|

|

|

Radschool Association Magazine - Vol 45 Page 6 |

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

|

Out in the shed with Ted

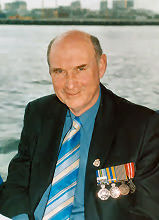

Ted McEvoy.

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

|

|

|

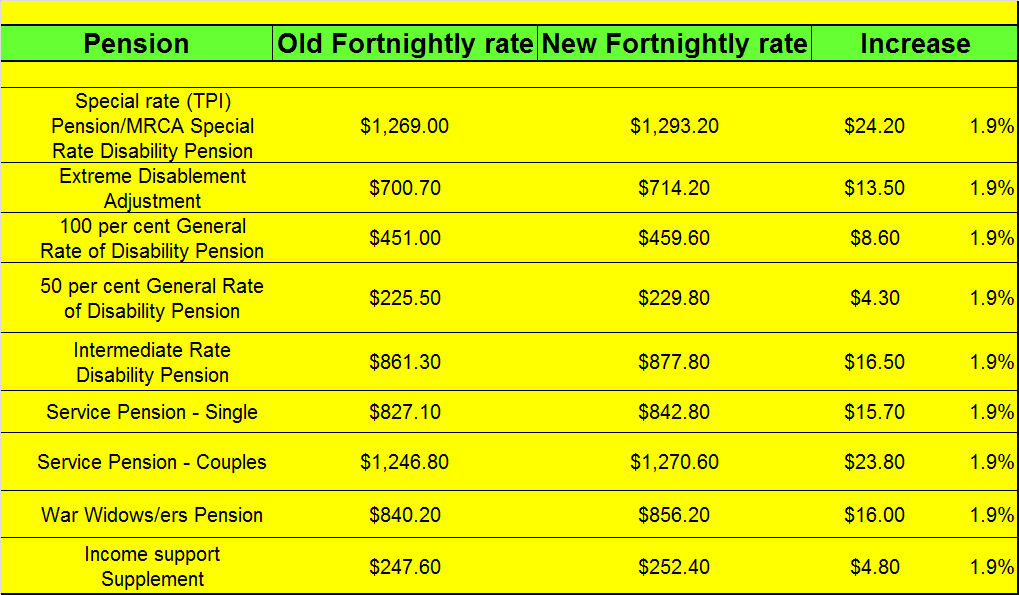

Pensions.

The Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Senator the Hon. Michael Ronaldson, announced new pension and income support payment rates for some 290,000 veterans, their partners, war widows and widowers across Australia would apply from 20 March.

The first full pension payments at the new rates will be on 03 April 2014.

The table below highlights the key changes to fortnightly rates. The next review is scheduled for the 20 September 2014.

|

|

|

|

Disability pensions are not taxed. You do not need to declare it as income in your tax return.

Pensions are indexed twice a year in March and September taking account of changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index (PBLCI) and Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE).

|

|

|

|

Postage.

From 31 March, the price of standard postage stamps in Australia will rise to 70 cents. Some people will be exempt from the increase and can continue to pay 60 cents by setting up a MyPost Concession account. Here’s everything you need to qualify, along with some restrictions to be aware of.

According to Australia Post, approximately 5.7 million Australians will be eligible for a MyPost Concession card. In addition to 60 cent stamps, card holders will also receive concession rates on Mail Hold and Mail Redirection services and a digital mailbox which allows users to pay bills and communicate with selected providers.

To qualify for a MyPost Concession account, a customer needs to hold one of the following concession cards issued by the Federal Government:

Annoyingly, simply owning one of the above concession cards isn’t enough, you need to actively register to the service. The reason for this is that Australia Post needs an easy way to keep track of stamp purchases. Eligible customers who fail to apply for a MyPost Concession card will not receive the stamp discount.

To register for a MyPost Concession card.

You can also pick up and fill out the application form in person at your closest post office.

If/when your application is successful, you’ll receive a free booklet of five stamps and a MyPost concession card within 14 days. You’ll need to present this card at the post office each time you purchase a concession stamp.

It’s worth noting that MyPost Concession posters can only purchase a maximum of 50 concession stamps per year. Naturally, the stamps can only be used for domestic letters and are not valid for parcels or international services.

As you’d expect, it’s against the rules to use a MyPost Concession Account or MyPost Concession Card that doesn’t belong to you. Australia Post reserves the right to terminate the card holder’s account if the terms and conditions have been violated. In other words, don’t lend it out to your grand kids. |

|

|

|

|

|

The President’s Car.

Hours after Pearl Harbour, on December 7, 1941, the US Secret Service found themselves in a bind. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was to give his infamy speech to Congress the next day and although the trip from the White House to Capitol Hill was short, agents weren't sure how to transport him safely. The White House did already have a specially built limousine for the president that he regularly used, but it wasn’t bulletproof and the Secret Service realized this could be a major problem now that the country was at war. FDR’s speech was to take place at noon December 8th, and time was running out. They had to procure an armored car, and fast.

At the time, Federal Law prohibited buying any cars that cost more than $750 ($10,455 in today’s dollars). It was pretty obvious that they weren’t going to get an armoured car that cheap, and certainly not in less than a day so the option was to get clearance from Congress to spend more but nobody had time for that. One of the Secret Service members remembered that the US Treasury had seized the bulletproof car that mobster Al Capone owned when he was sent to jail in 1931.

|

|

|

|

|

|

They cleaned it, made sure it was running fine and had it ready for the President the day after.

And run properly it did. Capone's car was a sight to behold. It had been painted black and green so as to look identical to Chicago's police cars at the time. It also had a specially installed siren and flashing lights hidden behind the grille, along with a police scanner radio. To top it off, the gangster's 1928 Cadillac 341A Town Sedan had 1,360 kilograms of armour and inch-thick bulletproof windows. Mechanics are said to have cleaned and checked each feature of the Caddy well into the night of December 7th, to make sure that it would run properly the next day for the Commander in Chief. The car apparently preformed perfectly, so perfectly that Roosevelt kept using it, at least until his old car could be fitted with identical features (and to this day, Presidential limousines have flashing police lights hidden behind their grilles). When he was told his car’s origin (probably on December 8th as he rode to Capitol Hill), Roosevelt reportedly quipped, “I hope Mr Capone won’t mind.”

