|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

|

||

|

|

||

|

Pedro’s Patter.

Excerpt from Jeff’s book – Wallaby Airlines.

Bombs and Bullets.

January – February, 1967

My return from Malaysia and Singapore was harder this time than after the last trip to Butterworth. Being reunited with Robyn, even for a short time, made coming back almost worse than coming here in the first place. Leaving Robyn in Singapore was just like a re-run of the previous July. It was a gut-wrenching experience. Our wonderful ten days were more like a second honeymoon than a holiday. I found it hard to settle down again to the daily grind of Vietnam without the love and companionship I had rediscovered, even so briefly.

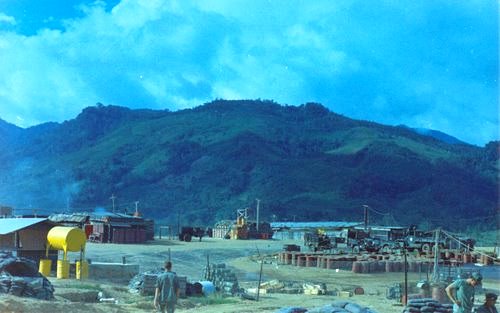

I struggled to get into the routine of things again, but of course I soon did. In no time at all I was back on detachment with my old partner of many adventures, John Harris. We were given a special assignment. Saigon TMC tasked us to carry out photographic surveys of a number of airstrips in the I Corps and northern II Corps Military Regions. Two photographers and their equipment, both from a USAF unit based in Saigon, were assigned to accompany us. TMC organised a briefing to familiarise us with the task so we could map out some sort of itinerary.

Our plan was to overnight in Danang and Pleiku, hopping from strip to strip in between. I won the toss for the first day’s flying. We set off for Danang along the coast, planning to look at Duc My, Dong Tre, Tra Bong and Tien Phuoc along the way. Our brief was to fly low along each strip, then climb out to 2000 feet, make a ‘half dumbbell’ (90°–270°) turn, and descend back towards the runway on a dummy approach. The photographer, strapped in securely near the open cargo door, took his pictures directly behind us.

This procedure, while very effective for photography, maximised our exposure to sniper fire. We kept our fingers crossed.

Duc My, a sleepy little town a bit like Camau in the Delta, slumbered on during our manoeuvres, but at Dong Tre, there was a skirmish going on. Vietnamese Skyraiders were bombing and strafing a VC stronghold on the side of a nearby hill. Keeping well clear of the action, but with one eye on the Skyraiders, which were causing little incandescent puffs on the jungle-covered hillside as their phosphorus-tipped rockets thudded home, I set the aircraft up in the photographic pattern.

The easterly approach was over a clear part of the valley, but climbing out to the west, we passed over a patch of thick jungle. As we turned to descend back towards the strip, we heard several loud reports. Our USAF cameraman yelled through the intercom: ‘Some sonofabitch just shot at us!’ After landing, we checked the aircraft thoroughly, but found nothing. I was still a ‘virgin’.

Having been there in the right-hand seat with Dick Brice I was looking forward to my first landing at Tra Bong. Its 1000 feet looked incredibly short, but I managed quite a good approach. I had just lowered the nose wheel onto the runway, congratulating myself on a good landing, when a large black dog ran straight across our path. My heart nearly stopped in surprise. Somehow we missed it. I remember the incident in particular, as this was one of the very few dogs I ever saw in Vietnam. (According to squadron gossip, all Vietnamese dogs had long ago been killed and eaten.)

The airstrip was wedged in by hills and had a road running parallel to it. After a look at Tien Phuoc, a fairly challenging, rough-and-ready strip in the foothills, we headed for our overnight stop at Danang. The base had become much busier since our last visit, more like Tan Son Nhut. There was a new parallel 10,000-foot runway, and many more aircraft. We were told to orbit over the bay while gaggles of jets arrived and departed. When we found a gap in the traffic, I set the aircraft up for a high-speed penetration into the traffic pattern to avoid any further delays, decelerating and extending the undercarriage at the last possible moment.

Taxiing in to the ramp, we noticed groups of aircraft parked inside lines painted on the tarmac. They were the latest fighter-types in photo-reconnaissance configuration, and the new ‘hush-hush’ C-130s, a couple of which I had seen at Nha Trang. The latter were painted in black and green camouflage, instead of the usual brown and green, and had a strange contraption on the nose, which gave them the appearance of huge praying mantises. We found out later that these highly secret aircraft were used to snatch people or objects from the ground in rescue or covert operations (called a Fulton Recovery System). The gadget on the nose of the aircraft concealed pulleys, a cable and a hook. The cable could be played out to allow the hook to engage another cable strung between two poles on the ground. A person or a package could be snatched and reeled in to the low flying C-130.

