|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||||||||||||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||||||||||||

| Fort Queenscliff

A lot of these pics have been crunched to allow the page to open faster - you can obtain the HD version of each pic by clicking that pic.

|

||||||||||||

|

Fort Queenscliff is located about 110 kms from Melbourne, on the western entrance to and just inside Port Phillip Bay on the Bellarine Peninsula. The site was known as Shortland’s Bluff. It occupies an area of 6.7ha on high ground and overlooks the shipping lanes leading to Melbourne and Geelong and has been occupied by military forces since 1860. It is now the permanent home of the National Archives. Public entrance to the Fort is via the gate on the right.

Click HERE to read the sign at entrance.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

The Fort is a superb example of the defences that existed around the coastline of Australia from colonial times through to the end of the Second World War. Considerable restoration has been accomplished in recent years, including the recovery and refurbishment of some of the original guns, the restoration of historic buildings and the development of a comprehensive indoor display and archival centre. Fort Queenscliff has been classified by the National Trust and entered in the Register of National Estate.

|

||||||||||||

|

A museum was established in 1982 to show the significance of the Fort in the local, state and national context and to provide a centre for historical research.

|

||||||||||||

|

The First Settlement

In 1852, the Lieutenant Governor of Victoria commissioned a surveyor to lay out a town at Shortland’s Bluff. On 1 May 1853, he appointed a postmaster at the Bluff to tranship Geelong and Western District mails. This first settlement was proclaimed Queenscliff on 23 June 1853 and two months later the first town lots were sold. Prior to these developments, between 1838 and 1843, pilot operations had begun shepherding ships through the notorious “rip”, a grazing lease had been granted and a lighthouse had been established in the area. In 1853-54, cottages for the pilots and a house for the Health Officer at the Quarantine Station were built and a Customs Officer was appointed.

A church and school, the first hotel and a second lighthouse were also built. The telegraph office was built and began operations in January 1855. The pilots’ cottages were mainly occupied by the Health Officer and Customs boat-crews because the pilots preferred to live elsewhere, they commissioned some of the first private dwellings in the town. In the next few years, development continued and more houses, shops and hotels were built and by the time the Borough was incorporated in 1863, Hesse Street was established as the main street of the town. Queenscliff then boasted five hotels, a library and cricket and recreation reserves. In addition, there was a lifeboat, a jetty and small steamers began offering trips around the Bay.

The Presbyterian church had been opened, a Church of England was being created and a site had been selected for the Roman Catholic church (right). A fishing industry had commenced in the town and the first requests had been made for a railway.

A detachment of the Victorian Volunteer Artillery and Rifle Corps had been formed in Queenscliff in 1859 and in 1961 construction of a gun battery began at Shortland’s Bluff which caused the building of two new lighthouses. The original lighthouse stood on the site now needed for the battery.

The Town Grows

A railway line from Geelong opened in 1879 which allowed better public access to the Bellarine Peninsula area and improved the supply of building materials to the Queenscliff area. The fortifications at Shortland’s Bluff were extended and, in 1885, the Victorian Permanent Artillery moved to Queenscliff.

Queenscliff became one of the most popular Victorian seaside resorts until greater prosperity and the increasing popularity of the motor car enabled people to look further afield for their holidays. The attraction of the town for the holiday-maker came from its unique blend of military and civilian activities, the picturesque fishing fleet and the ever-changing seascape.

|

||||||||||||

|

Say what you will about women, but I think being able to turn one sentence into a six-hour argument takes talent.

|

||||||||||||

|

Public Concern

The defences at Queenscliff and elsewhere around Port Phillip Bay were developed in the second half of the nineteenth century to protect Melbourne and its outlying settlements from invasion by hostile foreign powers. These hostile powers were, at various times, identifies as the French, the Russians, and at one stage during the American Civil war, as the United States.

