|

Vol 72 |

Page 10 |

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward

Contents.

Among the Quick and the Dead – East Timor, 1975

The following story appeared in Quadrant Magazine.

Volume 54 Issue 10 (Oct 2010)

When I first met Kerry Packer he was sprawled in his underwear across a bed in a motel in Darwin, a big seal in a singlet. It was at the end of August 1975. Civil war had erupted in East Timor on the 11th and Packer was determined to secure a deal my friend, Bill Bancroft, had been discussing with the captain of a fishing trawler regarding an unorthodox run to Dili. The price was $1000 a day, cash. Packer wanted a story. We wanted a lift.

Bill Bancroft was representing the Australian Society for Inter-Country Aid-Timor (ASIAT) which had been formed only weeks before by a small group that was ready to save the world after a successful project in Guam with refugees who had fled to that island after the fall of Vietnam. Michael Darby, the son of former Liberal, then Independent Member for Manly had organised the Guam project (of which I had been medical superintendent) and the three of us and a few others intended to send doctors and medical supplies to East Timor after Bill and I had visited that country in July and observed its medical destitution. For much of the country, the nineteenth century had not arrived.

On that trip we had received a welcome far beyond our potential by a desperate Portuguese government and many of the leaders of the local parties, the Timorese Democratic Union (UDT), the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN) and APODETI (the one seeking union with Indonesia) who had begun to struggle for power. The Portuguese had opened their hospitals to me, and their public health records, and had flown me to distant places in a little helicopter. We discussed an aid project and leaders of the government and all the parties assured us of their help and gratitude if we would return. The Bishop of Dili agreed to be on our committee.

We had collected about ten tea-chests of antibiotics and other medicines and had transferred them to Darwin before the civil war erupted, but with all the news of carnage and the retreat of the Portuguese doctors, we were determined to deliver the supplies ourselves. Bill, therefore, had gone to Darwin to try to find a way of getting there. After meeting the captain of the fishing boat, Bill telephoned Michael, who rang Channel Ten about the deal and then, after it showed no interest, Kerry Packer, who decided he would accept it and join his team of journalist Gerald Stone and cameraman Brian Peters.

Bill met me in Darwin and took me to meet the man. I had already met Stone and Peters on the plane to Darwin. Lounging on the bed, Packer demanded to know if the boat was his. I replied I had heard Channel Seven was interested and there was even talk of a combined media offer. His face reddened, his jaw protruded and a large foot propelled an aluminium case across the floor. “Well, there is $15,000 in that box. Let them get above that,” he declared. “And the banks are already closed.”

Carefully, Stone suggested the combined efforts of the others might, indeed, exceed that amount. Packer erupted, “Well, there is three and a half million dollars in Sydney. Let them get above that.” In reality, Packer’s sentences were much longer, generating clinical interest. As a paediatrician, I knew of Tourette’s syndrome with its tics, barking and grunting, and its compulsion for obscenities, but surely I was not observing it in a media magnate? He seemed too focused for the attention deficit of that disease and, in the classical form, the obscenities are usually broad and lessen with age. After the days of close companionship which followed, I settled for a new, hitherto unpublished, diagnosis of “effolalia”: the compulsive, repetitive use of the F-word as noun, adverb, verb, adjective, preposition and exclamation, with positive, negative, or no emotional affect but associated, overall, with disagreeable behaviour.

To complete the definition, I sought to quantify the use of the F-word and eventually settled on a conservative minimum of one word in three. Tourette’s is a congenital disease transmitted in dominant form. Noting a similar but lesser affliction in other journalists I wondered if they were inbred, or was the disease not congenital but infective? Or were Stalin’s geneticists correct: did a dominant environment determine phenotype?

In any case, Packer’s cash triumphed and the deal was clinched on the phone. Then there was a knock on the door. We opened it suspiciously to find a young journalist from another channel wanting to know if this was the room where the media were to meet to discuss a combined venture? I braced but Packer confirmed sweetly that it was indeed the right room but, regrettably, the wrong time. The meeting had been delayed until eight o’clock the following morning, when the young man should return and not be late.

Within half an hour, the room was empty and we were loading supplies onto the Kon Piri Maru. The crew apologised for the cramped confines in this former fishing trawler, blaming the former Japanese ownership which, they added, had been relinquished when the boat had been abandoned on a coral reef. Given this precedent of dubious proclamation, we all cheerily declared to Customs and Immigration that we were going fishing, though our piles of labelled medical and television equipment might have suggested otherwise. When Packer’s ex-Portuguese paratrooper bodyguard, Manuel, arrived, complete with arsenal, it could have been concluded we were off to start World War Three.

We set off in late afternoon and wallowed at nine knots all night and

the next day, with Packer increasingly worried his rivals would beat us

to Dili. Perhaps they would hitch a ride on one of the destroyers that

had been moored next to us at the docks. Distractions were few but,

perhaps in anticipation of an unfriendly reception or the need to dispel

rivals, Packer decided to check his weapons. Manuel appeared on deck

with a selection and I was dispatched to throw beer cans from the bow. I was happy to

comply because I thought we might all have a go. I hurled the cans onto

the passing waves but they bobbed cheekily to the rear. There were

problems with weapons jamming, surpassed by problems with accuracy as

spouts of water erupted far from the cans. Frustration was mounting on

the deck and I began to understand why Packer had only talked about

shooting elephants. Then one of the Territorian crew came to me with an

old .303 and wondered if I would give him a can. “Sure, I’ll throw it

for you,” I said. “No, I want to cut it up,” he replied, “I need to make

some sights,” whereupon he produced a pair of snips, fashioned a V from

a piece of the tin, screwed it onto the back of the barrel and took aim.