I had no idea what the painted lines on the tarmac meant, so I headed for our old parking spot. A myopic-looking military policeman in a hard hat appeared from nowhere, pointing his M16 directly at us. Dubious about his intentions, I stopped the aircraft and opened the side window. ‘I’ll shoot you dead if you cross that line’, he yelled. Had he not heard of the famous Wallaby Airlines? His attitude seemed rather extreme, but his eyes looked very close together, so I decided to park somewhere else.

Next day, John climbed into the left-hand seat, and we headed north. I had not been north of Danang before so the day held a lot of interest. Our first photographic sortie was at the airfield known as Hue Citadel to distinguish it from the military base at Hue Phu Bai. Situated on the Perfume River, the city of Hue is 45 miles north-west of Danang, and from the early 19th century until 1945 was the capital of the whole of Vietnam under the Nguyen emperors.

The ‘new’ city of Hue was built across the river from the old moated citadel, whose high walls contained the Imperial Enclosure. The Imperial Enclosure was a citadel-within-a-citadel, built as a final barrier to the Forbidden Purple City, the private residence of the emperor. Fortified gates and bridges across the moat allowed access to the citadel from the outside world. Under other circumstances, we could have spent hours exploring this fascinating place. At this time, the citadel’s timeless beauty was still intact, its delicate roofs and gargoyle-encrusted walls reflected in the calm waters of the ornamental moat.

We were lucky to see it as it was. On 31 January 1968, during the Tet Offensive, Communist forces overran the citadel city. Twenty-five days of vicious hand-to-hand fighting took place with heavy casualties on both sides before air, naval and ground bombardment finally drove the NVA out. In the process, over 50 per cent of this priceless ancient city was reduced to rubble and many of the civilian population massacred.

Much later, in the final assault on the South, street fighting would destroy the remainder.

We went on to Ba Long, 10 miles from the Laotian border and 15 from the DMZ. When we landed, there was not a soul in sight. The area was dead flat and treeless, being on a wide coastal plain bounded by distant hills and the South China Sea. All around us, long grasses rippled in a light breeze. It was so quiet and deserted it was eerie. Although the airfield was supposed to be secure, I felt uneasy. Still no one appeared, so we wasted no time starting up and getting away.

From Ba Long, we went to An Hoa, on the Thu Bon river 20 miles south of Danang, then on to Ha Thanh, short with a hump in the middle, inland from Quang Ngai. Each time, we flew our ‘dumbbell’ pattern, the photographer clicking away out the back of the aircraft.

Our final stop for the morning was Ly Son on an island called Cu Lao Re, 15 miles off the coast from Quang Ngai. The island, only a couple of miles long and a mile wide, looked more like a South Pacific hideaway than a government outpost. The only hazard here would be sunburn, I thought. It seemed like a good place to spend the war if you had a choice, until we found out it was also a leper colony.

After lunch, John and I swapped seats again for the flight to Pleiku via Dak Pek, Dak Seang and Plei Me, all familiar ports. Late in the afternoon, the weather began to catch up with us. Heavy cloud build-ups covered the area around Pleiku, making a GCA necessary. On finals, the GCA controller prattled on reassuringly: ‘Wallaby Zero One, you are number one in the pattern, on glide path, a few feet right of centre line, change heading five degrees left to two six zero’. And so on. Suddenly we entered a momentary break in the cloud, and I was conscious of a large shadow blotting out the patch of sunlight. Looking up, I saw an Air America C-46 pass directly in front of us about a hundred yards away, without any warning. My blood ran cold, then hot with anger. I had a fleeting mental picture of 50,000 pounds of tangled metal falling out of the sky had we been a few seconds earlier. This outrageous incident was not the controller’s fault, but poor airmanship of the part of the C-46 pilot barging through instrument approach airspace on a so-called ‘special VFR’ departure. This was the first time I had been at risk of a collision on a GCA, which was supposed to be a controlled precision approach separated from all other traffic.

This incident, and a few other experiences, added strength to my belief that flying in visual conditions, at low level if necessary, was always safer than ‘going Popeye’ in this crazy environment.

Next day we headed back towards Nha Trang. Buon Blech and Buon Ea Yang were our first two stops. The disturbed earth around the new membrane airstrips was the familiar deep ochre colour of the western highlands which turned into a sticky quagmire when wet. Further on was Lac Thien, only 980 feet long, taking its name from a nearby lake. We later heard that the two GIs who met us here had been ambushed and killed on their way back to the camp.

