|

|

||

|

||

|

Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Profit Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Links |

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

|

John Laming

Aeroplanes and other stuff. |

||

|

Contents:

It wouldn't happen these days. My friend George the Stuka pilot.

|

||

|

My Friend George, The Stuka Pilot.

In late 1952, the sole Royal Australian Air Force contribution to the defence of Darwin was two Wirraways, a Lincoln bomber and a Dakota. A few weeks before my first arrival at Darwin, one of the Lincoln pilots, Warrant Officer Jack Turnbull, a former Spitfire pilot, wrote off a Wirraway in a crosswind landing. The Wirraway was tricky to land in crosswinds and Jack had lost control and ground-looped seconds after touch down. He exited stage left quickly as it caught on fire.

The CO of the base, former Catalina pilot Wing Commander “Bull” McMahon, was none too happy at losing the Wirraway, effectively reducing Darwin’s airborne defence capability by half. The Dakota and Lincoln didn’t count because they had no guns.

Having recently flown Mustangs, I prevailed upon the Wing Commander to let me fly his remaining Wirraway, on what we termed continuation training. In reality, that meant buzzing herds of buffaloes in the plains to the east of Darwin and scarping at 50 feet above dozing crocodiles in Arnhem Land. To make the trip strictly legal, we would carry out a VHF DF (Direction Finding) instrument approach on returning to Darwin an hour later. In turn, this gave the RAAF air traffic controller practice at bringing aircraft into land in bad weather.

When not flying the Lincoln, I would persuade members of our crew to come with me in the Wirraway and teach them aerobatics. Naturally, we would finish the sortie beating up more buffalo and it was on one of these beat-ups I saw the leader of the herd turn and face us head on. While the rest of the buffs thundered away tails high when they saw the Wirraway coming at them low and fast, this big hairy bull buffalo just propped, head lowered and pawed the ground. He was a brave beast and I was glad that our engine didn’t pick that moment to stop because that bull buffalo would not have taken prisoners.

While based in Darwin I became friends with a Sergeant reservist pilot called George Petru. In 1948, George had escaped the communist regime that had taken over his native Czechoslovakia and, after many adventures, eventually arrived by ship in Darwin where he found a job as a surveyor with the Department of Works. Previously he had flown Junkers 87 (Stuka) dive bombers with the Czech Air Force.

Faced with marauding Russian troops, he stole a Messerschmitt ME109 fighter and fled his homeland chased by Russian fighters. The ME109 was a fast German designed single seater, which enabled him to outrun his pursuers. Perhaps more out of admiration of his exploits than pressing need, the RAAF accepted him as a reservist and George was given RAAF pilot wings despite never having been flight tested to service standards. He loved Australia and having read of the exploits of the RAAF fighter ace Bluey Truscott, was so impressed that he changed his name by deed poll from Petru to Truscott.

George came along on many Lincoln sorties but he was not allowed to land or take off. He had never flown a heavy bomber and understandably was pretty ropey on instrument flying. For that reason, we would only let him at the controls when the sun was shining. For all that, George was one of the most enthusiastic pilots I have ever flown with and he would willingly come along as a crew member on some of our long ten-hour SAR sorties.

While the captain was having a break snoozing down the back on the hard metal floor of the Lincoln, I would slip George into the co-pilot’s seat and let him fly, while I kept my eyes open for the missing light aeroplane or yacht or whatever we were looking for. I was never game to leave the cockpit to stretch my legs while George was flying because I knew that if we had a sudden engine failure (common on Lincolns in the tropics), George would be unable to handle the situation.

One day I rang George at work and asked him would he like to come with me in the Wirraway for low flying practice – meaning chasing hapless buffaloes. I saw my mate – the big bull buffalo as a hairy cloven-footed version of Jaws, in need of a bit of stirring up – from a safe height, of course.

