|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

"Friends of the Mirage" reunion.

On the 30th June, 2018, a bunch of blokes got together at the Stockton RSL in Newcastle to celebrate and remember the aircraft they all knew so well – the French Dassault Mirage.

The Mirage entered service in December 1963. The RAAF acquired a total of 100 single seat model 111Os and 16 dual seat model 111Ds and over the twenty-four years they remained operational, 43 aircraft were lost and 14 pilots were killed. Despite these rather sombre figures, the French Lady as she was known, was very popular with her pilots, with many achieving over 2000 hours on type, and seven more than 3000 hours.

It was flown and maintained by 2 OCU, 3Sqn, 75 Sqn, 77 Sqn and 79 Sqn and saw service at Williamtown, Butterworth and at ARDU at Laverton.

The aircraft, in a clean configuration, had a sparkling performance despite a relatively modest thrust/weight ratio with an exhilarating acceleration and rate of climb in full afterburner. Very few aircraft could match its amazing roll rate. All this, coupled with the best feeling flight controls of any contemporary aircraft, made it a sheer delight to fly.

Other major users of the Mirage III were the French, Pakistan and Israeli Air Forces with a total of 1422 built.

Several RAAF fighter aircraft types established themselves as worthy of their own special niche in RAAF history. The Mirage 111O is one of those select few. Despite never being used in combat, in its long service as the RAAF’s frontline fighter the Mirage served the RAAF very well. It was pilot's aircraft and a superb example of the aerodynamicist's art. It must be remembered, however, that the Mirage was designed as a medium to high level interceptor to counter the nuclear bomber threat in the European theatre. The Matra missile was the primary weapon backed up by a 30mm gun pack. In this configuration the aircraft performed very well.

However, when Australian operations required the addition of two supersonic external fuel tanks and two Sidewinder missiles, plus the Matra, a lack of available power was apparent. As a result, the RAAF Mirage 111O was underpowered in the configuration required for our conditions. This would have been a definite handicap if offensive air interceptions had been required.

The situation was exacerbated by the fact that the aircraft could not be air re-fuelled. With the Mirage, the tanks are refuelled individually using mechanical valves. The system worked well for a short range interceptor and no thought was given to the single point refuelling needed for inflight refuelling. This significantly handicapped the aircraft's capability and radius of action as external tanks were required for all longer range operations.

Chosen to replace the F-86 Sabre, the Mirage was selected ahead of the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. Both were designed for the pure interceptor role and later adapted for limited air to ground attack work. The selection was controversial. Many considered the F-104 would have been a better choice, not least because it was an American aircraft and the RAAF had a long history of successful cooperation with the USAF in aircraft production.

It is certainly true that coping with a French design resulted in many shortcomings for the Mirage programme. Also, French influence prevented the Mirage from being employed in Vietnam and as a result two generations of RAAF fighter pilots never saw a shot fired in anger. However, in view of the appalling F-104 loss rate in Vietnam, perhaps these same fighter pilots have reason to be grateful that they had a beautiful aircraft to fly if not to fight with.

The Mirage had a top speed of 2,350 kph, a range of 4,000 km and was the first Western European combat aircraft to exceed Mach 2 in horizontal flight.

The RAAF finally retired the aircraft in 1988 and in 1990 the last 50 airworthy aircraft were exported to Pakistan

You can read the story on the Mirage HERE.

The reunion was held at the Stockton RSL and Citizens Club which is on Douglas Street at Stockton.

We don’t have a lot of photos of those that attended (we were banned) but the following were sent to us.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Peter Nelms, Don’t know, John Broughton, Don’t know.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Al Ryner, Brian Burgess, Noel Sullivan, Mick Laws.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Dave Lugg.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Wally Salzmann.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Noel Sullivan.

|

||

|

Just before they went to bed the wife said, “Did you put the bin out?”. I said I’d do it in the morning, she said, “What about the cat? I said, well I’ll ask him, but I don’t think he’ll be strong enough.

|

||

|

RAF Station Butterworth Malaya (1939-1957)

Hugh Crowther. Instrument Fitter.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) developed the airfield at Butterworth in Province Wellesley, north Malaya, on the mainland opposite the island of Penang on a “care and maintenance” basis in 1939.

RAF Butterworth was officially opened in October 1941, as a Royal Air Force station which was a part of the British defence plan for defending the Malayan Peninsula against an imminent threat of invasion by the Imperial Japanese forces during World War II. It was it ill-prepared when Japan attacked the base in December 1941.

During the Battle of Malaya, the airfield suffered some damage as a direct result of aerial bombing from Mitsubishi G3M and Mitsubishi G4M bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service based in Saigon, South Vietnam. Brewster Buffalos from the airbase rose to challenge the escorting Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters but were mauled during several of these engagements by the highly trained and experienced Japanese fighter pilots flying superior aircraft. Both RAF and RAAF aircraft were destroyed mostly on the ground and, following its rapid invasion of Malaya.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

45 Squadron RAF de Havilland Venoms at RAF Butterworth, 1957 during the Malayan Emergency.

|

||

|

The RAF airfield was subsequently captured by units of the advancing 25th Army (Imperial Japanese Army) on 20 Dec 1941 and the control of the airbase was to remain in the hands of Japanese Army until the end of hostilities in September 1945. Whereupon the RAF resumed control of the station and Japanese prisoners of war were made to repair the airfield as well as to improve the runways before resuming air operations in May 1946.

During the Malayan Emergency that was to last from 1948 to 1960, RAF as

well as RAAF and RNZAF units stationed at the airfield played an activ

Avro Vulcan at Butterworth 1965.

The station also served as a vital front-line airfield for various other units on rotation from RAF Changi, RAF Kuala Lumpur, RAF Kuantan, RAF Seletar and RAF Tengah; RAF aircraft would also use the base as a transit point to and from other RAF bases in the Far East Air Force including Singapore, North Borneo and Hong Kong connecting it between RAF stations in the Indian Ocean (Gan), Middle East and Mediterranean regions.

Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Base Butterworth was established in

1955 as part of Australia’s commitment to the Commonwealth’s Far East

Strategic Reserve, two RAAF fighter squadrons and a bomber squadron were

stationed at Butterworth throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In 1955 the

airfield was upgraded by No 2 Airfield Construction Squadron RAAF, which

took two-and-a-half years. In 1957, the RAF closed the station and

Although owned by the RAF, Butterworth was formerly placed under the RAAF’s control from July 1958.