The old car was a 1939 Lincoln V12 Convertible built by Ford - wouldn’t you love it?? It was affectionately nicknamed the “Sunshine Special,” supposedly because FDR liked to enjoy the sun while riding around with the top down. Hardly a safe way for a President to meet the masses although the use of presidential convertibles was not eliminated until after JFK’s assassination.

Roosevelt was apparently so attracted to his convertible that he had it bullet-proofed. The Lincoln was now undoubtedly worth more than $750, so the White House got around the spending cap regulation by making a special arrangement to lease it from Ford at the rate of $500 per year. This car was used by both FDR and President Harry Truman until 1950 and is now on display in the Ford Museum in Michigan.

|

|

There is nothing wrong with sobriety in moderation.

|

|

No Comment!!

In a long-awaited fusion between hot-blooded hormones and cold-headed engineering, a Japanese lingerie company has produced a bra they claim will only unlock when the wearer is really n love. Japanese lingerie maker, Ravijour, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary, recently launched their new high-tech bra, the True Love Tester. Featuring embedded sensors and a high-tech clasp, the True Love Tester bra connects to a smartphone app via Bluetooth and only snaps open when it senses that the women is “in love”. According to the designers, the sensors monitor the woman's heart rate and the app analyses the received data to figure out whether or not the woman is in the grip of true love.

You can see their video HERE.

Carer Allowance.

From

1 January 2014 the rate of payment for those who receive a Carer

Allowance was

More than half a million people who receive a Carer Allowance will have their payment increased by $2.80 a fortnight, lifting the basic rate of payment to $118.20 a fortnight. While only a small increase, it does keep the payment in line with the Consumer Price Index.

A good story not known by many.

The only four (4) airplanes Israel had when the war of independence began were smuggled from the Czech Republic. They were German "Messerschmidt 109" and were assembled overnight in Tel Aviv and were never flight tested. This is a short video about their pilots.

Contrary to popular perception the United States' assistance to Israel during the war of independence was quite different. Americans were not allowed to join the fight and an arms embargo had been established and enforced by the FBI.

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the same time Arab armies were very well supplied by the same countries who maintained arms embargo against Israel and of course had great advantage in manpower. You can see the video HERE.

Helicopters.

Who said helicopters weren't maneuverable, have a look at THIS

The Pie.

Bev told me to put the pie in the oven at 120 degrees...........I’m not a very good cook and it took a bit of doing, but being an ex-Radtech I can do anything – see it HERE.

Manure.

There is a very credible story doing the rounds which goes like this:

In the 16th and 17th centuries, everything for export had to be transported by ship. It was also before the invention of commercial fertilizers, so large shipments of manure were quite common.

It was shipped dry, because in dry form it weighed a lot less than when wet, but once water (at sea) hit it, not only did it become heavier, but the process of fermentation began again, of which a by-product was methane gas. As the stuff was stored below decks in bundles you can see what could (and did) happen. Methane began to build up below decks and the first time someone came below at night with a lantern, BOOOOM!

Several ships were destroyed in this manner before it was discovered just what was happening

After that, the bundles of manure were always stamped with the instruction “Stow high in transit” on them, which meant for the sailors to stow it high enough off the lower decks so that any water that came into the hold would not touch this "volatile" cargo and start the production of methane.

Thus evolved the term ' S.H.I.T ' , (Stow High In Transit) which has come down through the centuries and is in use to this very day.

It’s a good story, and over a few beers or around the barby it would seem perfectly credible, but…. whoever came up with it doesn't know shit about "shit."

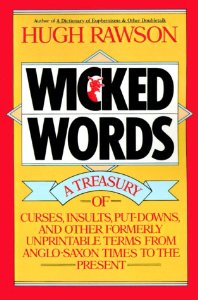

The word is much older than the 1800s and appeared in its earliest form about 1,000 years ago as the Old English verb scitan. That is confirmed by lexicographer Hugh Rawson in his bawdily edifying book, Wicked Words (New York: Crown, 1989), where it is further noted that the expletive is distantly related to words like science, schedule and shield, all of which derive from the Indo-European root skei-, meaning "to cut" or "to split."

For most of its history "shit" was spelled "shite" (and sometimes still is), but the modern, four-letter spelling of the word can be found in texts dating as far back as the mid-1700s. It most certainly did not originate as an acronym used by 19th-century sailors.

Rawson observes that "shit" has long been the subject of naughty wordplay, very often based on made-up acronyms on the order of "Ship High in Transit." For example:

Lastly, all these stories are reminiscent of another popular specimen of folk etymology claiming that the F-word (another good old-fashioned, all-purpose, four-letter expletive) originated as the acronym of "Fornication Under Consent of the King" (or, in another version, "For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge").

Suffice to say, it's all C.R.A.P.

|

|

I couldn’t help but over-hear two blokes in their mid-twenties while sitting at a bar. One of the blokes says to his mate, "Man you look tired." His mate says, "Dude I'm exhausted. My girlfriend and I have sex all the time. I can’t keep up with her, I just don't know what to do." A old bloke, about my age (73), sitting a couple of stools down had also overheard the conversation. He looked over at the two young men and with the wisdom of years says, "Marry her. That'll put a stop to all that!"

|

|

Russia’s Stealth Fighter – the T-50.

Could it outfly and outshoot American Jets?

The T-50 is fast, long-ranged and has fearsome new weapons. Since its public debut about four years ago, Russia’s first stealth fighter has quietly undergone diligent testing, slowly expanding its flight envelope and steadily working out technical kinks. But for all this hard work there have been precious few indications just how many copies of the Sukhoi T-50 Moscow plans to build … and how it means to use them.

Until now!!

Fresh reporting from Aviation Week’s Bill Sweetman, one of the world’s top aerospace writers, offers tantalizing hints regarding Moscow’s intentions for the big, twin-engine T-50, an answer to America’s F-22 stealth fighter.

If Sweetman is correct—and he usually is—the angular warplane with the 50-foot wingspan could be bought in small numbers and used as a sort of airborne sniper, elusively flying high and fast to take down enemy radars and support planes using powerful, long-range missiles.