In particular, the Crimean War (1853-56) stimulated public concern over Victoria’s defences and after protracted discussions, reports and inquiries, Captain (later General Sir) Peter Scratchley (right) of the British Army arrived in Victoria to advise on the development of the Colony’s coastal defences. His recommendations included a proposal to construct four large batteries of guns at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay, and suggested Shortland’s Bluff as the site for one of these batteries. He also recommended the construction of an inner ring of gun batteries at Hobsons Bay (near Port Melbourne) to provide a more intimate protection for Melbourne. He also designed the Fort to protect Newcastle in NSW.

Other than the completion of the Shortland’s Bluff battery, little work was actively undertaken on Scratchley’s recommendations for the next fifteen years. In 1875, a colonial Royal Commission recommended that the Director of Works and Fortifications in London, Lieutenant General Sir William Jervois be invited to Victoria to further advise on Victoria’s defences. He arrived in 1877 accompanied by the now Colonel Peter Scratchley. Their joint report again recommended that the basic defences for the Colony should be concentrated on the Heads and consist of fortifications at the entrance to the Bay and on the shoals between the main shipping channels. Between 1879 and 1886 their recommendations were substantially actioned and these Bay defences were progressively developed.

|

||||||||||||

|

The Bay Forts

Fort Queenscliff was developed as an enclosed battery armed with heavy calibre cannons. Swan Island at the northern end of town covered the western shipping channel and was similarly fortified. Two ‘island’ forts at Popes Eye and South Channel, were to be raised on existing shoals in the Bay to cover West, Symonds and South Channels. Although the South Channel Fort was eventually built, work on Popes Eye Shoal was discontinued because of cost and the development of torpedoes that could effectively block Symonds Channel. These torpedoes and mines were located at Swan Island and were to be laid across the shipping channels in times of tension.

The fortifications at Point Nepean and Point Franklin on the eastern side of the Bay were also developed and, although on a lesser scale, were similar to those at Fort Queenscliff. By design, Fort Queenscliff became the command centre for the Heads defences, probably because of its strategic location and established telegraph links with Melbourne. In recognition of its importance, a Iandward defensive system around the Queenscliff guns was commenced in 1882 and by 1886 Port Phillip was the most heavily fortified port in the southern hemisphere. Over the next 50 years, the Bay Forts were manned and both Fort Nepean (on the eastern side of the Bay) and Fort Queenscliff were fully operational during both world wars.

In 1946 Fort Queenscliff ceased to be a coastal artillery station and since then has housed the Australian Army’s Command and Staff College (until 2001) and now the National Archives.

The other Bay forts have since fallen into disrepair.

|

||||||||||||

|

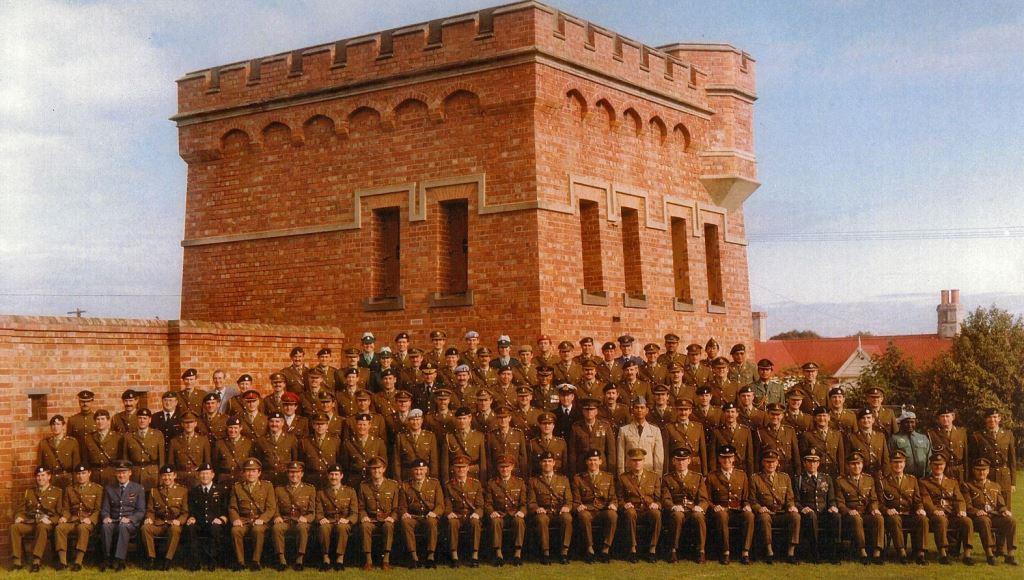

Army Staff College

Back in July 1938, the Army established the Command and Staff School in Sydney. Twenty-nine Major Generals, Brigadiers, and Colonels attended the first course of one-week duration. In October 1940 the Command and Staff School moved to Duntroon in the ACT where courses were lengthened to 12 weeks duration.