As the Communist Emergency got underway the six Lincoln aircraft of No 1 Squadron RAAF Arrived in Malaya in July 1950, just one month after the Dakotas of No. 38 Squadron, they were the only heavy bombers in the area until 1953 when they were joined by some RAF Lincolns. The Australian Lincolns were therefore the mainstay of the Commonwealth bombing campaign, especially in the early years of the conflict when the outcome was still in doubt. From 1950 to 1958 No 1 Squadron flew 4,000 missions in Malaya. The squadron flew both pinpoint-bombing and area-bombing missions as well as night harassment raids – flying among many targets but only dropping bombs occasionally – in the manner of the RAF “siren raids” of the Second World War.

Operation Termite in July 1954 was a high point of the squadron’s service in Malaya. Five Australian Lincolns and six Lincolns from No 148 Squadron RAF took part in this operation against guerrilla camps in Northern Malaya. The Lincolns carried out a series of bombing runs and ground attacks in conjunction with paratrooper drops. The long range and heavy payload of the Lincoln made it an effective bomber, while its relatively slow speed proved advantageous in Malaya when trying to locate jungle targets. Butterworth was only a secondary landing field during these operations.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The crew of a No 1 Squadron RAAF Lincoln in front of their aircraft at Tengah in 1954.

|

||

|

The RAAF’s No 2 Airfield Construction Squadron built the main runway at Butterworth airfield as well as the control tower, fuel storage facilities, hangars, accommodation and other infrastructure. Butterworth, in northern Malaya near Penang, was leased from the British by the Australian government in order to provide a base for the RAAF component of the British Commonwealth Far East Strategic Reserve (Far East Air Force).

The Le Tourneau vehicle on the left was filled with a concrete mix from the chutes. The concrete was then taken a short distance to where the base’s main runway was being laid down. The old runway at Butterworth needed to be strengthened and extended so that the base could accommodate the RAAF’s Canberras.

Although Butterworth had been used as an airfield during the Second World War, in order to accommodate modern jet aircraft it needed substantial improvements including a new 1.9 kilometre runway, part of which had to be built over swamps and paddy fields, No 2 Airfield Construction Squadron began work at Butterworth in late 1955. The squadron’s 300 personnel were assisted by 600 Malay, Chinese and Indian labourers. Although the monsoonal environment and the waterlogged terrain meant that conditions were often trying, the airfield was completed by February 1958.

When No 2 Squadron’s Canberras arrived in July 1958, Butterworth became the RAAF’s most forward operational airbase. The Canberras of No 2 Squadron started flying missions from Butterworth immediately after arriving including formation bombing runs against Communist guerrilla targets. No 2 Squadron also had four DC3 (Dakota) aircraft which were used in the main to service the Australian Embassies in Bangkok, Phnom Penh, Vientiane and Saigon for mail, milk and supplies and to serve as a taxi for embassy staff and families; a service we called the milk run. These aircraft stayed on at Butterworth after 2 Squadron moved to Phan Rang Vietnam in 1967.

Six years later from August 1964 onwards RAAF units No 3 Squadron and No 77 Squadron also saw service with their Sabres during the Malayan Emergency flying strafing missions from Butterworth against Communist guerrilla targets. Through the Confrontation with Indonesia, these Sabre jets responded on several occasion to incursions by MiG-21 fighter jets of the Indonesian Air Force flying towards Malaysian airspace but the Indonesian aircraft always turned back before crossing the international boundary, thereby averting possible escalation.

By late 1964, Butterworth was home to the RAAF’s 78 Fighter Wing, comprising No 3 and No 77 Sabre Squadrons, an independent No 2 Canberra Squadron which also comprised a transport DC3 Dakota Flight plus No 5 UH-1 Iroquois Helicopter Squadron which also saw active service during the 1964 emergency before being transferred by RAN Aircraft Carrier HMAS Sydney to and becoming No 9 Squadron (for political reasons – it didn’t look like a direct transfer) on arrival in Vietnam. Also, during 1964 the RAAF established a Sabre presence from 78 Wing in Ubon Thailand at the invite of the Thai Government to defend against Communist insurgency following the Battle of the Plane of Jars in neighbouring Laos. This presence was later joined by a number of USAF Squadrons.

The 78 Wing support for operations in Thailand was not subject to approval of the Malaysian Government thus Ubon was referred to as Point B and Sabre aircraft transfers between Butterworth and Ubon were accompanied by Canberra cover aircraft. Ubon was manned as far as pilots and maintenance crew on three month rotation from Butterworth with major servicings also being carried out at Butterworth. Although the Emergency ended in 1960 and Confrontation in 1966, because of the tensions in South East Asia, the Australian Government kept 2 Sqn’s Canberras in Malaysia until April 1967. The Sqm was transferred to Phan Rang as part of the allied war on Communism which was not joined by the UK then under a leftist Labour Government; presumably they wanted the Soviets to win the Cold War. I remember with some anger how our guys were treated on return from Vietnam and during the Moratoriums by the then mainly 10 Quid Pommy Labor Party supporters who thought we should do the same as their UK Labour Party did. Everybody now recognises the evil empire for what it was, by any measure the Vietnam operation was a success it broke up the Russia China alliance and helped bankrupted the Soviet Union. Well done veterans!

In September 1964, during the Indonesian Confrontation, Indonesian aircraft dropped paratroopers into Johor, which increased tensions. Following riots in Singapore, a state of emergency was declared. On 3 September, 77 Squadron placed four Sabres on five-minute alert and its remaining aircraft on one-hour alert. All aircraft were armed with Sidewinder missiles and 30 mm guns and were fitted with drop tanks. On 7 September, 3 Squadron moved six aircraft to Royal Air Force Base Changi, on Singapore, and the rest of the squadron came under 77 Squadron’s command, before also going on to Singapore. An extra 15 aircraft and 52 ground crew were ferried in from Australia to help maintain the seven-day-a-week alert. By the end of the month, tensions were easing, with only two aircraft on standby, however, in November fears again escalated. When 90 Indonesians attempted to land at Malacca; both squadrons were placed on high alert. The squadron’s unit history describes 1964 as a year of “heightened unease”. Meanwhile No 2 Canberra Bomber Squadron maintained surveillance flights along the west coast including flyovers to Gan in the Maldives and back at a then safe 52,000ft to test Indonesian air defences. Another important task for 2 Squadron was testing the newly installed Bloodhound Missile installation Radar by flying toward Singapore at high speed at wave top height to see if the detection system was sensitive, these were called RadarCal flights. The Confrontation came to an end in August 1966.