En route to Saigon again, our two intrepid photographers presented us with a record of flying hours for the trip which they wanted us to certify, since the flying counted towards the award of a US Air Medal. Each 100 hours flying meant another medal. They already had two or three each, and confided that they felt much better about accepting them after a trip like this rather than by logging passenger time on courier flights. Perhaps the two medals we got for our whole 12 months tour here were worth something after all.

After the culinary delicacies I had enjoyed on my R&R, it was especially hard to stomach the food back at home base again. On detachment, the menu was much better as the Americans at Danang and Nha Trang seemed to be able to wangle fresh meat out of the system. But back at Vung Tau, the return to etherised (preserved) eggs, American frozen ham steaks and the never ending supply of lima beans was more than my system could endure. I could no longer raise any interest in breakfast, and dinner was fast losing its attraction.

John and I decided to do something about it. When we returned from Danang, we organised a squadron ‘dine out’ downtown. We chose the Neptune, where I had been earlier with Dick Brice. It was a presentable-looking upstairs open-air restaurant with a view of the lights of the town, such as they were. We had no idea what the kitchen was like, nor did we care. The visible part was satisfactory. The menu was in French and very comprehensive. The waiters ponced around in white jackets and bow ties, and the wine list was long and not too expensive.

We luxuriated.

The evening was a great success—even the CO agreed. (He came with us, as Stu Spinks (right) the squadron wag said, ‘to keep us on the straight and narrow’. It was true that we all walked back to the Villa together like a Boy Scout troupe.)

After this we decided to make dine outs a regular event. The funny part was that each restaurant we patronised seemed to be the subject of a military health and hygiene check the following week, and placed out of bounds by our medical officer. Even so, no one seemed to mind, and there were no outbreaks of terrible diseases.

It was not only the food that was making me sick. One night in the bar, I found myself drinking with a group which included a visiting pilot from ‘Guns a Go-Go’, the cowboy euphemism for a US Army Chinook gunship squadron that operated in cooperation with our own No 9 Squadron. He was revealing the VC’s latest ruse for infiltration into the Delta:

“Man, you wouldn’t believe what those sons of bitches are up to. They come sailing up the rivers from the open sea in sampans, with women and kids on the upper decks just to confuse us. Course, we’ve got to shoot hell out of ’em. Far as we’re concerned, they’re all VC, and the only good VC’s a dead ’un.”

Was he for real, or just shooting off his mouth? Of course, I had heard similar stories from the fighter pilots at Danang and I suppose that by carting bombs and bullets around the country, I was doing as much as anyone else here to bring death and destruction on the Vietnamese people. But somehow, my role did not seem so bad, and I was not conscious of any civilians dying due to anything I did.

Sometimes I got the feeling we were on the outer fringe of things up there. We were like general roustabouts who, in the course of getting supplies into out-of-the-way strips in bad weather sometimes got shot at and hit. Chopper pilots flew lower and more often into insecure areas, usually with armed back-up. But our blokes on the average seemed more ‘normal’, for want of a better word. They did their job without fuss or bullshit. OK, it was not as dangerous, though statistically there was always that chance that a stray round might hit flesh and bone rather than metal.

It was becoming harder to maintain enthusiasm about this war, and with the cause, especially since it was obviously ‘business as usual’ back home. I felt very sorry for the Nashos (National Servicemen), dying by the dozen, and for the American draftees. How many promising lives would be ended prematurely?

As if to resolve my conflict, the VC intervened in my life in a very personal way.

On 23 January I was flying down the Delta with Stu Spinks on a 406 mission. The weather was foul. A line of thunderstorms stretched right across the Delta, as it often did in the wet season, just the other side of Long Xuyen. Finding no gaps in the wall of cloud, we climbed to 16,000 feet and finally got through a relatively clear patch. Toward An Thoi, however, another wall crossed our path. There was no way around or over it this time, and no guarantee we would find An Thoi, which was out of range of all navigation aids, even if we got through.

Furthermore, we had barely enough fuel after all our diversions to make the round trip to Camau, our fuel stop. I decided to head straight for Camau now and, therefore, back towards the storms. As luck would have it, Camau was sitting right underneath a large rain shower. Since Camau had no navigation aids, the only way in was to make a low-level run from about 15 miles out, during which the bulky Caribou would be an easy target.