|

||||||||||||

|

On the 15 April 1942 the School was renamed as the Staff School (Australia). It was amalgamated with the Royal Military College under the one command and in August 1942 the School was divided into two wings: the Senior Wing for Grade 1 appointments; and the Junior Wing for Grade 2 appointments.

At the end of World War II, the Federal Government decided to increase the strength of the post-war Regular Army and Cabinet gave approval for the establishment of a Staff College and in February 1946, the Staff School was re-named the Australian Staff College. Authority was given to raise the College and to locate it at Fort Queenscliff. Because the Fort was not ready for immediate occupation, in June 1946, a temporary home was found for the College at the School of Infantry, in Seymour Victoria. On 26 October 1946, the advance party of the College arrived at Fort Queenscliff and the first staff course to be conducted at the new College began in January 1947.

An officer from the Indian Army attended No 10 Course of the Staff School. Other overseas representation at the Australian Staff College began in 1948 when two officers from the United Kingdom and one from Canada attended. Since then, students from many different countries have attended. At least one student from the RAAF and one from the Australian Public Service have attended almost all Courses since 1952. A total of 1788 students had graduated from the Australian Staff College at Fort Queenscliff by December 1981.

Only in November 1979, after much thought and discussion, was it decided that the Australian Army Staff College would have a permanent home at Fort Queenscliff.

|

||||||||||||

|

On 1 January 1982, the College was renamed the Command and Staff College. This reflected the new aim of the Course which included both command and staff aspects. New support facilities were opened at Crow’s Nest Barracks in 1985 and work began in 1986 on the new instruction block at Fort Queenscliff.

On 29 January 1988, the new Military Instructional Facility (MIF) was officially opened by the then Chief of the General Staff (CGS). The MIF features a lecture hall, a model room, syndicate rooms, computer centre, and library. Major rebuilding of the Officers Mess and Mess Accommodation was completed in mid-1990. By December 1996, 1224 officers had graduated from the Command and Staff College.

The last course conducted under single service auspices, graduated in December 2000, thus bringing to a close a successful 62 years of Command and Staff College operation.

|

||||||||||||

|

Every refrigerator has a crisper drawer which is a great place to hide your veggies while they rot. |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

The 1880’s

The first military works at Queenscliff commenced in 1860, with the construction of a sea wall along the top of Shortland’s Bluff. Built from sandstone quarried at Point King, this sea wall was positioned directly east of the site of the original upper lighthouse. It was designed to strengthen the cliff face and allow the positioning of heavy calibre guns in an elevated location, right on the edge of the Bluff. Also during 1860, the Queenscliff Company of Volunteer Artillery (of 50 men) received its first official commander, Acting Lieutenant Alexander Robertson.

Between 1861 and 1864, the construction of the first permanent battery, directly above the sea wall, was completed from local sandstone at a cost of £1,425 ($2,850)

Designed in a quarterfoil pattern, it accommodated four 68 pound muzzle loading cannons which were manned by the Volunteer Artillery, made up of local residents. The building of this battery required the construction of new lighthouses. In 1861, contracts were let for the lighthouses to replace the timber framed leading light built in 1854 and the badly decaying sandstone upper light. Both new lighthouses were built in dressed basalt and by February 1863 were operational. (The timber light was subsequently re- erected at Point Lonsdale.)

|

||||||||||||

|

Friendship is when people know all about you But like you anyway.