During this period, No 33 Squadron RAF was stationed at Butterworth to provide ground to air defence with Bloodhound missiles. No 20 Squadron RAF with Hunter FGA9 aircraft were detached here as also were RAF Vulcans and Canberra’s. No 52 Squadron RAF provided air supply support to ground troops and police working in the Malaysian Peninsular jungle areas with their Valetta C2 twin engine aircraft along with RAF Single and Twin Pioneer aircraft. 52 Squadron also provided air support to units working in the Borneo jungle areas. The RAF also provided Air Sea Rescue helicopters (Whirlwinds) and Rescue & Range Safety Launches from RAF Glugor on Penang Island. Other RAF aircraft seen regularly included Beverly’s Britannia's, Hercules and Andover transports and RAF Victor tankers when transiting fighter aircraft such as Lightnings through to Singapore. The tempo slowed in 1967 with the withdrawal of the No 2 RAAF Squadron to Vietnam and these RAF Squadrons to the UK.

No 75 Squadron RAAF operating the Mirage IIIOs, arrived at Butterworth on 18 May 1967 with a detachment based at RAF Tengah in Singapore. The Squadron returned to Australia on 10 August 1983.

As of October 2008, the Australian Defence Force continues to maintain a presence at RMAF Butterworth as part of Australia's commitment to the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA), with No. 324 Combat Support Squadron RAAF (Used to be Base Sqn Butterworth) [HERE] and a detachment of AP-3C Orion aircraft from No 92 Wing RAAF being located at the airfield. In addition, the Australian Army maintains an infantry company (designated Rifle Company Butterworth) at Butterworth for training purposes.

On 30 June 1988, the airfield was handed over by RAAF to the Royal Malaysian Air Force and was renamed as RMAF Station Butterworth. The flying squadrons stationed there during this time were:

In January 2014 the Malaysian Government announced the site was to be sold to become a mega tourist facility.

|

||

|

I started out with nothing. I still have most of it left?

|

||

|

My Personal Experiences and Photos. Hugh Crowther No 2 Squadron 29 August 1964 to 21 January 1966.

My posting to No 2 Squadron Butterworth arrived at RAAF East Sale in March 1964, Maryrose and I were engaged so we married on 20 June and departed from Melbourne by ship the ‘Sydney’ on 14 August to arrive in Penang on 29 August 1964. The Australians serving at Butterworth in the 1960s were provided with housing rented from locals to the same standard as that provided to the British services which was far superior to that provided in Australia. On top of this all ranks were provided with an Amah and Gardener and if you were an officer a cook also.

We lived on Penang Island in the township of Tanjong Bungah. Our house was on the beach near the British Army’s Sandycroft Leave Centre, with high ceilings and terrazzo flooring, we thought we were kings! Our Chinese Amah was a bit older than us and remembered the Japs riding into Penang on bicycles at the start of the War, Japanese planes had strafed the Georgetown city centre and dropped leaflets saying any person resisting will be shot. She said there was no crime during the occupation; they had public beheadings in Penang Road George Town every week. Some of the iron lamp posts and buildings still had bullet holes in them. We used to ride past the Japanese secret police headquarters a previously grand house, but then a derelict ‘bad spirits’ building, on our Honda 55 on the way into George Town. There was a daily bus I could take to work which would take us through customs and across the strait to Butterworth by ferry, Penang was then duty free. We were all at least twice as well off there than we were in Australia and we experienced things every day that few have or will ever experience. All in all, life for any member of the RAAF serving at Butterworth in those days were the best days of their lives, I’m so glad to have lived this experience!

Butterworth was named after Lt Col Butterworth. We were privileged to have lived the very last days of the Great White Raj, everybody including the shopkeepers still addressed Europeans as Mam and Master, we can understand why the locals were not keen on Pommy Colonialism. None of the Muslim women in Malaysia then wore head coverings, but that was pre 9-11 politics.

During 1965, RAF Lightning Aircraft not then in service operated out of Singapore and Butterworth on Tropical Trials which were actually cold proofing tests as the temperature over the Equator is far colder than over the Poles (minus 75⁰C at 50,000ft). Similarly, a Vulcan Bomber with a Rolls-Royce Olympus engine fitted in the bomb bay made a number of flights out of Butterworth including some with the Olympus on full after burner in tropical trials for the coming Concord. Early in my tour there, the Vulcan, Victor and Valiant (soon withdrawn) V Bombers were still painted anti- radiation white for nuclear flash protection, later on they were painted pale blue underneath and jungle camouflage on top, The all-out nuclear war scenario was diminishing.

|

||

|

|

||

|

I dusted once, it came back I’m not falling for that again.

|

||

|

On one Canberra flight to Gan in the Maldives it was so cold in the aircraft at about 52,000ft over Indonesia the Navigator rolled up a map, stuck it over one of the cockpit heating outlets into his flying suit sleeve and another from his other sleeve and into my sleeve as I sat beside him on the jump seat so I could keep warm. The fold down jump seat was not an ejection seat so one would have to pull the door hinge pins and roll up in a ball before the pilot shoved you out with his boot prior to ejecting himself - the parachute was strapped to your backside. Thankfully this was unnecessary.

We did take a risk at this height as blood boils at 48,000ft and we did not have pressure suits. The unlined inside skin of the aircraft had a hoarfrost coating and if you touched a finger to it, it would stick. One of our guys arrived in tropical RAF Gan with frostbite on the soles of his feet. At this height you could see stars in the indigo sky at midday and the curvature of the Earth quite clearly (see right). I remember coming down to Gan and the Navigator saying it will be under that cloud, quite a small one, and as we descended through the cloud we found ourselves right on the end of the strip which went from one side of the island to the other, not bad for the old Mk4 GPI electro mechanical Ground Position Indicator driven by a once secret Green Satin Doppler radar system and gyro stabilised flux valve compass input all 1940s and 50s technology.

The backup Air Position Indicator had a cable drive coming from a fan motor in the Air Mileage Unit which balanced a diaphragm against dynamic speed pressure from the pitot head.