As a longstanding member of the ‘Chicken Club’, I decided to make it hard for any unfriendlies who might be waiting for us. I set climb power, and pushed the aircraft down to just a few feet above the terrain. As we flashed across the rice paddies 40 knots faster than usual, we heard a volley of automatic rifle fire followed by a ‘thunk’ from the rear of the aircraft. Stu shouted: ‘The bastards are shooting at us!’, almost in surprise. I felt no emotion at all, concentrating as I was on avoiding obstacles. Barry Ingate, our crew chief, however, was quite outraged. A week away from completing his tour and only now taking his first hit, he clearly resented this violation of his ‘virginity’. Grabbing his rifle, he threw himself flat on the cargo ramp and emptied his magazine at the retreating, black pyjama-clad figures. Whether any of his rounds found their mark is doubtful. But I guess he felt better.

On the ground at Camau, we found a neat, round hole through the rudder, about two inches in front of the trailing edge. Forty knots slower and the hole might have been in the cabin. Our Vietnamese passengers, forgotten in the drama, stared wide-eyed at the hole, drawing their own conclusions. We pacified them as well as the language barrier would allow, and continued on our way.

Now that the spell had been broken, I half expected disaster on every

mission, and flew everywhere at either several thousand feet, or treetop

height, depending on circumstances. Even though I felt better down low,

I am not sure the passengers did. I remember looks of alarm on several

military faces when, due to low cloud one morning, I flew the courier

low level from Vung Tau to Luscombe (Nui Dat). I descended over the bay

towards the mars

When snipers caught up with me again, I did not even realise what had happened until afterwards. On the first occasion, I was inbound to Dak Seang from Pleiku, again with Stu Spinks. After landing, we noticed a hole clean through the starboard aileron. It was obvious from the shape and size of upper and lower holes that the round had been fired from the ridge line above the camp, probably as we turned onto finals. The Aerodrome Directory warning, ‘occasional sniper fire from hills’, meant something after all.

The other time, after a trip to Butterworth in Malaysia of all places, I found a neat hole in one blade of the left-hand propeller. Since we had made only one take-off and one landing in Vietnam on the trip, we knew the bullet came from Vung Tau. I no longer rubbished those pilots who circulated stories about a sniper who sat all day in the swamp near the base waiting to take a pot shot at aircraft in the GCA pattern

|

||

|

I saw my mate Charlie this morning, he's only got one arm bless him. I shouted - "Where you off to Charlie?" He said, "I'm off to change a light bulb." Well I just cracked up, couldn't stop laughing, then said, "That's gonna be a bit awkward init?" "Not really." he said. "I still have the receipt."

|

||

|

Crash of Caribou A4-264.

On the 4th July 4, 1986, Caribou A4-264 crashed while in a landing phase at Camden airport, about 60 klms south west of Sydney. Fortunately, no one was injured however, the damage was so extreme the aircraft was beyond repair.

A4-264 had a checkered life, delivered to the RAAF in May 1968, it spent time with 38 Sqn Det "A" in PNG, where in July 1971, it overran the end of the strip at Tufi, a small settlement on the northern coast of PNG, due east of Moresby. There were no injuries. In this instance the aircraft ended up in a valley and was manually hauled out back onto the airport by about 200 local people from around the district.

After repair, it returned to Australia and then spent time, painted white and wearing UN markings, with UNMOGIP in Kashmir. It rotated back to Australia in 1976 and in 1978 went to Pearce after which it returned to 38Sqn at Richmond.

It finally crashed at Camden NSW while landing and ended up at Richmond as a Fire Fighting aid.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Blonde 1: Don't tell anyone but bees really scare me. Blonde 2: Don’t worry, the whole alphabet scares me.

|

||

|

The C-27 Spartan

Australian Aviation recently visited 35 Sqn at Richmond to learn more about the RAAF's Caribou replacement, the C-27 Spartan. You can read their story HERE.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Wellington Airport, NZ. Control tower to be decommissioned after 60 years.

Anyone who has been to Wellington in NZ will know that the airport Control Tower is situated in the suburbs, near the airport.

|

||

|

|

||

|

It is thought to be the only one in the world built on a residential

street - it even has its own letter box, but after nearly 60 years

controlling the capital'

Built in the suburb of Kilbirnie, in 1958, 'The Grand Old Lady of Wellington' will be replaced by a new control tower.

Its unique location among the houses in the hills on the western side of the airport gave it a perfect view over the runway, however, the premises has reached the end of its useful life.

The tower had served Wellington well over the last six decades, surviving major storms and keeping travellers and flight crew safe in the capital's notorious winds. It was estimated the staff at the tower had watched over 7 million flights during its tenure.