It looked ridiculous compared with Packer’s machinery and I felt his

scoffing regard justified until my next can leapt from the water,

twirled and disappeared. I was astonished. Packer retired below decks

with Manuel and his weapons. As the day lengthened, Packer’s visits to

the bridge increased in frequency: “Are we there yet?” His anxieties

reduced his memory of the bar that fixed the ladder to the

superstructure and which was high enough to miss a Japanese forehead.

Bill nudged me. “Watch this,” he said, “he does it every time.” Sure

enough, even in the wind at the bow we heard a fleshy thud and ongoing

remarks.

and I was dispatched to throw beer cans from the bow. I was happy to

comply because I thought we might all have a go. I hurled the cans onto

the passing waves but they bobbed cheekily to the rear. There were

problems with weapons jamming, surpassed by problems with accuracy as

spouts of water erupted far from the cans. Frustration was mounting on

the deck and I began to understand why Packer had only talked about

shooting elephants. Then one of the Territorian crew came to me with an

old .303 and wondered if I would give him a can. “Sure, I’ll throw it

for you,” I said. “No, I want to cut it up,” he replied, “I need to make

some sights,” whereupon he produced a pair of snips, fashioned a V from

a piece of the tin, screwed it onto the back of the barrel and took aim.

It looked ridiculous compared with Packer’s machinery and I felt his

scoffing regard justified until my next can leapt from the water,

twirled and disappeared. I was astonished. Packer retired below decks

with Manuel and his weapons. As the day lengthened, Packer’s visits to

the bridge increased in frequency: “Are we there yet?” His anxieties

reduced his memory of the bar that fixed the ladder to the

superstructure and which was high enough to miss a Japanese forehead.

Bill nudged me. “Watch this,” he said, “he does it every time.” Sure

enough, even in the wind at the bow we heard a fleshy thud and ongoing

remarks.

In the late hours of that dark night, we were off Dili when, suddenly, lights flashed from a nearby and unseen ship which turned out to be an Indonesian destroyer. The Territorians were amused by this and we continued in the same direction. We were then illuminated by a searchlight. The Territorians were delighted. Packer demanded retreat. The boys, however, would have none of that.

We concluded that the flashes were Morse code, and Packer demanded to know their meaning. The captain remembered he had a chart somewhere, which he eventually produced and began the interpretation. He asked Packer if he thought the signals were a dash, dot, dash and so on and Packer peered into the gloom. “It could be,” Packer concluded. “I’ve worked it out then,” proclaimed the captain. “It says if you come any closer we will blow you out of the water.” The crew found this exceedingly funny but I was with Packer, thinking they had gone mad.

You know you live in Darwin when.....

You discover you get sunburnt through your windscreen

The reeking hospital.

At dawn, all humour had disappeared as we edged into Dili harbour with the grey destroyer at our back and rings of fires around the city at our front. Shooting could be heard, and we remembered the stories of carnage. Would someone fire on us? How could we tell them we had medical supplies and a doctor? I had no idea the Red Cross owned that symbol and it had seemed a very sensible thing to sew red rag onto a white mattress cover with the help of fishing line and a straightened hook. I ran it up on the bow unaware of the criticism that would follow its unauthorised use and its alleged camouflage for the media, but it worked. Frank Favaro, who owned the Hotel Dili, saw the flag and come out in an outboard to meet us. “Have you got a surgeon on board? The hospital is full and there are amputations and things to be done up there.”

He was not exaggerating. When we got there we saw row on row of casualties: sixty-four people with serious wounds, on first count. One died within minutes of our arrival. The Portuguese had withdrawn days before, abandoning the wounded to slow and painful death. Some wounded lay still and silent to lessen the pain from shattered bones. Some were groaning and rolling around. Some were breathing with difficulty. They had little hope for survival and lay in pus, blood and excreta which exuded to the floor around their beds. Flies abounded.

The non-surgical wards were filled with patients suffering from heart failures, cancers, tuberculosis and other diseases and there were three children with paraplegia. The hospital stank. It reeked with despair. The only good news was that no one was about to give birth. I did not know where or how to start. I was not the surgeon Favaro had hoped for, I was a paediatrician but had worked in Africa in a remote mission hospital for a year and had picked up a few tricks. Would they be sufficient? And how could I perform them by myself? Where was the operating theatre and what anaesthetics were available?

I went to find out and was introduced to a phenomenon which had begun to take place around me. Staff had heard a doctor had arrived and were returning to work. The theatre was being prepared. The nurse anaesthetist was checking the equipment. I went back to the ward to select the first patient and found cleaners had begun to attack the mess. The transformation in the following hours was astounding—but what if they knew how little I knew!

My first patient was Joao Soriano, a young artist who had been shot in the abdomen and was developing peritonitis. He survived and presented me with one of his paintings before I left. I treasure it. My next was an obese Chinese woman with a gangrenous leg from a bullet which had shattered her femur. I amputated the leg with difficulty because it was heavy and the nurse stumbled as it came loose but bore it reverentially to a bin into which he dropped it with a thud. There were no complications with the amputation but what were those tiny wounds on her abdominal wall? Could they have been pellets of some kind? Her abdomen had appeared normal before the operation but I wondered how deeply they had penetrated. I explored them but could find no evidence of tracking into her bowel. She died, however, of shock several days later; I still worry that I was wrong.

Then a man arrived with a strangulated hernia, at risk from gangrene of the bowel. I had never done that operation before and was only slightly relieved to find an elementary textbook in the surgeon’s office. When my Timorese nurse handed me the scalpel I thought, “If only you knew.” He survived.