The old Canberra had been a top aircraft, it had been designed and built by English Electric in the UK and was built under licence both by the US and Australia, there is even a version still flying as a high altitude research plane in the US. The Canberra had two Rolls Royce Avon Engines same as the one in the Sabre with a thrust of about 7,500lbs each, it had a cartridge start so you could land and take off from any unserviced strip.

It held the World Altitude record of 70,135ft for more than 5 years and had a secret all moving tail plane elevator system for high altitude control; this was always covered when the aircraft was parked in its early days. It was the first ever aircraft with a bombsight (T4) that could toss bombs from a parabolic climb more than 20 miles from the target. But for us it was just the ultimate fun machine.

In 1965 I had flown in one of No 2 Squadrons Canberras from Butterworth to Tengah in Singapore for a big flyover for the changeover of the Chief of the Far East Airforce, we flew all the way in formation for practice and then round and round Singapore until general salute on the parade below, some of the Canberra’s were NZ and RAF (see aircraft with rocket pods in picture right) there were 20 aircraft, 8 of ours all in diamond formations some out of sight to me lying in the Bomb Aimers position. It was a very bumpy ride cutting the jet wash all the time!

The standard work practice for Instrument Fitters in 2 Squadron was duty crew one week in five, which was 24 hours every day on base on standby after hours for unscheduled aircraft movements and maintenance backlog while doing normal daytime duties as well. We got one day off for these 7 days on duty. On New Year’s Day 1965 I was doing such a duty, living in a tent next to a trench dug near the control tower, waiting for a possible attack, that day was the coldest day then recorded by the Butterworth Control Tower, 18 degrees C. It doesn’t sound cold, but we froze in our tropical uniforms! This was the height of Confrontation with Indonesia, one third of the all personnel on the Base were on duty at all times, 24 hour a day on top of rostered duties, so we did not have much time at home with our families in Penang in the first year I was there.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

We really thought we would be attacked; Sukarno was heavily armed with Soviet Bombers and Mig-21s and dropped 90 paratroopers in a foiled raid near Malacca. In the early 60s, Indonesia received more aid from the Soviet Block including China, than any other non-communist country, while Soviet military aid to Indonesia was equalled only by its aid to Cuba, Sukarno was armed and dangerous! We had an intelligence brief every Friday afternoon.

Maryrose and I lived on the beach and had rainforest right down to the water on the land next door. One night at about 1.30am we were awakened by a noise and looked out of our first floor bedroom window to see a rubber landing craft on our beach and armed Indonesian troops creeping up through the jungle. We luckily had not turned the light on and had no phone so just quietly hid until they disappeared up the hill, one peep and we surely would have been dead. At a later 2 Squadron intelligence brief, I heard there had been a foiled attack on Penang’s Water Reservoir on the hilltop not far from where we lived.

In 1972 I sat next to an Indonesian Admiral who was Chief of Naval Intelligence at an Officers’ Mess dining in night at RAAF Base Forest Hill, Wagga; he was with a delegation looking at our RAAF training methods. I told him I had been at Butterworth during the Confrontation and we instantly hit it off, he said he had joined the Navy in Indonesia before WW2 and was a Catholic, he had been to both the US and Russia for training during the 50s and early 60s. He told me of the sickening carnage in his country motivated by politics, religion and race in the days and months around the end of Sukarno’s rule. Following a failed coup on 1st October 1965 he told me the Mullahs instructed their followers to kill every Chinaman. This unfolded as a rampage, it was done mostly with bare hands, knives and clubs, whole villages and communities were eradicated innocent men women and children torn to pieces. Streets and rivers ran red with blood! Official figures for this range up to 1.5 million, he told me 6 million, but no one will ever know. The perpetrators just moved in and occupied the ravaged villages assuming ownership of the possessions of the slain. Confrontation finally formally ended in August 1966.

|

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

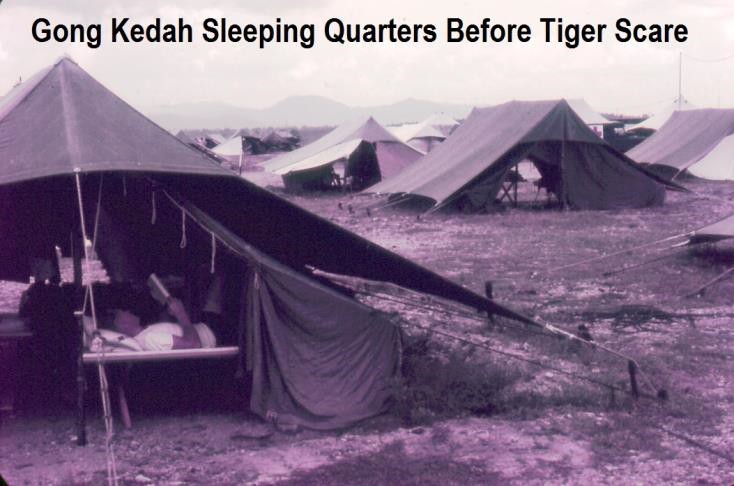

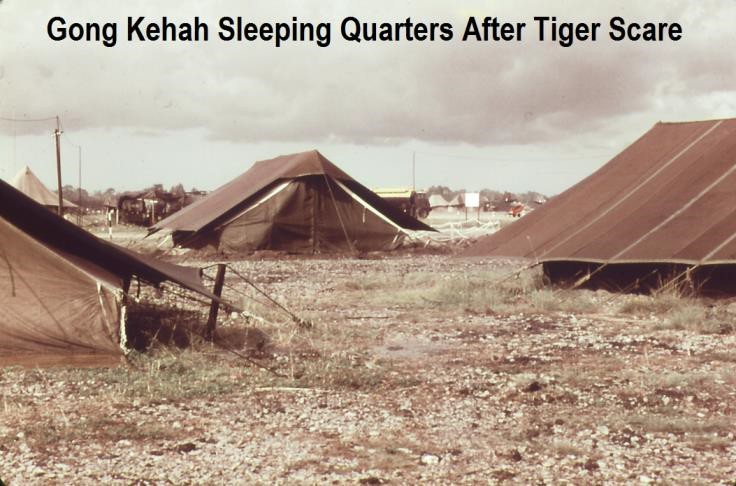

In late 1965 the Butterworth airstrip had to be resurfaced and 2 Squadron was despatched to Gong Kedah an old strip on the opposite side of Malaysia used as a forward base to attack the terrorists and still showing WW2 bomb pockmarks alongside the strip, no buildings, we lived in tents. We weren’t far from the Thai border and Chin Ping and his Communist Terrorists were still operating in this area so we had a roster of guys guarding the aircraft every night. One night we were all awoken by a rifle shot and ran over to see one of our guys standing, still shaking with his rifle in one hand and his guard dog lead in the other. Apparently, his dog started growling and snarling and the guy shone his torch around to see a tiger crouched ready to pounce on him. He had frozen with fear, luckily the tiger bounded off and he fired after it. Prior to this we had all had our tents un-staked with the flaps thrown over the top because of the heat, after this we had them staked every foot and the fly’s laced up like a boot.