The T-50's design and apparent weapons options seem to lend themselves to this niche role, which could exploit critical vulnerabilities in U.S. and allied forces and level the air power playing field for the first time in a generation. Especially considering the Chinese are apparently taking the same approach with their own new stealth fighter.

|

|

|

|

At a recent MAKS air show near Moscow, some of the five T-50 test models possessed by Sukhoi made appearances—and manufacturers also showed off missiles that could be fitted into the T-50's voluminous weapons bays or under its wings and fuselage. But Sweetman, wandering the show, detected restraint on the part of the stealth fighter’s boosters. He declared the T-50 exhibits “tamer than some people hoped.”

“I suspect that the fighter won’t be in service for some years, except possibly in the form of a small test squadron,” Sweetman noted. Indeed, Moscow recently pushed back the T-50's first frontline use from 2015 to 2016. But when it does enter service, even in limited numbers the T-50 could have a big impact on rival forces. Scanning the missiles on display at MAKS, Sweetman concluded that the T-50 could be armed with two powerful main weapons:

· a version of the Kh-58UShE anti-radar missile and · the new RVV-BD air-to-air missile.

Both nearly 15 feet long, the Kh-58UShE and RVV-BD can hit targets 120 miles away or farther. The Kh-58UShE homes in on enemy radars; the RVV-BD is for destroying other warplanes.

|

|

|

|

The smaller AGM-88 anti-radar missile and AIM-120 air-to-air missile are the American analogues of the new Russian weapons. Both several feet shorter and hundreds of pounds lighter than their Russian counterparts, the U.S. munitions reflect a specifically American air-warfare philosophy. American stealth jets including the B-2 bomber, the F-22 and the still-in-development F-35 carry relatively small, lightweight weapons with short ranges.

The

B-2's main munition is a 2,000-pound, satellite-guided gravity bomb. For

attacking ground targets the F-22 and F-35 rely on a 500-pound, winged

guided bomb that can glide up to 60 miles under optimal conditions. And

the F-22 and F-35's AIM-120 air-to-air missile,

Left, the MiG-29 (top) and the T-50.

The differences in weapons-loadouts point to the opposing U.S. and Russian concepts for using stealth planes. With the exception of the F-22, American radar-evading jets are not particularly fast and must constantly sneak around in order to use their lighter, shorter-range weapons. This means they need all-around stealth that makes them hard to detect from any angle.

The B-2 can fly thousands of miles but the F-22 and F-35 have modest fuel loads, forcing them to frequently refuel from aerial tankers. The T-50, on the other hand, is apparently being designed to blast through defences in a fairly straight line, relying on front-only stealth features, high altitude, sustained speed and long range to swiftly fire long-reaching missiles at vulnerable targets deep behind enemy lines, without the help of aerial tankers, of which Russia possesses few.

But, this is not to say the T-50 isn’t also highly manoeuvrable when it needs to be. The Russian fighter’s preferred targets might include spy planes, Airborne Warning and Control System/Airborne Early Warning and Command (AWACS/AEW&C) aircraft, tankers and ground-based radars, in other words, all those vital systems that comprise the pricey, high-tech back-end in any U.S. led air campaign. destroy the support systems and their crews and you hobble the enemy’s aerial war effort.

Moscow is not alone if indeed that is its approach to defeating its rivals in a technological battle. China, too, has a new stealth fighter, the J-20. It’s big, heavy and potentially fast like the T-50, likewise concentrates its stealth features up front and also has apparent new weapons. According to the Air Power Australia think tank, the J-20 could be “employed offensively, to punch holes through opposing air defences by engaging and destroying defending fighter combat air patrols, AWACS/AEW&C aircraft and supporting aerial refuelling tankers.”

|

|

|

|

It’s a sound strategy. A 2008 war game conducted by the U.S. Air Force-sponsored think tank RAND pitted F-22s against older Chinese Su-27-style fighters in a hypothetical air battle over Taiwan. After Chinese bombardment of American airfields, just six F-22s were available to fight 72 Chinese jets. Backed by support planes, the defending F-22s got in close and shot down 48 Su-27s, but the remaining Chinese planes managed to power through and destroy six tankers, two AWACS, four P-3 patrol planes and two Global Hawk spy drones, effectively crippling the U.S. force. With no tankers to refuel them, the F-22s crashed for lack of gas despite surviving the missile exchanges.

If older Su-27s firing older weapons could do that, newer and better T-50s and J-20s with longer-range missiles might inflict even more devastating losses with fewer casualties of their own. With these methods, it wouldn’t take many of the new Russian or Chinese jets to make a huge difference in any future air war. So Sweetman’s prediction that the T-50 won’t be built in large numbers any time soon is cold comfort. With its powerful performance and weapons, Russia’s new warplane could tip the balance of power in the air.

|

|

Two Mexican detectives were investigating the murder of Juan Gonzalez. 'How was he killed?' asked one detective. 'With a golf gun,' the other detective replied. 'A golf gun! What is a golf gun?' says number 1 'I don't know’ says 2, ‘But it sure made a hole in Juan.' Sorry Rupe!

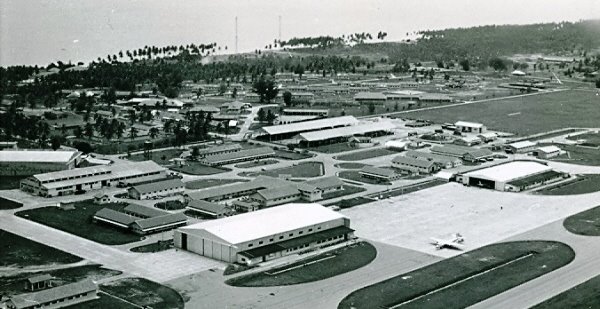

Service at Butterworth Air Base. 1970 – 1989

Prepared in Support of the Rifle Company Butterworth (RCB) Claim for Recognition of Service.

Ken “Swampy” Marsh

Introduction.