|

||||||||||||

|

In 1862-63, lighthouse keepers’ quarters were erected at the Bluff for both Queenscliff lighthouses. The upper quarters still survive within the Fort. Between 1864 and 1879, the rate of military construction at Queenscliff declined. In 1870, as the last detachment of British troops left Victoria, the debate on the Colony’s defences remained unresolved and the future of the Queenscliff battery was by no means certain.

|

||||||||||||

|

The “black’ lighthouse at Queenscliff is the only one in the southern hemisphere and one of only three black lighthouses in the world. |

||||||||||||

|

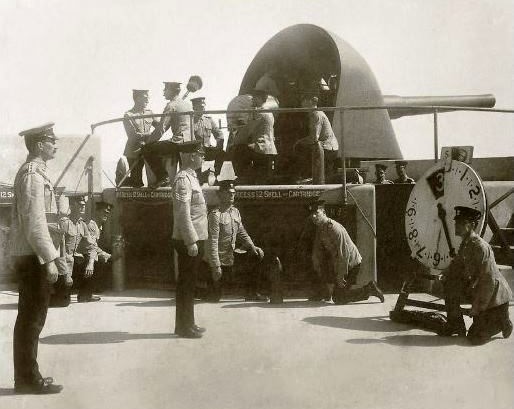

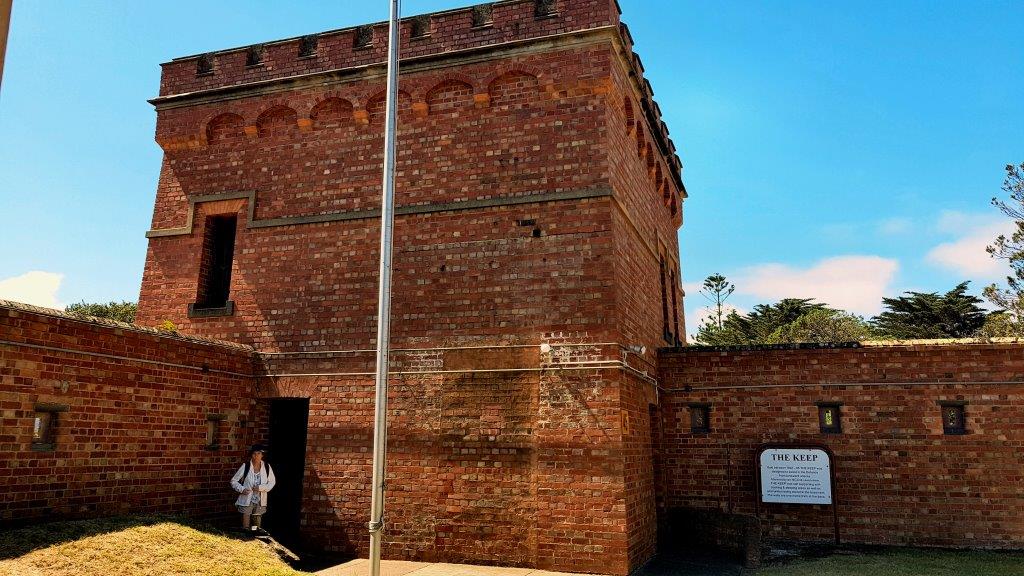

Major Development

The period 1879-1889 was the major stage of development at Fort Queenscliff. New works recommended by Scratchley and Jervois were started and formed the basis of the layout of the Fort as it stands today. In 1879, two contracts were let for the construction of an upper and a lower battery. The lower battery was to contain four 80 pounder rifled muzzle loading (RML) guns and the upper battery, three 9inch RML guns. Both batteries were completed by early 1882, although not armed. In 1882, work commenced on the walls of the Fort and a Keep and proceeded erratically until their completion in 1886.

Click HERE to read the sign.

|

||||||||||||

|

A year later a ditch or dry moat was excavated around the Fort walls to provide a further defensive measure. An array of support facilities were also erected, including a drill hall (1882), barracks (1885) assorted sheds and stores, a guard house (1883) and a separate cell block (1887).

|

||||||||||||

|

These buildings were all constructed from timber and corrugated iron, were purely functional and had little architectural embellishment. Many of them still exist today. With the erection of the wall, the civilian presence in the Fort came to a virtual end and, by 1887, both the lighthouse keepers’ quarters and the post and telegraph office were turned over to military use. From then, regular civilian entry to the Fort has been restricted.

After 1890, apart from continual improvements to the Fort’s guns and their emplacements and the construction of search-light apertures, little development took place within the Fort until the 1914-18 War. Around 1915, substantial development occurred along the northern boundary of the parade ground which involved the removal of an old shrapnel mound from behind the wall and the erection of a number of timber barracks and mess buildings.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

All the old barrack buildings were demolished in 1936 to allow the construction of the present red brick buildings (below). In recent years, portable classrooms have appeared within the Fort and a number of old sheds and stores have been demolished. One of the more unfortunate aspects of development since the 1930’s has been the encroachment of structures outside the Fort Walls, especially on the Hesse and King Street sides. In terms of layout and despite some changes in architectural style, the Fort, as it stands today, is almost the same as it was in 1889.

|

||||||||||||

|

Though over two hundred military units have been associated with Fort Queenscliff since the 1860’s two major groups of permanent soldiers have been based here: the coastal gunners of the artillery and their technical support provided by the sappers of the fortress engineers. As well, there were Militia (part-time) soldiers who were to bring the Bay forts to full strength during wartime and who trained at the Fort throughout the year.

|

||||||||||||

|

The routine of the Fort governed the lives of its occupants. New recruits were given rigorous training by experienced non-commissioned officers, but given few privileges until they had fully joined their regiment. Married recruits were normally not accepted — indeed soldiers had to notify their Commanding Officer and, at times, gain his approval to marry. Prior to World War One, the married establishment, that is those who were entitled to married quarters and rations, was severely restricted. Food was very basic and monotonous. One incident in the early 1900’s told how for weeks on end there was no ‘pudding’ until constant demands resulted in a desert made from boiled cabbage scrapsl

Sobriety was encouraged, not always successfully, by the establishment of a soft drink bottling factory inside the Fort.

A conservation study initiated in 1982 by the Department of Defence analysed the Fort and its cultural significance. After assessing archaeological, architectural, historical and environmental factors, the study concluded: ‘The significance of Fort Queenscliff and its location on Shortland’s Bluff can be viewed at a number of levels:

Historically:

Militarily:

Although a number of other examples of their works remain, Queenscliff is one of the largest, both in terms of area covered and ordnance mounted. As the central command post for the defences of the Bay, it was the premier Fort.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