On the weekends we visited the closest town Kota Baharu about 30 miles away where we had trishaw races and other mad stuff or hired local fishing boats like the boat people use to take us to nearby islands and inspected old WW2 fortifications then slipping into the sea. We took Air Force rations with us and gave the little kids oranges which they had never seen before. A local guy had a trained monkey he sent up trees to get coconuts and throw down, usually directly at us.

While we were there, the pilots were doing mostly self-set exercises having fun away from civilisation and from anyone who might know who the hell we were and report stupid behaviour to authorities.

I went flying a couple of times while there, sitting in the jump seat or lying down in the bomb aimer’s position which had a vinyl covered six foot long foam mattress. We flew along the beach so close to the ground the wheels would be underground, my face would have been less than a metre from the ground. At this height I could see a vee shaped standing wave of sand kicked up by our shockwave just below my nose through the bomb sight window. The aircraft shook so violently my helmet visor kept shaking down over my face as we rode on our own shockwave in ground effect mode, the coconut trees at the back of the beach were rushing past like a picket fence. The young pilot assured me there was no risk as he couldn’t nose in even if he wanted to as the pressure between the ground and the aircraft was keeping us clear, hence the very violent buffeting. I just loved the exhilaration of it, I never even thought of the prospect of a bird strike which could come through the Perspex nose like a 500 mile an hour cricket ball and kill me instantly. We pulled up to clear fishermen pulling in nets and bore down on Chinese junks and other boats to see if we could make the crew jump off; it was fun that would get you in gaol anywhere else.

On one occasion we flew along a raised track through rice paddies watching everybody including water buffalo hauling carts and people with bendy sticks across their shoulders with cages of chickens etc. on each end jump off into the mud and then followed a wide slow moving river through the paddy fields until we ran into forest on each side that began to tower over us at which time we pulled up to have some leaves slap our wingtip. When I examined this after getting back to base I could see the perfect leaf outline including the veins imprinted into the metal of the tip tanks which I could feel with my fingernail. I was about 22 and so were the pilots and navigators, it was a very different world then.

On the way to and from Gong Kedah we flew and took all our ground equipment in an old Beverley which looked like a piece of rubbish, we called it a Do-It-Yourself- Kit which pretty much sums it up. It had a cavernous hold with a ladder up to a passenger compartment in the tail boom with all the seats facing the back of the aircraft. There were about 30 of us and we sat in this noisy shuddering, shaking machine for about 20 minutes before we moved and one guy said he felt air sick already! Anyway, surprisingly it managed to get us there, I’ve not seen one since, perhaps even the aviation museums refuse to take them?

|

||

|

|

||

|

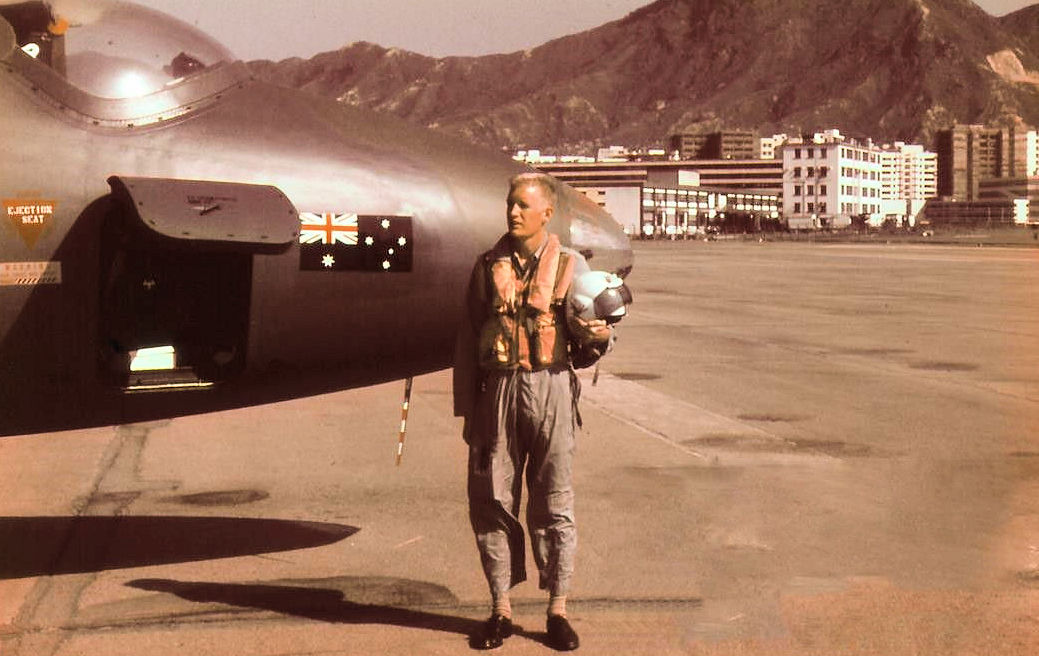

Because No 2 Squadron was part of the Far East Air Force. our Canberra’s used to fly Navigation Exercises to Hong Kong and back regularly and would always take one of the Ground Crew with them. Maryrose’s mother who was staying with us had bought a huge collection of Australian pre 1947 silver coins (which are almost pure silver) to Malaysia to hopefully sell. I took them to Hong Kong but needed the money and was diddled by the local money changer however I did manage to buy Maryrose a beautiful Mikimoto Pearl Ring quite reasonably with the spoils and was forgiven. She still treasures this ring! One other thing I did bring back was cartons of fresh milk a commodity you could not buy in Malaysia in those days.

Later in 1966, the last operational Lancaster Bomber still flying, then with the Spanish Air Force, as an anti-submarine aircraft and all painted anti-radiation white transited through Butterworth enroute to an RAF Museum in the UK.