Australian service personnel, both Army and Air Force, served at

Butterworth Air Base (BAB) throughout the 1968-1989 Malaysian Communist

Insurgency War. BAB was shared with Malaysian forces who conducted

operations against the enemy from the Base. Despite clear evidence of

Communist activity in the vicinity of BAB and security assessments

concluding the Base could come under attack at any time without warning,

the service of these veterans remains classified as peacetime.

Service at BAB during the Insurgency War is clearly comparable with that rendered in Ubon, Thailand in the late 1960s and at BAB during most of the 1948-1960 Malayan Emergency. In both instances veterans have been granted active service recognition. The peacetime service classification denies these veterans medallic and repatriation benefits that have been granted to others with comparable service and is at odds with established precedents for recognising Australian military service. BAB veterans are being treated unjustly by the government and any delay in rectifying this situation only exacerbates that injustice. It is a betrayal of men and women who pledged their lives to the defence of Australia.

This article presents evidence supporting an outstanding claim by members or an Australian Rifle Company to have their service at BAB recognised for what it was – active service. It provides evidence of Communist activity in the area around Butterworth, Australian service chiefs’ concerns over BAB security, and compares service at BAB during the war with that at Ubon and Butterworth during the earlier Emergency. It also demonstrates the selective use evidence by Government as well as immaterial data to deny the claim.

In many ways Butterworth in the 1970s and 80s was an ideal posting. It offered Air Force families in particular the chance of an overseas posting with additional allowances and on the surface it appeared exotic and peaceful. Because of strict press censorship and the desire of the Malaysian Government not to unduly alarm the local populace or harm the economy, little was said about the existing and serious communist threat. As the local population generally had little to fear from the communists from 1951 on, this decision seems well founded. It is perhaps because of this decision that little has been written on the subject and that nature of the insurgency and its impact on the country is not generally understood.

As this paper demonstrates, Australian personnel on strength at Butterworth Air Base (BAB) during the period of the second communist insurgency were exposed to ‘objective danger’ and as such their service should be recognised as ‘war-like’.

The Threat

The second insurgency commenced on 17 June 1968 when the Malaysian Communist Party (MCP) launched an ambush against the Security Forces in the area of Kroh–Bentong in the northern part of the Malaysian Peninsular. They achieved a major success, killing 17 members of the Security Forces. Kroh-Bentong is less than 80 kilometres in a straight line from Butterworth. In the lead up to the second insurgency the communists had ‘developed new techniques of guerrilla warfare and learned much from the Vietnam War on the techniques of fighting guerrilla warfare.

The modus operandi of guerrillas is hit and run attacks by small groups against much larger military forces. Tactics involve sabotage, ambush, raids and petty warfare. The elements of surprise and ‘extraordinary mobility’ are used to harass the enemy. Following the communist split in the early 1970s Chin Peng’s group ‘sent out “Shock Brigades” – small units which moved south down the peninsula not only to pick off isolated police posts and Security Forces, jungle patrols but also through propaganda to rekindle support for the M.C.P.’ from, their base on the Thai-Malaysian border.

A 1973 report prepared by the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency describes a careful and methodical re-establishment of a very competent communist guerrilla force in North West Malaysia.

“By mid-1968, some 600 armed Communist insurgents … began to move

gradually from inactive to active status under stimulation from Peking.

They moved back across the border [from Thailand], first to reconnoiter

and then

The Peking-inspired revival of the armed insurgency can be fixed to the date of 17 June 1968 when a force of the MNLA for the first time since the late 1950s attacked a Malaysian security force unit on Malaysian territory. This well-trained Communist force numbered about 40 armed and uniformed men, and their ambush was effectively carried out. The evidence is that the revival of the insurgency in mid-1968 reflected from the start considerable military competence: good planning, tactical caution, good execution. CT units were armed and given uniforms in Southern Thailand and were infiltrated skillfully into Malaysian territory with the initial mission of reconnoitering and re-establishing contacts with underground insurgents. Their mission later became that of making selective attacks on Malaysian security force units and undertaking selective sabotage of key installations in West Malaysia. Toward the end of 1968, the number of NMLA – or CT – incursions from southern Thailand gradually increased.

In late 1970, it was solidly confirmed that small groups of CT infiltrators had permanently established small bases for inside-Malaysia operations – a development occurring for the first time since the late 1950s. Later, the base camps were reported to be capable of supporting 40-60 CTs, as they included food caches.

The CTs were still building their units and were not in a phase of general offensive operations. But they did engage in selective strikes against government forces. A major incident involving the mining by CT forces of the main west coast road linking Malaysia and Thailand took place in late October 1969. On 10 December, a strategic installation was hit: a group of CTs blew up the 100-foot-long railway bridge on Malaysian territory about two miles southwest of Padang Besar, Perlis Province, severing for a few days the main railway link between Thailand and Malaysia. Gradually the CTs increased the number of cross-border incursions, their calculation having been to demonstrate their ability to operate on Malaysian territory without suffering extensive combat losses. They wanted to test their own ability to safely infiltrate, to hit important installations and roads, and to move bigger units across undetected. Their planning was careful, the pace deliberate, and the actions generally low risk.

It was believed that by 1971 guerrilla strength had grown to an

estimated 1,200 with another 3,000 cadres in the villages. By 1971, the

Malayan Communists had infiltrated their former village-bases in

Kelantan, Kedah and Perak and were operating along the same

The communist’s 8th Assault Unit with a strength of between 60 and 70 CTs was active in South Kedah, including the area around Kulim, until forced to withdraw by Malaysian security forces in 1978. Kulim is less than 30 kilometres by road from Butterworth.

By October 1974 the MCP leadership had split into three different factions following internal conflicts going back to early 1970. Author Cheah Boon Kheng (above) says that consequently ‘each faction tried to outdo the other in militancy and violence’.