It was now late at night. I had run out of clean instruments and energy, but there were over sixty patients to go. I knew those on the end of the list would die before they chanced my surgery and so, next morning, I went with Favaro to the airport to start the engine of his plane in order to power up its radio and plead to Darwin for more doctors. The terminal and hangars were damaged, and so was his plane, but we were able to wheel it out and make our call though firing continued between Fretilin soldiers on the tower and UDT supporters in the bush.

Returning, I observed the burned houses, looted shops and rotting bodies

in that part of the town. We had to swerve around an unexploded mortar

bomb protruding from the roadway and then passed through an exchange of

fire from one side of the road to the other. We could feel shock waves from the bullets but it never crossed my mind I would be struck. I had

succumbed to the Balibo Syndrome of Australian invincibility which, I

believe, was to lead to the death of the journalists in October.

from the bullets but it never crossed my mind I would be struck. I had

succumbed to the Balibo Syndrome of Australian invincibility which, I

believe, was to lead to the death of the journalists in October.

My first patient that day was a small boy with a gangrenous leg. The bullet had smashed his femur in his groin near the femoral artery and his whole leg was black. He was very sick and I had delayed the operation until we had been able to transfuse him. I was very worried, as well as hot under my plastic gown in the tropical heat with only the open window for relief. I streamed perspiration, and grieved for that little leg, but he survived. Bless him.

Late that night, I found an upset Bill. Packer had sailed to Atauro, the island off Dili, to return to Australia with film from his venture. He had found leaders of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), including its regional director, M. Pasquier, stranded on Atauro in increasing frustration at their inability to cross to Dili, and had commissioned the Kon Piri Maru to deliver them. On arrival, it appeared to Bill that Pasquier’s preoccupation was protestation against the “misuse” of his symbol, a theme he quickly resumed with me when we were introduced. I was too tired to take him seriously but, next day, he made official, international complaints leading to criticisms of Packer in Parliament and by the Australian Journalists Association. I doubt they disturbed Packer. I also doubt Pasquier ever wondered how long he would have sat on the island without Packer’s help, or more profoundly, how long the wounded would have had to wait without Packer’s initiative. Anyway, it was me, not Packer, who made and flew the flag.

Bill and I returned to the hospital but it was not a peaceful place. Many patients were in pain despite our efforts. At 4.00 a.m. we were sitting on the stone wall which surrounded the hospital, overlooking Dili. We could see lights on the destroyer and some freighters that had arrived and, with tracers traversing the town and the noise of shooting and explosions, we concluded the Indonesians were coming. We had heard Radio Kupang had been threatening foreign “supporters” of Fretilin and we wondered what we should do when the Indonesians arrived. We concluded we had better stay in the hospital and headed to the store-room to sleep on the floor.

I had welcomed the Red Cross delegation, especially because two were doctors. The next day, I showed them the hospital and we visited the prisons. One was a surgeon, and we prepared to work. He had chosen as his first case a girl who had been shot in both elbows, and we were preparing to take her to theatre when a truck arrived with a soldier who had been wounded in the head. He was critically ill and we swapped patients, anaesthetising him for surgery on his bleeding brain.

I was relieved to be the assistant but, literally, when the surgeon was

poised to make an incision a message came that a plane had arrived for

the Red Cross team and he was to leave immediately for Australia. He

disrobed, wished me luck and disappeared. The assistants asked if I was

going to take over, or should they wake the patient up? But he was

deteriorating: one pupil had dilated and the other looked very big. I

took the scalpel and incised where the surgeon had intended and then

opened the bone, looking for the haemorrhage, but there was none at that

site. Another opening was needed, and then the blood began to flow:

first from the clot that was compressing his brain, and then from a

myriad of surrounding vessels. The clot was evacuated easily but the

little vessels would not stop bleeding despite clamp after clamp and

knot after knot with fingers that had begun to ache and then tremble on

the slippery thread. It was so hot, I could not see for perspiration and

an assistant was assigned to my eyes with a towel.

clot was evacuated easily but the

little vessels would not stop bleeding despite clamp after clamp and

knot after knot with fingers that had begun to ache and then tremble on

the slippery thread. It was so hot, I could not see for perspiration and

an assistant was assigned to my eyes with a towel.

Time passed in which I, the patient and the staff all began to sink. Suddenly, the door of the operating theatre was thrown open and two grinning, bearded faces declared in welcome: “G’day John.” I stared at them uncomprehendingly and then recognised two of my doctor friends from Sydney, Roger Gouche and Philip Chalmers (right), who had arrived in a plane organised by Michael Darby, despite a maze of bureaucratic obstruction, and funded by St Vincent de Paul. With the arrival of such cavalry, the tide of battle changed and the bleeding surrendered.

You develop a fear of metal door handles.

An unusual day.

The next day, with Roger taking over the surgery and Phil looking after the medical wards, I went for a drive around Dili in a Datsun utility Bill had acquired for our use and not so innocently adorned with our Red Cross flag. I did not think about it when he insisted I drove. I was marvelling at his “requisition” of the police headquarters for the official residence of our organisation, along with its kitchen and stores. We had heard two more doctors of ours might be arriving by plane and we headed for the airport. Bill was now widely known and was able to befriend the soldiers manning the tower and even borrow one of their rifles for a shooting competition with me. The Fretilin soldiers became interested to see if the foreigners could hit the bottles he had stood on the tarmac. I suppose they had become bored since fighting had stopped in that area. We, of course, were young and stupid. I scared the bottles with a few shots and handed the weapon to Bill. He turned it on automatic and fired from the hip. Bullets went everywhere and we all thought it was very funny. I thought he was putting on an act. I did not learn for a long time that the poor fellow was nearly blind with diabetes and crippled with renal failure. It explained a lot of things, why he would not drive, and his perpetual use of dark glasses, which had encouraged many to imagine he worked for a bevy of intelligence organisations.