Various US squadrons of aircraft such as F-101 Voodoos and F-102 Delta Daggers transited enroute to Vietnam from Clark Field in the Philippines, we enjoyed seeing the young pilots in their Dayglo (bright orange) flying suits and Raybans with roosters or other squadron decoration on their helmets and in some cases carrying their own personal custom chrome plated pearl handled Colt 45s in their shoulder holster. These guys looked young and confident. I remember a group standing with me getting ready to leave for Vietnam at first light in the morning watching a new Vulcan B Mk2 roar along the strip at just under Mach 1 on its arrival mission from Gan, on full after burner. It stood on its end and after a few minutes had completely disappeared directly above us in the clear blue sky, engines still roaring. One of these yanks still staring skyward exclaimed ‘Man that’s an airplane’ and it was! It was also a bit of Pommy showmanship!

As Confrontation came to an end the Vietnam War was ramping up. A trial Medivac to Vietnam was performed by No 2 Squadron using one of its four DC3 (Dakota) Aircraft from Butterworth Malaysia to Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon in early August 1996. Following this trial run it was decided an oxygen system for litter patients would be required on future missions.

2 Squadron Instrument Section was tasked with designing and manufacturing such a system. The task was given to me by the Squadron Instrument boss Flight Sergeant Alan Styling. I designed and built a Lift on Lift off Oxygen System for Litter Patients entirely from parts scrounged locally including from Canberra and Dakota in our Squadron workshops and proof tested it in less than a week, I was then a Leading Aircraftsman with nearly 8 years of service. It was completed a few days before it was needed; disposable rebreathing Masks were acquired from an RAF Squadron who shared space in our Instrument Workshop.

Following the Battle of Long Tan on 18 August 1966, 17 dead and 25 wounded soldiers were taken to the Australian Hospital at Vung Tau in the early hours of 19 August. No 2 Squadron Dakota A65-71 flew from Butterworth to Tan Son Nhut Airport Saigon on 19 August returning with 11 of the wounded on 20 August, one of these soldiers subsequently died in RAAF Butterworth Hospital on 21 August. I flew as part of this first medivac flight crew, there to operate the oxygen system I had designed and built. Subsequent Dakota Medevac Flights always included an Instrument Fitter as part of the crew to operate this oxygen system. I still have a Parker pen with a Saigon Girl in traditional clothing printed on it that was given to me by one of these grateful Diggers. On this flight the aircraft was hit by ground fire over the Mekong Delta, one of the crew said ‘I think we have been hit’ but no one else heard it, however on inspection back at Butterworth, we discovered a bullet hole through the wing just behind the fuel tank in the wing root about six inches from the fuselage forward of the cargo door.

By November 1966 Medivac flights began originating in Australia and involved the use of C130 Hercules Aircraft. The final use of the oxygen system I built was as a portable patch-in replacement for a C130 with a failed oxygen system that would otherwise have been stranded at Butterworth awaiting spares and qualified maintenance personnel from Australia. As a then Corporal, I suggested this remedy after hearing and observing the explosion of the oxygen system then being charged to 1800 pounds per square inch (psi) instead of the C130 system rated 450 psi by a local RAF out of hours servicing crew who had only experienced the RAF standard 1800 psi systems. It was about 6 am and I being on Duty Crew on the tarmac heard the explosion in the C130 parked nearby and observing thick white condensation fog exiting all open ports on the aircraft ran over to be relieved no fire or injury had resulted. If power had been on in the aircraft it would have been immolated. At this time the number of aircraft transiting Butterworth from Australia to Vietnam had ramped up considerably as our involvement in that war escalated.

Also, during this period, the first Caribou Aircraft delivered to the RAAF from Canada for service in Vietnam called in to Butterworth for Compass Swings and fitment of seat armour and other modifications. No 2 Squadron’s Dakota aircraft had already had armour plate fitted under the pilots’ seats in the Squadron workshops prior to the commencement of Vietnam Medevac’s. The Aircrew also started to take a great interest in the Canberra T4 Bomb Sight string alignments as they were being performed by the squadron Instrument Fitters in anticipation of transfer to Vietnam where the Squadron was later to receive a US Presidential Citation for their bombing record.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Butterworth had a stack of thousands of WW2 bombs, mostly 500lbs but some 750lbs, 1000lbs and others up to 2000lbs, stored in revetments that ran most of the length of the runway on the opposite side to the hangers. The 2 Squadron Armourers serviced them, sometimes carefully removing explosive fuzz growing out of them with warm water, the fuzz was very dangerous like touch powder and could set the bomb off with the flick of a finger, they were all eventually serviced and shipped via HMAS Melbourne to Vietnam for use by No2 Squadron where they were all used up in 15 months. Buccaneers like the one below were evacuated off the Aircraft Carrier Arc Royal which had a fire on board in 1966; some were in maintenance at the time and not fully serviceable hence the failure of this aircraft’s undercarriage.

|

||

|

|

||

|

No 2 Squadron Canberra’s in Vietnam 1967 - 1971

No 2 Squadron deployed from Butterworth, Malaysia to Phan Rang air base, 35 kilometres south of Cam Ranh Bay, a large USAF base in the far east of South Vietnam, on 19 April 1967. 2 SQN’s eight 'Magpies' were part of the 35th Tactical Fighter Wing and were tasked by HQ 7th Air Force in Saigon, for eight sorties per day for seven days a week, in all areas of South Vietnam from 23 April 1967 until return to Australia in 1971.

The Canberra filled a gap in the USAF inventory as it was the only tactical aircraft in South Vietnam which bombed, visually, from straight and level flight, albeit at 350knots. Often, the Canberra could fly below the cloud while the dive attack aircraft could not see the ground to acquire the target because of the low cloud base. The USN and USMC operated the Grumman A6 Intruder in all-weather attack modes, usually straight and level, using radar bombing systems. USAF F111As operated in similar modes in 1968, undergoing combat evaluation, but were withdrawn after three were lost. The F111s returned in 1972 and achieved outstanding results.