George was delighted to get into a single-engine aircraft again – his last one being the Messerschmitt hijacked from the Czech Air Force. After kitting him out with a parachute and Mae West life jacket we took off in the Wirraway, heading east to find the herd. Sure enough we found the old bull buffalo and George took a few photos of him from the relative safety of the back seat of the Wirraway.

After that, we followed river tributaries towards the coast for more low flying along deserted beaches to the east of Darwin. This was more dangerous than chasing buffalo because it was here that huge salt water crocodiles lay in wait for unsuspecting wild pigs and dogs. Perish the thought of an engine failure here.

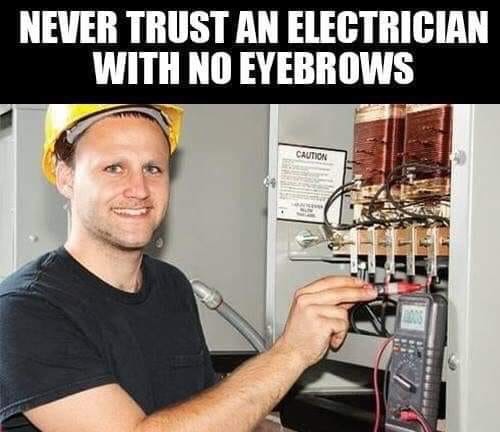

Our Lincoln crew with George far left.

George, of course, occupied the back seat of the Wirraway and was unable to see forward beyond my head in the front seat. For this reason, I decided it would be unwise to hand over control to him while low flying. This turned out to be one of my better decisions in life.

Having made rude gestures to the crocodiles and with plenty of fuel remaining, I climbed to 5000ft for some aerobatics. After completing a few barrel rolls and inadvertently spinning off a roll off the top, I handed over to George in the back seat, inviting him to try a loop.

Now you must remember that George had never flown a Wirraway before and therefore had no idea what a vicious beast it could be if roughly handled.

After a clearing turn, I talked George into the initial dive at 160

knots then told him to pull up and over into the loop. In the excitement

of the moment, I must have forgotten that George had flown the Stuka, an

aircraft specifically designed as a dive bomber. The typical dive angle

of a Stuka was sixty degrees and the drag from its huge wing dive brakes

kept the speed back to eighty knots. The stick-force needed to pull out

of the dive in a Stuka

George reefed about 4G at the bottom of the dive, causing the Wirraway to flick violently into a series of high speed vertical rolls and bouncing George’s head against the side window panels. I attempted to take control from the front seat to counteract the inevitable incipient spin. In the flurry of swear words from both cockpits, George had not understood my polite request for him to let go of the controls and kept hauling back, and so the Wirraway stuck it right up him and kept on flick rolling.

Eventually he let go of the stick and after recovering from the last known inverted position, I abandoned the sortie and we flew sedately back to base. Safely on the ground, George muttered ruefully that flying Stuka dive-bombers was a damn sight safer than aerobatics in a Wirraway and thanks very much for the offer but in future he would rather give Wirraways a miss and stick to flying Lincolns in sunny weather.

Some Lincoln crews were irritated by his fractured English and fanatical keenness to fly. As a result, he was often knocked back after turning up at the airport. When that happened, he would walk away sadly, knowing he was not wanted. Few knew that he was a brave man who had seen bloodshed and murder in his home country. It took great courage to steal a Messerschmitt and risk being shot down in a hail of cannon fire and I felt small in stature against this man.

For my part, I could rarely find it in my heart to knock him back when he turned up in his flying suit, cloth helmet, and a big smile. As I saw it, he was in the RAAF reserve and trying hard to do his bit for his new country. When the last of the Lincolns went to the wreckers in 1960, George had logged over 200 hours in the right hand seat.

From Darwin he moved with his family to Canberra. His English improved steadily and eventually he obtained his private pilot’s licence. A few years later, George made media headlines after getting lost near Oodnadatta in his Cessna 172 and forced landing on a clay pan. He was on his last legs when he was located, badly sun burnt, after surviving for one week by chewing his leather belt and shoe laces and eating toothpaste.