When I learned of his disease, I realised, in retrospect, the immensity of his courage. I never once heard him complain, and he put himself in many situations in which his disease could have killed him. A few years later, in Australia, it did. The soldiers were ribbing us about missing the bottles, and everyone was laughing until we heard some zinging above our heads: then more, and lower. Good heavens, people were shooting back! Our soldiers demanded the return of their rifle and threw themselves down. In mutual affliction of the Balibo Syndrome, Bill and I remained erect, perceiving a funny side to all this, and an even funnier one when an RAAF plane arrived and taxied towards the tower. Out clambered the passengers. We wondered how long it would take them to notice the bullets. Not long, it proved, and they ran in file, ducking and weaving towards the presumed safety of the glass-walled terminal. How comical it appeared.

We noticed our doctors amongst the passengers and beckoned them to come with us in our utility. They jumped in the back and we took off for the gates but were just rounding a hangar when a projectile hit it with a great noise. I slammed on the brakes, and we all headed for protection behind a nearby bulldozer.

Three of us reached it. The fourth, however, caught his toe on the edge of the utility as he was leaping from the tray. His body extended and then arced to the concrete. “He is dead,” we concluded, immobile in our safety. But movement appeared in the fingers of an outstretched arm and a head rose from the tarmac. It apologised for the performance while, absent-mindedly, the fingers tried to reach some coins that had rolled out from a shirt pocket. The farce was not over. The firing had stopped so we decided I should drive to the road outside the airport which seemed separated from us by only a few bushes. I did so, but more shots propelled my friends blindly into the bushes where barbed wire awaited, suspending the rout on its spikes. I watched them fight the wire and then heard jumping on the back. Someone banged on the roof so I took off, spinning the wheels in the dirt. Further banging seemed to indicate the need for more speed. I obliged but, a few hundred yards down the road, spied the image of a friend in the rear-vision mirror, chasing us in the dust.

We continued for about a mile and came to a roadblock in time to see Fretilin soldiers firing a bazooka at a building where a UDT sniper was supposedly hiding. There was an argument about how the thing would work, then grimacing for recoil, then a roar as the trigger was pressed, followed by decremental sound as the missile careered past the building into the suburbs.

That evening, Bill convinced some cooks he had recruited that a special dinner of welcome should be prepared for the harassed new members of our team. Furthermore, he had borrowed a platoon of soldiers from Fretilin to ensure there would be no surprise attacks on our new headquarters. With all these preparations, the dinner started well with commandeered refreshments and, as I recall, curried prawns and all kinds of delights. We were pleased with life and recounted events with laughter until an explosion on the other side of the house. We had been dining in style in the garden but upturned the table and the prawns and stumbled over each other for the safety of the building where we crouched in darkness awaiting our fate. There was a gun shot in an adjoining room. We held our breaths. Then there was laughter from the room: women’s laughter. We began to smell a rat and sent Bill to check on the discipline of his troops. He opened the door of their room to find their number had grown to about fifteen and, strangely, all appeared to be asleep. As he stared, there was not a sound, until he heard a female giggle. To a man and entertaining woman, Bill’s troops were drunk. The grenade had been thrown for fun. The shot was accidental.

That night as we were trying to go to sleep, the doctor I had left in the dust at the airport, a good friend of mine, John Taylor from the west of Sydney, expressed alarm that his pulse was still racing.

You realise asphalt has a liquid state.

Saying goodbye.

In the morning we returned to the hospital to work on the backlog of

injuries and tend the new arrivals. Our increased numbers allowed us to

start a clinic in the town and begin to visit some regional centres.

John Taylor and I travelled inland to Aileu and Maubisse where we found

the usual destitution. We also found some UDT prisoners tied together by ropes,

shuffling along the road, and then a group of Portuguese soldiers who

had been left behind in their government’s rush. They were miserable but

physically healthy and we took a list of their names for the ICRC.

destitution. We also found some UDT prisoners tied together by ropes,

shuffling along the road, and then a group of Portuguese soldiers who

had been left behind in their government’s rush. They were miserable but

physically healthy and we took a list of their names for the ICRC.

The excitement of the day came when a young Fretilin soldier allowed the suspended log which had functioned as a roadblock to crash down on the bonnet of our car. The worry had been the boy soldiers manning the blocks with bows and arrows pulled back with quivering strings. The steel at the tip seemed worse than the barrel of a gun. More Red Cross doctors had arrived and it seemed wise for some of ours to join that organisation and concentrate on the hospital. Michael Darby had arrived and he, Bill, our remaining doctors and I sat down to ponder the future of ASIAT. We could see the need for medical clinics in Dili and such places as Maubisse, especially for mothers and children, and also the need for engineers and other tradesmen to help repair the destruction, and for school teachers.

We decided to return to Australia to seek personnel and funding to expand our work. I went to the hospital to say goodbye to the patients, especially the little boy, who was reported to be sitting up and eating. I was astonished, however, to be met on the steps by three members of the ICRC who declared it was now their hospital and I had no right to enter. For a short while I was lost for words, then I informed the officials I would walk right over them if they did not get out of my way. I am so glad they did. I was spoiling for a fight. The little boy was very friendly but did not know who I was.

While walking back barefoot to your car from any event, you do a tightrope act on the white lines in the car park.

The surrender of Baucau and the hijack of an RAAF plane.

See ALSO

We chartered Favaro’s plane to Baucau where we believed we could catch a lift back to Australia. When we landed, a young UDT civilian official ran to meet us to beg us to radio Darwin and organise evacuation for the remaining members of his party, who were convinced Fretilin was massing to attack what they believed to be a strongly defended town. He said their leader, Cesar Mouzinho, the former Mayor of Baucau and Vice-President of UDT, and others, had fled to the hills and there was hardly anyone left to fight. Mortars would fall on defenceless families.