The Airways staff who had spent their entire careers in the tower, as well as many other people, will be sad to see it wound down.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The old Tower building.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The New Tower building, “The leaning tower of Wellington?”.

|

||

|

The new tower at Lyall Bay, which has been build to “lean into the wind” is also located outside the main airport boundary, near a retail area carpark which is owned by the airport. The new tower was a leap forward in design from the old tower: "It's likely one of the most resilient buildings in the country." It has base isolators to limit earthquake damage and was designed to withstand a one-in-2000-year tsunami.

The old tower will eventually be sold and it is thought it would make a "pretty good house" for aviation enthusiasts.

|

||

|

I woke to go to the toilet in the middle of the night and noticed a burglar sneaking through next door's garden. Suddenly my neighbour came from nowhere and smacked him over the head with a shovel killing him instantly. He then began to dig a grave with the shovel. Astonished, I got back into bed. My wife said "Darling, you're shaking, what is it?" "You'll never believe what I've just seen!" I said, "That bloke next door has still got my bloody shovel."

|

||

|

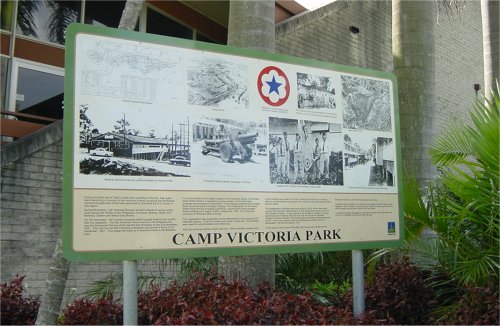

Camp Victoria, Brisbane.

About a klm or two from the centre of Brisbane is the Victoria Park Golf Course. Most Brisbaneites know where it is, just over the road from the EKKA, but not a lot know of its history.

|

||

|

| ||

|

The club was formed in 1931. During the latter half of 1941, events unfolding in the South East Asia region were becoming a concern to the American forces occupying the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur was appointed to command the US Forces in this region.

During November 1941, General Brereton arrived in Manilla to survey a ferry route across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines, via Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Por Moresby, Darwin thence onto Manilla.

Then Pearl Harbour happened and the US was also in the war.

The first American forces to arrive in the Brisbane area was the Pensacola Convey which had left San Francisco on the 21st November 1941. This convoy had been diverted to Brisbane and arrived at noon on the 22nd December, 1941 thus began the build up of American Forces in the Brisbane area.

|

||

|

|

||

|

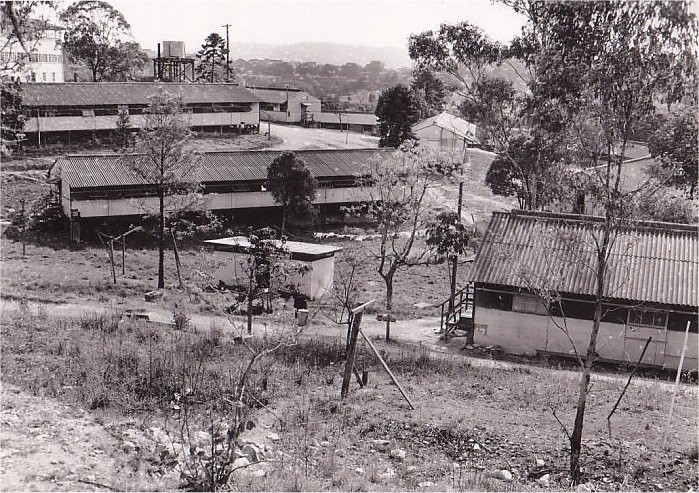

To accommodate all the logistic support for the US forces in the South

West Pacific theatre of operations, a large complex of pre-fabricated

buildings was erected at the Victoria Park Golf course. These buildings

stretched from Herston Road across the park to Gregory Terrace. The

Headquarters o

USASOS was responsible for the logistical support and the supply of all materials necessary to run the war, from the humble razor blade to a battle tank. The buildings were used for accommodation of the troops and also as office blocks.

After the US forces left for PNG, the RAAF took over the complex and when the war ended and peace broke out, many of the buildings were used by the Qld Housing Commission for returning servicemen.

Over time the returned men were settled elsewhere and the WW2 buildings were either sold off or dismantled with the last going in 1971. At the same time, the fairways were realigned to accommodate proposed road works and a new Club House was built.

Today the Golf Complex is renowned as one of Australia's best public United States Golf Association (USGA) rated golf courses. If you’re into golf you can see further information HERE.

|

||

|

Two hands on the throttles.

If ever you get the chance to watch the pilot/co-pilot at work during

the take-off phase, you’d see both persons with their hands on the

throttles. If so, you, like us, would wonder why that is. Is this a

security thing, is this to stop a suicidal pilot from pulling power and

ploughing everything into the drink,

Well, no, neither of those.