For the first few months, the Squadron carried out night Combat Skyspot missions where aircraft were guided on the bombing run by ground based precision radar. The first low level day missions started in September 1967, with forward air controllers marking the targets with smoke. Most sorties were in support of the Australian Task Force in the IV Corps area. Flying at about 3000 feet (915 metres) AGL to avoid ground fire, the crews achieved accuracies of about 45 metres. On a number of occasions, aircraft released their bombs from as low as 800 ft (245 metres), followed by a rapid pull-up to a height outside the fragmentation envelope, however, a number of aircraft were damaged by bomb fragments (shrapnel) and some navigators suffered minor injuries as a result.

HQ Seventh Air Force was impressed with the bombing accuracies of the Canberra’s when operating with FACs in close support of ground troops and by November 1967 were being tasked with four day low level sorties, however, greater accuracy was necessary to achieve the required damage levels on the targets being attacked. Bombing accuracies were improved to 20 metres CEP. (CEP = In the military science of ballistics, circular error probable (CEP) is a measure of a weapon system's precision. It is defined as the radius of a circle, cantered on the mean, whose boundary is expected to include the landing points of 50% of the rounds – see HERE.)

The Canberra achieved the transition over many years from a high level bomber with poor accuracy to a very accurate low level tactical bomber in support of ground troops. Most of the day low level operations in Vietnam were in IV Corps where the low and flat terrain resulted in the Canberra achieving very good bombing accuracy.

Flying about 5% of the Wing's sorties, 2SQN was credited with 16% of the bomb damage assessment.

Initially, bombs released were ex-WW2 war stocks. Typical aircraft loads varied from 10 x 500lb bombs to 6 x 1000 lb bombs. All the war stocks were exhausted in 15 months and 2SQN changed over to the USAF M117 bombs; 4 in the bomb bay and two on the wing tips. More reliable fuses in these bombs resulted in few of the problems experienced with the earlier British designed bombs.

2SQN aircraft serviceability was high. Eight aircraft were kept on-line and maintenance personnel worked 2 x 12 hour shifts to meet the daily tasking rate of eight sorties. The Squadron achieved a 97% serviceability rate.

North Vietnamese troops unleashed a heavy mortar, artillery and rocket attack on the Marine base at Khe Sanh on 21 January 1968, before the Tet offensive. Khe Sanh was an important strategic post and its capture would give the North Vietnamese an almost unobstructed invasion route in the northernmost provinces, from where they could outflank American positions south of the DMZ. Operation Niagara was launched to defend Khe Sanh. On the first day of the attack, nearly 600 tactical sorties (including 49 by the B 52's) were launched against enemy positions.

2SQN Canberras were involved in day and night operations, usually in pairs, and carried out visual bombing (daylight) and Skyspot missions in support of the siege. The most dangerous missions to the Khe Sanh area were flown at night when aircraft were often held in racetrack holding patterns at 20- 25 000 ft with numerous (up to 30 or 40) USAF, USN and Marine Corps aircraft.

2SQN operations continued in all Military Regions (MR), including the DMZ, the Cambodian/Laos border, the A Shau Valley and Khe Sanh from 1969 to 1970. In all operations, the Canberras achieved excellent bombing results.

On 3 November 1970, the first Canberra (A84-231) was lost during a Skyspot mission in the Danang area. The aircraft was not found until February 2009 - see the article on Magpie 91 HERE.

Another aircraft, A84-228, was lost in March 1971 in the Khe Sanh area. The crew, WGDCR John Downing and FLTLT Al Pinches, ejected and following their rescue the next day by a 'dustoff' UH-1H rescue chopper, confirmed they had been hit by a SA-2 missile, which blew the right wing off.

The last Canberra mission in Vietnam was 31 May 1971 and was tasked in support of the US 101st Airborne Division in the A Shau Valley, an area frequented by the squadron many times over the previous two years. 2SQN released a total of 76,389 bombs in its time in Vietnam.

The squadron departed Phan Rang on 4 June 1971, arriving back in Amberley on 5 June, 13 years since it deployed to Malaya in 1958. 2 Squadron air and ground crews performed exceptionally well in the air war in South Vietnam and carried on the fine traditions of strike squadrons in the RAAF.

(This Article by Lance Halvorson (right) Navigator 2SQN November 1964 - November 1967)

2 Squadron the Most Highly Decorated Squadron in the Royal Australian Air Force.

No 2 Squadron formed at Kantara, Egypt, in September 1916 and after training in England began combat operations over the Western Front in October 1917. Flying at very low levels, the Australian pilots wreaked havoc on the German troops, however, exposed to heavy ground fire, squadron casualties were high.

Lieutenant Huxley claimed No 2 Squadron's - and indeed the Australian Flying Corp's - first aerial victory on 22 November, when he shot down an Albatross scout during a ground strafing mission. From 1917 until the end of the war, No 2 Squadron worked in close co-operation with No 4 Squadron and continued to inflict heavy losses on the Germans.

When Word War II was declared in 1939, No 2 Squadron Avro Ansons were conducting coastal patrols and providing convoy escort to the ships carrying Australian troops to the Middle East. After deploying to the Dutch East Indies in 1941, reconnaissance and bombing operations were mounted against the advancing Japanese forces. In the face of attacks on its bases and heavy losses to enemy fighters, No 2 Squadron maintained its offensive efforts for the remainder of the war, providing vital information on Japanese shipping movements.

In recognition of No 2 Squadron's heroic stand in this, Australia's darkest hour, the unit was later awarded a United States Presidential Unit Citation - the highest honour that can be bestowed on a combat unit by the United States government.

In 1958, No 2 Squadron moved to Butterworth on Malaya's east coast, providing vital security during the 1960's when tensions with Indonesia and the newly-independent Malaysia resulted in a period of "Confrontation" between Commonwealth and Indonesian forces.

April 1967 saw No 2 Squadron commence operations against Communist forces in Vietnam. Missions were flown both day and night and No 2 Squadron quickly established itself as the most effective bomber squadron in Vietnam. On its return to Australia in 1971, having flown nearly 12,000 operational sorties for the loss of only two aircraft, No 2 Squadron was awarded the Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry and a United States Air Force Outstanding Unit Commendation.

These two awards, combined with the Presidential Unit Citation awarded previously, give No 2 Squadron the distinction as the most highly decorated unit in the Air Force. After flying its last operational flight in July 1982, the squadron was disbanded. The squadron reformed at RA Base Williamtown in January 2000 and will be the Air Force's designated Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) Squadron under the command of the Surveillance and Response Group. In May 2010 No 2 Squadron once again returned to the skies in the Boeing Wedgetail AEW&C aircraft. Initial efforts for the squadron have concentrated on conducting conversion courses for aircrew and maintenance personnel, and in July 2011, marked an important milestone with participation in Exercise Talisman Sabre alongside US Forces and other ADF assets

Dispelling Leftist Crap - (Like this below)

“It really bothers me that a coward like George W. Bush spent the Vietnam War training to fly old and useless planes in Texas while John Kerry was heroically risking his life in combat and got three purple hearts!” - Jennifer Braun

We normally shy away from the world of politics, but we get variations of this kind of question regularly and feel it necessary to clarify some information. We'll do our best to avoid bringing our own political biases into this article since we are more interested in defending an "old and useless" aircraft than any particular politician!

George W. Bush's military service began in 1968 when he enlisted in the Texas Air National Guard after graduating with a bachelor's degree in history from Yale University. The aircraft that he was ultimately trained to fly was the F-102 Delta Dagger. A number of sources have claimed that Bush sought service in the National Guard to avoid being sent to Vietnam, and that the F-102 was a safe choice because it was an obsolete aircraft that would never see any real combat. However, those perceptions turn out to be incorrect, as will be seen shortly.

The F-102 was a supersonic second generation fighter designed in the early 1950s for the US Air Force. The primary mission of the aircraft was to intercept columns of Soviet nuclear bombers attempting to reach targets in the US and destroy them with air-to-air missiles. The technologies incorporated into the aircraft were state-of- the-art for the day. The F-102 set many firsts, including the first all-weather delta-winged combat aircraft, the first fighter capable of maintaining supersonic speed in level flight and the first interceptor to have an armament entirely of missiles. Among the many innovations incorporated into the design were the use of the area rule to reduce aerodynamic drag and an advanced electronic fire control system capable of guiding the aircraft to a target and automatically launching its missiles.

The F-102 made its first flight in 1953 and entered service with the Air Defence Command (ADC) in 1956. About 1,000 Delta Daggers were built and although eventually superseded by the related F-106 Delta Dart (belw), the F-102 remained one of the most important aircraft in the ADC through the mid-1960s. At its peak, the aircraft made up over half of the interceptors operated by the ADC and equipped 32 squadrons across the continental US. Additional squadrons were based in western Europe, the Pacific, and Alaska.

|

||

|

|

||

|

As the 1960s continued, many of these aircraft were transferred from the US Air Force to Air National Guard (ANG) units. By 1966, nearly 350 F-102s were being operated by ANG squadrons. A total of 23 ANG units across the US ultimately received the fighter, including squadrons in Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

One of the primary ANG units to receive the F-102 was the 111th Fighter Interceptor Squadron (FIS) at Ellington Air National Guard Station, which operated the aircraft from 1965 through 1974. These planes were given responsibility for patrolling the Gulf Coast and intercepting Soviet Tu-95 bombers that regularly flew off the US shore while carrying a payload of nuclear weapons. The 111th was and still is part of the 147th Fighter Wing in Houston, Texas. It was here that George W. Bush was stationed following his enlistment in May 1968.

It is a common misconception that the Air National Guard was a safe place for military duty during the Vietnam War. In actuality, pilots from the 147th Fighter Interceptor Group, as it was called at the time, were conducting combat missions in Vietnam at the very time Bush enlisted. In fact, F-102 squadrons had been stationed in South Vietnam since March 1962. It was during this time that the Kennedy administration began building up a large US military presence in the nation as a deterrent against North Vietnamese invasion.

F-102 squadrons continued to be stationed in South Vietnam and Thailand throughout most of the Vietnam War. The planes were typically used for fighter defence patrols and as escorts for B-52 bomber raids. While the F-102 had few opportunities to engage in its primary role of fighter combat, the aircraft was used in the close air support role starting in 1965. Armed with rocket pods, Delta Daggers would make attacks on Viet Cong encampments in an attempt to harass enemy soldiers. Some missions were even conducted using the aircraft's heat-seeking air-to-air missiles to lock onto enemy campfires at night. Though these missions were never considered to be serious attacks on enemy activity, F-102 pilots did often report secondary explosions coming from their targets.

These missions were also dangerous, given the risks inherent to low-level attacks against armed ground troops. A total of 14 or 15 F-102 fighters were lost in Vietnam. Three were shot down by anti-aircraft or small arms fire, one is believed to have been lost in air-to-air combat with a MiG-21, four were destroyed on the ground during Viet Cong attacks and the remainder succumbed to training accidents.

Even in peacetime conditions, F-102 pilots risked their lives on every flight. Only highly-qualified pilot candidates were accepted for Delta Dagger training because it was such a challenging aircraft to fly and left little room for mistakes. According to the Air Force Safety Centre, the lifetime Class A accident rate for the F-102 was 13.69 mishaps per 100,000 flight hours, much higher than the average for today's combat aircraft. For example, the F-16 has an accident rate of 4.14, the F-15 is at 2.47, the F-117 at 4.07, the S-3 at 2.6, and the F-18 at 4.9. Even the Marine Corps' AV-8B Harrier, regarded as the most dangerous aircraft in US service today, has a lifetime accident rate of only 11.44 mishaps per 100,000 flight hours.

The F-102 claimed the lives of many pilots, including a number stationed at Ellington during Bush's tenure. Of the 875 F-102A production models that entered service, 259 were lost in accidents that killed 70 Air Force and ANG pilots.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

e

role in helping to curb the communist insurgency in the jungles of

Malaya by attacking suspected hideouts and harassing the communist

guerrillas. After the war, in 1950, the RAF established Butterworth as

part of their Far East Air Force bases, and squadrons based there were

heavily involved in attacking communist targets during the twelve year

Malayan Emergency.

e

role in helping to curb the communist insurgency in the jungles of

Malaya by attacking suspected hideouts and harassing the communist

guerrillas. After the war, in 1950, the RAF established Butterworth as

part of their Far East Air Force bases, and squadrons based there were

heavily involved in attacking communist targets during the twelve year

Malayan Emergency. transferred the airfield to the Royal Australian Air Force and it was

promptly renamed as RAAF Base Butterworth, becoming the home to numerous

Australian fighter and bomber squadrons stationed in Malaya during the

Cold War era.

transferred the airfield to the Royal Australian Air Force and it was

promptly renamed as RAAF Base Butterworth, becoming the home to numerous

Australian fighter and bomber squadrons stationed in Malaya during the

Cold War era.