An Indonesian destroyer had passed Baucau that morning and UDT families had crowded to the beach in the hope of rescue but the destroyer had refused to help them. Would we? As he pleaded, he was joined by a frantic Portuguese soldier who had defected to the UDT and who began to beg for his family with wild gesticulations of his rifle and sprays of saliva from his mouth. Grenades swung on his unbuttoned shirt, and when he concluded that Favaro might fly away, he declared he would shoot us all. More UDT soldiers arrived and another worry was revealed: the terminal was guarded by 100 or so armed “reservists” whose loyalty UDT had begun to question. They feared they might ingratiate themselves with the oncoming Fretilin by means of an expiatory massacre.

The soldiers were in mortal dread. I had seen that kind of fear earlier in the week in the faces of Chinese who had waded into deepening water in terror of Fretilin. They were rescued by lifeboats from the Indonesian destroyer after extensive searches on the beach of all the baggage they were carrying and the payment of “emigration tax” to Fretilin soldiers. Fretilin had declared its intention to destroy them and appropriate their bourgeois property when it was in power, and the Chinese had not forgotten.

Fretilin had renamed itself in line with the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary group in Mozambique and in 1975 the aftermath of victory by the adherents of that ideology was clear to those with eyes to see. I had also seen a mob of hundreds of East Timorese pressing in terror against the gates of the port in the hope of fleeing Fretilin on the Kon Piri Maru when the boat was about to return to Australia. Women and children had clung to me, and such was the panic I was certain some would be crushed to death. I had also seen that fear on the faces of some of the UDT prisoners in the Fretilin jails when we first arrived. I recognised previously proud men reduced to cowering victims. The group at the airport said they wanted at least to surrender peacefully and begged we would mediate on their behalf.

We wondered if we should set off to meet the oncoming Fretilin but decided, with Favaro (later acknowledged to be associated with the Australian intelligence services) that he should take off and radio Darwin to pass on the message of surrender to the Fretilin leadership in Dili. He would also request the ICRC to send a team for mediation. Favaro took off. We raised an Australian flag on the terminal, in the company of a white sheet, and then wondered what to do next. Michael Darby declared that, if they wanted to surrender, they should all lay down their arms. In the manner of a former military officer, he got them to line up and deposit their weapons in order on the tarmac. The reservists seemed glad to comply. They appeared to have had enough of this conflict.

Before we left Dili we had promised Fretilin we would check on the welfare of their prisoners in the UDT jails, so Bill and I headed into town, leaving Michael at the airport with his soldiers. At the prisons, we found the guards terrified and ready to shoot the restless prisoners who had heard victory was on their side. Inside, some of the prisoners were equally ready to kill the guards and any other members of the UDT they could get their hands on. Others yelled and danced in triumph. I noted their physical condition and found no one as abused as some of the UDT men in Dili. One of the Fretilin prisoners, Eduardo Santos, was being held in a separate room and we were able to converse quietly. He was well educated and fluent in English and shared my concern about things getting out of control. I persuaded the guards to release him and several other prominent Fretilin leaders in order to try to prevent disaster. These men addressed the prisoners and the guards and emotions seemed to settle. They said the prisoners should remain in jail until the surrender had been undertaken peacefully.

With the help of Santos we tried to telegraph the advancing Fretilin but

the wires were down. We returned to the airport, intending to continue

on the road to Dili with Santos and others in order to meet the oncoming

Fretilin force. At the airport, however, we were amazed to see an RAAF

transport plane parked on the tarmac. Favaro’s message had been received but the

plane was, reportedly, already on its way to Baucau because the ICRC

wanted to check on the welfare of one of its doctors who had remained in

the hotel. To the UDT soldiers and their families gathering around the

airport, the plane was a chariot from heaven and though eyes did not

leave the tree line for long and ears remained primed for explosions,

there was conviction of salvation. I don’t believe the ICRC ever

understood the fear that preceded their arrival. I later learned more of

that fear when I was privileged to read some of the letters Cesar

Mouzinho had sent to his wife from prison in Dili.

plane parked on the tarmac. Favaro’s message had been received but the

plane was, reportedly, already on its way to Baucau because the ICRC

wanted to check on the welfare of one of its doctors who had remained in

the hotel. To the UDT soldiers and their families gathering around the

airport, the plane was a chariot from heaven and though eyes did not

leave the tree line for long and ears remained primed for explosions,

there was conviction of salvation. I don’t believe the ICRC ever

understood the fear that preceded their arrival. I later learned more of

that fear when I was privileged to read some of the letters Cesar

Mouzinho had sent to his wife from prison in Dili.

He explained how UDT had advanced from Baucau to the eastern edge of Dili but was then forced to retreat, suffering many wounded. At one place a truckload of UDT soldiers was ambushed. When it halted under the fire, grenades were thrown among the men in the back. Mouzinho was appalled that they were not given the chance to surrender, asking, “What sort of men are we fighting?” The arrival of the wounded with these and other stories was basic to the fear in Baucau.

When I arrived at the airport, a conference was taking place between UDT officials and the leader of the ICRC, Andre Pasquier. Presuming I had some authority and because I was known to some of them from my earlier visit to Timor, the officials asked me to join the meeting where they were trying to convince M. Pasquier of their desire to surrender. But the Swiss gentleman was not a pushover for such delicate matters and insisted on protocol. To begin, he announced the group must have an elected leader. But they had none and I knew they were reluctant to announce that their real leaders had taken to the hills. They sat dumbly, looking at each other helplessly. Pasquier also assumed I had some authority and asked me to explain the matter with greater clarity to what he presumed were “my men”. I tried, but with no success. An uncomfortable silence followed in which eyes darted from the tree line to the weapons. Pasquier broke the silence. He put down his pen, sat back in his chair, and announced, “Then there will be no surrender. It is not legal if you have no leader.”