Penang Attacked During ‘New Emergency

Writing for the journal Pacific Affairs summer edition of 1977 Richard Stubbs says:

In September 1975 the Malaysian Prime Minister, Tun Razak, described the recent resurgence of communist guerrilla activity in Peninsula Malaysia as the “New Emergency”. By making the comparison [to the 48-60 Emergency], the Prime Minister clearly signalled the seriousness with which the Malaysian Government viewed the renewal of the communist threat … Not only had there been a number of spectacular terrorist attacks – the bombing of the capital’s War Memorial; the assassination of Perak’s Chief of Police; and the grenade and rocket attacks on the Police Field Headquarters, Kuala Lumpur military air base and several camps in Johore, Port Dickson and Penang – but also, and perhaps more ominously, there had been a steady increase in the preceding three years in the number of police and security force personnel killed and injured. Moreover, the communists seem to have been able to attract recruits and solicit at least some support throughout the peninsula.[15]

It's only when you see a mosquito landing on your testicles that you realise that there is always a way to solve problems without using violence.

Communist Successes

Major Nazar Bin Talib writes: At the initial stage of their second insurgency, the MCP achieved a significant amount of success. Their actions at this stage were more bold and aggressive and caused considerable losses to the Security Forces. These successes were due to their preparation and the training that they received during the “lull periods” or the reconsolidation period after the end of the first insurgency. By this time, they also had significant numbers of new members, who were young and very aggressive. They had learned from the past that they could no longer rely on sympathizers from the poor or village people for their food and logistics.

1971 Major B. Selleck, the OC of the first RCB deployment to Butterworth, reported that on his second tour of Butterworth in June 71: ‘The CT threat was more serious on this occasion, with training activity limited to the Base and Penang. The CTs were very active, blowing up a bridge five miles North of the Base, and daily skirmishes with the local military and police forces.

1974

1975

1987

Malaysian Government Response.

In response to Communist inspired fatal race riots in Kuala Lumpur in May 1969 the ‘Government acted promptly by reintroducing counter-insurgency measures that proved effective during the Emergency years [1948 – 1960]. To guarantee internal security the government maximised the employment of police and provided additional powers to the military to conduct police operations by revisiting the Internal Security Act of 1960. According to Stubbs they ‘gradually reintroduced counter-guerrilla measures that proved effective during the Emergency years.’ These included ‘short-term curfews and food-denial programmes’ in those areas thought to be targeted by CTs.

Major Nazar Bin Talib provided a commentary on the Government’s response to the emergency:

The Government introduced a new strategy of fighting the MCP

[Malayan Communist Party]. It was known as Security and Development, or

KESBAN, the local acronym and focused on civil military affairs. KESBAN

constituted the sum total of all measures undertaken by the Malaysian

Armed Forces and other

The government also instituted other security measures in order to meet the MCP menace, including strict press censorship, increasing the size of the police force, resettling squatters and relocating villages in “insecure” rural areas. By mid 1975, when the MCP militant activities were at a peak, the government promulgated a set of Essential Regulations, without declaring a state of emergency. The Essential Regulations provided for the establishment of a scheme called a ‘Rukun Tetangga,’50 ‘Rela’ (People’s Volunteer Group). The concept of “Rukun Tetangga” (Neighborhood Watch) had made the Malays, Chinese, and Indians become closer together, and more tolerant of each other.

The Government decided against ‘declaring a state of emergency during the second insurgency. The reason was a desire to avoid the fears of the populace (leading to increase in ethnic antipathy) and to avoid scaring away needed foreign investment.’

Crisis in the Malaysian Government.

While the government responded to the emergency effectively, as demonstrated by its final victory, the Communists unsettled the government. According to one of Malaysia’s leading historians, Cheah Boon Kheng:

The communist threat was so serious during the administration of the third Prime Minster Hussein Onn (1976-81) that it was alleged the government had been infiltrated and there was communist influence among UMNO politicians. These allegations arose in the heat of UMNO politics during the party’s annual elections for top posts, and were taken so seriously that two UMNO deputy ministers and several Malay journalists were detained for communist activities.

According to Stubbs, ‘Abdul Samad Ismail (former managing editor of the New Straights Times) had communist affiliations and there were suspicions around Government members, ‘particulalry Abdullah Ahmed and Abdulla Majid, close associates of the late Prime Minister, Tun Razak’.

Contrast to 48 – 60

In June 1948 the murder of three planters in the state of Kedah marked the start of the Malayan Emergency, or first insurgency. From the start the communists looked to the local population for support with food and money and coerced cooperation with acts of murder and violence. By 1951 Chin Peng had recognised that terrorism against the civilian population had backfired and gave a directive that there be no more attacks on civilians or the infrastructure on which they relied for their livelihood and well-being.

In the spring of 1953 Chin Peng, the communist leader, fled Malaya to direct operations from Thailand. This had a devastating impact on the morale of the CTs. To quote Barber, ‘it seems that in many ways the heart had gone out of ‘the cause”.

Before the end of 1953 General Sir Gerald Templer, British High Commissioner to Malaya, expressed the view that the ‘military war’s nearly over’ and that only ‘the political one remains. It was in this year that Malacca was declared the country’s first ‘white area’. A white area was one considered ‘out of the war’. All restrictions such as curfews, rationing and police checks were lifted. By 1955, 14,000 square miles of Malaya had been declared ‘white’. Almost half the country was ‘white’ by the end of 1956 and the communists had been reduced to 3,000 fighting personnel.

By the time the Second Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment arrived in Penang in 1955 it was a white area. After 1955 ‘when it was evident that the communists were on the run and the government had gained the upper hand’, Penang was a popular ‘rest and relaxation centre’ for many Commonwealth troops and support personnel’, many of whom drove from Kuala Lumpur while others caught the overnight train.

At the time the RAAF received ownership of Butterworth Air Base (BAB) in 1957, the Australian government decided to base three operational units there which meant providing accommodation for the families of RAAF members. This despite Malaya being ‘an ‘operational’ zone, albeit a fairly benign one.

RAAF School Penang was established in 1958. ‘Prior to 1958, the Australian commitment at Butterworth was the Airfield Construction Unit. The few primary school-aged dependants of these men attended either the RAF School at Butterworth (which closed when the RAF returned to England in 1960) or the British Army Children's School at Georgetown, Penang. Secondary pupils attended either the British Secondary School at Cameron Highlands or at Singapore.

|

|

|

|

It is worth noting the difference between the above circumstances and those at Johore which remained one of the few ‘black’ areas in 1955. The area was considered too dangerous for army wives and they remained in Singapore, but would occasionally be invited to spend a weekend in Kluang if the police could guarantee the safety of the houses in which they would stay.