Back home his wife reminded him of his responsibilities as a husband and father and after recovering from his desert ordeal he took up gliding. The years passed until one day I saw a newspaper report that said a lone glider pilot had died in a crash near Canberra. Luck had finally run out for my old friend George, the Stuka pilot.

|

||

|

This is my step ladder. I never knew my real ladder. |

||

|

|

||

|

It wouldn’t happen these days.

Back in May 1995, AOPA (Australia) published a delightful flying story by Doctor Tony Fisher. It was called My Mustangs. During a recent culling of scrap books and other aviation paraphernalia from my shed, I re-discovered this lovely tale of derrring-do, and decided every pilot should read it; if only to show that once upon a time, when there were few regulations, flying was real fun. No ASIC cards, big brother surveillance cameras, anti-terrorist fences, or gun-toting grim faced Federal police at major airports.

While this story is set in 1963, many pilots now flying or “managing” fly-by-wire computer controlled Airbuses and Boeings weren’t even born when Tony Fisher first flew his Mustang. Tony’s story reminded me of another pilot I knew, who, 18 years earlier in 1945, found himself in a similar predicament. That pilot was Ensign Joe Ziskovsky of the United States Navy and his aeroplane wasn’t a Mustang but something infinitely more dangerous - the mighty Martin B-26 Marauder, known in those days as the Widow Maker. More of Joe and his Marauder, later.

In April 2009, AOPA still had Tony Fisher on its books and very soon I had his telephone number in Tasmania. To my relief, Tony had no objection to my relating his Mustang adventures and was quite happy to accept minor editing here and there. In his story, mention is made of Tocumwal aerodrome, NSW. After the war ended in 1945, Tocumwal became one of several storage units for surplus military aircraft. While most were destined to be melted down for scrap metal, others were stored in a flyable condition. I knew one RAAF pilot based at Tocumwal whose sole task was to regularly test fly each serviceable Mustang. I envied his job because believe me, there was over a hundred of them to be flown. Eventually after six months of this, he became so bored with flying a quick circuit in each Mustang that he began to hit the bottle. He was later posted to fly Lincolns at Townsville which is where I first met him.

In 1952, Tocumwal was a landing point for cross-country navigation flights by RAAF trainee pilots and their instructors from No 1 Basic Flying Training School at Uranquinty, NSW. We landed there for lunch one day and hardly had the propeller of our Wirraway stopped turning, when my instructor was off and away with a spanner and screwdriver to knock off the astro-dome of a B24 Liberator – one of a hundred or so parked in the sun. He had his heart set on a punch-bowl at home and the astro-dome was just the right size. The fact he was nearly bitten by a deadly red-back spider nesting in the fuselage of the B-24 didn’t faze him.

It was my first trip to this fabulous place with countless Mustangs, Mosquitos and Beaufighters parked on the grass with their once proud roundels fading in the hot sun. It was at Tocumwal where Tony Fisher bought his second Mustang for a song and had his first close shave. This then, is Tony’s story which he called:

|

||

|

My wife said I never listen to her, or something like that! |

||

|

My Mustangs.

My love affair with a P51 started in 1963 when I was approached by a non-ferrous metal dealer from Taren Point just south of Sydney. He knew I had a private pilot’s licence and asked if I was interested in buying an aeroplane he had obtained by tender to melt down for pots and pans. The name P51 didn’t mean a great deal at the time other than it was some sort of RAAF fighter.

My first aeroplane was a Fairchild Argus which I bought shortly after Sammy Dodd gave me my private pilot’s licence. I took my wife Helen to look at my pride and joy. She took one look and claimed, “you needn’t think I’m getting into that thing. That’s the old paper plane from Moree. My father went to Sydney once in that and said he could have got there quicker on a push bike”. That’s what you get for marrying a nurse from Moree.