He asked me to speak to the group in private and we retired to the parapet which overlooked the airport, the families, the plane, and the weapons which were under the nominal control of Michael and Bill. I said they must elect someone for appearance’s sake but the day was lengthening and fear was eroding rational thought. They said they would nominate a leader and were “prepared” to surrender but raised the stakes by declaring that those in danger of reprisals from Fretilin must be evacuated in the plane. Then they decided their families must be allowed to accompany them. If they were denied, they would take back their weapons. Some began to mutter about shooting the plane if it tried to leave. Now that he had his leader, Pasquier was prepared to accept the surrender but steered the request for evacuation to the Squadron Leader.

I was nominated to relay the request and hurried down the stairs to the Squadron Leader, for I, too, had become paranoid about mortars, women and children. The Squadron Leader was as forceful as he was blunt. There would be no such thing as evacuation. I returned to the group on the parapet with what we all believed was their death warrant. Pandemonium ensued. They argued and shouted and ran down the stairs towards the weapons. Some were saying they would destroy the plane. As they spilled onto the tarmac they infected their families with panic. I began to look for somewhere to hide when the shooting began. The small group of Fretilin leaders I had brought for calming purposes now stood alone, silent, confused and frightened. Their sincere suggestion that the security of the UDT soldiers could be guaranteed by their being locked up in jail was not helpful.

Then, in the midst of the chaos, three nuns turned up with a frantic priest begging for their evacuation. He invoked the atrocities such women had suffered in Africa, where I had worked not long before, and I needed no persuasion to ask the Squadron Leader for mercy. He demanded to know, “Who are you to request me for anything?” I began peaceably by declaring, “I am an Australian citizen and I am formally requesting” their evacuation but soon found myself vowing, after his refusals, and I suspect at the top of my voice, that if he abandoned them and anything happened to them, I would spend the rest of my life in his pursuit. I think my nerves had got the better of me. The Squadron Leader radioed Australia and came back to report the plane was about to leave, but only the nuns would accompany it. This news spread to the crowd lined up behind the weapons, near the open back of the plane, and was not well received.

Suddenly, the Portuguese soldier who had sprayed saliva earlier in the day broke ranks, strode to the weapons, selected some grenades, an automatic rifle and a pistol, and walked calmly before the incredulous eyes of the Squadron Leader to the beckoning tail gate of the plane where he jumped up, squatted down and announced that he, his wife and their three children would be joining the flight. Pasquier tried to reason with him, citing all kinds of regulations, but the soldier changed his mind on only one detail: he broadened his invitation for the whole crowd to join him. There was a wild rush of children, bananas, bottles of drink, buns and transistors and other precious goods as the crowd surged into the heavenly chariot in joyous tumult. The chief charioteers had faces which seemed, however, to be glimpsing the other place.

RAAF officers tried to regain dignity by declaring the plane would not take off if weapons were not surrendered. Again I was invited to speak with “my man” the Portuguese. I did so and he happily gave up his grenades and the rifle but refused to part with the pistol until the raising of the tail gate and the coughing of the engines convinced him all was well. By this stage, Bill and Michael had cunningly joined the refugees in the bowels of the plane but, somehow, I remained outside, and suddenly wondered what was going to happen to me. The Squadron Leader appeared in a door above and threw the pistol towards me. It twisted in the air and I was sure it would go off when it clattered at my feet on the concrete. It did not. The door remained open. I was in.

There was much celebration by the refugees on the trip to Darwin, and laughter when the Portuguese soldier explained he had no alternative but to stay squatting on the tail gate because he had torn away the seat of his pants and had no underwear. Now in a colourful sarong he was the perfect host, distributing RAAF rations he had found in a big box. When we landed in Darwin we realised things were not normal. We passed by the terminal accompanied by a lot of vehicles with flashing lights. Michael, Bill and I tried to join the bus with the refugees, but we were recognised and taken in a special car to a special place. I was invited to enter a room and heard the door bang behind me, to find it had no handle. During the night there was much questioning and reports to be written but to our relief we were released before dawn. It appeared the authorities were keen to minimise publicity of the hijack and we suffered no further inconveniences.

I learned the ICRC and the RAAF blamed us for inciting the people to

riot, leading to panic and the invasion of the plane. I was also told

that Indonesian authorities blamed us for the surrender of Baucau to the

communists. Gough Whitlam was to say, “Darby, on behalf of Fretilin, had

accepted the surrender of Baucau on September 8.” What nonsense. More

irritating, personally, was Gough’s allied statement that “by the first

week in September ... Red Cross members were supplying the only medical

service in East Timor”. Mouzinhou’s letters add another perspective to

the surrender. They reveal his despair for the safety of Baucau and an

agonised sense of spiritual responsibility. He was a committed Catholic

opposed to communism, but had concluded that “to resist is too much

sacrifice”. Therefore, he sent a message to Australia on September 3

from the airport in Baucau, pleading for evacuation of civilians and UDT

leaders in a process of surrender. He says he chose not to be part of

that evacuation but to hide in a small mission in the hills in order to

be able to contribute to a later leadership, as he was convinced a

multinational peacekeeping force would, surely, intervene.

in September ... Red Cross members were supplying the only medical

service in East Timor”. Mouzinhou’s letters add another perspective to

the surrender. They reveal his despair for the safety of Baucau and an

agonised sense of spiritual responsibility. He was a committed Catholic

opposed to communism, but had concluded that “to resist is too much

sacrifice”. Therefore, he sent a message to Australia on September 3

from the airport in Baucau, pleading for evacuation of civilians and UDT

leaders in a process of surrender. He says he chose not to be part of

that evacuation but to hide in a small mission in the hills in order to

be able to contribute to a later leadership, as he was convinced a

multinational peacekeeping force would, surely, intervene.