By September 57 only 1,360 CTs remained in Malaya, with another 470 over

the border in Thailand. This had reduced to 250 active CTS in the

country by the end of 1958.

While it seems the number of active terrorists during the first insurgency were significantly more in the early years history shows they were effectively defeated early on, with Chin Peng fleeing the country in 1953. The picture painted by Noel Barber in ‘The War of the Running Dogs’ and other sources is of an demoralised enemy being forced further and further into the jungle where they were hunted down by the security forces. From 1953 on, more and more areas were declared ‘white’, meaning they were effectively ‘out of the war’.

By the middle of 1970 there were around 1,600 well trained, bold, aggressive and competent CTs active in Malaysia supported by a greater number of cadres. The CIA estimated that by 1972 this number had risen to around 1800. Richard Stubbs, in his 1977 paper, estimates the number of guerrillas at around 2,600 with Ching Peng’s group being around 2000. It is further estimated that there were approximately 15,000 supporting cadres in Peninsula Malaysia.[48] From the start of the insurgency they targeted security forces, including military establishments, and public infrastructure with their activities peaking in 1975.They successfully conducted terrorist activities from the Thai border in the north to Johore in the south and penetrated areas that had been declared white – and therefore out of the war – since the mid-1950s.

These forces had learned to operate without reliance on the support of the local population, a factor that had contributed to their defeat during the Emergency. Following the surrender of two factions in 1987 around 1300 guerrillas remained active. For almost 20 years they had maintained numbers at a higher level than at any time since the end of 1957 and were not align=justify"; as they had been for much of the first insurgency.

Butterworth Air Base.

|

|

|

|

Seberang Perai (Province Wellesley) where BAB is located, has an area of approximately 700 square kilometres on the mainland of North West Malaysia. It shares its northern and eastern borders with Kedah and its southern border part with Kedah and the remainder with Perak. The communists were active in both these states during the second insurgency.

It was against the background described above of growing communist activity in the states immediately surrounding BAB that a 1971 intelligence assessment of the threat to the Base to the end of 1972 considered it ‘possible, but still unlikely, that the CPM/CTO could take a decision to attack the Base.’ However, it also concluded that; ‘There is definitely a risk that one or more CTs or members of subversive groups could regardless of CPM/CPO policy and/or acting on their own initiative, attempt an isolated attack on or within the Base at any time.’ It was believed these ‘isolated’ attacks could occur at ‘any time’ without advanced warning. Anticipated methods of attack included penetration of the base at night by one or more (up to 20) CTs, sabotage, booby traps, small arms fire or mortar attacks (the CTs were using mortars in early 1974). It must be noted that communist activities continued to escalate after the date of this assessment and that following the split in the early 70s ‘each faction tried to outdo the other in militancy and violence.’

Against this background it seems highly unlikely that an Australian military commander would do anything less than take all necessary precautions appropriate to the assessed level of risk to defend Australian assets and personnel. Documents cited in the Rifle Company Butterworth’s submission clearly indicate an increased concern regarding base security and this is supported by the testimony of members of the Company. Confirmation of the existence of Australian intelligence reports indicating several incidents involving CT and Australian troops is contained in an email sent by a Mr Allan Hawke of the Department of Defence to Mr C. J. Duffield. Armed patrolling and rules of engagement authorising lethal force can only mean one thing – these men were on a combat footing. Any other conclusion denies the evidence.

In the February 2000 Review of Service Entitlement Anomalies in Respect of South-East Asian Service 1955-1975 Major General R F Mohr (See HERE) addressed the matter of ‘objective danger’. Mohr stated:

To establish whether or not an ‘objective danger’ existed at any given time, it is necessary to examine the facts as they existed at the time the danger was faced. Sometimes this will be a relatively simple question of fact - for example: where an armed enemy will be clearly proved to have been present.

However, the matter cannot rest there.

On the assumption that we are dealing with rational people in a disciplined armed service (ie. both the person perceiving the danger and those in authority at the time), then if a serviceman is told there is an enemy and he will be in danger, then that member will not only perceive danger, but to him or her it will an objective danger on rational and reasonable grounds. If called upon, the member will face that objective danger. The member’s experience of the objective danger at the time will not be removed by ‘hindsight’ showing that no actual enemy operations eventuated.

It seems to me that proving that a danger has been incurred is a matter to be undertaken irrespective of whether or not the danger is perceived at the time of the incident under consideration. The question must always be, did an objective danger exist? That question must be determined as an objective fact, existing at the relevant time, bearing in mind both the real state of affairs on the ground, and on the warnings given by those in authority when the task was assigned to the persons involved.

Clearly, in relation to service at BAB, an armed enemy clearly existed. There was an ‘objective danger’. Additionally, evidenced tendered by members of the RCB, ‘rational people in a disciplined armed service’, were ‘told there is an enemy’ and that they were ‘in danger’. According to the precedent established by Mohr, this ‘objective danger’ cannot ‘be removed by ‘hindsight’ showing that no actual enemy operations eventuated’.

Mohr had earlier stated:

I am fully conscious of the provisions governing the award of medals, qualifying service, etc, in Warrants, Acts and guidelines, The point is however, that so many members of the ADF served in South-East Asia during the period of the Review had no idea of the necessity for themselves or their unit to have been ‘allotted’ before they received qualification for a medal or repatriation benefits and now find themselves disadvantaged years later because those who ordered them to do their duty, which they did, took no steps to ensure the required allotment procedures were attended to when quite clearly they should have been.

There is a procedure available for retrospective allotment but this appears not to have been followed in many cases.

It seems unfair that members of the ADF in this situation should be denied the opportunity to put forward for consideration the nature of their service, which would in many cases, amount to operational and/or qualifying service because of this action, or rather lack of action, of their superiors.

This statement has relevance for the RCB claim.

Reasons for Denying Active Service Classification.

Three documents are referred to that provide reasons for rejection of the claim for recognition of ‘war-like service’ at BAB in the period 1970-89:

Lieutenant General Hurley’s letter, in paragraphs 8 and 9, cites the March 1994 Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Defence and Defence Related Awards, that considered ‘service at Butterworth was clearly or markedly no more demanding that normal peace time service.’ The reason for this conclusion is no doubt the comment cited in paragraph 8, ‘Some of these submissions argued that a low level communist threat continued to exist until 1989.’

