|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

Contents

Windscreen replacement - 34 Sqn

|

||

|

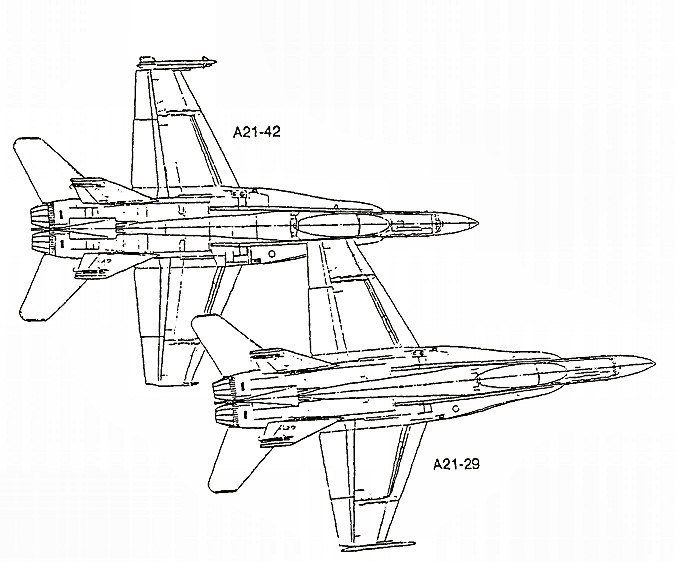

F/A-18 mid-air collision, Tindall, 02 Aug 1990.

Two F/A-18 aircraft from 75 Squadron (A21-29 and A21-42) were practising a simulated pairs intercept. In this exercise, two aircraft track an electronically generated radar return presented on their head-up displays. The aircraft manoeuvre until one achieves parameters which satisfy missile launch requirements. Missile launch is simulated and the launching aircraft continues to provide radar illumination of the simulated target throughout the computed missile flight time. |

||

|

|

||

|

Aircraft manoeuvres are quite violent throughout the interception and a

high degree of teamwork is required. Head-up displays are recorded on

videotape during the exercise. An inspection of the tape from A21-29

showed that the aircraft was pulling about 3.3g in a 90' banked turn to

starboard, Mach 0.86, altitude 32,000 ft, when it collided with A21-42.

During the collision, A21-29 lost most of its port wing outboard of the

wing

Sadly the pilot of A21-42, WGCDR Ross Fox (CO 75 Sqn), was killed in the accident; his aircraft crashed and was totally destroyed. His body was recovered on 3 August. The 39 year old was a popular commanding officer, ‘a very fine officer and a great bloke.’ On 10 August 1990, all the officers and airmen who had served with 75 Squadron for two years were flown by RAAF Boeing 707 to attend his funeral at St John’s Anglican Cathedral, Brisbane. A party of 82 officers and airmen escorted the colours and bore the casket through the streets to its final resting place.

An AIM-9 missile was mounted on the port wing tip launcher of A21-29 and an analysis of the wreckage showed that this missile had impacted and destroyed the canopy of A21-42. In the process, the dummy warhead of the missile broke up completely and, since the canopy bow was the only component in the area sufficiently stiff to generate the required impact forces, this enabled the exact collision geometry to be determined.

|

||

|

As shown in the Fig. at right, this was essentially lateral with a magnitude of only 50-55 knots. Under the circumstances, it was not surprising that the pilot of A21-42 failed to see A21-29 nor that he failed to eject

|

||

|

It was able to postulate the collision sequence in detail as follows:

|

||

|

There are few distinctive and common traditions which have proved

constant or enduring in most air forces. Among those that the RAAF

observes, none is more emotive than the use of the Missing Man Formation

at a Service funeral. During a fly-over at the church or graveside,

either the formation

The Missing Man Formation is, first and foremost, a custom that is specific to airmen and air forces but when is the use of such a formation appropriate and what are the conventions associated with its conduct?