Hearing of Fretilin’s victories, he decided his hiding might prolong bloodshed and he decided on September 6 to return to Baucau to try to effect a peaceful surrender of the city and the eastern part of the island. He duly surrendered to Eduardo Santos, was imprisoned, transported to Dili in the back of a truck with pigs, and displayed in villages along the way. Beatings followed, then his execution by Fretilin along with some sixty other UDT prisoners in November. After our release from custody in Darwin, we returned to Sydney and secured support to increase our team in Dili. We ran a clinic with a doctor and several experienced nurses, and we sent various tradesmen and a school teacher. We maintained cordial relations with Fretilin, many of whose leaders dropped in for a chat. I remained frightened by their ideology and was worried about their association with prominent communists in Australia.

Denis Freney, for example, was a central committee member of the Communist Party of Australia and leader of the vocal Campaign for an Independent East Timor, which functioned as a foreign affairs department for Fretilin. Others of our team were not convinced Fretilin was motivated by a dangerous ideology. In any case, we tried to be independent, though we were to learn the ICRC regarded us as “political”.

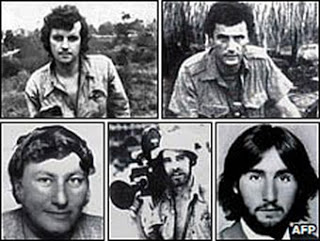

Returning with the Balibo victims In October, I returned to Dili in a chartered plane in the company of Brian Peters and Malcolm Rennie, who were shortly to die in Balibo. I had grown to like Peters on our earlier trip, but had never met the quieter Rennie. We parted on the day after our arrival. We had agreed to fly together to Oecusse, the Portuguese enclave in West Timor, to check on the medical conditions, but during the night they had received a better offer. The President of Fretilin, Xavier do Amaral, had organised to send them to the border where the Indonesians were believed to be assembling for attack. I bade them farewell as they took off in a jeep with Ramos Horta, wearing army uniforms. I did not think they ran any particular risk in that attire but felt they were being a bit “mug-lairish”’. Peters had several times expressed his regret that he had never reported from Vietnam and his last statement to me was that he was going to the border and was not going to return until he had “good footage”. Flying west over the area in which they were to be killed, we thought we would take some good photos of the Indonesian destroyer and various landing craft assembled off Batugade. We headed towards them, preparing our cameras, until it dawned on us we might get shot and we wheeled out to sea. The people of Oecusse were as poor and sick as everyone else in East Timor, but there had been no fighting and they were expecting to be integrated with Indonesia.

Sticking your head in the freezer and taking deep breaths is considered normal.

The mysterious Zantis

Another man who accompanied me to Dili on that trip and then to Oecusse was Jim Zantis, an associate of Michael Darby and Andronicus coffee. I had never met him before but became aware of a project for the exportation of coffee and other things for the financial benefit of, at least, Fretilin. John Izzard is mistaken about Zantis’s role with ASIAT. He was not “toing and froing” to Dili and had nothing to do with the “setting up” or running of our clinics. He visited our work on that trip and was reported to have a way with children. I agree he was a “shadowy” figure who may well have bragged about lots of things, including smuggling gems, but I knew no one who suspected him of working for ASIO.

The idea is preposterous but, on the other hand, rumours swirled in Dili and some were convinced my quiet friend Bill Bancroft worked at least for the CIA. I learned enough of the ambitions of Jim to decide there must be a parting of the ways. ASIAT was running a medical aid project in which accountability and transparency were essential. There was no place for an export business in conjunction with the de facto government. Un-associated with any ASIAT staff or intentions, a barge of coffee did leave for Darwin before the Indonesian invasion in December. The proceeds were locked in a bank and Izzard suggests a withdrawal form needed a second Fretilin signature to that of Ramos Horta, and that Zantis tried to return to Timor in 1976 to secure it. I know nothing of this, but suspect the bank was reluctant to part with the money because the ownership of the coffee was uncertain. Fretilin had no plantations other than those it had seized.

A cup full of ice is considered a great snack.

Saved by betrayal

On December 4, we were informed in Sydney by the Australian government that our workers should be evacuated from Dili. I interpreted this to mean an Indonesian invasion was imminent and sent a cable to our medical director, urging him and the nurses to leave. He never received it, which perhaps suggests that Fretilin wanted foreigners to stay. But, on December 5, an ICRC official in Dili insisted the team leave. It refused. He persisted, saying the team should, at least, go with the Red Cross to the island of Atauro, from where it could commute daily with the Red Cross to Dili. Our medical director was sceptical of this offer from the Red Cross, which had until then refused any co-operation with ASIAT, including transportation of medical supplies in otherwise empty planes. We had to charter a special plane to take vaccines to Timor, and the Red Cross would not even convey letters to our nurses. The director asked, “How much would the Red Cross charge?” “Nothing,” was the reply, “just leave your things and come.” So, expecting to return, the nurses left their belongings, including one nurse’s mementos of a recently deceased husband, and went to Atauro.

The next day, the team observed intense discussions between ICRC and

RAAF officers and noted that some Red Cross people were returning to

Australia. The team wanted to stay on Atauro but an ICRC official now

said they needed the permission of the Portuguese Governor of East

Timor, who had taken refuge on the island when the civil war had erupted

months earlier. They went to the Governor who told them they could stay

on the island if they had the permission of the ICRC. Its official then

“staggered” the nurses by declaring it would be in the Governor’s

interests “if such politically associated people were to leave”.

island if they had the permission of the ICRC. Its official then

“staggered” the nurses by declaring it would be in the Governor’s

interests “if such politically associated people were to leave”.