This ‘low level communist threat’ took 21 years to defeat, compared to the 12 taken to defeat the first insurgency. The communists maintained their numbers throughout the duration of that 21 years at levels in excess of those that had existed in the Malay Peninsula from the end of 1957 (more than two years prior to the end of the first Emergency) and their success in being able to effectively strike at targets in urban areas stands in stark contrast to the 1953 statement of General Sir Gerald Templer that the ‘military war’s nearly over’. This was clearly a dangerous threat that the Malaysian Government considered serious. It was, in the words of the former Prime Minister Tun Razak, the ‘New Emergency’.

While the second document cites a number of documents purported to support the above conclusion those cited by the RCB that clearly indicate real concerns regarding security at the base are not addressed. This evidence should not be discounted.

Paragraph 30 of the second document states that the Ground Defence Operations Centre ‘was never activated due to a shared defence emergency’ and therefore retrospectively concludes that ‘service at Butterworth must have remained as peacetime service subsequent to 8 Sep 1971’. This statement violates the precedent established by Mohr above.

Reference is also made in paragraphs 32 to 36 to the civilian and domestic environment in the Butterworth region. Evidence shows that much of the Malay Peninsula had been declared white by 1955, including Penang which was a popular recreation area for troops serving in Malaya at the time. The author remembers armed police and military roadblocks in Butterworth on more than one occasion during the period July 1977 to January 1980. These would not have been in place in White Areas during the first insurgency.

At paragraph 52 the writer says that the Governor-General cannot make a declaration in regards to the nature of service without prior determination by the Government and a declaration by the relevant Minister. Paragraph 53 then states:

The Minister will only act after firstly considering the informed advice of the CDF, and secondly having obtained the agreement of the Prime Minster. The briefing provided by the CDF would be expected to take into account the impact of collateral financial benefits costed by the Department of Defence, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the Department of Finance and Deregulation, and any views expressed by these agencies.

The document Background Information Paper Nature of Service Classification – ADF Service at RAAF Butterworth, at paragraphs 73 and 80 make reference to cost, with paragraph 80 stating: ‘The cost of including this service in the DVA budget is assessed as significant.’

Compare this with the following enunciated in Principle 10 of the March 1994 Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Defence Awards (CIDA).

Matters relating to honours and awards should be considered on their merits in accordance with these principles, and these considerations should not be influenced by the possible impact, real or perceived, on veterans’ entitlements.

It would appear reference to ‘significant’ costs in the above mentioned document was designed to influence the decision of the Minster and the Prime Minister in violation of this principle.

In a letter to Mr Robert Cross, dated 19 May 2012, Senator the Hon David Feeney (right), Parliamentary Secretary for Defence, states on page 3:

For any ADF service at Butterworth from 1970 onwards to meet the original intent of hazardous service, the service would need to be shown to be “substantially more dangerous than normal peace time service” and “attract a similar degree of physical danger” as “peacekeeping service”. Peacekeeping service generally involves interposing the peacekeeping force, which may be unarmed, between opposing hostile forces. The immediate threat to peacekeepers is by being directly targeted or by being caught in the crossfire of the opposing forces.

Senator Feeney correctly points out that service at Butterworth was not peacekeeping service. ADF personnel were not interposed ‘between opposing hostile forces’. Rather, they shared the facility at BAB with members of the Malaysian Security Forces who were prosecuting a war against a competent and deadly enemy who during the second insurgency successfully attacked military and police targets, including the air base at Kuala Lumpur. Regardless of any security action taken or not taken by Australian Defence Authorities members of the ADF were opposed to an ‘objective danger’ as discussed by Mohr, whether they were being ‘immediately targeted or by being caught in the crossfire of the opposing forces’. This danger existed ‘irrespective of whether or not the danger [was] perceived at the time’ by Australian Forces.

The Minister also notes on page 4 that the ‘Clarke Report accepted that RCB was involved in armed patrolling to protect Australian assets, but concluded that training and the protection of Australian assets were normal peacetime duties.’ The author of this paper has had 20 years military experience, including guard duty at Williamtown and Richmond air force bases. While service rifles were carried on after hours patrolling no ammunition was available and there were no rules of engagement. Further, the author is unaware of sentries at the entrance to any defence establishment in Australia carrying weapons – with or without ammunition. In the author’s five years of service at Butterworth sentries always carried weapons. The Clarke statement does not ring true.

Any fair assessment of the facts can only conclude that Australian personnel at Butterworth during the second insurgency were serving in conditions that meet the criteria for ‘war-like service’. The risk to those personnel serving within the confines of BAB was significantly higher than those who served in the same location from at least the mid-1950s to the end of the 1948 – 1960 Emergency who were granted qualifying service for repatriation benefits as a consequence of that service.

Principle 3 of the CIDA principles states: ‘To maintain the inherent fairness and integrity of the Australian system of honours and awards care must be taken that, in recognising service by some, the comparable service of others is not overlooked or degraded’. This ‘inherent fairness and integrity’ will remain compromised until ADF members serving at BAB during the second communist insurgency are recognised as having participated in ‘war-like service’.

|

|

A Jewish husband and wife were having dinner at a very fine restaurant when this absolutely stunning young woman comes over to their table, gives the husband a big open mouthed kiss, then says she'll see him later and walks away.

The wife glares at her husband and says, "Who was that?"

"Oh," replies the husband, "she's my mistress."

"Well, that's the last straw," says the wife. "I've had enough, I want a divorce!"

"I can understand that," replies her husband, "but remember, if we get a divorce it will mean no more shopping trips to Paris, no more wintering in Barbados, no more summers in Tuscany, no more Jaguar in the garage and no more yacht club. But the decision is yours."

Just then, a mutual friend enters the restaurant with a gorgeous babe on his arm.

"Who's that woman with Moishe?" asks the wife.

"That's his mistress," says her husband.

"Ours is prettier," she replies.

|

|

|

|

|

Sigh..There Goes Butterworth AFB..