When the non-ferrous dealer mentioned the P51’s 400mph cruise I thought of Helen’s father on a push bike. I was sold. The price having been agreed upon, $600, my next step was to find a way of getting it out of Sydney and down to Canarney, our 5000 acres at Jerilderie in NSW.

A mate of mine Chris Braun, who had flown P51’s in the RAAF, was now flying DC3’s for Butler Air Transport. I asked if he would fly the P51 down to Canarney. He was all in favour, but the Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) not only wanted a new 100 hourly but where was it going and what was to happen to the Mustang when it got there? It was decided it was to be part of a museum at Jerilderie. They fell for it.

While these negotiations were in progress, I located another aeroplane at Tocumwal, A68-193, an air reconnaissance Mustang for $700. Not saying a word to Helen, I bought that too.

It was now time for me to get a conversion as this was not possible at the time, due to prejudice against ex-service aircraft. I decided to obtain one while in the United States. My partner in Southern Cross Farms in Florida, Lane Ward, found a doctor in Merced, California, who owned a P51, and a US Colonel, who were prepared to lend me an aeroplane and teach me to fly it. There was a stipulation that prior to take off, I was to write a cheque for the full value of the aeroplane, because if I bent it – I owned it. When the Colonel found out I only had 200 hours and most of that in a Fairchild Argus and a G Bonanza, he thought it prudent that I obtained some time in a heavier aircraft such as a T6 Harvard.

Next day, the Colonel and I started circuits and landings in a T6. He was not all that impressed with my early attempts. “Say boy, watch that turn, don’t do that in the 51 or your wife is going to end up owning the aeroplane”. This went on for two days and by the end of it I was sorry I’d ever heard of a P51. Finally the hour arrived when I was due to fly the Mustang. “Now watch that right rudder, keep on top of it, don’t let the torque get away or you’ll knock that guy right out of the tower”.

He asked if the pedals were adjusted correctly. I could reach them but didn’t realize they moved a foot – not like the Argus only six inches. After last minute instructions re ram air etc, the Merlin roared to life and I taxied down toward the threshold.

“04 Papa ready,” I croaked. My voice sounded strange even to me. My throat was so dry. Finally it came. “04 Papa cleared for take off, make left turn, remain in the circuit area”.

I pushed the throttle forward 30, 40, 50, 60 inches Manifold Pressure. The noise of the Merlin was deafening. I could just make out the guy in the tower. Somehow I had a feeling he was just as frightened as I was. With the power came the torque and more and more rudder to keep the monster from racing off to the left towards the tower. I sank lower and lower into the cockpit. Lane later said I could have sworn to God there was no-one in the aeroplane as it took off.”

Airborne, I reached for the gear lever and retracted the wheels. The P51 was heading for the skies like the homesick angel it was. Two thousand feet per minute and indicating 200 knots. At 1,000ft I eased back on the throttle to 30 inches and noticing what looked like a 182 Cessna ahead, decided to follow it onto final. Suddenly the Cessna seemed to be attacking me backwards at 200 miles an hour. The landing wasn’t anything to brag about but everyone seemed pleased to see me and the aeroplane back in one piece. I reclaimed my cheque and we all went home to celebrate.

|

||

|

I want to grow my own food but I can't find any bacon seeds. |

||

|

|

||

|

No 2.

Max Annear and his mate Sid, two ex-RAAF Mustang mechanics, were checking out A68-193 for its ferry flight to Canarney homestead, Jerilderie. When they were satisfied it was ready, Max rang me and Joe Palmer and I flew down to Tocumwal in the red Ryan Trainer that I owned..

There was the Mustang sitting on the tarmac ticking over like a sewing machine. Max must have seen the anxiety on my face.

Tony Fisher’s Mustang at Jerilderie

“Tony, are you sure you can fly one of these things?” “You’ve got to be kidding” I said - trying to sound confident. “I was taught by the pride of the Yankee Air Force”. I failed to mention my total time on type was ten minutes.