Having abandoned his responsibilities for Timor long ago, I suppose he had no inclination to oppose any suggestions from the Red Cross and, under the watchful eyes of otherwise inert Portuguese paratroopers, the team was “helped” onto a revving Hercules. The nurses were crying. There was an enormous feeling of grief and betrayal. But the Indonesians invaded Dili two days later and their lives had, surely, been preserved.

No-one cares if you walk around with no shoes on.

Quixotes to the rescue?

In January 1976, burdened by concern for the East Timorese, and deluded by the Balibo Syndrome of invincibility, Bill and I determined to return to the southern coast with medical supplies, another doctor (a real surgeon) and a radio operator (who was, in fact, an Ansett pilot, then on holidays but who had been responsible for transporting all our original supplies to Darwin). With the financial help of Community Aid Abroad and in the company of Gerald Stone and a new cameraman from Channel Nine we hired the barge Alanna Fay in Darwin. We presumed we could slip out to sea as before, land at Batano on the southern coast and make our way inland to Same where we could establish a hospital for the refugees we believed were heading south from Dili. We did not intend to stay there permanently, but to be an advance party for others to follow. We had prepared a statement for release to the involved governments and the media that we were “neutral” and going to help civilians.

The venture was a fiasco from beginning to end. A rival newsman could not be persuaded to delay reporting his discovery of our loading the barge and our intentions were broadcast nationally hours before we left. It began to rain, and the wind increased. The captain was late and boarded the flat-bottomed, flat-fronted barge with suspicious uncertainty. We launched ourselves into the worsening storm. I was in the wheelhouse a little later watching great sheets of water crashing from the front of the barge onto the windscreen on the upper deck, and we were not even out of the harbour.

At sea, the crew reckoned the waves must have been sixteen feet high, but who knows what to believe from Territorians? The captain by that stage was beyond communication. One of us had watched in astonishment as he turned the big steering wheel to the left and followed the rotation to the floor. A crewman who had come to his aid was asked if the captain suffered from heart disease, but he reassured us he had merely had a couple of drinks and would be all right after a little sleep. We were allotted the floor of the galley as our place to sleep and we tried to find comfort on the steel. I noticed Stone in a foetal position under a table which was fixed to the floor. I took a sleeping pill, then doubled the dose. We tried to close the door but it was rusted open. The wind howled, the waves crashed and it was hard to stay in one place on the floor.

In the middle of the night, dark water surged through the door, welling around my sleeping bag. It must have been a huge wave, as we were high above the level of the sea. And then I awoke and all was calm, no noise, no movement. I could not believe it and looked out the door to perceive in the darkness tall, mollusc-encrusted pillars rising from still waters. Where on earth were we? We were back in Darwin, moored at the pier at low tide. The engine had broken down in the rough seas and we had been forced to return. Customs and Immigration and other officials were abounding. In the lowest of spirits, we had to unload the barge in deep mud before a scathing audience.

I didn’t believe the story of the broken engine. I was convinced the captain had responded to orders from on high, however, when I met him years later he confirmed the breakage of some essential pipe. He changed my mind; but I was unable to change his conviction that we were running guns for Fretilin. Guns or not, we would have died in Timor, if we had not drowned trying to get off the barge. Batano, where we were headed, was bombed two days later and then invaded by the Indonesians. We would never have got the radio to work. It was in pieces, needed a complicated aerial, and despite his best intentions our Ansett pilot was not trained for that sort of thing.

As John Izzard has described it, the cat-and-mouse game of radio communications with East Timor had begun. The supplier of the radio had arrived in what was supposed to be great secrecy for our period of instruction in a hotel room. We had taken a “no worries” approach to the tangled mass of wiring and the black boxes with dials that been unwrapped from a brown paper parcel with conspiratorial zeal. Nor were we concerned when we learned the purveyor was a leader in the local branch of the Australian Communist Party. We never expected to meet any Indonesians, let alone to have to dissociate ourselves from our sources.

I gave up on Timor after that, though I was aware of Zantis’s efforts to make another run. After the Alanna Fay fiasco, it was put to me on ABC radio that we had been quixotic in our efforts to return and I tried to defend myself. It is hard to describe the motivations of those days. There was not the plethora of aid organisations that exist today and we felt a lonely responsibility. It could be said we were besotted by that burden. It should be said that some were motivated by Christianity, myself included, but, whereas that belief inflamed the sense of responsibility it did not contribute to the sense of invincibility. We did not seek martyrdom or believe we would be protected from it. We simply never thought it would happen. It was, I believe, the same combination of feelings of responsibility and invincibility that led the journalists to their deaths in Balibo, and we were fortunate none of our team suffered that fate. In trying to return to Batano, we were extravagantly impractical in our commitment to a romantic ideal.

East Timor had a way of turning people into Quixotes.

Dr John Whitehall is Professor of Paediatrics at Western Sydney University. His 50 year career began at Sydney University, continued through developing countries and western Sydney as a general paediatrician, then focussed on neonatology before coming to WSU. For 15 years he was Director of Neonatal Intensive Care in Townsville, North Queensland, which included ante-natal diagnosis, resuscitation, management and transportation of premature, dysmorphic and sick neonates, many of whom were Indigenous. In Townsville, he was deeply involved in the establishment of the medical school at James Cook University and, for 20 years, taught modules of Tropical Paediatrics in the Masters programme in the School of Public Health. In recent years, he has also worked as a consultant physician in PNG, Sri Lanka and Madagascar. Currently, he teaches, leads research and has duties in general paediatrics.

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward