had 21 days to pay the debt.

“A failure to respond to a statutory demand can have very serious consequences for a company,” the letter said. “It may result in the company being placed in liquidation and control of the company passing to the liquidator ...”

The Cairns Post revealed in July 2016 the plane, nicknamed “Hector” by airport workers, has been the subject of an ongoing dispute between the airport, Flying Tiger and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) and has been parked at the airport for about four years. It is “unregistered, uncertified and unairworthy”, according to CASA who said a notice had been issued to prevent it from flying until it passes testing.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Belfast at Cairns.

The huge aircraft (twice as big as a C-130) is regarded as the last of its kind in the world and aviation experts have said it would be nearly impossible to source spare parts or sell it in its current state, but the airport wants Hector gone and a letter penned by their solicitor to Flying Tiger warns they may be also seeking further compensation.

“Please note that in addition to the amount claimed in the demand, my client has suffered damages on account of the aircraft being left on its apron,” the letter said.

|

||

|

Apples, like Pears and Plums, belong to the rose family.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

aircraft almost into a clump of bamboo at the runway edge I attempted to

reverse, but with no result. A second attempt was equally unsuccessful.

‘Let me take a look’, called Dick De Friskbom, (right) the crew chief,

over the intercom. A quick check of the main wheels told him that they

were pushing the soft bitumen back behind them like a fold in a carpet.

Once he was back on board I tried a new technique. By allowing as much

room as I could and suddenly releasing the brakes with a lot of reverse

power on, I managed to jump the fold and complete the turn.

aircraft almost into a clump of bamboo at the runway edge I attempted to

reverse, but with no result. A second attempt was equally unsuccessful.

‘Let me take a look’, called Dick De Friskbom, (right) the crew chief,

over the intercom. A quick check of the main wheels told him that they

were pushing the soft bitumen back behind them like a fold in a carpet.

Once he was back on board I tried a new technique. By allowing as much

room as I could and suddenly releasing the brakes with a lot of reverse

power on, I managed to jump the fold and complete the turn.

breath of terror and destruction on their hapless victims. It was a good

time for my Rest and Recuperation (R&R) leave. I was also due for

another Butterworth trip. I elected to go to Singapore f

breath of terror and destruction on their hapless victims. It was a good

time for my Rest and Recuperation (R&R) leave. I was also due for

another Butterworth trip. I elected to go to Singapore f

achieved a record time to India they were forced to retire due to

engine trouble. Amy’s last major flight took place in May 1936 when she regained

her England to South Africa record.

achieved a record time to India they were forced to retire due to

engine trouble. Amy’s last major flight took place in May 1936 when she regained

her England to South Africa record.