The Butterworth AFB will be transformed into a leisure-oriented development under a proposed joint venture (JV). The proposal which is presently being negotiated between the parties was mooted by the JV Company (JVC) to the Government along the lines of a Public Private Partnership concept.

The 407 hectares of land occupied by the base in Teluk Air Tawar – which is about 8km from Butterworth directly opposite Penang Island – would be transformed into “a city of arts and leisure.” The air base will be relocated and reconstructed at a site soon to be identified.

The Government shall pay the

JVC for the new air force base through a land swap at the current market

value of the Government land, which included but was not limited to the

Butterworth AFB has been the main military installation in Malaysia since the early years of World War 2. Initially known as RAF Butterworth, it was a part of the British defence plan for defending the Malayan Peninsula against an imminent threat of invasion by the Imperial Japanese forces during World War II. During the Battle of Malaya, the airfield suffered some damage as a direct result of aerial bombing from Mitsubishi G3M and Mitsubishi G4M bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service based in Saigon, South Vietnam. Brewster Buffalos from the airbase rose to challenge the escorting Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters but were mauled during several of these engagements by the highly trained and experienced Japanese fighter pilots.

The RAF airfield was subsequently captured by units of the advancing 25th Army (Imperial Japanese Army) on 20 December 1941 and the control of the airbase was to remain in the hands of IJA until the end of hostilities in September 1945. After the War, the RAF resumed control of the station and Japanese prisoners of war were made to repair the airfield as well as to improve the runways before resuming air operations in May 1946.

In 1957, the RAF closed the station and it was transferred to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and it was promptly renamed RAAF Butterworth, becoming the home to numerous Australian fighter and bomber squadrons stationed in Malaya during the Cold War era.

The Australian fighters and bombers played a significant role in providing air support during Operation Firedog during the Emergency and later was part of Commonwealth air defence contribution against the might of the then Angkatan Udara Republik Indonesia (AURI now TNI-AU) during the Konfrontasi.

From 1970′s onwards, the

airbase played an important part in supporting Malaysia’s fight against

the communist threat. Being the northernmost and nearest base to

communists hotspots especially those near the Thai-Malaysian border, a

dark episode looms over the

The RMAF Butterworth, as the airbase was known back then, was also the birthplace of Malaysia’s jet fighter units namely No 11 Sqn with CAC CA-27 Sabres in 1967. During Ops Gubir, F-5 fighters from the airbase were launched to pound communist hideouts in Gubir, Kedah. This feat was later repeated again decades later, when two Hawk and five Hornet jets from No 15 Sqn and No 18 Sqn were deployed to Labuan AFB from the airbase and took part during the opening hour of Ops Daulat in March 2013.

After relinquishing its control over the airbase to the RMAF in June 30, 1988, the RAAF maintained an infantry company (known as Butterworth Rifle Company) and a detachment of AP-3C Orions from No 92 Wing. The Five Power Defence Arrangement (FPDA) also has an Integrated Air Defence System HQ (IADS HQ) located at the airbase.

It is unknown whether these factors have been considered in the proposed development plan as Butterworth AFB has a long and rich history and heritage that is significant to Malaysia. You can read more on Butterworth AFB’s history HERE, HERE and HERE.

|

|

While shopping for holiday clothes, my husband and I passed a display of bathing suits. It had been at least ten years and twenty pounds since I had even considered buying a bathing suit, so I sought my husband's advice. 'What do you think?' I asked. 'Should I get a bikini or an all-in-one?' 'Better get a bikini,' he replied. 'You'd never get it all in one.'

He's still in intensive care.About these ads

|

|

Blessed are those who are cracked, for they are the ones who let in the light!

|

|

|

|

Ok, Ok!! – I’m going back to my room now!!

|

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

increased in line with the CPI, so how much extra will you

receive?

increased in line with the CPI, so how much extra will you

receive?

12 feet from tip to

tail, has a range of probably only 50 miles or so, although the precise

distance is classified. Remarkably, no American stealth jets can carry

anti-radar missiles like the T-50 probably can.

12 feet from tip to

tail, has a range of probably only 50 miles or so, although the precise

distance is classified. Remarkably, no American stealth jets can carry

anti-radar missiles like the T-50 probably can.

(government) agencies to strengthen and protect society from subversion,

lawlessness, and insurgency which effectively broke the resistance.

(government) agencies to strengthen and protect society from subversion,

lawlessness, and insurgency which effectively broke the resistance. General

Sir Harold Briggs (left) arrived in Malaya in 1951 and shortly

thereafter developed and implemented the ‘Briggs Plan’. This ‘brought

about a serious food crisis for the insurgents because it isolated them

from their food suppliers – the Chinese squatters living on the jungle

fringes who were forcibly removed by the government and transferred to

fenced-in ‘new villages’ that came under government control’. This,

along with other military initiatives, saw the guerrillas driven

‘‘deeper and deeper into the jungle’.

General

Sir Harold Briggs (left) arrived in Malaya in 1951 and shortly

thereafter developed and implemented the ‘Briggs Plan’. This ‘brought

about a serious food crisis for the insurgents because it isolated them

from their food suppliers – the Chinese squatters living on the jungle

fringes who were forcibly removed by the government and transferred to

fenced-in ‘new villages’ that came under government control’. This,

along with other military initiatives, saw the guerrillas driven

‘‘deeper and deeper into the jungle’.

407ha of land where the existing Butterworth AFB is situated. The land

swap deal means that the Government needs not fund the cost of

relocating and reconstructing the air force base and also secured it the

opportunity to participate in the redevelopment of the land via its 30%

interest in the JVC.

407ha of land where the existing Butterworth AFB is situated. The land

swap deal means that the Government needs not fund the cost of

relocating and reconstructing the air force base and also secured it the

opportunity to participate in the redevelopment of the land via its 30%

interest in the JVC. airbase when a Sikorsky S-61A-4 Nuri helicopter operated by No 3 Sqn was

shot down by the communist terrorists over Gubir with the loss of all

hands on-board.

airbase when a Sikorsky S-61A-4 Nuri helicopter operated by No 3 Sqn was

shot down by the communist terrorists over Gubir with the loss of all

hands on-board.