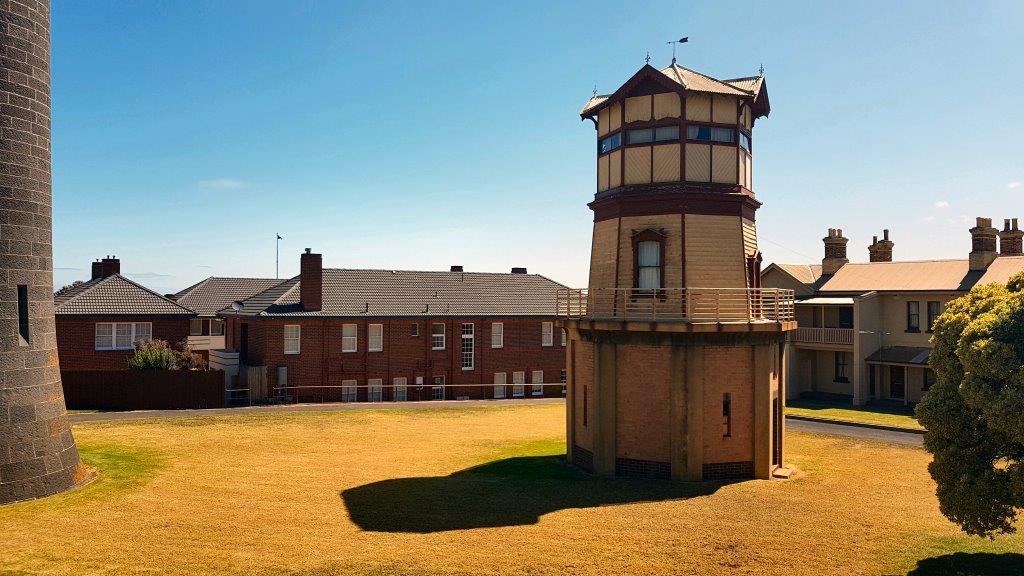

The Signal Station

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

The signal Station was built in 1888 near the site of an earlier structure, It was used to signal to and from the shipping entering “The Heads” (the Rip). In 1951, the radio control room at the Port Lonsdale lighthouse (at the mouth of Heads) assumed this function.

In 1935 the original two story octagonal timber structure was jacked up and the brick lower story built underneath. This was so the station could see the entrance to Port Phillip over the roof of the adjacent (red brick) artillery barracks which were built the following years.

|

||||||||||||

|

Common sense is like deodorant The people who need it most don't use it. |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

The old Guard House.

|

||||||||||||

|

The Fort’s significance relates to the fact that the site on which it is built has been utilised for military purposes for over one hundred and twenty years. Although not utilised in the manner in which it was originally designed, this continued occupation has been instrumental in maintaining the Fort as an example of living history as opposed to being a museum piece. Today the Australian Army is very much aware of its responsibilities preserving the Fort as part of Victoria’s heritage.

|

||||||||||||

|

Preserving the Heritage

The Fort Queenscliff Museum was formed in 1982 for the purpose of raising and maintaining a display and archival centre, obtaining, refurbishing and reinstalling original guns and equipment re-establishing and restoring the original fortifications and facilities and last but no means least, raising funds. This Museum is authorised by the Department of Defence and recognised by the Victorian Ministry for the Arts, the Museums Association of Australia and the National Trust.

To date several guns have been recovered, refurbished and re-established at Fort Queenscliff, including the recovery from South Channel Island of a 65 tonne on a hydro-pneumatic or ‘disappearing’ mounting. (Click HERE to see a demonstration on how it was fired). Considerable work has also taken place on the restoration of most of the defensive positions and some of the underground magazines. A significant archival collection has also been established. In recognition of these efforts, in 1983, the Fort was awarded the Museum of the Year’ award for Victoria. Today the Fort Queenscliff Museum receives support from a wide range of government and private organisations and many interested individuals.

Since 1983, approximately 35,000 people have visited the Fort annually. Many of these are school children visiting on excursions. It is expected that the ongoing restoration program will result in a substantial increase in the number of visitors and an increase in public interest. The ultimate objective of the Fort Queenscliff Museum is a fully restored Fort and the development of a ‘Grande’ museum which will allow visitors to tour the Fort and inspect a multitude of indoor and outdoor displays.

|

||||||||||||

|

Defence Archives

|

||||||||||||

|

The Defence Archives and the Soldier Career Management Agency moved to Fort Queenscliff and now occupy several of the newer red brick buildings.

Today visitors are encouraged to look upon Fort Queenscliff as a part of the national heritage which belongs to all Australians, accordingly, the Fort Queenscliff Museum has sought to create an environment that evokes public interest and reminds visitors of our early military history.

If you’re down that way, put the Fort on your bucket list – it is definitely worth a visit. The tours take between 1½ to 2 hours, the staff are very friendly, very knowledgeable and go out of their way to explain everything. There is a fair bit of walking but at a pace where most people can keep up. Make sure you take a hat as you're out in the open during the tour and there is no restriction on photography. Photo ID for all adults is required.

Entry Costs are:

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

You can pay via Visa, Mastercard, Amex and even cash too, if you've got any. Entry gates to Fort Queenscliff are located in King Street, Queenscliff. Gates open 10 minutes before the tours start. |

||||||||||||

|

Telephone: (03) 5258 1488 or email: museum@fortqueenscliff.com.au

If you are lucky enough to be on a later afternoon tour, you might see the Spirit of Tasmania passing through the heads.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Every woman’s dream…….Her ideal man takes her in his arms, throws her on the bed and cleans the whole house while she sleeps.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|