It was drizzling with rain as I lined up and there was a sense of déjà vu. There was no tower and the pedals had been adjusted. The canopy clicked shut. I gave them a wave, lined up and opened the taps.

Hurtling down the strip I was about to ease back on the stick when there was a loud BANG, then another BANG BANG. The Colonel had said nothing about anything like this. I pulled off the power and applied full brakes. We were fast running out of strip. I left the runway and was now heading for the fence. “God, this is where I make Fisher’s gate. I hope the traffic on the highway gives me the right of way, to which surely I’m entitled.”

The Mustang stopped ten feet from the posts but the Rolls Royce engine was still purring. I taxied back to Max. “What’s wrong now?” I could hear the disdain in his voice. “I tell you Max, it made a loud bang. It seems to have stopped, - perhaps it was some carby ice”. He was not impressed. “I don’t know, but please check it out”.

I was glad to be back in the Ryan on the way back to Jerilderie. I wondered about what it would be like with some mad Jap in a Zero firing six cannons at you and the RR Merlin backfiring as well.

The Red Ryan

Several days later Chris Braun rang up and said he had permission to ferry Mustang A68-104 from Sydney down to Jerilderie. Fisher’s Airforce was beginning to take shape. About this time, Helen received a letter from my son Robby’s school inviting her up for a chat. We’re a little concerned about Rob. He has this wild imagination even for a five year old. He keeps saying his father owns two fighter aeroplanes, three seventy foot boats (names Vim, Derwent Hunter and Helsal), 500,000 acres in the Northern Territory and four cars including a Rolls and a Caddy”. I could never resist a bargain.

“But it’s all true,” poor Helen tried to explain. She was dismayed when she overheard the headmistress say “God, the whole family must be off. Imagine what the father must be like”. From then on I would cross the road anytime I had to pass the school.

It was Australia Day when we had the Carnarney Cup – a private, but everyone welcome air pageant. Max had found that one of the diaphragms in the Merlin had perished, but he had located a guy who had a new Merlin in his garage which he had bought at a disposal auction. He wanted ten dollars to change carburettors. Max also required an additional $80 for four drums of avgas (800 litres). Things were somewhat cheaper then.

That year we had 100 guests. Those we couldn’t put in the homestead were sleeping in the woolshed and under wings etc. There were 33 aeroplanes that year. Johnny Ault and I got up at 0500, jumped in the Ryan and flew down to Tocumwal where Max was waiting with Mustang 193 all fuelled and ready to go. I jumped in, taxied to the runway, switched to ram air, completed the cockpit check and opened the tap. Roaring down the runway I had a great view of where I nearly made Fisher’s Gate. Pulling back on the stick she soared sweetly into the air. Climbing to 3000 ft, I levelled off, set the revs at 2000 and the boost at about 30 inches and set the nose for Canarney.

About fifteen minutes later I could just make out the homestead on the Billabong River. The temptation was too great. I lowered the nose, increased the revs to 2500 and boost to 50 inches. The airspeed indicator began to climb well above 300 knots. At about 100 ft I levelled off and passed right over the homestead. Then pulling back on the stick I climbed away at 3000 fpm. Looking back, it was like treading on an ant’s nest. There were bodies coming out of everywhere, mostly in pyjamas and all wondering what all the noise was about.

|

||

|

As we end week 10 of the lockdown, I've been thinking about Osama Bin Laden. He was stuck in his house with three wives for five years, I'm beginning to wonder if he called in those Navy Seals himself. |

||

|

|

||

|

No 3. A short landing in a P51.

My uncle, Bob Macintosh, supervised both Canarney and a property called Concord, 3000 acres of the Cunnineuk Estate just north of Swan Hill. It took him six hours to commute between the properties. Although 25 years my senior, we were great mates and enjoyed one another’s company. He bred and loved race horses, but hated aeroplanes. I hated race horses, but after my mother’s death I had invested half of her estate into the two properties. When things were quiet on Canarney I would often jump into one of the Mustangs and within 20 minutes would be buzzing the Concord homestead. On one occasion there was a gentle breeze of about five knots coming from the west. There was no one home so I decided to return to Canarney via Cadell homestead which was Edgar Pickle’s place.

I flew over the homestead and could see Edgar on the verandah. There was no windsock, the airstrip was only 2000 ft long, and one way from the boundary to his front verandah, east to west. Taking a long final, I set myself up in the precautionary attitude and came in low over the boundary fence.

After a few seconds and almost half the strip gone, I realized I was doing a downwind landing. I was committed. I noticed that Edgar had vacated the verandah and was now behind a tree. “God,” I prayed. “here’s where I knock Pickle’s place right into the Wakool River”. Pulling back on the stick and left rudder I attempted to ground loop it to the left, but the brute headed straight for his house. In sheer desperation I applied full right rudder. Round she went in a great cloud of dust coming to rest not far from the fence and the entrance from the main road. A passing motorist seeing the dust and commotion drove straight in and up to the aeroplane, just as I was winding back the canopy.

“Are you all right, mate?” “Course I’m alright,” I claimed - not wishing to emphasise my predicament. “I thought you’d crashed”. “No way, that was a normal precautionary short landing”. "oh, yeah” he sounded a bit sceptical. What sort of aeroplane is that?” “A four bladed Ryan,” I lied. After all he could have been Arthur Doubleday’s (Director of Civil Aviation) brother. “How fast will it go?” “400 knots”. “What’s it worth?” “800 dollars”. “I’m learning to fly next year. I was going to buy a Cessna, but now I’ve seen one up close I think I’ll buy a Ryan”.

Pickles was still behind the tree and refused to enter into the conversation until after the prospective Ryan buyer had left. “Fisher, if you insist in arriving in this manner, I must respectfully request that you change your mode of transport”.

We inspected the aircraft taking particular notice of its undercarriage. Edgar gave it a clean bill of health so we retired for a well earned cup of tea.

The four bladed "Ryan".

The P51’s gave us a lot of enjoyment. They were at Canarney for about six years. One was sold to a fellow by the name of Don Busch and the other to a furniture salesman called Bob Eastgate. Busch unfortunately killed himself due I believe a C of G problem in a steep climbing turn. The other is occasionally flown in Victoria, but not, I’m told by its owner.

I have the greatest admiration for this aeroplane which is far more forgiving than many believe, however, my greatest admiration goes to the pilots who flew them in the medium for which they were designed – combat.

While at Jerilderie, the aircraft were kept in top mechanical condition by trained RAAF servicemen from Tocumwal. During these six years, we had no airframe or engine failure whatsoever, which speaks volumes for the aircraft reliability. They were housed in a specially constructed hangar, not a barn as has been claimed by the uninformed. They were flown by many pilots including Chris Braun, Joe Palmer, Bill Pike, John Lindner, Charlie Smith, Johnny Ault, Les Barnes and Edgar Pickles. We were all cavalier in many attitudes to life, but never to our aeroplanes.

Although that is the end of Tony Fisher’s story, I will add a postscript. Remember that Tony had only a private pilot’s licence and barely 200 hours when he first flew the Mustang. All he had flown previously was a Tiger Moth, Ryan Trainer and the Fairchild Argus. Certainly he had never had an instrument rating. Most RAAF fighter pilots of that era also had around 200 hours before flying Mustangs – but most of those hours were on Wirraways and their training included instrument flying. It places Tony’s experience of flying the Mustang in perspective.

The various other pilots that were involved with Tony Fisher’s Mustangs were either serving or former RAAF or airline pilots. One who was not mentioned was Bruce Clarke – a C130 Hercules pilot. I flew with Bruce on HS 748’s of the RAAF VIP squadron at Canberra. He was able to cadge a flight in one of Tony’s Mustangs after helping to arrange for mechanics to transport glycol coolant from the RAAF base at Richmond NSW for the Merlin engines.

At the time the Mustang he flew had a canopy problem so Bruce flew it without the canopy. It was very noisy, he said – and showed me a tiny photo of him taking off at Jerilderie, sans canopy. Several of the characters in the story have long since passed on – after all it was 46 years ago. Tony Fisher added more to his story when I talked to him last week. Around 1965, a couple of RAAF pilots heard about his Mustang and after driving to Jerilderie asked Tony for permission to fly it. He led them to where one Mustang was under cover in a sheep shed. The Mustang was covered in dust and bird droppings and both pilots thought better of the idea. Tony wheeled the aircraft out of the shed, started the engine and after take off did a few aerobatics. The pilots were amazed and changed their minds and each flew the Mustang for a circuit. As I said earlier, those sort of things happened in those days – but today – no way.

In 1970, Mustang 193 that Tony picked up from Tocumwal, had a sad ending when it crashed at Bendigo Victoria, killing the pilot, Don Busch. The second of Tony ‘s Mustangs - former A68-104, was still flying in 2008 at Point Cook in Victoria. Later that year it was damaged in a belly-landing after one wheel would not extend.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Joe Ziskovsky and his B-26 Marauder.

The Martin Marauder was a medium bomber used by the United States Air Force in World War 2. One pilot who flew the Marauder, Lt. Col Douglas Conley, in a book published in 1975 entitled “Flying Combat Aircraft” by R. Higham and A. Siddall, had this to say:

“The aircraft had a performance average of one crash a day from unknown causes and with all hands killed is reason enough to make anyone jumpy. Conley admitted to considerable apprehension on each take off. “The stubby wings were responsible for the Marauder’s nickname in the USAF of The Flying Prostitute, she had no (or very little) visible means of support. The serious control problems upon engine failure earned her the name the Martin Murderer and the reputation of a Marauder a day in Tampa Bay was assigned to her about the time I began flying her in the fall of 1942”.

In 1977 I flew an F28 of Air Nauru from Nauru Island to Majuro airport in the Marshall Islands of Micronesia. Among passengers waiting there was Captain Joe Ziskovsky, a former wartime Catalina pilot who after having worked for the Boeing Aircraft Company in Seattle, was joining Air Nauru to fly the Boeing 737. After retiring from Air Nauru a few years later, he moved to South Africa to be with his wife who was a school teacher. There he flew various light aircraft on safari charters. One of his letters to me explained how he became a pilot in the United States Navy in 1943. During the early part of the Pacific war against the Japanese he was an Ordnance man in the US Navy whose job was to service bomb sights and guns of US Marine aircraft in the South Pacific. During the bitter fighting between American and Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands in 1942, Joe served at Guadacanal, surviving daily shelling by Japanese ships aiming at Henderson Field, recently captured from the Japanese army.

He re-mustered as a pilot and flew Catalina flying boats until the surrender of Japan in 1945.

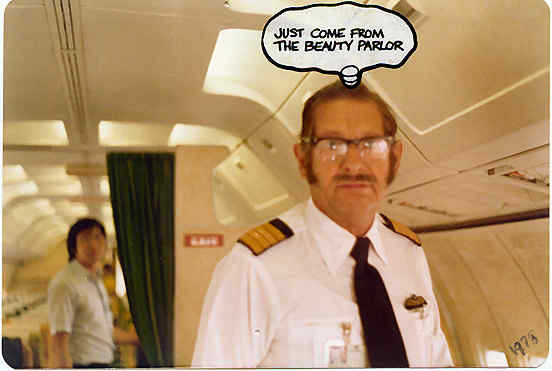

Captain Joe Ziskovsky of Air Nauru in 1977

This is an edited extract of Joe’s adventure, flying the Martin Marauder solo!

“After the war I was assigned to a Naval air transport squadron at Patuxent River for a short time, and then to what is now Cape Canaveral. It used to be Banana River Naval Air Station, which was an assembly base for all the war surplus aircraft in the south east USA, for the Navy. When I arrived, nearly all the people originally stationed there were getting discharged on points for length of service etc.

After being there for only two weeks (there were no tower operators and only one lieutenant and five enlisted pilots), we asked if we could check out in any or all of the planes that were there, and were being brought there. The lieutenant didn't give a damn as he was also awaiting discharge, and so all of us enlisted men would get a handbook and sit in the cockpit for a while, figure out how to start the plane, get the emergency procedures put on a clipboard with the power settings and speeds, and when we got enough guts, would go out and take off.

There were a few hairy moments, especially on landings, as the runway was only 4000 feet long, and on the first flight we wanted to carry a bit more speed on the approach. The worst scare I think I had, was when I decided to check out in what the Navy called the JM-1, which was the Navy version of the Martin Marauder. The Navy used it for towing targets for gunnery practice. Its biggest problem was that all the handbooks were for the Air Force versions, and most of the switches and other stuff like fuel tank valves etc were in a different place.

Anyway, the day I got the guts to go, and not knowing that the Marauder had piss poor expander brakes, I took off solo. The damned aeroplane literally ran away with me. It was not a joke. After levelling out at 10,000 feet, I did a couple of approach to stalls, plus some feathering, steep turns, and finally returned for landing. I spent a long time trying to get the beast on the ground. I had read in the flight manual not to get too slow in the final turn with or without flaps, and not to let the engines load up at idle power.

I am sure I made five or six approaches before I got it on the ground the first time, although it was way down the runway. I decided to make it a touch and go as I was too far down to pull up. After a few more attempts to land I finally got it on the ground pretty fast, and with a bit of luck I managed to run out of runway and out of brakes at the same time!

I nursed it back to the ramp and parked it. There was only one mechanic left on the base, so the next guy took one of the other three remaining Marauders that were parked on the field. Meanwhile I managed to get checked out (sort of), in all twelve different types of aircraft on the base, plus the Martin Mariner PBM seaplane. While you sat up a hell of a lot higher than the Catalina's, it didn't fly or land much differently.

I then got transferred from there to San Diego to a ferry squadron moving airplanes all over the USA to maintenance and overhaul shops, and getting last planes off the assembly lines at the end of the war that had been sitting for a long time. My favourite was the Grumman Tigercat. It was a really easy plane to fly and land but had a lousy hydraulic system and brakes. It had an emergency air bottle to stop the plane if you lost the hydraulic system. The only problem was that even though you could hand pump the gear and flaps down, when you pulled the air bottle to stop, you could only watch as the wheels locked, the tyres would burst and you just hung on. Other than that, it was a real goer, with two Pratt and Whitney R2800 engines and only weighing about 7000lbs in ferry configuration. You could move it out to 400 knots for a thrill, but it would really chew the gas”.

Tony Fisher had just over 200 hours as a private pilot on a Fairchild Argus and a Ryan Trainer before his first solo on a Mustang. By contrast, Joe Ziskovsky was an experienced Navy pilot when he first flew solo on the Martin Marauder; a hot aircraft with a deadly reputation as a widow maker. Both pilots had the fright of their lives but survived to tell their tales. I am glad they did, because those sort of things wouldn’t happen these days…

|

||

|

Because of Covid-19, this will be the first year we're not going to Hawaii. Normally we don't go because we can't afford it. |

||

|

|

||

|

Back Go to page: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Forward |

||

was not much at all and a harsh pull back on the stick at the bottom of

the dive would easily convert the dive into a rocketing climb. Well, all

I can say is that a Wirraway is not a Stuka and it quickly showed George

who was boss.

was not much at all and a harsh pull back on the stick at the bottom of

the dive would easily convert the dive into a rocketing climb. Well, all

I can say is that a Wirraway is not a Stuka and it quickly showed George

who was boss.