The reason is pretty simple really. The pilot is primarily responsible for all aspects of flight, including take-off, cruise, and landing. On take-off he lines up the aircraft, sets the airframe configuration and thrust level (large aircraft rarely use full power on take-off) then when ready, releases the brakes and commences the take-off roll. At this phase, both pilot and co-pilot have one of their hands on the throttle levers. As the aircraft approaches V1 (the speed where take-off cannot be aborted), the pilot takes his hand off the throttle levers and puts both hands on the “wheel” to rotate the aircraft. The co-pilot keeps his hands on the throttles to ensure the levers don’t creep back reducing power.

Then, once the aircraft is settled into its climb-out phase, the co-pilot takes his hands off the throttles and both commence their take-off check-list.

Another reason the co-pilot does this is to be in a position to act immediately if there is an emergency. If the take-off has to be aborted, the pilot will need two hands to control the aircraft on the ground – and while he’s doing that the co-pilot will pull the power.

The reason is that simple, but, technology is steadily making that practice redundant. Most modern jet transport aircraft have a switch called TOGA – which is “Take Off, Go Around”. This is part of the new “Auto-Throttle” facility. It works like this:

Once an aircraft has lined up, the pilot increases the engine power. He then presses the TOGA switch by pushing the thrust levers to TOGA on Boeings or to TOGA or FLEX detent on Airbuses and the engines then increase to their computed take off power. Modern aircraft flight management computers will determine the power needed by the engines for take off, based on a number of factors such as runway length, wind speed, temperature, and most importantly the weight of the aircraft. In older aircraft these calculations were performed by the pilots before a take-off. The advantage of having such a system is the ability to reduce wear and tear on the engines by using only as much power as is actually required to ensure the aircraft reaches a safe take-off speed.

With the computer taking control of power settings and with yokes replacing wheels, this practice seems to be a thing of the past. The TOGA system works a lot like the cruise control system in your car, if the pilot hits the toe brakes on take-off (aborts the take-off), TOGA automatically brings the engines into reverse and raises the spoilers and auto-brake kicks in.

You know it makes sense!

|

||

|

The doctor said, "have you been drinking enough fluids lately?" The bloke said, "that’s all I do drink".

|

||

|

DVA Queensland - Christmas party – 2018.

The Queensland division of the DVA held their annual Christmas get together on Thursday the 6th December. DVA has been holding these Christmas “get-togethers” for many years and, apart from enjoying the odd prawn or six, it is an excellent opportunity for Ex-Service organisations to meet with and discuss any problems they might have with some of the senior DVA people. "

This year’s guest of honour was the very approachable Craig Orme DSM AM CSC (right). Craig is the Deputy President of the Repatriation Commission within DVA which he joined in 2015 after leaving the ADF. He normally works out of Canberra.

Craig has a military background, having spent 37 years with the Australian Army, retiring with the rank of Major General (AVM in the real money). Craig was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) in the 2016 Australia Day Honours.

During his military career, his operational experience included deployments in Malaysia, Iran, Kuwait and US Central Command, as well as in the Middle East and Afghanistan. The DSC acknowledges his distinguished command and leadership in warlike operations as Commander Joint Task Force 633 on Operations SLIPPER and OKRA from September 2013 to December 2014.

Within DVA, he has been heavily involved in work to introduce online claims forms, develop a single dispute resolution pathway for claims, update IT systems and reduce claims processing times.

Craig made himself readily available and offered a sympathetic ear to everyone at the party and assured everyone that as he was a Vet himself, he had the interests of all Vets top of mind.

Craig and all the Ex-Service Organisation members were welcomed to the afternoon by the Queensland Deputy Commissioner, Leanne Cameron.

|

||

| Craig Orme, Leanne Cameron. | ||

|

|

||

|

Leanne’s public service experience spans a range of policy, service delivery and project management roles. She joined the Department of Veterans’ Affairs in 2001 as a graduate, working in Human Resource Planning and Industrial Relations before transferring into Health Policy, where she worked until she left the Department in 2009. After a couple of years in the private sector and local government, she returned to DVA, taking up a position in the Health team in Brisbane.

Prior to her current appointment, Leanne was the National Director for the Veterans’ Access Network, and a year or so back the Deputy Commissioner for South Australia and the Northern Territory. She was responsible for implementing the on-base advisory service, and the Department’s national contact centre. She was also responsible for Community Development, FOI and Case Coordination.