The historical origins of the practice are quite obscure. Claims are often made that it began during World War I, when units returning from an operation routinely formed up on arrival over their home airfield to allow observers on the ground to see at a glance what the day’s losses had been. If this was a recognised and common practice, personal accounts by airmen of that war are strangely reticent about mentioning it. Another popular myth seems to be that the formation was first flown by the Royal Air Force as a mark of respect for the fallen German ace, Manfred von Richthofen – the famous “Red Baron”. If true, Australian sources would have been ideally placed to record the fact, since the funeral of this enemy airman was conducted by No 3 Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps at Bertangles, France, on 22 April 1918. Remarkably, not a single account mentions the use of the Missing Man Formation, nor indeed any flypast at all.

What is certain is that, after World War I, flypasts and aerobatic displays by aircraft from the armed services became increasingly common during ceremonial occasions and prominent public events. Flypasts at funerals, however, largely remained an informal and private arrangement within the military air services. The first officially recorded Missing Man Formation was flown in Britain in January 1936, during the funeral service of King George V – an honour rendered appropriate by the monarch’s rank as a Marshal of the RAF. In the United States, the first Missing Man Formation appears to have been flown at the funeral of Major General Oscar Westover, chief of the US Army Air Corps, in September 1938. When General Hoyt Vandenberg died in April 1954, he became the first senior officer of the USAF to be honoured with a Missing Man Formation flypast at Arlington National Cemetery, involving six B-47 Stratojets in a V-formation with the second position on the right vacant.

What these instances demonstrated is that, far from being reserved exclusively for airmen at unit level, the Missing Man Formation has been regularly accorded to senior ranking officers. Further blurring the picture is the fact that ‘missing man’ flights have taken on a wide appeal, so that they are no longer the sole preserve of air forces at all. Especially in the United States, private associations and groups also perform Missing Man Formations at funerals of prominent members of the community, not just veterans and during other commemorative occasions. Law enforcement agencies often conduct flypasts at the funerals of policemen killed in the line of duty, while commercial aviation companies also fly tributes at the funeral services of deceased pilots.

This widening of application has produced some further refinement of the standard Missing Man Formation, as in the variant where the flight approaches from the south, preferably near sundown, and one of the aircraft suddenly peels off to the west and flies into the sunset. The trend towards non-exclusivity with aerial salutes has also been evident in Australia, to the extent that when the pioneering female aviator Nancy Bird Walton died in January 2009, a Qantas A380 flew over St Andrews Cathedral at the commencement of her state funeral service in Sydney. Within the RAAF, practice of the Missing Man Formation has largely followed the traditions established by the RAF. A large-scale flypast marked the funeral in 1980 of Sir Richard Williams, regarded as the “Father of the RAAF”, involving four separate groups of RAAF aircraft – without, so far as is known, there being any empty gaps in the formations. At the funeral just four years later of the RAAF’s first four-star officer, Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Scherger, a ‘missing man’ was flown by five RAAF Macchis.

While the Air Force’s most senior and distinguished officers have frequently been accorded the ‘missing man’ honour in Australia, the same tribute has also been paid by individual RAAF units, particularly fighter squadrons, to their past and present members. After Wing Commander Ross Fox, Commanding Officer of No 75 Squadron, was killed in an aircraft accident at Tindal in 1990, a Missing Man Formation was flown by the squadron at his funeral service in Brisbane and in 2006, Wing Commander (‘Bobby’) Gibbes and Wing Commander Richard (‘Dick’) Cresswell, two of Australia’s most accomplished fighter pilots, were both accorded the honour on their passing away. Serving members of the units that these renowned airmen had once led in combat—No 3 and No 77 Squadron, respectively— flew the ‘missing man’ in F/A-18 Hornets.

Although the Missing Man Formation is an aerial salute that works best as an informal tribute by airmen to ‘one of their own’, history demonstrates that the custom has never been confined solely to airmen nor initiated only at unit level. While use at the close personal level of airmen farewelling a respected and cherished colleague is probably closest to the original intention of the gesture, certain historical precedents exist for the Missing Man Formation – in all its variants – to be used for departed senior and prominent figures, even without an Air Force background.

|

||

|

Regular naps prevent old age – especially if you take them while you’re driving.

|

||

|

4 old Radio bods, who went through Laverton at the same time, along with their ladies got together for nibblies on the Sunshine Coast recently. After a few drinks most of the world's problems were satisfactorily solved.

|

||

|

||

| L-R: Trev Benneworth, Maureen Butler (partly hidden), Josie Broughton, Sheryl Benneworth, John Butler, Dave Muir-McCarey, John Broughton. | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Bob Beresford, Rex Koerbin and Garth Simpson.

|

||

|

|

||

|

34 Squadron Mystere 20 VIP aircraft had a windscreen consisting of five laminations of glass, about 1.5 inches thick. The windscreens were secured by about 200 machine screws into the airframe and 'gooped' with fuel tank sealant for pressurisation sealing.

Replacement was usually conducted at the next D servicing, which occurred annually, also, windscreens were replaced when the de-icing/de-misting filament failed, or delamination bubbles appeared. Once the screws were removed, a sledge hammer had to be used to break the seal to remove the windscreen. (Note the impact points all the way around the edge, about 2 inches from the airframe.) |

||

|

|

||

|

A windscreen replacement usually attracted a big crowd, as it was both rare and spectacular to watch a tradesman hit an aircraft with a 14lb sledge hammer, at full swing about 20 times per windscreen.

The 'framie' was under considerable pressure, given that the crowd, which usually comprised most of the unit, including the CO, and a RAAF photographer to record it.

|

||

|

Retirement – twice the husband on half the income.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Peter was a Framie with 9 Sqn from April 1968 to March 1969, shown here at Ben Hoa Base, not long after the Coral Balmoral battle. 9Sqn sent aircraft and personnel in support of Army after the battle. Pete is shown here in front of the 9Sqn maintenance "hangar".

|

||

|

|

||

|

Click HERE for the names in alphabetical order – sorry, not in face order.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

First WRAAF dining in night. Held in the SGTS Mess at Laverton, 08 Feb 1972 (Click the pic for the HD version)

|

||

|

Audrey Webb, Linda Carter.

|

||

|

Trish Newman, Janet Gees, Lorraine Arnold, Leslie Theaker. 1969. |

||

|

|

||

|

You can live without sex - but not without glasses. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

A C-27J Spartan parked alongside a Royal Flying Doctor Service aircraft on the Eyre Highway at Chadwick Roadstrip in the Nullarbor, South Australia.

There are several emergency roadstrips in Australia, bur unlike other countries, those in Australia were not developed as alternate landing areas for the military. Instead these strengthened sections of roadway are for the Flying Doctor aircraft to use when responding to emergency calls.

Back in Oct 2017, delighted motorists witnessed a rare sight on the Nullarbor Plain as a C-27J Spartan and RFDS Pilatus PC-12 made practice emergency landings as part of an integrated emergency services training exercise on the Eyre Highway's Chadwick roadstrip around 100km from the SA/WA border, one of only two emergency road airstrips in South Australia.

Channel 7 News were invited along for the ride to help capture a ‘birds-eye’ view of the activity, the exact location from where the RFDS recently retrieved two motorists critically-injured after their car rolled on the highway.

Click the pic below to see the video taken by Channel 7

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

A hair on the head is worth two on the brush.

|

||

|

At right are the pilot members of "C" Flight No 77 Squadron in early 1971. "C" Flight, although part of No 77 Squadron acted in an independent capacity, within the command of the CO, providing Tactical Photographic Reconnaissance Support to the Army.

A couple, although possibly only one, Single Seat Mirages had been fitted with a KA-56 photo recce camera. The camera replaced the Cyrano Radar in the aircraft nose cone. As well as five pilots they had an air portable photographic recce interpretation facility manned by 3 Specialist Photographic Interpreters, and a second air portable cabin which housed a film processing "Versermat". This facility was manned by a number, of again, specially trained photographers.

They provided airborne photographic support to the ADF on a daily tasking basis. In addition, they were involved in all major ADF training exercises from then on. To get the arrangement underway they initially raced around the various operational Army units scattered around Australia giving then info on their capabilities and getting them on-side.

Standing: Nick Ford, Terry Body, Jim Treadwell (CO). Kneeling: Ken Semmler, John Archer.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Mel Hupfeld, pictured here with the then Wing Commander Micka Gray, Commanding Officer No. 6 Squadron at Exercise Pitch Black 2010.