In 2010 she undertook a six month exchange program with Veterans’ Affairs Canada, working on a transformation agenda for their health program. In 2011 she received a Secretary’s Award as a member of the small team responsible for responding to the devastating floods in QLD and in 2015 received a DVA Australia Day Award for her work in redefining DVA’s approach to service delivery.

She has qualifications in Public Administration and Policy, and Organisational Psychology.

Below are some of the wonderful team who work with Leanne and who make the Queensland division a standout compared to the other States. These girls really put in that afternoon, mixing with and looking after everybody, ensuring the food tables were always full of goodies and of course paying special attention to the prawns – everyone’s favourite.

|

||

|

||

|

Britnee Mitchell, Christina Bruce, Kerry Heath, Carol McDonald, Amanda Green.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Some of the people who were invited to the Christmas Party and listened to Craig and Leanne's welcome speeches.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Some of the others that were there include:

|

||

|

Chips Ross, Amanda Green, Terry Toon.

|

||

|

Chips and Terry are with the Atomic Ex-Servicemen’s Association. Chips is well into his 90's, is as fit as a fiddle and still has an eye for a pretty girl. Terry is the Editor of their wonderful little magazine, Atomic Fallout. The Association represents all those who served at Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Monte Bello, Emu Field and Maralinga and supporting bases around Australia.

The very capable Amanda is the Executive Assistant and gate keeper to the Deputy Commissioner, Leanne Cameron. She has been with the Department for a number of years and knows her job inside out. She is always available, willing to help, always sporting a big happy smile and some say the Queensland office wouldn’t be the same without her.

|

||

|

One day, while an old Australian ex-Navy bloke was chopping the branch off a tree high above a river, his axe fell into the river and sank immediately. When he cried out, the Lord appeared and asked, "Why are you crying?" The old Sailor replied that his axe had fallen into water and he needed the axe to supplement his meagre pension. The Lord went down into the water and reappeared with a golden axe. "Is this your axe?" the Lord asked. The old Sailor replied, "No." The Lord again went down again and came up with a silver axe. "Is this your Axe?" the Lord asked. Again, the old Matelot replied, "No." The Lord went down again and came up with an iron axe. "Is this your Axe?" the Lord asked. the old Sailor replied, "Yes." The Lord was pleased with the old Matelot's honesty and gave him all three axes to keep and the old Sailor went home very happy.

Sometime later that same old Sailor was walking with his woman along the river bank and his woman fell into the river. When he cried out, the Lord again appeared and asked him, "Why are you crying?" "Oh Lord, my woman has fallen into the water!" The Lord went down into the water and came up with ANGELINA JOLIE. "Is this your woman?" the Lord asked. "Yes," cried the old Sailor. The Lord was furious. "You lied! That is an untruth!" The old Sailor replied, "Oh, forgive me Lord. It is a misunderstanding. You see, if I had said 'no' to ANGELINA JOLIE, you would have come up with CAMERON DIAZ. Then if I said 'no' to her, you would have come up with my woman. Had I then said 'yes,' you would have given me all three. And Lord, I am an old man not able to take care of all three women in a way that they deserve, that's why I said yes to ANGELINA JOLIE."

And God was pleased.

The moral of this story is: Whenever an old Australian Sailor lies, it is for a good and honourable reason, and only for the benefit of others!

|

||

|

John “Sambo” Sambrooks (the people's champion), John “Prawn sampler extraordinaire” McDougal.

|

||

|

Greg Russell, Helen Bruce.

Greg is on the Committee of the Kedron Wavell RSL Sub-branch and is one of their senior Veterans’ Advocates. Helen has been with DVA in Brisbane for many years and is on the Executive Team which manages the Qld Office.

|

||

|

John “Griffo” Griffiths, Candice Carroll.

John is an EX-RAAF pilot, having flown most of its aircraft. He joined the Reserve after discharge from the PAF and was appointed as the Director of Performance Evaluation for the RAAF Cadet Scheme in Queensland before hanging up his head-set a few years ago. Candice is with the Veterans Care Association, which was set up to support returning veterans and their families to overcome Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other challenges when returning to civilian life. She is their Client Support Officer (Psychological Services).

|

||

|

Gary Stone AFP.

Gary is ex-Army and now the Veterans Care Association’s Padre and President.

|

||

|

Helen Bruce, Peter Schwarze.

Peter is ex-Army and did a time with the SAS. For some reason he delighted in leaping out of perfectly serviceable aircraft while in flight.

|

||

|

2 more (very important) hard workers. |

||

|

||

|

Lisa Baisden, Ben Isaacs.

Lisa and Ben were “Mine Hosts” and kept the liquid refreshments flowing well into the afternoon.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kel Ryan, Phil Lilliebridge, Brendan Cox, Ken Roma, Mal Rerden.

Kel is a Life Member of the RSL in Queensland and has also held elective office in a number of other ex-service organisations. Phil is on the Committee of the Kedron Wavell RSL Sub-Branch and is responsible for Projects and Defence Liaison. Brendan is the CEO of Legacy in Brisbane, Ken is the President of the Kedron Wavell RSL Sub-Branch and Mal is the President of Legacy in Brisbane and the Chairman of its Board of Directors.

|

||

|

Jenny Gregory, Lyn Wilkes, Judy Morris, Lisa Adams, Rosie Forster.

Jenny is the President of the State War Widows Guild in Qld, Lyn and Judy are ex WRAAFS, Lisa is from the Women Veteran’s Network Australia and Rosie is a past President of the WRAAF Association.

|

||

|

Wallaby Airlines Tie. (Some say it's worth millions??)

|

||

|

Leanne Cameron, John McDougall.

To thank Leanne and everyone at DVA Qld for the wonderful help they have provided for RTFV-35 Sqn (Wallaby Airlines) Association members in particular and all Vets in general, John McDougall, the President of the Association, presented Leanne with a Wallaby Airlines tie.

|

||

|

||

|

Amanda green, John McDougall.

Amanda green, who is always prepared to help whenever asked, was also presented with one of the Wallaby Airlines ties.

|

||

|

“The West Australian” - Thursday 6th Dec 2018

The pressure of a skills shortage looms over the WA resources industry. As the war for talent heats up, it will mean employers fighting over the same pool of potential recruits. This approach can only result in employers playing the wage game, not the skills game.

For business, there needs to be a transition to new and innovative ways to tap into potential talent pools to fill gaps. Resources sector executives need to consider how to strategically ensure the sustainability of their workforce, keeping cost efficient and also diversifying the abilities of their staff.

Recently I joined a panel with Senator Linda Reynolds, Mark Donaldson VC of Boeing Defence Australia and Linda O'Farrell, group head of people at Fortescue Metals Group, to discuss how a veteran workforce can provide a long-term and sustainable employment stream and improve business productivity. Around 5000 veterans leave the defence forces each year. They come highly trained, skilled and eager to start the next step in their careers.

Pleasingly, we all acknowledged the need to step away from the narrative that veterans are "broken" but rather recognise their qualities - the ability to operate in complex environments and a demonstrated and inherent understanding of safety and esprit de corps were cited as the strengths of veterans.

Ms O'Farrell (right) described to the audience of some of the biggest employers in the State, how veterans were contributing to positive outcomes for Fortescue. Since working with Ironside Recruitment to develop a veteran employment pathway for the rapid actual upskilling of heavy diesel mechanics, they have reported productivity gains across all workshops in which veterans are deployed. This speaks to the indomitable spirit of the Aussie soldier, sailor or airman and the ability of our serving men and women to face any challenge and turn them into opportunities.

Veterans spend 70 per cent of their Defence Force life training and learning skills which means employing them for attitude and training for skills cannot be a better strategy. Many veterans attain nationally recognised trade certificates including diesel mechanics, maintenance fitters, high-voltage electricians, marine fitters, riggers and plant operators. Specialists including unmanned aerial system operators can qualify quickly as automated haulage system operators and we're proving this already with some clients.

So, if you're not including veterans in your own strategic workforce plan, ask yourself why not.

|

||

|

Home cooking. Where many a delusional man thinks his wife is. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

|

hy flats aiming for the tea plantations behind the Task

Force airfield, mixing it with the choppers and Bird Dogs which normally

scuttled around at this level. As I did not hear anything back at the

squadron, I assume no one complained.

hy flats aiming for the tea plantations behind the Task

Force airfield, mixing it with the choppers and Bird Dogs which normally

scuttled around at this level. As I did not hear anything back at the

squadron, I assume no one complained.

s

skies, Wellington Airport's suburban control tower is due to wave on its

final flight.

s

skies, Wellington Airport's suburban control tower is due to wave on its

final flight.

f

the US Army Service of Supply (USASOS) South Pacific area occupied these

buildings from August 1943 to September 1944 after which the troops

moved up to Hollandia in PNG (west of Wewak).

f

the US Army Service of Supply (USASOS) South Pacific area occupied these

buildings from August 1943 to September 1944 after which the troops

moved up to Hollandia in PNG (west of Wewak). or is it because the throttles are very hard to push forward and need

two sets of hands to do it, or is it just because the pilot and co-pilot

are friendly?

or is it because the throttles are very hard to push forward and need

two sets of hands to do it, or is it just because the pilot and co-pilot

are friendly?