Mel was born in Sydney on the 7th March 1962 and joined the Air Force as an Officer Cadet in 1980. He finished his training in 1983, won the 'Flying Prize' and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree. He completed a Master of Arts degree in Defence Studies at King's College London in 1997.

During his career he has flown the Dassault Mirage III and McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet flying mainly with No. 3 Squadron. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on the 27th November 2003 for his command of No. 75 Squadron during Operation Falconer and the squadron was awarded the Meritorious Unit Citation.

Mel has commanded several RAAF units during his career, including 75 Squadron, 2 OCU, 81 Wing and Air Combat Group (ACG). He was promoted to Air Vice Marshal and appointed as Air Commander Australia on 3 February 2012. He moved to the Capability Development Group, as Head Capability Systems, in September 2014, before being appointed the acting and final Chief Capability Development Group in 2015 and then Head Force Design in the Vice Chief of the Defence Force Group from 2016.

As Commander ACG, Mel oversaw the phasing out of the F-111, introduction of the F/A-18F Super Hornet and the initial deployments of the Heron Remotely Piloted Aircraft System. He was also Combined Force Air Component Commander for Talisman Sabre 2011 and Joint Force Air Component Commander for domestic operations associated with then US President Barack Obama's visit and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

He was promoted air marshal and appointed Chief of Joint Operations on 24 May 2018.

He succeeded Air Marshal Leo Davies as Chief of Air Force on the 3rd July 2019.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Participants of Exercise Shaken Fury, board a C-17 Globemaster from 36 Squadron before it departs Amberley for the United States. The Globemaster allowed an Australian Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) Taskforce to exercise with international peers in the United States. The contingent of 60 personnel flew to Indiana for Exercise Shaken Fury over 2-9 June.

Air Movements personnel from 23 Squadron loaded 14 tonnes of specialist equipment on the Globemaster along with the Australian USAR Taskforce.

Full House!

|

||

|

|

||

|

Participants of Exercise Shaken Fury, onboard the Globemaster bound for the United States. The successful deployment of the Taskforce highlighted the efforts made by Defence and Australian USAR teams in the past decade to ensure they can be deployed at short-notice. The C-17A and C-130J crews have deployed Australian USAR teams for disaster relief operations in Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, and Vanuatu.

Regular engagement between Defence and USAR teams – such as through training activities like Exercise Shaken Fury – ensure they can be deployed to save lives in future

Loading.

Below, 36 Squadron Loadmaster, Corporal Georgia Harper loads search and rescue equipment on to a Globemaster, prior to it departing for Exercise Shaken Fury. The deployment for Exercise Shaken Fury signified how far the relationship has developed between Defence and USAR Teams, according to Squadron Leader Ben Barber.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Having previously worked as an Air Movements Officer at RAAF Base Richmond, he is now posted as the Movements Flight Commander at RAAF Base Amberley. “Both sides have come a long way since our interactions in 2011, when Air Force deployed USAR Teams following earthquakes in New Zealand and Japan,” Squadron Leader Barber said. “In slow time, we’ve brought USAR Teams to Air Movements Sections at Richmond and Amberley to go through what equipment is safe to fly, and plan how it is palletised to ensure minimal delays.”

Personnel who participated in the exercise. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

You know you’re old when the candles cost more than your birthday cake.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Mick Williams (Elec), Trev Benneworth (Radio), Barry Allwright (Elec)

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

fold

and a 2 ft section of its port tailplane was removed. Control was

retained and the aircraft landed successfully.

fold

and a 2 ft section of its port tailplane was removed. Control was

retained and the aircraft landed successfully.

contains a gap where one aircraft is conspicuously missing or an

aircraft in the formation abruptly pulls up during the flypast and

climbs steeply away while the rest continue in level flight. The gesture

is intended as more than a respectful farewell, for which a simple

flypast would suffice; it is a personal tribute to the person who has

passed away or fallen in combat – an expression that he/she will be

sorely missed.

contains a gap where one aircraft is conspicuously missing or an

aircraft in the formation abruptly pulls up during the flypast and

climbs steeply away while the rest continue in level flight. The gesture

is intended as more than a respectful farewell, for which a simple

flypast would suffice; it is a personal tribute to the person who has

passed away or fallen in combat – an expression that he/she will be

sorely missed.

.jpg)